| Characters and Caricaturas | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | William Hogarth |

| Year | 1743 |

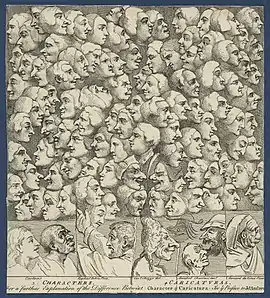

Characters and Caricaturas is an engraving by English artist William Hogarth that he produced as the subscription ticket for his 1743 series of prints, Marriage à-la-mode, and which was eventually issued as a print in its own right. Critics had sometimes dismissed the exaggerated features of Hogarth's characters as caricature and, by way of an answer, he produced this picture filled with characterisations accompanied by a simple illustration of the difference between characterisation and caricature.

Picture

Hogarth's earlier pictures had come under fire from critics for portraying characters in an exaggerated fashion, by reflecting their morality directly in their features, clothes and surroundings. In his book on art, The Analysis of Beauty, Hogarth claimed that the critics had branded all his women as harlots and all his men as caricatures, and complained:

…the whole nest of Phizmongers were upon my back every one of whome has his friends and were all taught to run em down.[1]

To rectify what he saw as an egregious mistake on the part of his critics, and being "perpetually plagued, from the mistakes made among the illiterate, by the similitude in the sound of the words character and caricatura",[2] he designed the subscription ticket for Marriage à-la-mode to clearly illustrate their error. Untitled at the time of issue, it is now known as Characters and Caricaturas or just Characters Caricaturas. At the foot of the picture, Hogarth illustrated the difference between characterisation and caricature by reproducing three character figures from the works of Raphael, and four caricatures: Due Filosofi from Annibale Carracci; a head originally by Pier Leone Ghezzi, but here copied from Arthur Pond's Caricatures; and a Leonardo da Vinci grotesque reproduced from the French Têtes de Charactêres.[3] The images from Raphael are easy to identify as being from his Cartoons (even if they were not labelled Cartons Urbin Raphael Pinx below) but John Ireland commented that the originals' "grandeur, elevation and simplicity are totally evaporated" in Hogarth's rendering.[4] Hogarth also added a line drawing in the space above the second caricature to indicate the simplicity with which caricatures can be produced. Above this demonstration, he filled the remaining space with 100 profiles of "characters", which clearly shows his work has more in common with the work of Raphael than the caricatures produced by the other Italian artists. Hogarth later wrote that he was careful to vary the features of these heads at random to prevent any of the portraits from being identified as a real individual, but the sheer number of profiles inevitably meant this was not entirely successful, since "a general character will always bear some resemblance to a particular one".[2]

Though Hogarth claimed in the inscription to The Bench that "there are hardly any two things more different" than character and caricature, modern commentators suggest that his division of the category of comic portraiture, if not artificial, was at least innovative: Hogarth invented the categories merely to be able to place himself in a line of artistic succession that descended from Raphael and to distance himself from the caricaturists of his day—such as Arthur Pond—who, despite lacking artistic training, were tackling much the same subject matter that Hogarth was himself addressing.[5]

Below the picture, Hogarth added a rider: "For a further Explanation of the Difference Betwixt Character & Caricature See ye Preface to Joh. Andrews". Here he is referring to his friend Henry Fielding's 1742 work, Joseph Andrews, in which Fielding explains that a character portrait requires attention to detail and a degree of realism, while caricature allows for any degree of exaggeration. Fielding positions himself as a "Comic Writer" and Hogarth as a "Comic Painter", and dismisses the caricaturists as he dismisses the writers of burlesques.[6] Fielding wrote in defence of Hogarth in the preface:

He who should call the Ingenious Hogarth a Burlesque Painter, would, in my Opinion, do him very little Honour; for sure it is much easier, much less the Subject of Admiration, to paint a Man with a Nose, or any other Feature of a preposterous Size, or to expose him in some absurd or monstrous Attitude, than to express the Affections of Men on Canvas. It hath been thought a vast Commendation of a Painter, to say his Figures seem to breathe; but surely, it is a much greater and nobler Applause, that they appear to think.[7]

On the original subscription ticket, a further section detailed the forthcoming issue of Marriage à-la-mode with details of its content, price and issue date. A copy of the ticket finished with Hogarth's signature, a wax seal and an acknowledgement of receipt from a "Mr McMillan" is held by the British Library. In 1822, the print was re-issued in its own right, minus the subscription details, by William Heath.

See also

Notes

References

- Fielding, Henry (1742). Joseph Andrews.

- Hogarth, William (1753). The Analysis of Beauty.

- Hogarth, William (1833). "Remarks on various prints". Anecdotes of William Hogarth, Written by Himself: With Essays on His Life and Genius, and Criticisms on his Work. J.B. Nichols and Son. p. 416.

- Lynch, Deidre (1998). The Economy of Character: Novels, Market Culture and the Business of Inner Meaning. University of Chicago Press. p. 332. ISBN 0226498204.

- Mayer, Robert (2002). Eighteenth-Century Fiction on Screen. Cambridge University Press. p. 240. ISBN 0521529107.

- Paulson, Ronald (1992). Hogarth: High Art and Low, 1732–50 Vol 2. Lutterworth Press. p. 508. ISBN 0718828550.