| Sound change and alternation |

|---|

| Fortition |

| Dissimilation |

Tone sandhi is a phonological change that occurs in tonal languages. It involves changes to the tones assigned to individual words or morphemes, based on the pronunciation of adjacent words or morphemes. This change typically simplifies a bidirectional tone into a one-directional tone. Tone sandhi is a type of sandhi, which refers to fusional changes, and is derived from the Sanskrit word for "joining."

Languages with tone sandhi

Tone sandhi occurs to some extent in nearly all tonal languages, manifesting itself in different ways.[1] Tonal languages, characterized by their use of pitch to affect meaning, appear all over the world, especially in the Niger-Congo language family of Africa, and the Sino-Tibetan language family of East Asia,[2] as well as other East Asian languages such as Kra-Dai, Vietnamese, and Papuan languages. Tonal languages are also found in many Oto-Manguean and other languages of Central America,[2] as well as in parts of North America (such as Athabaskan in British Columbia, Canada),[3] and Europe.[2]

Many North American and African tonal languages undergo "syntagmatic displacement", as one tone is replaced by another in the event that the new tone is present elsewhere in the adjacent tones. Usually, these processes of assimilation occur from left to right. In some languages of West Africa, for example, an unaccented syllable takes the tone from the closest tone to its left.[4] However, in East and Southeast Asia, "paradigmatic replacement" is a more common form of tone sandhi, as one tone changes to another in a certain environment, whether or not the new tone is already present in the surrounding words or morphemes.[1]

Chinese languages

Many languages spoken in China have tone sandhi; some of it quite complex.[2] Southern Min (Minnan), which includes Hokkien, Taiwanese, and Teochew, has a complex system, with in most cases every syllable changing into a different tone, and which tone it turns into sometimes depending on the final consonant of the syllable that bears it.

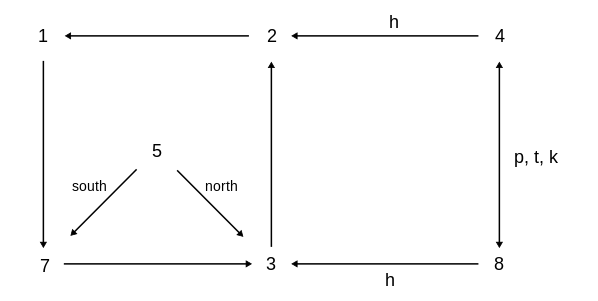

Take for example Taiwanese varieties of Hokkien, which have two tonemes (numbered 4 and 8 in the diagram above) that occur in checked syllables (those ending in a stop consonant) and five tonemes in syllables that do not end in a stop. In Taiwanese, within a phonological phrase, all its non-neutral-tone syllables save for the last undergo tone sandhi. Among the unchecked syllables, tone 1 becomes 7, 7 becomes 3, 3 becomes 2, and 2 becomes 1. Tone 5 becomes 7 or 3, depending on dialect. Stopped syllables ending in ⟨-p⟩, ⟨-t⟩, or ⟨-k⟩ take the opposite tone (phonetically, a high tone becomes low, and a low tone becomes high) whereas syllables ending in a glottal stop (written as ⟨-h⟩ in Pe̍h-ōe-jī) drop their final consonant to become tone 2 or 3.

Tone sandhi in Sinitic languages can be classified with a left-dominant or right-dominant system, depending on whether the leftmost or rightmost item keeps its tone. In a language of the right-dominant system, the right-most syllable of a word retains its citation tone (i.e., the tone in its isolation form). All the other syllables of the word must take their sandhi form. Mandarin Tone 3 Sandhi and Taiwanese Hokkien tone sandhi are both right-dominant.

In a left-dominant system, the leftmost tone tends to spread rightward.[5][6][7]

Shanghainese is an example of a left-dominant system.[8]

Hmong

The seven or eight tones of Hmong demonstrate several instances of tone sandhi. In fact the contested distinction between the seventh and eighth tones surrounds the very issue of tone sandhi (between glottal stop (-m) and low rising (-d) tones). High and high-falling tones (marked by -b and -j in the RPA orthography, respectively) trigger sandhi in subsequent words bearing particular tones. A frequent example can be found in the combination for numbering objects (ordinal number + classifier + noun): ib (one) + tus (classifier) + dev (dog) > ib tug dev (note tone change on the classifier from -s to -g).

What tone sandhi is and what it is not

Tone sandhi is compulsory as long as the environmental conditions that trigger it are met. It is not to be confused with tone changes that are due to derivational or inflectional morphology. For example, in Cantonese, the word "sugar" (糖) is pronounced tòhng (/tʰɔːŋ˨˩/ or /tʰɔːŋ˩/, with a low falling tone, whereas the derived word "candy" (also written 糖) is pronounced tóng (/tʰɔːŋ˧˥/, with mid rising tone. Such a change is not triggered by the phonological environment of the tone, and therefore is not an example of sandhi. Changes of morphemes in Mandarin into their neutral-tone versions are also not examples of tone sandhi.

In Hokkien (again exemplified by Taiwanese varieties), the words kiaⁿ (whose citation tone[lower-alpha 1] is high level and means ‘to be afraid’) plus lâng (whose citation tone is rising and means ‘person, people’) can combine via either of two different tonal treatments with a corresponding difference in resulting meaning. A speaker can pronounce the lâng as a neutral-tone, here phonetically a low tone, which causes the immediately preceding kiaⁿ morpheme to retain its citation tone and thus not undergo tone sandhi. The result means ‘to be frightful’ (written in Pe̍h-ōe-jī as kiaⁿ--lâng).

However, one can instead cause the word to undergo tone sandhi, causing lâng to keep its citation tone, due to being the final non-neutral tone in the phonological phrase, and also causing the kiaⁿ to take its sandhi tone, mid level, due to its coming earlier in the phrase than the last non-neutral-tone syllable. This latter treatment means ‘to be frightfully dirty’ or ‘to be filthy’ (written as kiaⁿ-lâng). The former treatment does not involve the application of the tone sandhi rules, but rather is a derivational process (that is, it derives a new word), while the latter treatment does involve tone sandhi, which applies automatically (here as anywhere that a phrase contains more than one non-neutral tone syllable).

Examples

Mandarin Chinese

Standard Chinese (Standard Mandarin) features several tone sandhi rules:

- When there are two 3rd tones in a row, the first one becomes 2nd tone. E.g. 你好 (nǐ + hǎo > ní hǎo)[2][10]

- The neutral tone is pronounced at different pitches depending on what tone it follows.

- 不 (bù) is 4th tone except when followed by another 4th tone, when it becomes 2nd tone. E.g. 不是 (bù + shì > bú shì )

- 一 (yī) is 1st tone when it represents the ordinal "first". Examples: 第一个 (dìyīgè). It changes when it represents the cardinal number "1", following a pattern of 2nd tone when followed by a 4th tone, and 4th tone when followed by any other tone. Examples: (for changing to the 2nd tone before a 4th tone) 一次 (yī + cì > yí cì ), 一半 (yī + bàn > yí bàn), 一會兒; 一会儿 (yī + huìr > yí huìr); (for changing to the 4th tone before another tone) 一般 (yī + bān > yì bān), 一毛 (yī + máo > yì máo).

Yatzachi Zapotec

Yatzachi Zapotec, an Oto-Manguean language spoken in Mexico, has three tones: high, middle and low. The three tones, along with separate classifications for morpheme categories, contribute to a somewhat more complicated system of tone sandhi than in Mandarin. There are two main rules for Yatzachi Zapotec tone sandhi, which apply in this order:

- (This rule only applies to class B morphemes.) A low tone will change to a mid tone when it precedes either a high or a mid tone: /yèn nājō/ → yēn nājō "neck we say"

- A mid tone will change to a high tone when it is after a low or mid tone, and occurs at the end of a morpheme not preceding a pause: /ẓīs gōlī/ → ẓís gōlī "old stick"[11]

Molinos Mixtec

Molinos Mixtec, another Oto-Manguean language, has a much more complicated system of tone sandhi. The language has three tones (high, mid, or low, or 1, 2, or 3, respectively), and all roots are disyllabic, meaning that there are nine possible combinations of tones for a root or "couplet". The tone combinations are expressed here as a two digit number (high-low is represented as 13). Couplets are also classified into either class A or B, as well as verb or non-verb. A number of specific rules depending on these three factors determine tone change. One example of a rule follows:[12]

"Basic 31 becomes 11 when following any couplet of Class B but does not change after Class A (except that after 32(B') it optionally remains 31"

ža²ʔa² (class B) "chiles" + ži³či¹ (class A) "dry" > ža²ʔa²ži¹či¹ "dry chiles"[12]

Akan

Akan, a Niger-Congo language spoken in Ghana, has two tones: high and low. The low tone is default.[13] In Akan, tones at morpheme boundaries assimilate to each other through tone sandhi, the first tone of the second morpheme changing to match the final tone of the first morpheme.

For example:

- àkókɔ́ + òníní > àkókɔ́óníní "cockerel"

- ǹsóró + m̀má > ǹsóróḿmá "star(s)"[14]

Motivations

Tone sandhi, especially the case of the Taiwanese Hokkien tone circle, often lacks intuitive phonetic explanations. Specifically, sandhi rules may target classes of phones not previously identified as natural, the conditioning environments may be disjoint, or the tone substitutions may occur without any reason. This is because waves of sound change have hidden the original phonetic motivation of the sandhi rule. In the case of Chinese varieties, though, Middle Chinese tones can be used as natural classes for tone sandhi rules in modern varieties, showing that diachronic information needs to be considered to understand tone sandhi.[15] However, phonetic motivations have been identified for specific varieties.[16] The phonetic unnaturalness of many tone sandhi processes have made it difficult for phonologists to express such processes with rules or constraints.[17]

Phonologically, tone sandhi is often an assimilatory or dissimilatory process. Mandarin Tone 3 sandhi, explained above, is an example of an Obligatory Contour Principle effect because it involves two tone 3 syllables next to each other. The first of the two tone 3's becomes a tone 2 to dissimilate from the other syllable.[18]

Transcription

Sinologists sometimes use reversed Chao tone letters to indicate sandhi, with the left-facing letters of the IPA on the left for the underlying tone, and reversed right-facing letters on the right for the realized tone. For example, the Mandarin example of nǐ [ni˨˩˦] + hǎo [xaʊ˨˩˦] > ní hǎo [ni˧˥xaʊ˨˩˦] above would be transcribed:

- [ni˨˩˦꜔꜒xaʊ˨˩˦]

The individual Unicode components of the reversed tone letters are ⟨꜒ ꜓ ꜔ ꜕ ꜖⟩.

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 Gandour, Jackson T. (1978). "The perception of tone". In Fromkin, Victoria A. (ed.). Tone: A Linguistic Survey. New York: Academic Press Inc. pp. 41–72. ISBN 978-0122673504.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Yip, Moira (2002). Tone. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521774451.

- ↑ Pike, Eunice V. (1986). "Tone contrasts in Central Carrier (Athapaskan)". International Journal of American Linguistics. 52 (4): 411–418. doi:10.1086/466032. S2CID 144303196.

- ↑ Wang, William S-Y. (1967). "Phonological features of tone". International Journal of American Linguistics. 33 (2): 93–105. doi:10.1086/464946. JSTOR 1263953. S2CID 144701899.

- ↑ Zhang, Jie (2007-11-23). "A directional asymmetry in Chinese tone sandhi systems". Journal of East Asian Linguistics. 16 (4): 259–302. doi:10.1007/s10831-007-9016-2. ISSN 0925-8558. S2CID 2850414.

- ↑ Rose, Phil (March 2016). "Complexities of tonal realisation in a right-dominant Chinese Wu dialect - disyllabic tone sandhi in a speaker form Wencheng". Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society. 9: 48–80. ISSN 1836-6821.

- ↑ Yue-Hashimoto, Anne O. (1987). "Tone Sandhi across Chinese Dialects". In Chinese Language Society of Hong Kong; Ma, M.; Chan, Y. N.; Lee, K. S. (eds.). Wang Li Memorial Volumes: English Volume. Joint Publishing Co., HK. pp. 445–474. hdl:10722/167241. ISBN 978-962-04-0339-2.

- ↑ Zhu, Xiaonong Sean (2006). A grammar of Shanghai Wu. LINCOM Studies in Asian Linguistics. München: LINCOM EUROPA. ISBN 978-3-89586-900-6.

- ↑ Chen, Matthew Y. (2000). Tone Sandhi : patterns across Chinese dialects. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-511-04053-9. OCLC 56212035.

- ↑ Chen, Matthew (2004). Tone Sandhi: Patterns Across Chinese Dialects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521652723.

- ↑ Schuh, Russell G. (1978). "Tone rules". In Fromkin, Victoria A. (ed.). Tone: A Linguistic Survey. New York: Academic Press Inc. pp. 221–254. ISBN 978-0122673504.

- 1 2 Hunter, Georgia G.; Pike, Eunice V. (2009). "The phonology and tone sandhi of Molinos Mixtec". Linguistics. 7 (47): 24–40. doi:10.1515/ling.1969.7.47.24. S2CID 145642473.

- ↑ Abakah, Emmanuel Nicholas (2005). "Tone rules in Akan". The Journal of West African Languages. 32 (1): 109–134. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ↑ Marfo, Charles Ofosu (2004). "On tone and segmental processes in Akan phrasal words: A prosodic account". Linguistik Online. 18 (1): 93–110. doi:10.13092/lo.18.768. ISSN 1615-3014. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ↑ Chen, Matthew Y. (2000). Tone Sandhi : patterns across Chinese dialects. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-511-04053-9. OCLC 56212035.

- ↑ Rose, Phil (1990-01-01). "Acoustics and Phonology of Complex Tone Sandhi". Phonetica. 47 (1–2): 1–35. doi:10.1159/000261850. ISSN 1423-0321. S2CID 144515303.

- ↑ Zhang, Jie (2014-01-30). "Tone Sandhi". Oxford Bibliographies. doi:10.1093/obo/9780199772810-0160.

- ↑ Yip, Moira (2007-02-01). "Tone". In Lacy, Paul de (ed.). The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 229–252. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511486371.011. ISBN 978-0-511-48637-1.