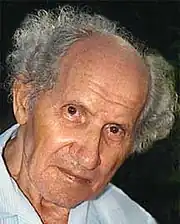

Chaim Goldberg | |

|---|---|

Chaim Goldberg, circa 1995 | |

| Born | Chaim Goldberg March 20, 1917 |

| Died | June 26, 2004 (aged 87) |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Education | Professor Tadeusz Pruszkowski Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, École des Beaux-Arts |

| Known for | Painting, sculpture, engraving |

| Movement | Post-expressionism, Emotivism |

| Spouse | Rachel Goldberg |

| Children | Victor Goldberg, Shalom Goldberg |

| Website | chaimgoldberg |

Chaim Goldberg (March 20, 1917 – June 26, 2004) was a Polish-Israeli-American artist, painter, sculptor, and engraver. He is known for being a chronicler of Jewish life in the eastern European Polish villages (or shtetlekh) like the one in his native Kazimierz Dolny in south-eastern Poland. He witnessed the colorful life, began to draw what he saw as the recurring art colony atmosphere became the highpoint of his self actualization dreams seeing himself become an artist like the ones who visited the village. He yearned to experience life as they did for himself, and later undertook the mission of being a leading painter of Holocaust-era art, which to the artist was seen as an obligation and art with a sense of profound mission.[1]

Following World War II he emigrated to Israel and in 1967 to the United States. He and his family became US citizens in 1973. He died in Boca Raton, Florida, in 2004.

Early life

Goldberg was born in a wooden clapboard house built by his father, a village cobbler. The house stood on Blotna Street as it was called at the time, due to the fact that the creek would overflow and the road turned to a muddy area. As a young boy of 6 he gravitated to creating little figurines carved from stones which he gave away to his friends. Later he took up drawing and painting with basic shoemaker paints that he found at his father's workbench. He was the ninth child and the first boy after eight girls. He grew up in a religious home in Kazimierz Dolny. He would observe and draw the beggars and klezmers who frequented his home as guests. His father would encourage their stays by letting it be known that the humble Goldberg home was open for those who could not pay for their night stay at any of the inns. They were surely welcome there. These characters became Goldberg's early models.[1]

Discovery and first shtetl period

On a crisp day in the fall of 1931, Dr. Saul Silberstein, a student of Sigmund Freud who was doing post-doctorate work on his book, Jewish Village Mannerisms came into the Goldberg cobbler workshop to have his shoes repaired. As he waited for his shoes, he noticed the numerous artworks that were attached to the wall with shoe nails and inquired who the artist was.

Silberstein spent the entire night reviewing the young artist’s work. In the morning, they went by foot to Lublin, a distance of 26 miles, and Dr. Silberstein obtained the opinions of several respected individuals of the work by Goldberg. He then got him several small scholarships based on these letters of recommendation. This helped finance his early education at the "Józef Mehoffer School for Fine Arts", in Kraków, from which he graduated in 1934.

Dr. Silberstein was able to interest several other wealthy sponsors, such as the honorable Felix Kronstein, a judge, and a newspaper publisher who supported the artist through his graduation from the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. At 17, he was the youngest to be admitted and studied under the Rector of the Academy and Professor Tadeusz Pruszkowski, Kowarski, Władysław Skoczylas and Jan Gotard.[1]

The beauty of Kazimierz Dolny had long ago been discovered by artists who had flocked there in large numbers over the years. Between the First World War and the Second World War, Kazimierz Dolny became known as an Art Colony as well. Prof. Tadeusz Pruszkowski had built a summer studio in the mountains and attracted his students to come down and paint outdoors. many of these artists as well as older ones painted the life they saw and the landscape. Goldberg became stimulated by this traffic of artists and began to do art as well. When he was discovered he had not attended any school or private lessons. He watched what the other artists did and was encouraged to do the same; set himself up with a home-made easel and painted outdoors. When he was discovered at the age of 14, his collection included landscapes as well as paintings of the vagabond types that frequented his home as guests.

The war years 1939–1945

Goldberg was conscripted into the Polish army in the fall of 1938. He was assigned to the artillery brigade that guarded Warsaw. After the Polish army surrendered to the Germans, he was taken into custody as a POW (Prisoner of War) and held in a labor camp. He managed to escape and tried to rescue his parents and family, who would not believe that the Germans had any intention of hurting the Jews. He could not motivate them to flee with him.

So Goldberg, his future wife, her sister, and their parents became exiles escaping to Russia on foot. They kept moving north as the German armies advanced and ended up in Novosibirsk. Goldberg married Rachel on April 15, 1944. They were able to return to Poland in 1946.[1]

Paris fellowship and emigration to Israel

Goldberg received a fellowship from the Polish Ministry of Culture to study at the Ecole de Beaux Arts in Paris, and in 1949 they returned to Poland. He worked on various commissions for the Polish Government and, in 1955, made an application to be allowed to immigrate to Israel. Poland was awash with a new Communist regime and Social Realism – that Goldberg found to be distasteful. The regime frowned on depictions of "Jewish Life" in Post-War art which drove a final rift between the artist and his intent to help rebuild the destroyed capital and other cities of Poland. Instead, his wife Rachel and his two sons, Victor and Shalom, had no other choice but to leave Poland and emigrate to Israel.

The Goldberg family arrived in Israel in 1955 and began a new life. They stayed in Israel until 1967. Goldberg exhibited, and Rachel sold his work to American, and Canadian tourists, and Israeli collectors. Despite that Safed (near Tiberias) was the art colony of record, Goldberg's presence in northern Tel Aviv became a well-known bit of art trivia to almost everyone, and his studio drew from the wealthier tourists who frequented Hotel Ramat Aviv.[1]

Discovering Modernism

Pervasive in his watercolors, one can see the ‘stained glass’ look that he developed in 1963. He added the black lines to the color areas as a final step that he did in the studio.

This developed by accident: His son, Shalom, recalls accompanying his father on a painting trip to Tiberias. "He began his outdoor painting session by making his preliminary pencil composition and then splashed the watercolors on the sheet, brushing the color once and orienting it by the areas he sketched out, however, the session was cut short by a sudden rainstorm." Goldberg and his son packed up and returned to the studio with the drying watercolors, being held horizontally, still taped to his boards, and he set them aside on a countertop he had in the studio. "The next morning," his son recalls, "he unpacked a purchase of black magic markers and sat down to try them out on the newly coated watercolors. To his surprise, the black lines became a look he welcomed and which he began to apply to most of his work with water-based paints. Beginning with this accidental interruption, he evolved, progressing quickly, a unique style that found its way into all his other themes, even his abstract work."

Second shtetl period

Once ensconced in his large studio, Goldberg began to create large paintings that depicted Jewish life that he remembered in his Shtetl of Kazimierz Dolny. During this period, of 1960-1966, he created some of his best-known paintings, such as The Wedding (in the collection of the Spertus Museum, Chicago); The Shtetl (in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY);, Simchat Torah (in a private collection, NY); and Don't Forget.

Sculptures

Goldberg's insatiable desire to create art in many mediums knew no end. He engraved and sculpted in wood, stone, and metal. Here we see a 9+1⁄2-foot-tall carving from oak, titled WE. He would stain his sculptures in various tones and have editions of 8 bronzes cast of each one he chose for editioning. His main advisor was his wife of 65 years, Rachel.

The United States

In 1967, Goldberg arrived in the United States, with a two-year business visa on an exhibition tour and continued to paint, and create line engravings of his village characters, as well as sculpt. His subject matter widened while living in New York, which became one of his "themes." He and his family decided to become citizens of the United States in 1973.

Influences

Goldberg's "Culture Shock" series and other series based on real life and politics of the period were the works of the series "Mad Drivers." Some of his work dealt with his own dream sequences, such as the "Violin Thief Sequence" and the "Bird Dream Sequence."

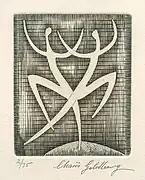

In 1974, Goldberg attended a performance of Emmett Kelly, Jr.'s circus and began a series of drawings and other works on paper inspired by the circus theme. Then dance took center stage as his main subject. He also carved in wood. His body of work on the dance theme included paintings, watercolors, and sculptures carved in wood or made of aggregate concrete. Goldberg continued line engraving and created a suite of 6 engravings titled, "Spring."

In videotaped interviews with the artist's son, Shalom, it becomes clear that Goldberg's career took two parallel paths of creation by virtue of his ability to compartmentalize his time and to the success of his Judaic theme to support him and his family throughout his life.

Spring 1

Spring 1 Spring 2

Spring 2 Spring 3

Spring 3

The dance theme

In 1970 the famous Yiddish Stage Dancer and friend of the artist, Felix Fibich, posed for Goldberg in his home by striking dance positions on a low-standing coffee table in the artist's living room. Goldberg quickly executed numerous pencil drawings while his son, Shalom made BW pictures that he later developed in his darkroom. This reference material gave rise to Goldberg's Dance art work. He made watercolors and oil paintings. When the artist moved to Houston, he began to sculpt dance figures by carving them directly into wood, these were later cast into bronze and issued as small editions of eight. The carvings and his bronzes became very desired and trendy.

The Holocaust theme

In 1942 while in exile in Russia, Goldberg began making an effort to document what he heard. He returned to Poland with his wife and son, Victor, and began to create over 150 works of art dealing with the Holocaust, many of which are in the permanent collection of several museums, namely the Spertus Institute for Jewish Learning and Leadership in Chicago.[1]

The four shtetl periods

The artist’s creative history can be divided into several phases and themes to better understand his push-pull forces. The chart below documents Goldberg’s concurrent themes and thus his push-pull between creating more art for his mission to make Shtetl Life eternalized and his actual need for a Post-War series of themes and methodologies of creating art; all proving that his brand is a more balanced one rather that and intended one for commercialization.

Working on several themes concurrently

Goldberg trained himself in compartmentalizing his various themes by using different areas of his studio at different times of the day. He would go to his painting studio to paint based on a stream of creative time, and then have lunch with his wife, Rachel. After lunch, he would walk into his engraving area and, once seated, was able to forget his other drives or interests and stay focused on engraving, proofing, and so on. This time management system enabled him to work on various themes and mediums concurrently. However, when it came to his painting of the Holocaust theme, he had to "cleanse his head," as he referred to it. It became a well-known fact that he could create watercolors, or paint the Dance theme, for example, during one part of the day and then move on to painting his Shtetl Life recollections. Disciplined and talented, these ran as a dichotomy with Goldberg, a man gifted in numerous media requiring different disciplines.

Emotivism-based contemporary expression

Working concurrently between his traditional Shtetl theme and a bold, new channel that can be identified with a start in 1970 in full force and lasted through the 80s, Goldberg's genius is proven with his hundreds of drawings that reveal his inner thoughts. He responded to modern life around him after a brief shock, and each evening, after dinner, he sat in the kitchen, or his den, and made hundreds of pen and ink drawings that can best be defined, as Emotivism. In his drawings, the artist appears to be assaulted, surrounded, and in contact with a horde of troubled personalities who are seen at times as suffocating him, deafening, confusing, tearing out his head, and at times having him participate in watching over their evil doings, or mere gatherings. He drifts from scene to scene, profoundly in increasing pain by what he witnesses. Life appears to be encroaching upon him, sometimes threatening him, reminding him of wisdom that had been lost or sold, sacrificing the individual’s boundaries and freedoms. The artist responds with an outpouring of pen and ink drawings created as a way to journal his fleeting thoughts. We can see what he had glimpsed.

Art with an Emotivism-based focus or perspective has appeared in the works of such artists as Willem de Kooning, Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Maryan Maryan (a Holocaust survivor), and numerous others who had their own pains to express as well. Even Pablo Picasso, in some of his work, could be considered to have contributed to this wave. In Francis Bacon’s work and a few others, the artists expressed their pains, while their works were mislabeled as Neo-Expressive, a polite or ‘PC’ correct way of saying “a gay artist.” If one takes the time to comprehend the narrative in these paintings accurately and leaves much to the viewer’s subjective interpretation, the emotive content becomes empowered. However, the paintings may not contain clearly defined statements that would label them as works of an Emotivist type.

Using this new modern way of expression, he was able to channel his pains stemming from the unspeakable acts of extermination beyond his earlier preoccupation with making an everlasting art memorial to his village characters. Now, he channeled numerous references that took shape as descending monsters, nightmares, and dreams of loss, feeling as if a descending monster bird ripped his head out of his body and flew off with it. In some of his other works, a violin is stolen while the artist sleeps under a tree.

His oil paintings and pastels surge beyond the original drawings, and in 1975, he began painting a series of oil paintings expressing the different masks humans assume, or "wear" throughout various interactions, and at various times and wear to conceal their true intentions and feeling, deceptively clinging to a game of gaining their agenda. We see numerous acrylic and oil paintings on wood panels whose narrative is intertwined and a puzzle to uncover. Goldberg's masks and street violence paintings reveal a mind that Could leap from his mission to respond to modernity and its various convoluted aspects.

In 1973 he created a series of mask pen-and-inks depicting a monster regime, (Communism) that wore deceptive masks. Clearly, there is a modern narrative in his creations that demands further study and analysis by art historians.

Other works in this group are Crazy Drivers and The Modern City.

In his Pipelines oil painting, the artist imagines a tube-like channel, like a pipeline that zips the population in and out of the city. This painting and many others in this group were conceived and painted in the early 70s; over fifty years before Elon Musk and his Boring Company.

In other paintings from this period, the artist presents a sense of romantic longing. Perhaps he recalls an unrequited love. One can see many pen-and-inks having an even more sexual or lustful presence and narrative. Intense and profound, yet the art originated with the same man who had committed himself to make a memorial to an earlier way of life... in his Shtetl, Kazimierz Dolny. Now, he presents mature subject matter that is at its heart hidden desires.

Creating dance and abstract As "cleansing forces" from painting the depressing Holocaust

Most artists become satisfied with achieving success with one or two themes, they stop experimenting. Instead, they develop a commercial presence that runs throughout their productive years, exhibiting and showing aspects of their evolution through a more likely color palate that will sell and fetch better pricing. Artists like Chagall, for example, stayed their course and did not Segway into the world of Abstract Expressionism, as if adhering to his established brand. Goldberg, on the other hand was at heart a modernist artist who took a mission upon himself to create a memorial to the life of the Shtetl while experiencing a strange pull to create other themes that did not adhere to the Shtetl brand. He experimented with this as a "cleansing," as he called it, starting in Israel as early as 1964. He returned to the world of Abstract Expressionism later as well and concurrently created sculptures and engravings. He danced right into shapes he called upon and carved them out of wood, chiseled them out of white and pink marble. His sculptures demonstrate a true talent that had a huge range of materials.

Major early exhibitions

In 1971, barely 4 years since his arrival from Israel, the esteemed Catholic college in Queens, New York, St. John's University, hosted an exhibit at their DeAndries Exhibit Hall. Goldberg's major canvas, The Shtetl, which he painted in 1962, was selected by the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Mr. Thomas Hoving, an attending guest at the opening, to be included in the MET's 20th Century Permanent Art Collection – A major achievement and recognition for a foreign-born artist who was not a citizen at the time.

In 1973, still not an American citizen, Goldberg was invited to exhibit his engravings, drawings, watercolors and oil paintings at the Smithsonian Institution's Hall of Graphic Arts, recognizing his exceptional engraving talents and the works he created in the short time period of five years since landing on the American shores. Goldberg and his family were finally made American citizens.

In 1997, Goldberg's work went on exhibit at the Rosen Museum of Art, Boca Raton, (on the campus of the JCC).

Recent major exhibitions

In 2013 the Nadwishlanski Museum in Kazimierz Dolny, Poland, celebrated its Jubilee and the opening of a major museum building with a One Man Show of their own town's now-famous artist – Goldberg. The exhibit opened on December 9, 2013, and closed on August 30, 2014.

In 2016 – The artist's Shtetl Life work was exhibited at 'Museum, I Remember' in Krakow, Poland, from March 20 to July 26, 2016.

In 2016 – The third leg of exhibits in Poland, the exhibit now titled, I Remember the Shtetl opened at the Krakow Palace of Art on September 15 and closed on November 20, 2016.

Final years

In 1987, while working on the modernist themes above, Goldberg returned to painting his beloved Kazimierz Dolny and the Jewish life in the village. This time his paintings were less lyrical and surreal, and instead were more 'story-telling' and documentary. After completing some fifty large canvases in 1997, at the age of 80, he was diagnosed with a disabling illness. He died on June 26, 2004, in Boca Raton, Florida, aged 87.

Exhibitions

- 1931 – "Polish Landscapes," Group Show, Kazimierz-Dolny, Poland

- 1934 – Studio Show, Kazmierz-Dolny, Poland

- 1936 – National Group Show, Warsaw, Poland

- 1937 – National Group Show, Warsaw, Poland (the artist, his future wife and her family were refugees in Siberia)

- 1946 – "Poland After World War II" solo show, Shtczechin, Poland

- 1947 – National Group Show, Warsaw, Poland

- 1949 – National Group Show, Warsaw, Poland

- 1950 – National Group Show, Warsaw, Poland

- 1951 – National Group Show, Warsaw, Poland

- 1952 – National Group Show, Warsaw, Poland

- 1965 – One Man Show, Pioneer House, Giv'atayim, Israel

- 1966 – Retrospective Show, Museum Yad Labanim, Petach Tikvah, Israel (attended by Mrs. Golda Meir – Prime Minister; and Kadish Luz – Speaker of the House (Knesset)

- 1967 – One Man Show, LYS Gallery, New York

- 1968 – One Man Show, Theodor Hertzl Institute, New York City, New York

- 1968 – One Man Show, Mixed Media Art Center, Syracuse, New York

- 1969 – One Man Show, Paul Kessler Art Gallery, Provincetown, Massachusetts

- 1970 – One Man Show, Paul Kessler Art Gallery, Provincetown, Massachusetts

- 1971 – Large Retrospective Exhibit at the DeAndries Gallery, St' John's University, Queens, New York

- 1972 – One Man Show, Mixed Media, Lincoln Mall Art Center, Miami, Florida

- 1972 – Group Show, Mixed Media, American Congress, Washington, D.C.

- 1973 – One Man Show, "Chaim Goldberg's Shtetl" (drawings, watercolors, sculptures, oil paintings and line engravings) Smithsonian Institution, Hall of Graphic Arts, Washington, D. C.

- 1973 – Group Exhibit, "Jewish Motifs and Culture of the 20th Century," Klingspor Museum, Offenbach, Germany

- 1974 – One Man Show, The Avila Art Center, Jewish Synagogue, Caracas, Venezuela

- 1977 – Group Show with the Texas Society of Sculptors, Houston Public Library, Main Branch, Houston, Texas

- 1979 – One Man Show, Museum of Printing History, Houston, Texas

- 1982 – Group Exhibit, "Art of the Twentieth Century – A Revelation," Congregation Beth Israel, Houston, Texas

- 1985 – Group Exhibit, "Twenty-Sixth Invitational," Longview Museum of Art, Longview, Texas

- 1994 – Group Exhibit, "Shtetl Life," the Nathan and Faye Hurvitz Collection, the Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life, Berkeley, California Goldberg's "Marketplace", a hand-colored litho was on the cover of the exhibit catalog.

- 1997 – One Man Exhibit, "Chaim Goldberg at 80," Nathan B. Rosen Museum, Adolph & Rose Levis Jewish Community Center, Boca Raton, Florida

- 1997 – One Man Exhibit, "Remembering the Shtetl – 75 Years of the Art of Chaim Goldberg," Texas Union Art gallery, University of Texas at Austin

- 2002 – One Man Exhibit, "Oil Paintings of the Shtetl," Shir Art Gallery, Southfield, Michigan

- 2003 – One Man Exhibit, "Landscapes and Observations," Shir Art Gallery, Southfield, Michigan

- 2004 – One Man Exhibit, "Engravings and Lithos," Shir Art Gallery, Southfield, Michigan

- 2009 – Group Exhibition, "Jewish Interwar Painters of Kazimierz Dolny," Poland, Rapperswil Castle by Lake Zurich, Switzerland

- 2009 – One Man Exhibit "Remembering the Shtetl," JRM Artists' Space, National Bottle Museum, Ballston Spa, New York

- 2013 – One Man Show of over 160 drawings, watercolors, and oil paintings from 1946 to 2000, "Chaim Goldberg Returns to Kazimierz Dolny," from 09.12.2013 to 31.08.2014 Muzeum Nadwiślański, Kazimierz Dolny, Poland

- 2015 – One Man Show of drawings and paintings KAMIENICA CELEJOWSKA / 11 grudnia 2015 – 3 kwietnia 2016 Muzeum Nadwiślański, Kazimierz Dolny, Poland

- 2016 – One Man Show of 75 drawings, watercolors, and paintings Museum, I Remember, Kraków, Poland / May 8 – July 28

- 2016 – One Man Show "I Remember The Shtetl" of 100 themed oil paintings, watercolors, drawings, plus 30 of his graphics; works in such mediums as engravings, etchings, and wood engravings, at the Palace of Art in Kraków, September 15 – October 9

Collections

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, 20th Century Permanent Art Collection, New York City, New York

- Museum of Modern Art, New York City, New York

- Beit HaNassi, Jerusalem, Israel

- Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, Israel

- Jerusalem Municipality, Jerusalem, Israel

- Museum Yad Labanim, Petach Tikvah, Israel

- Musée du Petit Palais, Geneva, Switzerland

- National Museum, Warsaw, Poland

- Jewish Museum, Warsaw, Poland

- Klingspor Museum, Offenbach, Germany

- National Gallery of Art, Lessing Rosenwald Collection[2] Washington, D.C.

- National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

- Smithsonian Institution, American Art Museum and Renwick Gallery Collection, Washington, D.C.

- Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Lowe Art Museum, Miami, Florida

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts

- Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut

- Sylvia Plotkin Judaica Museum,[3] Phoenix, Arizona

- Public Library Art Collection, San Francisco, California

- New York Public Library, New York City, New York

- Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut

- Springfield Museum of Art, Springfield, Massachusetts

- Museum of Fine Arts Houston, Houston, Texas

- Houston Public Library, Houston, Texas

- Spertus Institute for Jewish Learning and Leadership, Chicago, Illinois

- Judah L. Magnes Museum, Berkeley, California

- Skirball Museum, Los Angeles, California

- Yeshiva University Museum, New York City, New York

- YIVO, New York City, New York

- Jewish Theological Seminary, Cincinnati, Ohio

- Derfner Judaica Museum, in the Jacob Reingold Pavilion, Riverdale, NY

- POLIN, Warsaw, Poland

- Muzeum Nadwiślański, Kazimierz Dolny, Poland

List of Kazimierz-Dolny artists

The artists who frequented the Kazimierz-Dolny Art Colony were many, some of the Jewish artists were:

- Maurycy (Mosze) Applebaum (1886-1931)

- Eugeniusz Act (1899-1974)

- Jozef Badower (1910-1941)

- Henryk (Henoch) Barcinski (1896-1939)

- Adolph Behrman (1876-1942)

- Henryk Berlewi (1894-1967)

- Salomon (Szulim) Bialogorski (1900-1942)

- Arnold Blaufuks (1894-1943)

- Sasza (Szaje) Blonder (1909-1949)

- Icchak Wincenty Brauner (1887-1944)

- Aniela Cukier (1900-1944)

- Bencion Cukierman (1890-1944)

- Samuel Cygler (1898-1943)

- Herszel Cyna (1911-1942)

- Henryk (Chaim) Cytryn (1911-1943)

- Jakub Cytryn (1909-1943)

- Rachel Diament (1920-2003)

- Boas Dulman (1900-1942)

- Samuel Finkelstein (1890-1943)

- Abraham Frydman (1906-1941)

- Feliks Frydman (1897-1942)

- Jozef Mojzesz Gabowicz (1862-1939)

- Izydor Goldhuber-Czaj (1896-1942)

- Dawid (Dionizy) Grieffenberg (1909-1942)

- Michal Grusz (1911-1943)

- Izaak Grycendler (1908-1944)

- Chaim Hanft (1899-1951)

- Adam Herszaft (1886-1942)

- Elzbieta Hirszberzanka (1899-1942)

- Ignacy Hirszfang (1903-1943)

- Gizela Hufnagel (1903-1997)

- Marcin Kitz (1891-1943)

- Natan Korzen (1895-1941)

- Jozef Kowner (1895-1967)

- Szymon Kratka (1884-1960)

- Izaak Krzeczanowski (1910-1941)

- Chaim Lajzer (1893-1942)

- Natalia Landau (1907-1943)

- Henryk Lewensztadt (1893-1962)

- Mary Litauer (Schneiderowa) (1900-1942)

- Jozef Majzels (1911-1943)

- Arieh Merzer (1910–1974)

- Stella Amelia Miller (1910- ? )

- Maurycy Minkowski (1881-1930)

- Abraham Neuman (1873-1942)

- Szlomo Nussbaum (1906-1946)

- Abraham Ostrzega (1889-1942)

- Samuel Puterman (1901-1955)

- Henryk Rabinowicz (1890-1942)

- Stanislawa Reicher (1889-1943)

- Bernard Rolnicki (1885-1942)

- Roman Rozental (1897-1962)

- Mojzesz Rynecki (1885-1942)

- The Seidenbeutel brothers:

- Efraiim Seidenbeutel (1902-1945)

- Jozef Seidenbeutel (1894-1923)

- Menashe Seidenbeutel (1902-1945)

- Efraiim & Gela Seksztajn(1907-1943)

- Marcel Słodki (1892-1943)

- Arieh Sperski (1902-1943)

- Marek Szapiro (1884-1942)

- Natan Spigel (1900-1942)

- Jozef Tom (1886-1962)

- Feliks Topolski (1907-1989)

- Symcha Trachtner (1893-1942)

- Maurycy Trębacz (1861-1941)

- Tadeusz Trebacz (1910-1945)

- Izrael Tykocinski (1895-1942)

- Jakub Weinles (1870-1938)

- Wladyslaw Weintraub (Chaim Wof) (1891-1942)

- Israel Szmuel (Szmul) Wodnicki (1901-1971)

- Pinkus Zelman (1907-1936)

- Izaak Zajdler (1905-1943)

- Leon Zysberg (1901-1942)

- Fiszel Zylberberg (1909-1942).

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 The National Bottle Museum (2009). "Chaim Goldberg". REMEMBERING THE SHTETL. The National Bottle Museum, Ballston Spa, NY. Archived from the original on 2013-05-02. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- ↑ "The Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection (Selected Special Collections: Rare Book and Special Collections, Library of Congress)". Library of Congress.

- ↑ Karen Polen. "The Plotkin Judaica Museum".

References and sources (books and exhibit catalogs)

- Łukasz Grzejszczak. "Bezpieczna przystań artysty" (available with subscription or purchase). Abraham Adolf Behrman (1876-1942). Stowarzyszenie Historyków Sztuki. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- Darmon, Adrian Around Jewish Art: A Dictionary of Painters, Sculptors and Photographers, Carnot Press, April 2004, ISBN 1592090427

- Brody, Moskowitz-, Cynthia -Bittersweet Legacy, Creative Responses to the Holocaust, University Press of America, Inc. Lanham, Maryland 20706 (Pages 268-269)

- Dr. Waldemar Odorowski; Dorota Święcicka-Odorowska; Dorota Seweryn-Puchalska; Stanisław Święcicki; Jarosław Moździoch, In Kazimierz the Vistula River spoke to them in Yiddish, Published by the Muzeum Nadwiślańskie, Kazimierz Dolny, Poland, 2007.

- Del Calzo, Nick, Rockford, Renee, Raper J., Linda – The Triumphant Spirit, published by the Triumphant Spirit Foundation, 1997. ISBN 0965526003

- Helzel Florence, B., Shtetl life: the Nathan and Faye Hurvitz Collection, Judah L. Magnes Museum, 1993

- Queens Council for the Arts, Chaim Goldberg: Israeli Artist, 1971

- Goldberg, Shalom, Chaim Goldberg: My Shtetl Kazimierz Dolny, SHIR Press, 2007

- Harris, Elizabeth, Chaim Goldberg's Shtetl, exhibit catalog published by the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., 1973.

- Lubieniecki, Krzysztof, Polish Engravers, by General Books LLC, 1983

- Chaim Goldberg. Powrót do Kazimierza nad Wisłą / Chaim Goldberg. Kazimierz Revisited. Editor and Contributor Dr. Waldemar Odorowski, published by Muzeum Nadwiślańskie w Kazimierzu Dolnym – December, 2013 ISBN 9788360736418

Brief description of the publication by the Museum: " Katalog wystawy o tym samym tytule, która prezentowana jest w nowej siedzibie Muzeum Nadwiślańskiego w Kazimierzy Dolnym. Wydawnictwo prezentuje życie i twórczość Chaima Goldberga, który urodził się w Kazimierzu w 1917 roku w biednej rodzinie tutejszego szewca. Dzięki odkryciu jego talentu przez dr. Saula Silbersteina i udzieleniu wsparcia finansowego młody artysta miał szansę studiować w prywatnej Szkole L. Mehofferowej w Krakowie, a nastepnie w Akademii Sztuk Pięknych w Warszawie. Tutaj trafił pod skrzydła prof. Tadeusza Pruszkowskiego, który był nota bene twórcą kazimierskiej kolonii artystycznej. Los sprawił, że Chaim po ucieczce przed Zagładą nigdy do Kazimierza już nie wrócił, ale miasteczko ciągle było obecne w jego twórczości. Obrazy kronikarza kazimierskiego sztetla pokazują zarówno życie codzienne jego mieszkańców, jak i dni świąteczne. To niezwykła opowieść o świecie, który odszedł na zawsze. Katalog wzbogacają eseje specjalistów, w tym syna artysty Shaloma Goldberga."

Bibliography of articles

- Aloisio, Julie, "Chaim Goldberg's Art Celebrates Life," The Villager, 1988, Miami, Florida

- Alyagon, Ofra, "Chaim Goldberg The Artist," (Life and Problems, July 1966, Paris, France

- Amazallag, Giselle, "A Visit with the Artist Chaim Goldberg," Dimensions Magazine, February/March 1997, Boca Raton, Florida

- Avidar, Tamar, "Chaim Goldberg Does Not Forget," (Davar Hashavua, 1965, Tel Aviv, Israel

- Chir, Myriam, "Chaim Goldberg – Painter and Sculptor," (L'information D'Israel, Feb. 1965, Tel Aviv, Israel

- Diamonstein, Barbara, "Chaim Goldberg – From Exile to Genius," Art & Antiques Magazine, June, 2002, US

- Dolbin, B.F., "Chaim Goldberg – The Sholom Aleichem of the Arts," Autlan, July, 1967, New York, NY

- Dluznowski-Dunow, M., "Important Exhibit of Chaim Goldberg," The Forward, 1967, New York, NY

- Dluznowski-Dunow, M., "The Painter and Sculptor Chaim Goldberg," Culture and Life, Polish language publication, 1967, New York, NY.

- Evremond-Saint, "Chaim Goldberg," Le Courier des Arts, June 29, 1967, New York, NY

- Frank, M., "Chaim Goldberg in the Smithsonian National Museum," The Forward, April, 1973, New York, NY

- Friedman, Sousanna, "A Visit with Chaim Goldberg," The Bulletin – American Jewish Libraries, 1978

- Kantz, Shimon, "The Artist Chaim Goldberg," Yiddishe Shriftin, Oct., 1954, Warsaw, Poland

- Hall, D., "Goldberg at the Caravan," Park East Nov. 1st, 1973, New York, NY

- Kiel, C., "The Dynamic Jewish Artist Chaim Goldberg," The Forward, 1987, New York, NY

- Luden, Itzchak, "Chaim Goldberg in the Smithsonian National Museum," The Forward, April 1973, New York, NY

- Massney, P., "Proud Moment," The Long Island Press, March 31, 1971, NY

- Paris, J., "Chaim Goldberg to Exhibit Art," The Long Island Press, March 28, 1971, NY

- Paris, J., "Exhibit Aides Council Reach a Goal," The Long Island Press, April 5, 1971, NY

- Robak, Kazimierz, "I Left My Heart There," Gazeta Antykwaryczna, Part 1 of 3, October 2000, Kraków, Poland

- Robak, Kazimierz, "I Left My Heart There," Gazeta Antykwaryczna, Part 2 of 3, November 2000, Kraków, Poland

- Robak, Kazimierz, "I Left My Heart There," Gazeta Antykwaryczna, Part 3 of 3, December 2000, Kraków, Poland

- Robak, Kazimierz, "Kuzmir in Chaim Goldberg’s painting," Spotkania z Zabytkami, Vol. 3 (253), March 2008. 12-15. Warsaw, Poland

- Rogers, M., "Goldberg Pursues New Directions," Houston Chronicle, Oct. 12th, 1977, Houston, TX

- Samuels, J., "An Artist and His Wife," (Jewish Herald-Voice, March, 1978, Houston, TX)

- Samsot-Hawk, Kathleen, "Chaim Goldberg," (Art Voices, November/December 1977)

- Scott, Paul, "Chaim Goldberg: An Artist Reborn," (Southwest Art Magazine, July/August 1975, Houston, TX)

- Shirey, david, "Chaim Goldberg's Art Shown in Queens," (New York Times, March, 19th 1971, NY)

- Shmulevitz, I., "The Exhibit of the Artist Chaim Goldberg," (The Forward, March 13, 1971, NY)

- Shneiderman, Emil, "The Art of Chaim Goldberg," (The Day Journal, July 2, 1967, New York, NY)

- Shneiderman, Emil, "Chaim Goldberg's Art on Exhibit in Queens," (The Day Journal, March 14, 1971, New York, NY)

- Staingart, T., "An Exhibition of Paintings by Chaim Goldberg," (The Forward, 1967, New York, NY)

- Taube, H., "The Lost World Recaptured in Art," (The Baltimore Jewish Times, April 1973, Baltimore, MD)

- Tennenbaum, Shea, "Chaim Goldberg, The Artist From Kazimierz-Dolny," (The Voice, October 10, 1967, New York, NY)

- Tennenbaum, Shea, "Chaim Goldberg's Jews Live Forever," (The Voice, October 1967, Paris, France)

- The Forward, "Chaim Goldberg's Art Exhibited at the Hertzel Institute," (The Forward, April 12, 1968, New York, NY)

- The Forward, "Leivik House in Tel Aviv Receives Gift from Acknowledged Artist Chaim Goldberg," (The Forward, April 12, 1970, New York, NY)

- The Buffalo Jewish Review, "The Artist Goldberg Exhibits," (December 6, 1970, Buffalo, NY)

- The Houston Chronicle, "Central Library to Unveil A New Goldberg Sculpture," (October 31, 1980, Houston, TX)

- Waisman, Gavriel, "The Artist Chaim Goldberg," (The Day, May 1966, Tel Aviv, Israel)

- Waisman, Gavriel, "The Artist Chaim Goldberg," (Life and Problems, July 1966, Paris, France)

- Zonshain, Jacob, "The Prolific Artist," (Folkshtime, November 15, 1949, Warsaw Poland)

Catalogues Raisonné Series

Vol. #1 – Chaim Goldberg’s Shtetl: The Drawings, series name: The Complete Works of Chaim Goldberg, by Shalom Goldberg, Bayglow Press, January 2015, ISBN 978-1505731392

Vol. #9 – Chaim Goldberg’s Dance, series name: The Complete Works of Chaim Goldberg, by Shalom Goldberg, Bayglow Press, January 2015

Vol. #10 – Chaim Goldberg’s Israeli Landscapes, series name: The Complete Works of Chaim Goldberg, by Shalom Goldberg, Bayglow Press, December 2014, ISBN 978-1503121034

Vol. #11 – Chaim Goldberg’s American Landscapes and Florals, series name: The Complete Works of Chaim Goldberg, by Shalom Goldberg, Bayglow Press, December 2014, ISBN 978-1505438017

Illustrated books

- Friedlander, Albert, Out of the Whirlwind, UAHC Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8074-0703-8

- Roseman, Kenneth, "Until the Messiah Comes", Do It Yourself Jewish Adventure Series, ISBN 0-8074-0706-2 – Front cover illustration, detail from his painting titled, Marketplace.

- Shnayderman, Shemu’el-Leyb, The River Remembers, AAH Publishers, 1970, OCLC Number: 19302464, Translated into English as The River Remembers, (New York : Horizon Press, 1978

Limited-edition portfolios

- "Chaim Goldberg's Shtetl", a portfolio of 10 engravings and intaglio prints (mixed media of etching and some engraving) created earlier as separate editions, published in 1973 to commemorate Goldberg's One Man Show at the Smithsonian's newly inaugurated Hall of Graphic Arts. Portfolio was published by Shalom Goldberg, the artist's son. It consists of the ten works of art held by a double, folded sheet of same Arches paper, and protective glassine sheet, and two original drawings. The edition size was 10 portfolios with ten impressions each. Each impression was printed by had, by the artist in his New York studio in Queens, using a Rembrandt Etching press. The impressions are done in a variety of ink colors, ranging from Lamp Black, to Cerrulian Blue mixed with Prussian Blue and a variety of Sepia shades. Each edition from which the ten identically numbered sets were pulled, were executed in editions of 200 signed and numbered impressions, thus making the portfolio extremely rare. On top of the rarity by the small set of 10, each portfolio cover sheet includes two original illustrations in pen and ink by Goldberg.

Included in each portfolio set are the following works:

- Dreamer – Line Engraving

- To the Unknown – Intaglio

- The Blacksmith – Intaglio

- Moving Day – Intaglio

- Two Hasidic Dancers – Etching

- Seven Hasidic Dancers – Etching

- The Cheder – Intaglio

- Duet – Intaglio

- Purim – Intaglio

- The Hora – Intaglio

Further reading

- The official website of the artist Chaim Goldberg

- Book, "Polish Engravers: Chaim Goldberg, Zofia Albinowska-Minkiewiczowa, Czes?aw S?ania, Raphaėl Kleweta, Józef Hecht, Krzysztof Lubieniecki, published by General Books LLC, 1983

- "The River Remembers, by S. L. Shneiderman, AAH Publishers, 1970, ISBN 978-0818008214

- Shtetl life: The Nathan and Faye Hurvitz Collection, by Florence B. Helzel (Author), Essay by Steven J. Zipperstein, Ph.D., published by Judah L. Magnes Museum (1993), ISBN 978-0943376592

- Bittersweet Legacy, Creative Responses to the Holocaust, Brody, Moskowitz, Cynthia, University Press of America, Inc. Lanham, Maryland 20706 ISBN 978-0761819769

- The Triumphant Spirit: Portraits & Stories of Holocaust Survivors Their Messages of Hope & Compassion by Renee Rockford(Author, Editor), Nick Del Calzo (Editor), Linda J. Raper (Editor) ISBN 978-0965526012

- Book: Out of the Whirlwind, by Friedlander, Albert, UAHC Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8074-0703-8

- Book: In Kazimierz the Vistula River spoke to them in Yiddish...: Jewish painters in the art colony of Kazimierz Dolny, by Dr. Waldemar Odorowski (Author and Editor), published by Muzeum Nadwislanskie, Kazimierz Dolny, Poland 2008

- Book, Chaim Goldberg-Powrót do Kazimierza nad Wisłą / Chaim Goldberg’s Return to Kazimierz, Editor and Contributor Dr. Waldemar Odorowski, published by Muzeum Nadwiślańskie w Kazimierzu Dolnym – December, 2013 ISBN 9788360736418

- Book: Bezpieczna przystań artysty, by Łukasz Grzejszczak. (available with subscription or purchase). Abraham Adolf Behrman (1876-1942). Stowarzyszenie Historyków Sztuki. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- Book: Around Jewish Art: A Dictionary of Painters, Sculptors and Photographers, by Darmon, Adrian, Carnot Press, April 2004, ISBN 1592090427

- Book: Modernism in 6 Mediums:...: The Unknown Art of Chaim Goldberg (Artist Discovery Series), by Shalom Goldberg (Author and Editor), published by Amazon KDP, Clearwater, Florida Dec. 2, 2018

- Book: Chaim Goldberg: Master Engraver... A Catalogue of available graphic work executed between 1960-2000, by Shalom Goldberg (Author and Editor), published by Amazon KDP, Clearwater, Florida June. 9, 2015

- Book: Chaim Goldberg:... A Modernist Artist With a Mission, An Introduction to a Life's Work Part 1 & 2 by Shalom Goldberg (Author and Editor), published by Amazon KDP, Clearwater, Florida May 30, 2015

- Book: Modernist Themes, A Catalogue of Varied Modernist Themes by Shalom Goldberg (Author and Editor), published by Amazon KDP, Clearwater, Florida March 22, 2018

- Book: Chaim Goldberg: The Echoes Never Stop by Shalom Goldberg (Author and Editor), published by Amazon KDP, Clearwater, Florida January 23, 2019

- Book: Chaim Goldberg: Exploring Modernism Vol 5 by Shalom Goldberg (Author and Editor), published by Amazon KDP, Clearwater, Florida November 16, 2018

- Book: Chaim Goldberg: Exploring Modernism Vol 3 by Shalom Goldberg (Author and Editor), published by Amazon KDP, Clearwater, Florida October 30, 2018

- Book: Chaim Goldberg: I Remember the Shtetl by Shalom Goldberg (Author and Editor), published by Alois Rostek, Krakow, Poland January 1, 2016 ISBN 978-8394602703

References

- Article, New York Times, by David Shirey, March 19, 1971 Art & Reviews Sect. Page 28

- Book: Out of the Whirlwind, by Friedlander, Albert, COVER: by Chaim Goldberg UAHC Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8074-0703-8

External links

- Official website dedicated to Chaim Goldberg

- In the Smithsonian Archive

- A visit to an exhibit at a Saratoga Springs, NY museum on YouTube

- Exhibition titled Chaim Goldberg Returns to Kazimierz Dolny, Muzeum Nadwishlanskie December 9, 2013, to August 31, 2014.