In phonetics, vowel reduction is any of various changes in the acoustic quality of vowels as a result of changes in stress, sonority, duration, loudness, articulation, or position in the word (e.g. for the Creek language[1]), and which are perceived as "weakening". It most often makes the vowels shorter as well.

Vowels which have undergone vowel reduction may be called reduced or weak. In contrast, an unreduced vowel may be described as full or strong.

Transcription

| Near- front |

Central | Near- back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Near-close | ᵻ (ɨ) | ᵿ (ɵ) | ||

| Mid | ə | |||

| Near-open | ɐ | |||

There are several ways to distinguish full and reduced vowels in transcription. Some English dictionaries mark full vowels for secondary stress, so that e.g. ⟨ˌɪ⟩ is a full unstressed vowel while ⟨ɪ⟩ is a reduced, unstressed schwi.[lower-alpha 1] Or the vowel quality may be portrayed as distinct, with reduced vowels centralized, such as full ⟨ʊ⟩ vs reduced ⟨ᵿ⟩ or ⟨ɵ⟩. Since the IPA only supplies letters for two reduced vowels, open ⟨ɐ⟩ and mid ⟨ə⟩, transcribers of languages such as RP English and Russian that have more than these two vary in their choice between an imprecise use of IPA letters such as ⟨ɨ⟩ and ⟨ɵ⟩,[lower-alpha 2] or of custom non-IPA (extended IPA) letters such as ⟨ᵻ⟩ and ⟨ᵿ⟩. The French reduced vowel is also rounded, and for a time was written ⟨ᴔ⟩ (turned ⟨œ⟩), but this was not adopted by the IPA and it is now generally written ⟨ə⟩.

Weakening of vowel articulation

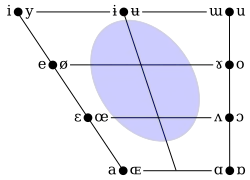

Phonetic reduction most often involves a mid-centralization of the vowel, that is, a reduction in the amount of movement of the tongue in pronouncing the vowel, as with the characteristic change of many unstressed vowels at the ends of English words to something approaching schwa. A well-researched type of reduction is that of the neutralization of acoustic distinctions in unstressed vowels, which occurs in many languages. The most common reduced vowel is schwa.

Whereas full vowels are distinguished by height, backness, and roundness, according to Bolinger (1986), reduced unstressed vowels are largely unconcerned with height or roundness. English /ə/, for example, may range phonetically from mid [ə] to [ɐ] to open [a]; English /ᵻ/ ranges from close [ï], [ɪ̈], [ë], to open-mid [ɛ̈]. The primary distinction is that /ᵻ/ is further front than /ə/, contrasted in the numerous English words ending in unstressed -ia. That is, the jaw, which to a large extent controls vowel height, tends to be relaxed when pronouncing reduced vowels. Similarly, English /ᵿ/ ranges through [ʊ̈] and [ö̜]; although it may be labialized to varying degrees, the lips are relaxed in comparison to /uː/, /oʊ/, or /ɔː/. The primary distinction in words like folio is again one of backness. However, the backness distinction is not as great as that of full vowels; reduced vowels are also centralized, and are sometimes referred to by that term. They may also be called obscure, as there is no one-to-one correspondence between full and reduced vowels.[3]

Sound duration is a common factor in reduction: In fast speech, vowels are reduced due to physical limitations of the articulatory organs, e.g., the tongue cannot move to a prototypical position fast or completely enough to produce a full-quality vowel (compare with clipping). Different languages have different types of vowel reduction, and this is one of the difficulties in language acquisition (see e.g. Non-native pronunciations of English and Anglophone pronunciation of foreign languages). Vowel reduction of second language speakers is a separate study.

Stress-related vowel reduction is a principal factor in the development of Indo-European ablaut, as well as other changes reconstructed by historical linguistics.

Vowel reduction is one of the sources of distinction between a spoken language and its written counterpart. Vernacular and formal speech often have different levels of vowel reduction, and so the term "vowel reduction" is also applied to differences in a language variety with respect to, e.g., the language standard.

Some languages, such as Finnish, Hindi, and classical Spanish, are claimed to lack vowel reduction. Such languages are often called syllable-timed languages.[4] At the other end of the spectrum, Mexican Spanish is characterized by the reduction or loss of the unstressed vowels, mainly when they are in contact with the sound /s/.[5][6] It can be the case that the words pesos, pesas, and peces are pronounced the same: [ˈpesə̥s].

Vowel inventory reduction

In some cases phonetic vowel reduction may contribute to phonemic (phonological) reduction, which means merger of phonemes, induced by indistinguishable pronunciation. This sense of vowel reduction may occur by means other than vowel centralisation, however.

Many Germanic languages, in their early stages, reduced the number of vowels that could occur in unstressed syllables, without (or before) clearly showing centralisation. Proto-Germanic and its early descendant Gothic still allowed more or less the full complement of vowels and diphthongs to appear in unstressed syllables, except notably short /e/, which merged with /i/. In early Old High German and Old Saxon, this had been reduced to five vowels (i, e, a, o, u, some with length distinction), later reduced further to just three short vowels (i/e, a, o/u). In Old Norse, likewise, only three vowels were written in unstressed syllables: a, i and u (their exact phonetic quality is unknown). Old English, meanwhile, distinguished only e, a, and u (again the exact phonetic quality is unknown).

Specific languages

English

Stress is a prominent feature of the English language, both at the level of the word (lexical stress) and at the level of the phrase or sentence (prosodic stress). Absence of stress on a syllable, or on a word in some cases, is frequently associated in English with vowel reduction – many such syllables are pronounced with a centralized vowel (schwa) or with certain other vowels that are described as being "reduced" (or sometimes with a syllabic consonant as the syllable nucleus rather than a vowel). Various phonological analyses exist for these phenomena.

Latin

Old Latin had initial stress, and short vowels in non-initial syllables were frequently reduced. Long vowels were usually not reduced.

Vowels reduced in different ways depending on the phonological environment. For instance, in most cases, they reduced to /i/. Before l pinguis, an /l/ not followed by /i iː l/, they became Old Latin /o/ and Classical Latin /u/. Before /r/ and some consonant clusters, they became /e/.

- fáciō, *ád-faciō > Old Latin fáciō, áfficiō "make, affect"

- fáctos, *ád-factos > fáctos, áffectos "made, affected" (participles)

- sáltō, *én-saltō > Old Latin sáltō, ínsoltō "I jump, I jump on"

- parō, *pe-par-ai > Latin párō, péperī "I give birth, I gave birth"

In Classical Latin, stress changed position and so in some cases, reduced vowels became stressed. Stress moved to the penult if it was heavy or to the antepenult otherwise.

- Classical Latin fáciō, affíciō

- fáctus, afféctus

- sáltō, īnsúltō

Romance languages

Vulgar Latin, represented here as the ancestor of the Italo-Western languages, had seven vowels in stressed syllables (/a, ɛ, e, i, ɔ, o, u/). In unstressed syllables, /ɛ/ merged into /e/ and /ɔ/ merged into /o/, yielding five possible vowels. Some Romance languages, like Italian, maintain this system, while others have made adjustments to the number of vowels permitted in stressed syllables, the number of vowels permitted in unstressed syllables, or both. Some Romance languages, like Spanish, French and Romanian, lack vowel reduction altogether.

Italian

Standard Italian has seven stressed vowels and five unstressed vowels, as in Vulgar Latin. Some regional varieties of the language, influenced by local vernaculars, do not distinguish open and closed e and o even in stressed syllables.

Neapolitan

Neapolitan has seven stressed vowels and only four unstressed vowels, with e and o merging into /ə/. At the end of a word, unstressed a also merges with e and o, reducing the number of vowels permitted in this position to three.

Sicilian

Sicilian has five stressed vowels (/a, ɛ, i, ɔ, u/) and three unstressed vowels, with /ɛ/ merging into /i/ and /ɔ/ merging into /u/. Unlike Neapolitan, Catalan or Portuguese, Sicilian incorporates this vowel reduction into its orthography.

Catalan

Catalan has seven or eight vowels in stressed syllables and three, four or five vowels in unstressed syllables, depending on dialect. The Valencian dialect has five, as in Vulgar Latin. Majorcan merges unstressed /a/ and /e/, and central Catalan further merges unstressed /o/ and /u/.

Portuguese

Portuguese has seven or eight vowels in stressed syllables (/a, ɐ, ɛ, e, i, ɔ, o, u/). The vowels /a/ and /ɐ/, which are not phonemically distinct in all dialects, merge in unstressed syllables. In most cases, unstressed syllables may have one of five vowels (/a, e, i, o, u/), but there is a sometimes unpredictable tendency for /e/ to merge with /i/ and /o/ to merge with /u/. For instance some speakers pronounce the first syllable of dezembro ("December") differently from the first syllable of dezoito ("eighteen"), with the latter being more reduced. There are also instances of /ɛ/ and /ɔ/ being distinguished from /e/ and /o/ in unstressed syllables, especially to avoid ambiguity. The verb pregar ("to nail") is distinct from pregar ("to preach"), and the latter verb was historically spelled prègar to reflect that its unstressed /ɛ/ is not reduced.

Portuguese phonology is further complicated by its variety of dialects, particularly the differences between European Portuguese and Brazilian Portuguese, as well as the differences between the respective dialects of the two varieties.

Slavic languages

Bulgarian

In the Bulgarian language the vowels а [a], ъ [ɤ], о [ɔ] and е [ɛ] can be partially or fully reduced, depending on the dialect, when unstressed to [ɐ], [ɐ], [o] and [ɪ], respectively. The most prevalent is [a] > [ɐ], [ɤ] > [ɐ] and [ɔ] > [o], which, in its partial form, is considered correct in literary speech. The reduction [ɛ] > [ɪ] is prevalent in the eastern dialects of the language and is not considered formally correct.

Russian

There are six vowel phonemes in Standard Russian. Vowels tend to merge when they are unstressed. The vowels /a/ and /o/ have the same unstressed allophones for a number of dialects and reduce to a schwa. Unstressed /e/ may become more central if it does not merge with /i/.

Other types of reduction are phonetic, such as that of the high vowels (/i/ and /u/), which become near-close; этап ('stage') is pronounced [ɪˈtap], and мужчина ('man') is pronounced [mʊˈɕːinə].

Early Slavic languages

Proto-Slavic had two short high vowels known as yers: a short high front vowel, denoted as ĭ or ь, and a short back vowel, denoted as ŭ or ъ. Both vowels underwent reduction and were eventually deleted in certain positions in a word in the early Slavic languages, beginning from the late dialects of Proto-Slavic. The process is known as Havlík's law.

Irish

In general, short vowels in Irish are all reduced to schwa ([ə]) in unstressed syllables, but there are some exceptions. In Munster Irish, if the third syllable of a word is stressed and the preceding two syllables are short, the first of the two unstressed syllables is not reduced to schwa; instead it receives a secondary stress, e.g. spealadóir /ˌsˠpʲal̪ˠəˈd̪ˠoːɾʲ/ ('scythe-man').[7] Also in Munster Irish, an unstressed short vowel is not reduced to schwa if the following syllable contains a stressed /iː/ or /uː/, e.g. ealaí /aˈl̪ˠiː/ ('art'), bailiú /bˠaˈlʲuː/ ('gather').[8] In Ulster Irish, long vowels in unstressed syllables are shortened but are not reduced to schwa, e.g. cailín /ˈkalʲinʲ/ ('girl'), galún /ˈɡalˠunˠ/ ('gallon').[9][10]

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ Acoustic vowel reduction in Creek: Effects of distinctive length and position in the word (pdf)

- ↑ Messum, Piers (2002). "Learning and Teaching Vowels" (PDF). Speak Out! (29): 9–27. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- ↑ Bolinger (1986), p. 347.

- ↑ R. M. Dauer. "Stress-timing and syllable-timing reanalysed". Journal of Phonetics. 11:51–62 (1983).

- ↑ Eleanor Greet Cotton, John M. Sharp (1988) Spanish in the Americas, Volumen 2, pp.154–155, URL

- ↑ Lope Blanch, Juan M. (1972) En torno a las vocales caedizas del español mexicano, pp. 53–73, Estudios sobre el español de México, editorial Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México URL.

- ↑ Ó Cuív 1944:67

- ↑ Ó Cuív 1944:105

- ↑ Ó Dochartaigh 1987:19 ff.

- ↑ Hughes 1994:626–27

Bibliography

- Bolinger, Dwight (1986), Intonation and Its Parts: Melody in Spoken English, Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-1241-7

- Collins, Beverley; Mees, Inger M. (2003) [First published 1981], The Phonetics of English and Dutch (5th ed.), Leiden: Brill Publishers, ISBN 9004103406