Charles Green (31 January 1785 – 26 March 1870) was the United Kingdom's most famous balloonist of the 19th century.[1] He experimented with coal gas as a cheaper and more readily available alternative to hydrogen for lifting power. His first ascent was in a coal gas balloon on 19 July 1821. He became a professional balloonist and had made 200 ascents by 1835. In 1836, he set a major long distance record in the balloon Royal Vauxhall, flying overnight from Vauxhall Gardens in London to Weilburg, Duchy of Nassau (Germany)[1] a distance of 480 miles (770 km). By the time he retired in 1852, he had flown in a balloon more than 500 times.[2]

Green is credited with the invention of the trail rope as an aid to steering and landing a balloon.[1]

A trophy named after him, the "Charles Green Salver", is awarded by the British Balloon and Airship Club (BBAC) for exceptional flying achievements or contributions in ballooning.[2] The trophy was originally given to Green by Richard Crawshay after a balloon trip in Norfolk. Recipients have included Brian Jones and Bertrand Piccard for the first round-the-world balloon flight. Green was included in the ballooning hall of fame in 1999.[3]

Early life

Charles Green was born on 31 January 1785 at 92 Goswell Road, London the son of Thomas Green, a fruiterer. Green on leaving school joined his father's business.[4]

Balloonist

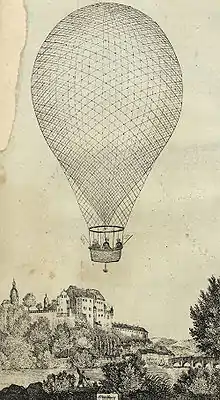

Green's first ascent was from the Green Park, London, on 19 July 1821, by order of the government, at the coronation of George IV, in the first ever balloon filled with carburetted hydrogen gas.[1][4] The trip got into trouble and he had to be rescued by a passing ship captained by the mate, Francis Cheesman, who ran the silk through with his bowsprit, releasing the gas. After that time he made 526 ascents. On 16 August 1828 he ascended from the Eagle Tavern, City Road, on the back of his pony, and after being up for half an hour descended at Beckenham in Kent. In 1836 he constructed the Great Nassau balloon for Gye and Hughes, proprietors of Vauxhall Gardens, from whom he subsequently purchased it for £500, and on 9 September in that year made the first ascent with it from Vauxhall Gardens, in company with eight persons, and, after remaining in the air about one hour and a half, descended at Cliffe, near Gravesend. On 21 September he made a second ascent, accompanied by eleven persons, and descended at Beckenham in Kent. He also made four other ascents with it from Vauxhall, including the celebrated continental ascent, undertaken at the expense of Robert Hollond, M.P. for Hastings, who, with Monck Mason, accompanied him. They left Vauxhall Gardens at 1:30 p.m. on 7 November 1836, and, crossing the channel from Dover the same evening, descended the next day, at 7 a.m., at Weilburg in Nassau, Germany, having travelled altogether about five hundred miles in eighteen hours.[1] This journey was celebrated with a painting by John Hollins that is now in the National Portrait Gallery in London.[6] The painting shows Green, John Hollins (the artist), Robert Hollond M.P. Sir William Milbourne James, Thomas Monck Mason and Walter Prideaux.[6] On 19 December 1836 he again went up from Paris with six persons, and on 9 January 1837 with eight persons. The Great Nassau ascended from Vauxhall Gardens on 24 July, Green having with him Edward Spencer and Robert Cocking. At a height of five thousand feet Cocking liberated himself from the balloon, and descending in a parachute of his own construction[2] into a field at Burnt Ash Farm near Lee. Cocking was killed on reaching the ground.[7] The balloon came down the same evening near Town Malling, Kent, and it was not until the next day that Green heard of the death of his companion.[4]

In 1838 Green made two experimental ascents from Vauxhall Gardens at the expense of George Rush of Elsenham Hall, Essex. The first took place on 4 September, Rush and Edward Spencer accompanying the aeronaut. They attained the elevation of 19,335 feet (5,893 m), and descended at Thaxted in Essex. The second experiment was made on 10 September, and was for the purpose of ascertaining the greatest altitude that could be attained with the Great Nassau balloon inflated with carburetted hydrogen gas and carrying two persons only. Green ascended with Rush for his companion, and they reached the elevation of 27,146 feet (8,274 m), or about five miles (8 km) and a quarter, as indicated by the barometer, which fell from 30.50 to 11 inHg (1033 to 373 hPa), the thermometer falling from 61 to 5 °F (16 to −15 °C), or 27 °F below freezing point. On several occasions this balloon was carried by the upper currents between eighty and one hundred miles per hour (130–160 km/h).

On 31 March 1841 Green ascended from Hastings, accompanied by Charles Frederick William, duke of Brunswick, and in five hours descended at Neufchatel, about ten miles (16 km) south-west of Boulogne. His last and farewell public ascent took place from Vauxhall Gardens on Monday, 13 September 1852. In 1840 he had propounded his ideas about crossing the Atlantic in a balloon, and six years later made a proposal for carrying out such an undertaking.

Many of his ascents were made alone, as when he went up from Boston in June 1846, and again in July when he made a night ascent from Vauxhall. During his career he had many dangerous experiences. In 1822,[8] when ascending from Cheltenham, accompanied by Mr. Griffiths, some malicious person partly severed the ropes which attached the car to the balloon, so that in starting the car broke away from the balloon, and its occupants had to take refuge on the hoop of the balloon, in which position they had a perilous journey and a most dangerous descent, when they were both injured. Mr. Green received a serious contusion on the left side of the chest, and Mr. Griffith a severe injury of the spine.[9] This is the only case on record of such a balloon voyage. In 1827 Green made his 69th ascent, from Newbury in Berkshire, accompanied by H. Simmons of Reading, a deaf and dumb gentleman, when a violent thunderstorm threatened the safety of the balloon.[4] On 17 August 1841, on going up from Cremorne with Mr. Macdonnell, a jerk of the grappling-iron upset the car and went near to throwing out the aeronaut and his companion. Green was the first to demonstrate, in 1821, that coal-gas was applicable to the inflation of balloons. Before his time pure hydrogen gas was used, a substance very expensive, the generation of which was so slow that two days were required to fill a large balloon, and then the gas was excessively volatile. He was also the inventor of the "guide-rope", a rope trailing from the car, which could be lowered or raised by means of a windlass and used to regulate the ascent and descent of the balloon.

Family life

Green married Martha Morrell and they had a son George Green, who had made 83 ascents with the Nassau balloon[4] After living in retirement for many years he died suddenly of heart disease at his residence, Ariel Villa, 51 Tufnell Park, Holloway, London, 26 March 1870.[4]

He is buried in the eastern side of Highgate Cemetery. His monument is a small pedestal surmounted by the sculpted top half of a hot-air balloon.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Balloon records, accessed May 2009

- 1 2 3 Charles Green Salver Archived 4 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, BBAC, accessed May 2009

- ↑ Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI), Ballooning Commission Hall of Fame Archived 18 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine, accessed May 2009

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dictionary of National Biography (1885–1900), by G. C. Boase, Published 1890 a publication now in the public domain.

- ↑ John Hollins, National Portrait Gallery, London, accessed May 2009

- 1 2 A Consultation prior to the Aerial Voyage to Weilburgh, 1836, John Hollins, 1836, National Portrait Gallery

- ↑ Times, 25, 26, 27, and 29 July 1837

- ↑ The Strabane Morning Post 6 August 1822 reported that £20,000 had been bet on the outcome of the flight

- ↑ "The history and antiquities of Ecton" by John Hall

- Bacon, John M. The Dominion of the Air; the story of aerial navigation, Chapters VI-VII, reprint. ISBN 1-4065-0417-3.