| Charles de Lorraine | |

|---|---|

| Duke of Mayenne | |

| |

| Born | 26 March 1554 Alençon |

| Died | 3 October 1611 (aged 57) Soissons |

| Spouse | Henriette de Savoie-Villars |

| Issue | Renée de Lorraine, duchess of Ognano Henri de Lorraine, duke of Mayenne Charles Emmanuel de Lorraine, count of Sommerive Catherine de Lorraine |

| House | House of Lorraine |

| Father | François de Lorraine, duke of Guise |

| Mother | Anne d'Este |

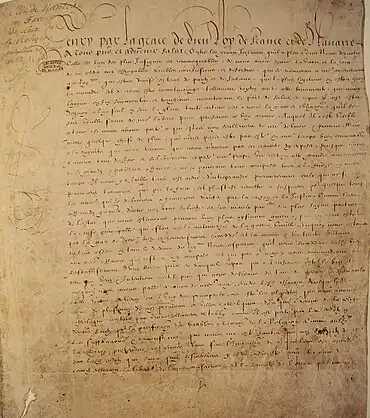

| Signature | |

Charles de Lorraine, duc de Mayenne (26 March 1554 –3 October 1611)[1] was a French noble, governor, military commander and rebel during the latter French Wars of Religion. Born in 1554, the second son of François de Lorraine, duke of Guise and Anne d'Este, Mayenne inherited his fathers' position of Grand Chambellan in 1563 upon his death. He fought at the siege of Poitiers for the crown in 1569, and crusaded against the Ottomans in 1572. He served under the command of the king's brother Anjou during the siege of La Rochelle in the fourth war of religion, during which he was wounded. While the siege progressed, his uncle was killed by a cannonball, and he inherited his position as governor of Bourgogne. That same year, his marquisate of Mayenne was elevated to a duché pairie. He travelled with Anjou when he was elected as king of the Commonwealth and was a member of his court there until early 1574 when he departed on crusade again. Returning to France, he served in the fifth war of religion for Anjou, now king Henri III of France, but his badly underfunded army was unable to seriously impede the Protestant mercenary force under Casimir. He aligned himself with the Catholic Ligue that rose up in opposition to the generous Peace of Monsieur and fought in the sixth war of religion that resulted, serving at the sieges of La Charité-sur-Loire and Issoire. During 1576, he married Henriette de Savoie-Villars, securing a sizable inheritance in the south west, and the title of Admiral on the death of her father in 1578. Mayenne was granted full command of a royal army during the seventh war of religion in 1580, besieging the Protestant stronghold of La Mure successfully, and clearing several holdout towns after the peace. In 1582 he was obliged to surrender his title of Admiral to Joyeuse, a favourite of Henri. The following year he was involved in an abortive plan to invade England, though it came to nothing due to lack of funds.

In 1584, the king's brother Alençon died, and the Protestant Navarre became heir to the throne. This was unacceptable to Mayenne, and many other radical Catholics across France. Resultingly, Mayenne, his brother Guise and various family allies formed a second Catholic ligue at Nancy in September 1584, to push the succession of Cardinal Bourbon, Navarre's Catholic uncle. They formed a compact with Philip II of Spain in December, and entered rebellion against the crown in March 1585. Mayenne seized many of the cities of his governate, and the crown was forced to terms in July, conceding to the ligue that Navarre would be excluded from the succession, and that the crown would conduct a war on heresy. Over the following years, Mayenne vigorously pursued attempts to campaign against the Protestants of the south, however Henri's participation was half hearted, and on a frustrated return to Paris in early 1587, Mayenne was at minimum sympathetic to a failed ligueur plan to seize the capital. Returning south he captured Monségur in mid 1587 but was increasingly unable to make progress for lack of funds. In May 1588, Henri engineered a showdown with the radical Catholics of the capital, but was bested and driven from the city. Forced to make concessions he agreed to establish an Edict of Union, with religiousity overriding Salic Law in determining succession, and to appoint Mayenne to lead one of his principal armies for a war against heresy. At the Estates General, demanded by the ligue, that was called a few months later, the Third Estate demanded the funds they offered be given directly to Mayenne. At a breaking point, Henri arranged for the assassination of the duke of Guise and Cardinal Guise in December, upon which his kingdom erupted into broad rebellion.

In February 1589, Mayenne accepted appointment by the Seize regime in Paris as lieutenant-general of the kingdom, he visited many ligueur aligned cities in the north east, reorganising their administrations as best he could on lines that suited him. In May he fought with Henri outside Tours, but was pushed back. Henri now allied with his Protestant heir Navarre, and the two began a campaign towards the capital that culminated in a brief siege at the end of July, that was broken by the Assassination of Henri III on 1 August. With Navarre now the royalist king, Mayenne was able to secure further defections to the ligueur cause from cities and grandees who had previously remained loyal. He repeatedly clashed with Henri in Normandie, first at Arques then at Battle of Ivry, being bested both times. Henri moved to besiege Paris after the latter, and it was only with Spanish aid that Mayenne was able to save the capital. During 1592 he again required Spanish aid to assist with rebuffing the gruelling siege of Rouen. Considerably indebted to the Spanish, he assented to the calling of an Estates General in 1593 to choose a new king, Bourbon having died. The assembly was unable to come to much agreement, and Henri converted to Catholicism during the proceedings, removing a key hurdle to his acceptance. In 1594, Paris opened its gates to him, and Mayenne was forced to retreat to Bourgogne. After the failure of one final campaign at the Battle of Fontaine-Française in July 1595, he abandoned the Spanish and prepared to return to the royalist camp. By his submission in January 1596 he was returned to loyalty, and received 3 surety towns, a large bribe and a reduced version of the governorship of Île de France. He fought with the king against the Spanish at Amiens, and thereafter faded into retirement. He died in 1611.

Early life and family

Siblings

Charles de Lorraine, born in 1554, was the second son of François de Lorraine, duke of Guise and Anne d'Este. His elder brother Henri de Lorraine was born in 1549, while his younger brother Louis de Lorraine was born in 1554. He also had an elder sister, Catherine de Lorraine one year junior of Henri.[2] In a rendition of the Adoration of the Magi, commissioned by François for the hôtel de Guise in Paris, the duke is depicted as one of the Magi, while Mayenne and his elder brother appear as the Magi's pages.[3]

Marriage and children

In 1576, Mayenne secured a marriage to the wealthy heiress Henriette de Savoie-Villars, who brought with her a dowry of 1,275,000 livres.[4] She also provided an inheritance in the south west, an area the Lorraine's traditionally had little influence. Among these lands were the comté de Montpezat.[5] Her father Admiral Villars also promised that Mayenne would inherit his office of Admiral, the second most senior military office in France, upon his death.[6] The two were married on 6 August at Meudon, the first of three weddings the Lorraine's celebrated that year. Together they would have:[7]

- Renée de Lorraine (d. 1638) married Mario Sforza and had issue[8]

- Henri de Lorraine, duke of Mayenne (1578–1621) married Henriette Gonzague, daughter of Louis de Gonzague, Duke of Nevers[9]

- Charles Emmanuel de Lorraine, Count of Sommerive (1581–1609) never married;[10]

- Catherine de Lorraine (1585–1618) married Carlo di Gonzaga, Duke of Mantova[11]

A royalist by 1598, Mayenne would marry a son and a daughter into the Nevers family, which had ultimately sided with Henri IV.[12]

Personality

Much like his brother Guise, Mayenne had little interest in the ascetic piety that dominated Henri's court.[13] He had a reputation for drunkenness, and had to be taken home in 1593 by the financier Zamet after he got too drunk one night. This preponderance for alcohol impacted his health, and by the end of his life he was in bad shape.[14] Of an overall violent disposition, in 1587 when a captain named Sacremore asked for his daughter in law's hand in marriage after admitting to having already seduced her, Mayenne stabbed him to death with his own hands.[15][13] He had also kidnapped the Protestant noblewoman Anne de Caumont as a prospective bride for his son Henri de Lorraine in 1586.[16]

Reign of Charles IX

On the death of his father in 1563, his eldest son, Guise inherited the office of Grand Maître from his father. Mayenne meanwhile inherited a slightly lesser but still prestigious office in the king's household, that of Grand Chambellan, responsible for the king's furniture and clothes. He held this office until 1589.[17] Despite the prestige of this position, Henri III allowed it to have little real authority during his reign, though he permitted Mayenne to share his table alongside the Gentilhomme de la Chambre.[18]

Military service

The young Mayenne saw his first military service during the third war of religion. Together with his elder brother, Guise, he participated in the defence of Poitiers against Admiral Coligny's Protestant army. Upon hearing of Coligny's approach to the city, the two men, alongside the governor of Poitou Guy de Daillon had hurried in before the investment of the city was realised, in the hopes that they would have a chance to revenge themselves on their hated rival.[19] Mayenne and Guise successfully led the resistance to Coligny, overseeing the defence and the rebuffing of attempted assaults. As such Coligny was held up long enough for the king's brother Anjou to arrive with the main royal army, crushing Coligny at the Battle of Moncontour shortly thereafter.[20]

Mayenne continually pestered his uncle Lorraine to secure for him a residence in Paris. Aside from these expensive requests, Lorraine was generally concerned for the young boy, as he had developed a dangerous habit of wearing the colour green for his livery, a colour already in use by the duke of Anjou.[21]

Crusade

Mayenne's family had been prosecuting a feud with Coligny, ever since the assassination of his father, in 1563. This greatly frustrated the crown, seeing the greatly destabilising threat having its two most prominent families at each other's throat posed. In 1571 while France was once more at peace, the feud threatened to flare up. To combat this in October, Charles intended to force another show of reconciliation between Guise, Mayenne and Aumale and the Admiral.[22] In a show of strength, Mayenne and Guise entered Paris in force on 14 January, accompanied by 500 retainers.[23] Soon thereafter, Mayenne departed France in April to go on Crusade against the Ottomans, he took with him 200 of the families retainers, a curious move if the family was intending a showdown with Coligny.[24][25] Mayenne travelled to Corfu where he served with the Venetians for a time, before returning to France.[26] In Mayenne's absence, it became apparent their entry to Paris back in January had been aimed at ensuring they did not concede to peace without a show of the families power. Guise arrived at court to make peace with Coligny on 12 May.[24]

Lorraine's frustration at his nephews were not over however, as Mayenne had chosen to depart on crusade without receiving royal dispensation to depart France. Lorraine was compelled to write a grovelling letter to the king in which he pleaded for Charles to have 'pity on a poor hopeless and debauched boy'. Mayenne would be forced to seek pardon from the king upon his return.[27]

In the wake of the Massacre of Saint Bartholomew, the Protestant stronghold of La Rochelle, flooded with refugees, entered rebellion against the crown. This was unacceptable to Charles, and he dispatched Anjou, to take command of an effort to besiege the rebel city into submission. Anjou arrived in front of the city in early 1573, and began a vigorous siege effort. He was accompanied in his arrival at the city by the cream of the French nobility, among them the Protestants Navarre and Condé; the firmly Catholic Nevers and members of the Guise family, among them Mayenne. Mayenne was among the notables who Anjou included on his war council, to advise on the conduct of the siege. The siege dragged on inconclusively for months, frustrated by the bickering of its commanders and supply issues. By the summer of 1573, Anjou was looking for an exit, and found one when he was elected king of the Commonwealth. A peace was concluded with the still defiant La Rochelle soon after on 25 June.[28] During the conduct of the siege, Mayenne had received a wound to his leg from the defenders.[29]

Bourgogne

At the age of 19, Mayenne became governor of Bourgogne in March 1573 while the siege was still raging, succeeding his uncle Aumale who had died in the fighting at La Rochelle.[30] Aumale in turn had succeeded his father the first duke of Guise, meaning that the Lorraine family had held the governate of Bourgogne since 1543.[31] Despite this long running control of the province, Aumale possessed no lands in the governate, and as such was forced to rely on a clientele network to exert his control.[32] In September 1573, Charles elevated the marquisate of Mayenne to a duché-pairie for the young prince.[13][33]

Mayenne accompanied the new king Anjou to the Commonwealth after the conclusion of the siege, as a member of his household. He was with the king for his first meeting with foreign ambassadors to the court.[34] Having stayed with Anjou for several months, Mayenne departed on 20 April, to enjoy the waters at Lucca before again engaging in a brief campaign against the Ottomans.[35] Anjou complained to his favourites who had not departed, about the predilection for crusading of Mayenne and the other departees.[36]

He arrived at Dijon for his ceremonial entry into the capital of his governate the following year, where he was met by a delegation from the city comprising the Parlement, mayor, council and other elites. Together they entered Dijon, with Mayenne refusing the privilege of entering under a 'canopy', a covering held up by four townsmen, as a way of demonstrating his modesty.[37] This privilege was greatly vaunted by the elite, with Condé suing for the right to do so in his governate.[38] In the town, Mayenne was subject to an obsequious speech from the mayor, pledging their loyalty, and willingness to die at his feet in service to the king.[39] Mayenne was determined to have a more hands on role in Bourgogne than had his uncle, who almost entirely ignored his governorship during his lifetime.[40]

Reign of Henri III

In May 1574, Charles died, and without a child his brother Anjou succeeded to the throne. For the coronation of Anjou, now styling himself Henri III, Mayenne and the Lorraines had an important role to play. Mayenne, alongside his brother Guise and cousin Aumale, took the role of the three lay peers for the ceremony, while Cardinal Guise crowned the king.[41]

In the confusing combats that characterised the fifth war of religion, Mayenne led an army in late 1575 facing off against a Protestant mercenary force under Casimir von Pfalz-Simmern that had invaded the kingdom. It was one of two main royal armies, the other being commanded by Henri himself at Gien to defend the approaches to Paris.[42] Encamped at Vitry-le-François, Mayenne's 10,000 men were ravaged by hunger and lack of pay and were able to do little more than shadow Casimir as he moved to Dijon on 31 January 1576, and then Moulins on 4 March, where he united forces with the politique brother of Henri, Alençon. United, the rebel army threatened a march on Paris that Henri no longer had the troops or funds to stop.[43]

First Catholic ligue

As a result, in May 1576 Henri was forced into a generous peace with the Protestant and politique rebels. Many concessions were granted to the Protestant nobility, with the prince of Condé afforded the border town of Péronne. The governor of Péronne and his clientèle reacted furiously, and formed the nucleus of what was to become a national Catholic Ligue in opposition to the peace. Henri was alarmed by the rapid spread of the movement, and suspected the hand of the Guise family lay behind it. To this end in August, he had Mayenne, Guise and their ally the duke of Nemours who he suspected of involvement swear an oath to uphold the edict of Beaulieu.[44] During the Estates General of 1576, called as a term of the peace, one of Henri's favourites, Saint-Sulpice was murdered by a favourite of Alençon. Mayenne considered himself a protector of the young man, and vowed he would avenge himself on the killer.[45]

The ligue was soon able to force Henri to break off from the peace, beginning the sixth civil war in early 1577. Mayenne was among the figures in the council who had advocated for breaking the peace, and resisting calls to bring the new war to an early close.[46] The short peace had however re-secured the loyalty of the king's brother to the royal cause, and he volunteered to lead the royal army against his former rebel compatriots. He had little military experience, and authority for the operations of the army would in fact lie with Nevers, Guise and Mayenne. The force set about a siege of La Charité-sur-Loire, and then Issoire, putting each to a violent sack. However the army was starved of funds, Henri unable to secure concessions from the estates, and as such by the middle of 1577 it had largely disintegrated, leaving Henri unable to continue prosecuting the war. Mayenne moved off without Alençon with his own force, and on 18 August captured the town of Brouage on the Atlantic coast, with the assistance of Guy de Lansac, securing a considerable supply of salt.[47] Henri was pleased at the reduction, and added Brouage to the royal domain.[48] The Treaty of Bergerac brought the conflict to an end in September. Somewhat harsher than the Peace of Monsieur, it sated the ligue movement for the following 6 years.[49]

At court, relations between the favourites of Henri and the grandee families were fraught. On Mayenne's orders, one of Henri's favourites Saint-Mégrin was butchered as he left the Louvre on 21 July by a gang of 20+ assailants. Rumours had circulated that Saint-Mégrin was attempting to seduce Mayenne's sister in law, the duchesse de Guise.[50] Henri was distraught at the death of Saint-Mégrin, but the favourite was otherwise unpopular at court, so Henri mourned alone. The killing came not long after the famous Duel of the Mignons, which had seen another two of Henri's favourites killed. He arranged for an elaborate commemoration for the three men, overseeing an ostentatious funeral, and entombing them in marble sarcophagi.[51]

Favoured one

Despite rumours of his involvement in the murder of Saint-Mégrin, Henri was happy to permit the transfer of the office of Admiral to Mayenne in 1578. Overall Henri was far more willing to provide major commands to Mayenne than his brother, either due to a greater amount of affection, or a desire to divide the Lorraines by making them jealous of each other.[52]

When Catherine departed on her mission to the south, to sooth the wounds of the civil wars and restore order in provinces that were increasingly fragmented in central control, Mayenne was among those who travelled with her to Montluel for her confrontation with the rebellious former favourite of the king's Marshal Bellegarde, during which an agreement was reached between the Marshal and crown.[53]

The following year, Guise, dissatisfied with his lot, toyed with the idea of bringing the family into a group of Malcontents, alongside the Protestant brother of the elector Palatine Casimir. He and Mayenne met with Casimir to discuss a plan to seize Strasbourg, however ultimately nothing would come of this inter-confessional moment, and the Lorraine family returned to their reputation for crushing heresy.[54]

As a result of the relative favour in which he was held, Mayenne commanded a royal army during the brief civil war in 1580, leading it into Dauphiné against Lesdiguières where he captured the Protestant stronghold of La Mure in October, while Matignon reduced the border town of La Fère up in Picardie.[55][56] With the Treaty of Fleix concluding the conflict by the end of the year, Mayenne was entrusted with ensuring that it was enforced, and obtaining the submission of the holdout towns of Livron and Gap, a task in which he was successful.[33]

He was not however able to hold the office of Admiral for long, as Henri detached Mayenne from it in 1582, so that he could award it to his favourite Joyeuse, whose trustworthiness was beyond question. In return for yielding this most prestigious office, Mayenne was compensated with 120,000 écus and the elevation of his cousin, Charles de Lorraine's seigneurie from a marquisate to a duché-pairie.[57]

He was involved in his families abortive plans for an invasion of England in 1583. Several ships were assembled by Elbeuf in August 1583, with an army to be commanded by Mayenne, and Marshal Brissac. He attended council with Guise and Cardinal Bourbon at the governor of lower Normandie Meilleraye's Château in August to discuss the details of the invasion. Brissac arrived soon thereafter with bad news, sailing was to be postponed due to lack of funds. Mayanne and the Lorraine family would soon be far too busy in domestic events.[58]

Second Catholic ligue

Disaster rocked the crown in June 1584, when the heir to the throne, the king's brother Alençon, died of tuberculosis. This left the inheritance of the throne on Henri's death to the king's distant cousin Navarre, a Protestant. Such a succession was intolerable to many Catholics, among them the Guise family. Mayenne, Guise and Cardinal Guise met in Nancy during September with Maineville a representative of Cardinal Bourbon and agreed to oppose the succession. Cardinal Bourbon, Navarre's Catholic uncle was to be their candidate for the throne. In December the family concluded an alliance with Philip II of Spain (known as the Treaty of Joinville) by which the Guise made many concessions to Spain in return for financial and political support.[59][60] Mayenne and his brother were both signatories to the treaty for the ligueur side.[61] In his capacity as governor of Bourgogne, Mayenne marshalled his clientèle in support of the ligue, while his brother Guise mobilised Champagne, and his first cousins Aumale and Elbeuf prepared for rebellion in their strongholds of Picardie and Normandie respectively.[62]

The ligue movement had two wings, the aristocratic, embodied by the Guise family and the ligue of 1576; and the urban middle class, as typified by the Seize organisation in Paris. While Guise was alive he was tenuously able to hold the two components together in a united purpose, however after his assassination in 1588, Mayenne struggled to replicate this unity, and the ligue movement began to splinter.[63]

War against Henri

No fool to developments in the kingdom, Henri wrote to Guise, Mayenne and Bourbon on 16 March, asking for them to explain what exactly it was they were up to, while pretending that he of course did not believe reports that they were preparing acts of rebellion.[64]

With open hostilities declared on the crown by Guise's armed entry into Châlons on 21 March, Mayenne quickly moved to secure the major cities of his governate. Mayenne was however furious at his brother for, he felt, jumping the gun with his seizure. The two met at Joinville on 21 April, and Mayenne lambasted his brother for having 'too soon declared and taken up arms', Mayenne having preferred a date of 18 April, the day preceding Good Friday.[65] Mayenne argued Guise had allowed Henri to present them as the aggressor and buy off the governors the family had been approaching. Guise retorted that he had been compelled by circumstances, and that to avoid accusation of treason he had ordered Elbeuf to conduct Cardinal Bourbon to Péronne to make a declaration.[66]

Over the following months he would seize Dijon, Mâcon and Auxonne for the ligue. On 7 July Henri was compelled by the deteriorating situation of his control over the kingdom to sign a humiliating peace where he conceded to most of the ligueur demands, including a war against Protestantism.[67] As a term of the peace, Mayenne was granted Beaune as a surety town, alongside possession of the Château of Dijon.[68] The family reunited in Troyes during September 1585 to celebrate their recent victory. Mayenne and Guise, alongside their other relatives participated in numerous festivities, among them a ceremonial burning of a straw figure representing heresy.[69]

War against the Protestants

After passing through Paris in October of that year, Mayenne departed alongside Marshal Biron to pursue the now royal war against heresy through attacks against Condé. To Mayenne's frustration Biron departed the army the following month and returned to the capital.[70]

It became clear in the year that followed that Henri had little interested in prosecuting the war against Protestantism he had agreed to fight. The ligue was happy to take the lead, and Mayenne fought with the Protestant duke of Bouillon in the Saintonge and Périgord.[71] While initially Mayenne had been placed in command of the sole royal army against Navarre, Henri created several new armies under his two chief favourites Joyeuse and Épernon during 1586, and Mayenne's army was left to founder for lack of funds. He found himself bogged down in endless sieges in the Dordogne.[72] Returning to Paris in January 1587, he was furious at the treatment of his army, the numbers having been decimated further by desertions. While in Paris a plan was concocted among the militant ligueurs of the city to seize control of the capital in the future. The group planned to utilise barricades to impede royal movement across the city, however their plan was uncovered by the king, who arrested the ringleaders.[73] Mayenne denied any involvement, meanwhile Poulain, who had revealed the plot to Henri, informed the king that Guise was furious at his brother for planning a coup and leaving him in the dark. Henri was prevented from coming down with a firmer hand on the plotters by the death of Marie de Lorraine in England, who provided the ligueurs a strong martyr that invigorated their cause, with churches throughout Paris mourning her.[74]

Back on campaign, he entered Guyenne in mid 1587, capturing the Protestant stronghold of Monségur, however his advance was increasingly slow and he was unable to prevent Condé and Navarre from uniting forces.[75] Observing his foundering, Catherine de' Medici urged her son to send reinforcements to bolster his campaign, which Henri assented to in August, dispatching forces both to Mayenne and his favourite Épernon who was fighting in Valence.[76]

Day of the Barricades

In May 1588, Henri undertook a showdown with the ligue in Paris, hoping to reassert his flagging authority. Radical Catholics in Paris rose up against him however and enacted the planned uprising that had been aborted in 1587. With Henri humiliated and forced to flee Paris after the Day of the Barricades, he was pushed to make further concessions to the ligue by the Parisian Seize to regain his capital. They demanded he recognise the Sainte-Union, provide them with six surety towns, sell off all Protestant assets and establish Guise and Mayenne as the twin heads of the royal army for a new campaign against Navarre and the Protestants. Guise would lead a royal army out of Poitou, while Mayenne would command one from Dauphiné. Henri capitulated to these demands on 5 July and signed the Edict of Union.[77][78]

Shortly thereafter Henri took a radical step, dismissing all his chief ministers, and bringing in a new set of men, blaming his previous ministers for the disasters of the previous months. Villeroy who had served the king for many years before the abrupt dismissal, offered his services to Henri's enemy Mayenne, and was accepted into the circle of Mayenne's advisors.[79] When Mayenne took charge as lieutenant-general, he would install Villeroy as a fellow conservative presence on the Grand Conseil.[80]

In September an Estates General convened at Blois. The election of deputies for the body was viciously fought between the royalist and ligueur parties. Mayenne worked hard in Bourgogne and Poitou to ensure both regions provided ligueur slates of representatives. The rest of his family did likewise in their respective zones of authority.[81] Henri hoped to use the occasion to regain the initiative he had lost in Paris. However he was to be disappointed, the delegates being largely ligueur in disposition. Only Mayenne was absent among the ligueur leadership from Blois after the deputies arrived, due to his responsibilities leading one of the two royal armies.[82] The Estates took it upon themselves to audit the crown's finances and were not impressed by what they found. The Third Estate resultingly promised a paltry 120,000 écus to keep the kingdoms finances afloat, however in a further twist of the knife these were not to go to the king but instead directly delivered to the crown's armies under the authority of Mayenne and Nevers.[83]

Assassination of the duke of Guise

These continued humiliations and attempts on his authority finally brought Henri to a fateful decision. On 19 December he resolved to execute the duke of Guise and his brother Cardinal Guise, a plan which was carried out from 23 to 24 December. Many theories have been put forward for what finally pushed Henri into the act, among them the request of the estates general for the tax revenue they provided to be given directly to Mayenne.[84] Henri had also received reports that there was considerable jealousy between the more popular and charismatic duke of Guise; and Mayenne, Aumale and Elbeuf, who resented being in his shadow.[85] The killing of the Cardinal was a deeply sacrilegious act, and the ligue and Henri competed to present their version of what had transpired to the Pope. In January, Mayenne dispatched Jacques de Diou, a member of the order of Malta to present the ligueur interpretation to Pope Sixtus V.[86]

On the days of the assassinations, Mayenne was occupied in Lyon preparing for a new offensive against the Protestants. He was able to only narrowly avoid being arrested by agents of the king in the city, and he hurried back to the security of his governate before arranging for the hiring of 6000 Swiss mercenaries.[15][87] This accomplished he left from Bourgogne to Paris on 16 January, accompanied by his sister. On route he passed through many cities, securing their allegiance to the ligue, arriving in Chartres on 5 February shortly after a ligueur coup had thrown out the governor of the city. His entourage arrived in the capital several days later.[15]

Seize

On 12 February, Mayenne, alongside his cousin Aumale, and ally the duke of Nemours presented themselves before the church of Saint-Jean-de-Grève in Paris where they were hailed by ecstatic crowds with cries of 'Long live the Catholic princes!'[88]

The Seize regime in Paris created a Grand Conseil of 40 members to administer the kingdom. They submitted their proposed member list to Mayenne for his approval, and he gave his assent.[89] This body in turn nominated Mayenne as lieutenant général de l'État et Couronne de France in February.[90] He swore his oath accepting the position on 13 March.[91] Mayenne took to his new role with enthusiasm, quickly raising a ligueur army to fight Henri and Navarre.[92] He further began levying taxes in his governate in the manner of a king.[93] This office gave him far broader authority than the traditional lieutenant-general of the kingdom, whose purview was largely military. He confirmed offices as minor as the 'master of the mint' for the city of Poitiers, and had the authority to appoint figures to offices from the governors of regions to royal sergeants.[94] He worked closely with the Italian financier Sébastien Zamet, who lent money to the ligueurs. The two men regularly dined together in Paris, Mayenne having taken up residence in the Hôtel de la Reine, formerly inhabitaed by Catherine de' Medici.[95][96] He and the Seize collaborated to install a new leadership of the Paris Parlement after the purge of the royalists from the body, with Barnabé Brisson established as prémier president.[97]

Mayenne was keen to secure the grandee Nevers for the ligueur cause, but despite his incessant letters Nevers remained loyal to the king.[98]

Provincial reaction

In total across France, roughly half of the 50 largest cities defected to the ligue in the wake of the assassinations at Blois. Mayenne would be intimately involved in many of their rebellions.[99]

Rouen

Rouen experienced its own Day of the Barricades in February 1589, when a ligueur regime succeeded in a coup to take the key city. Carrouges, governor of Rouen, initially tried to maintain his place in the city hierarchy following the coup, claiming a conversion to the ligueur cause. Few were convinced by this eleventh hour change, and Mayenne himself visited Rouen on 4 March, to install a ligueur provincial council, with the more reliable Villars, Meilleraye and his brother Pierrecourt at its head. Mayenne was far more pleased with this regime, having induced it with an aristocratic character through the appointment of friendly elite ligueurs. It contrasted with the Seize regime in Paris, which Mayenne viewed with distaste.[100][101] He had been greeted on his entry to the city by ligueurs keen to demonstrate their piety, the population filing through the streets for hours in a barefoot procession.[102] Before departing, Mayenne rewarded the city with a series of letters patent in which he reduced their taxes and ordered many offices to be suppressed on the death of their incumbent. Despite this the need to reward his allies would mean that he would attempt to keep the offices active by assigning them to new men, though he was opposed in this by the Rouen Parlement.[103]

In Spring 1590, Mayenne appointed Tavannes, a protégé from Bourgogne, and a noble of he felt, appropriately august lineage, as the head of the provincial council.[104] Tavannes proved a poor choice, quickly alienating the elite of Rouen, and he in turn was ousted from leadership in 1591 by the opportunist governor of Le Havre, Villars.[105] When Mayenne visited Rouen in 1591, Villars camped outside the city with an army, and threatened to defect to the royalist side unless Tavannes was removed as ligueur governor of Normandie. Mayenne acceded, and appointed his own son governor, with Villars to act with the full powers of governor until the boy was of age.[104] He further made Villars the ligueur Admiral of France.[106]

Toulouse

Toulouse was overtaken by a ligueur coup in early 1589 also, under the overall authority of the bishop Comminges. Comminges' leadership of the important city was challenged by Mayenne's appointee as military leader of Languedoc Joyeuse, entering the city on 30 September, he secured it for Mayenne's moderate faction of the ligue after a brief power struggle.[107]

Troyes

In Troyes, Mayenne arrived with his troops on 24 January, all officials were expected to swear an oath to the ligue in his presence, any who refused were expelled from the city. Mayenne established the second son of the late duke Chevreuse, who was only 11 years old, as governor, forming a governors council in the city for him. After seven weeks of this arrangement, the council was superseded in name as a 'new' ligue council.[108] This council would form one of the twelve provincial councils that the ligue operated.[109] Such councils had authority over both financial and military matters, as well as more minute financial decisions, as to determine the appropriateness of ransoms for captured nobles.[110] In theory these provincial councils were to enact orders received from the main Grand Conseil in Paris, and thus Mayenne, but they often had an independent streak.[111] During December 1592, Mayenne wrote to the ligueur administration of Troyes, warning them about the rumours of Henri's plans to convert to Catholicism, reminding them that he would still be excommunicated and thus unworthy to rule France, as such not invalidating their rebellion. Officials in the town were warned that if they accepted his conversion, they would be placed under house arrest.[112]

Champagne

Mayenne, in his capacity as lieutenant-general of the kingdom, appointed the young duke of Guise to the position his father had occupied, governor of Champagne.[113] He followed this up with the appointment of the baron de Rosne and Saint-Paul in overall authority as lieutenant-general of Champagne, giving them the effective powers of governor due to the imprisonment of the young duke of Guise. De Rosne had previously served the late duke of Guise as his governor of Châlons-sur-Marne, while Saint-Paul had been made lieutenant-general of Reims by Guise to counter Dinteville's influence during the 1580s. Dinteville was the lieutenant-general of the kingdom according to the king.[114] In 1593 Mayenne elevated Saint-Paul to the rank of Marshal as he became increasingly ambitious in Champagne.[115]

Dijon

In his governate of Bourgogne, Mayenne was in a strong position at the death of Guise. His client Jacques La Verne was the mayor of Dijon and he had further clients among the Parlementaires. He appointed the sieur de Fervaques as lieutenant-general of the province for the ligue to replace the royally appointed comte de Charny. He had first nominated Fervaques back in October, for the confirmation of Henri, however that process was now done away with.[116] Yet La Verne was not quick to seize Dijon for the ligue in the wake of news reaching the city and only when Mayenne himself arrived on 5 January was Dijon secured for the Sainte Union. On 16 January he assembled the city council, and quoted scripture to prove that they owed obedience to the church before they owed anything to Henri. Before departing Mayenne oversaw the taking of an oath, and made the city grandees promise to obey La Verne and not allow troops within their walls without his permission.[117] La Verne was more independent than Mayenne had hoped, and engaged in a power struggle with Fervaques over which of them would control the Château of the city. In April 1589 La Verne imprisoned Fervaques for refusing to swear the ligueur oath.[118] Mayenne was increasingly frustrated by his client, and turned to several Parlementaires, supporting them in the mayoral elections of 1590 and 1591 against La Verne, but they were unable to overcome his 99% vote margins. In 1592 Mayenne succeeded in getting his candidate elected, La Verne never having been secure in his dictatorial control of the Dijon council.[118] Though the following year La Verne would triumph again, Mayenne would be rid of his former client in 1594, disposing of him permanently after La Verne attempted to hand the Château over to Henri, having him executed.[119]

Bourgogne

Mayenne's efforts in Dijon were part of a large picture in Bourgogne, of his attempts to influence mayoral elections in the favour of his political interests.[120] He wrote to Fervaques from Paris about his plans for the province, promising to send more troops so that Bourgogne could be 'cleansed of vermin', by which he meant any enemies of the ligue. In April he replaced Fervaques, who had proved more royalist than anticipated with the baron de Sennecey a long time client of the Lorraines.[121]

Provence

The ligue movement in Provence was headed by the comte de Carcès who aligned himself with Mayenne through a marriage to his daughter in law.[122] Mayenne's candidate for leadership of the ligue in Provence was opposed by Hubert de Vins and his sister Chrétienne d'Aguerre, comtesse de Sault. After the death of her brother in November 1589 she took charge of their faction, and invited the duke of Savoie into Aix. He entered in November 1590, bringing about the triumph of the faction of Sault over the faction preferred by Mayenne, that of Carcès.[122]

Provincial overview

In total there were 12 provincial ligueur councils across France, Agen, Amiens, Bourges, Dijon, Le Mans, Lyon, Nantes, Poitiers, Riom, Rouen, Toulouse and Troyes. Mayenne would have preferred to govern without them and where possible he shaped them towards his aristocratic vision of the ligue.[80]

War against Henri

Departing from Paris in the wake of his elevation to lieutenant-general of the kingdom, Mayenne headed to Orléans, which had rebelled against its governor Entragues on 23 December having got word of Henri's coup in Paris. Henri was keen to re-secure the city, but Mayenne reached Orléans first. Upon his entry the royal garrison abandoned the citadel which they had retreated to after losing the main city.[123] Having returned to Paris, he departed again on 8 April at the head of a new army assembled at Étampes which numbered over 10,000 men. He subdued Vendôme in mid April causing consternation in the royal camp at Tours. On 28 April Mayenne participated in a bloody skirmish with the comte de Brienne, brother in law to Henri's favourite Épernon, 50 ligueurs were killed but Brienne surrendered, a cause for great celebration in Paris.[124]

Alliance of the kings

Conscious of his incredibly tenuous position in the wake of having assassinated the duke, Henri turned to Navarre for support and the two king's entered a compact on 3 April. The treaty specified that Navarre was to march against the forces under Mayenne, and drive him from the field. This accomplished, they devised a plan to seize back Paris for the crown, with both to approach from different directions.[125]

Mayenne was almost able to capture the king in a surprise attack at Tours on 8 May, catching Henri off guard during a private visit to the Abbey of Marmoutier outside the walls. Henri was able to retreat into Tours, and Mayenne's artillery pummelled Henri's residence in the hours that followed. He sent appeals to Navarre, who promptly forwarded reinforcements. With reinforcements at hand, Henri was able to rebuff Mayenne at a narrow bridge into the city and Mayenne was forced to withdraw soon thereafter.[126][127] The battle had cost the lives of 200 royalists, among them a member of the Quatre Cinq, Henri's bodyguard unit which had carried out the murder of the duke of Guise. Mayenne ensured the head was dispatched to Paris to be displayed, while pamphleteers in the capital proclaimed his great victory at Tours.[128] That same month George d'Avoy approached Henri, offering to kill Mayenne. Henri was suspicious and under interrogation George confessed to being sent by Mayenne to murder Henri.[129] Rebuffed at Tours, Mayenne moved into Normandie, seizing Alençon. Normandie was in the midst of a peasant revolt known as the Lipans and thousands flocked to Mayenne's banner, though he was uninterested in their cause and rejected offers from them to aid him.[130]

Ultimately, Mayenne and Aumale vainly sought to halt the advance of the two men's forces, and the royalists captured Étampes, Montereau and Senlis.[131] He visited the ligueur controlled city of Reims in early July, causing much panic in Châlons, the only major city in Champagne still loyal to the royalist cause.[132] Returning to the capital, Mayenne busied himself trying to strengthen the outer perimeter of Paris in preparation for what seemed likely to come.[133] In this effort, he vainly sought to stop them from capturing the strategic town of Pontoise on 26 July which controlled much of the supply into Paris, but his relief effort arrived too late.[134] By the end of July the royalists were in a position to invest Paris.[135] Mayenne looked desperately for outside assistance, receiving a welcome coup when forces under Claude de La Châtre ligueur governor in Berry arrived to bolster the garrison. He looked to Felipe and the duke of Parma for further aid, promising Felipe the title of 'protector of the kingdom' and an allowance to keep any fortresses he captured from Protestants during a campaign into France.[136]

Reign of Henri IV

_-_Henri_IV%252C_King_of_France_(1553-1610)_-_RCIN_402972_-_Royal_Collection.jpg.webp)

New order

The death of the king on 1 August represented a significant opportunity for Mayenne and the ligue, as the prospect of a Protestant king was no longer a future hypothetical for the cities and nobles of France. Mayenne dispatched the Réglement de l'Union to various cities which had maintained their loyalty, or a calculated neutrality. He made concerted efforts in the moment to bring over Châlons, the only significant royalist hold out in Champagne, but his letters were ignored and the city swore itself to Henri IV.[137] Several of Henri's favourites defected to Mayenne on the king's death, bringing over their cities with them. Chief among them Vitry the governor of Meaux and Entraguet the governor of Orléans.[138]

Poitiers

Among the cities to defect was Poitiers, which quickly took the opportunity to formally declare itself for the ligue, with an oath on 21 August.[139] Despite their newfound affiliation to the ligue, Poitiers had more in common with the Seize in Paris than Mayenne's vision of the ligue. The city bitterly resisted his appointment of La Guierche as governor of Poitou, the people of Poitiers wrote to Mayenne to complain about him, and in January 1591, radical ligueurs besieged La Guierche in his Château eventually taking him prisoner, before being reconciled with him after the destruction of the Château. In September 1591, after having slipped back into the city, the council demanded La Guierche leave, and go fight with Mayenne's army.[140] The city also circumvented Mayenne's authority through direct dealings with the Spanish.[141] Mayenne assured Poitiers he would dispatch the young duke of Guise, who had escaped captivity in August 1591, to the city. Mayenne granted the prince a commission to take command over all ligueur operations in central and western France.[142] Mayenne would ultimately disappoint Poitiers in their ambition to have Guise as their governor, selecting instead Marshal Brissac. The city proved amenable to this choice however, in a way they had never been with the late La Guierche.[143]

Henri's death, meant that the ligueur candidate for the succession was now king as Charles X in ligueur cities, he would however remain a captive until his death. Mayenne took the opportunity to abolish the Grand Conseil in its original form, re-establishing it on lines more agreeable to him as an advisory council for his leadership. This was despite the protestations of the Seize which had originally constituted it.[144] The Seize formally petitioned him in February and April to reconstitute its original form, but Mayenne ignored them.[145]

Arques

The siege of Paris was made unviable by the death of the king, and Navarre, now styling himself Henri IV moved north into Normandie with the remnants of the royal army. Mayenne gave chase in September, declaring that he would drive Henri into the sea, or bring him back to Paris in chains. The two sides met at Arques for a series of engagements in September, during which Mayenne was handed a bruising defeat.[146][147][148]

Late in the year, Mayenne organised the capture of the bishop Nicolas Fumée the Bishop of Beauvais for the crime of recognising Henri IV as the new king. Mayenne brought him to Paris and demanded the Papal Legate sentence him to death, but the Legate was uninterested, and Mayenne therefore ransomed the prelate for 900 écus.[149] In other cases, Mayenne and Henri took it upon themselves to appoint loyal administrators to bishoprics whose bishops were loyal to the other side, and had thus fled.[150] The Papacy confirmed several of Mayenne's choices, meaning that after his abjuration Henri found himself compelled to accept many of them, as in his treaty with the Duke of Joyeuse where he acknowledged Mayenne's choice of Anne de Murviel as bishop of Montauban.[151]

Ivry

In March 1590 the two sides met again in battle at Ivry where Mayenne was again bested. Mayenne had brought a force of 18,000 to bear against Henri's army of 13,000. The two commanders led the centre of their respective armies, with Mayenne advanced on the royalist centre, only to have his charge broken, the battle developed strongly in Henri's favour. Mayenne and the senior officers were forced to flee with whatever men they could extricate, Mayenne himself had lost his standard of Lorraine to the marquis of Rosny who presented it to the victorious Henri.[152]

This battle was far closer to Paris, and Henri, hoping to use the momentum to achieve total victory, moved south to make another attempt on the capital. Henri besieged Paris for several months, causing considerable hardship for those within the capital as food ran out. The experience radicalised further the Parisian ligue, moving it away from Mayenne and his aristocratic ligueurs.[153] Mayenne alone was unable to relieve the siege, and as such the Seize turned to Felipe for support, securing agreement for military aid in August through the threat that Paris' fall would entail a Protestant France.[154] Mayenne, in conjunction with the duke of Parma who had been dispatched from the Spanish Netherlands by Felipe joined forces at Meaux near Paris, and successfully forced Henri to abandon his siege.[146] Henri sought to bring the army to battle, but Parma avoided any attempted engagement, before returning to the Spanish Netherlands despite Mayenne's pleas for him to stay.[155] Shortly before his departure he had been with Mayenne when a deputation from the Seize came to their camp to petition Mayenne. The Seize complained about Mayenne's usurpation of their vision of the Grand Conseil and asked for the restoration of the original vision, they further protested the aristocratic direction he was taking the ligue, and asked for him to authorise a tribunal to hunt for politiques in the magistracy. They received a cold reception, Mayenne unwilling to conceded any of their demands, and some in his entourage suspecting the Seize delegation of being republicans. Shortly thereafter he rigged the Parisian elections the Seize had instituted to ensure a suitably conservative set of candidates were returned.[156]

In the wake of Cardinal Bourbon's death in captivity in 1590, the ligueur candidate for the throne became an open question. Mayenne tentatively pushed his own potential claim to the throne, though Paris preferred the young duke of Guise and Felipe pushed for Isabella Clara Eugenia his daughter with Elisabeth de Valois.[157] Looking for support for the prospect of his elevation, Mayenne dispatched Anne d'Escars the Bishop of Lisieux to Rome to inquire as to the Pope's opinion on the prospect.[158]

Barnabé Brisson and the destruction of the Seize

The ligue in Paris was frustrated by the moderate ligueur elements, and moved against Parlementaire ligueurs who they felt were insufficiently committed to the Seize program in November 1591, executing three of them, including the premier président Barnabé Brisson who they had installed as head of the Parlement only two years prior.[154] Mayenne was outraged by this affront to the noble Parlementaires and retaliated against the Seize, entering the capital on 18 November after having determined he would not be opposed in his efforts by the Spanish garrison, and ordering the execution of those who had led the campaign, and the imprisonment of members of the Seize. It was necessary for him to be sure of the Spanish, as the radical ligueurs were far closer to the Spanish than he was.[159] Other leaders of the Seize such as Bussy-Leclerc and Crucé were expelled from the city, and he took control of the Bastille[146][154][160]

Normandie had become the main theatre in which the conflict between Henri and the ligue was fought, and the two sides again met in early 1592 during the siege of Rouen. The food starved city begged Mayenne for his aid, but he was ill inclined to risk confronting the combined royal and English army that had invested the city and repeatedly assured them he would arrive soon, while putting off coming to the cities aid. On 21 April, the duke of Parma arrived and Henri was forced to lift the siege. Mayenne and Guise entered Rouen in triumph. Parma hoped to go on to crush the main royal army which was in retreat to Pont de l'Arche, but Mayenne insisted they clear the royalist controlled forts in the vicinity of Rouen.[161][162]

Estates General of 1593

In late 1592, Mayenne was pressured by the Spanish and radical ligueurs to convoke an Estates General to validate the claims of the infanta to the French throne. Mayenne was frustrated at the requests, and bemoaned to the prévôt des marchands of Paris 'what more do you people want?'[163] He would however, reluctantly accept, and 128 deputies gathered in Paris. Among the deputies were thirteen bishops, of whom Mayenne had personally appointed three.[164] This was far fewer deputies than had convened in the previous estates, however royal troops prevented many delegates from making it to Paris.[119] Mayenne delivered the opening address stressing the importance of finding a Catholic king for France. Henri for his part did not recognise the validity of the Estates, however he attempted to open a line of communication with the moderate elements of the body. The radicals in the ligue were horrified, but the body as a whole accepted, and a ten-day truce was produced by the dialogue, after talks at Suresnes. The Seize denounced the talks, while Mayenne for his part had chosen delegates to participate in them.[165]

On 17 May Henri announced his plan to convert to Catholicism, throwing the Estates into chaos.[166] At the estates the Spanish were increasingly alienating all but the most diehard ligueurs with their proposals, including on 28 May a proposal that Felipe's daughter the Infanta marry Ernst von Hapsburg, and that the new couple would become king and queen. The estates baulked at the idea of two foreigners ruling them with only hardcore elements of the Seize sympathetic. The Spanish tried again in early July, proposing a marriage between the Infanta and the young duke of Guise, however the moment was gone and this loss of momentum was sealed with Henri's attendance of mass at Saint-Denis on 25 July.[167] Mayenne and his other relatives, despite their kinship with the young duke of Guise, and his popularity among the urban ligue were little interested in this proposal either. Mayenne was underwhelmed by the young duke, and moreover had tasted enough power himself that he was ill inclined to surrender it to his nephew. His wife crudely described the young duke as 'a little boy, who still needed a spanking'.[168]

Mayenne for his part had sought to reconfigure the estates, proposing the creation of a fourth estate for the magistracy in May, however this was shot down by the existing estates.[165]

Guillaume du Vair and Le Maistre, two moderate ligueur Parlementaires, who had walked out of the estates after the Spanish proposal engineered a decree the Parlement declaring that no foreign prince could become king of France, earning rebukes from both the Seize and Mayenne.[169] The ten day truce that had been agreed in April, bloomed into a larger truce agreed between Mayenne and Henri on 31 July 1593.[170]

By 1593 the radical urban ligueurs were fundamentally disillusioned with Mayenne and the other noble ligueurs. In pamphlets some proposed abolishing hereditary nobility, and were hurt that Mayenne opposed the candidature of the duke of Guise for election to the French throne.[171] The pamphlet Le Dialogue d'entre le Maheustre et le Manant, written by the exiled Crucé, bitterly denounced Mayenne and the other politique ligueurs. Mayenne was furious and had the book condemned by the Parlement, and the ligueur printers who had published it imprisoned. He refused to release the imprisoned men, despite the pleas of both the Spanish ambassador and Papal Legate.[172]

Truce

The truce of July 1593, was extended, such that it only expired in early 1594. Mayenne was faced with growing weariness from the cities still loyal to him in Bourgogne, who exploded in anger at his agents both due to the resumption of war, and the particular harshness of the winter.[173]

The war was becoming increasingly dire for Mayenne and the ligue, he reacted apoplectically when word reached the capital that nearby Meaux had surrendered to Henri, allegedly tearing the letter bearing the news apart with his teeth.[172] Henri used the capture as a further opportunity to push his charm offensive strategy for Paris, highlighting how well he had treated the city that had surrendered to him.[174] During February, Lyon and Orléans fell to Henri, and Mayenne was increasingly pressured by radicals in the capital to respond to the deterioration. He was urged to expel suspected hundreds of suspected politiques from the city, and to install a Spanish garrison of 10,000 men. Mayenne responded that he would support the latter, if the Spanish paid for it.[175]

Paris falls

Mayenne departed the capital on 6 March 1594 with his family, and Henri moved to enter Paris on 22 March with the support of the turncoat governor of the city, Brissac.[176] The new regime consolidated their authority quickly. Over 100 unrepentant Mayenne supporters were exiled from the capital.[177] On 30 March, the Paris Parlement revoked all laws passed since 29 December 1588, and annulled his authority as lieutenant-general. Anyone who obeyed his commands was declared to be guilty of lèse majesté.[178] Membership of the ligue was also outlawed and the only processions would be those of the Parlementaires, to commemorate the return of Paris to royal obedience.[179]

Mayenne and Guise met with the lieutenant-general of Champagne, Saint-Paul at Bar-le-Duc in April 1594. Suspicions by this point ran deep on each side that the other was planning to sell them out and defect to Henri. Saint-Paul was denied access to several meetings between Mayenne and the duke of Lorraine, and resultingly decided he was no longer interested in meeting with Mayenne, and set off back to Reims. Guise and Mayenne followed him, arriving outside Reims ahead of him, only to find themselves refused entry. By this time Saint-Paul had reached agreement with Henri, and was just waiting for money for his war against Henri to arrive from Spain, before selling out the ligue. On 24 April, having been afforded entry, Guise would murder Saint-Paul after an argument.[180] Mayenne then departed for Soissons, leaving Reims in the hands of Guise.[181]

During the summer of 1594, Mayenne cajoled Spain into providing another army to support him, using his control of Bourgogne as his last remaining leverage of relevance. Philip II obliged and dispatched a force under Karl von Mansfeld. Together the two harried Henri as he attempted to besiege Laon, refusing to give battle and vexing Henri. By July the garrison of Laon capitulated to Henri, and his hands were freed, causing Mayenne to retreat into his heartland of Bourgogne.[182]

Fontaine-Française

Increasingly in control of the kingdom by 1595, Henri outlined a broad plan of attack for his subordinates. the duke of Biron was to head into Bourgogne and crush Mayenne there.[183] By this point most of Mayenne's clients in Bourgogne had abandoned him, however as Henri had not yet received full absolution from the Pope, Mayenne had chosen to continue the fight.[184] Biron had great success, seizing Autun and Beaune from Mayenne, he then moved into Dijon, occupying the city proper, but struggling to reduce the citadel.[185] Mayenne's decision to continue the fight now cost him dearly, as on 20 April, Henri awarded the governorship of Bourgogne to Biron.[184]

The Spanish commander Don Velasco invaded Bourgogne himself, to save Dijon. He linked up with Mayenne and the two advanced up the Saône. A portion of the royal army under Henri stumbled into them at Fontaine-Française, though severely outnumbered the royalists gave battle. Mayenne recognised Henri's helmet on the field and attempted a massed cavalry charge, but was repulsed by new French units entering the field. Mayenne urged Velasco to bring up the rest of the Spanish forces and overwhelm Henri's position but Velasco was cautious, suspecting Henri's force was far larger than it really was, and resultingly he withdrew his forces from the field.[186]

Edict of Folembray

After the embarrassment of Fontaine-Française, and Velasco's refusal to commit more resources to the remaining ligueur strongholds in Bourgogne, Mayenne withdrew from the Spanish camp in disgust.[187] Mayenne entered serious talks for his reconciliation with the crown shortly thereafter.[183] His return to submission to the crown was in part facilitated by Zamet, the formerly ligueur banker who had joined Henri after his abjuration.[95] In the Edict of Folembray of September 1595 that re-secured his loyalty he was granted three surety towns (Chalon, Seurre and Soissons) for a period of 6 years, the governorship of the Île de France (but without control over Paris, Melun or Saint-Denis) and a bribe of 900,000 écus.[188][183] Despite these sizeable concessions, Mayenne was detached by this edict from his power base and clientèle networks in Bourgogne, the governorship of that province having been given to Biron that April.[189] Moreover, his governorship was little more than a figleaf for his dignity, denied as it was, the major settlements inside its bounds.[190] As part of his reconciliation with Henri, he was acquitted of having played any role in the death of Henri III, and the Parlements were forbidden to pursue any cases against him or other ligueurs over the murder.[191] This last provision greatly upset Louise de Lorraine, Henri's widow, who had been campaigning that justice be done for the murder of her husband.[192]

His return to the royalist camp, came in great part due to the fact that the ligueur cause was increasingly a lost one, and if he wished to preserve his titles and landed influence, some form of accommodation was the only way to facilitate this.[193]

He gave his formal submission to Henri in January 1596, kneeling before the king and denouncing the Spanish and Italian ruses that had led him astray from his true king. Henri embraced him as a courageous and well meaning man, and the two went for a tour of the Château gardens. Henri walked at a demanding pace, leaving Mayenne red faced and out of breath. Mayenne complained to Henri who remarked to him that this would be the only vengeance he ever got against his cousin.[192]

Now a royalist, Mayenne worked to bring over his last remaining kin who fought on in France, his distant cousin Mercœur.[194] Mayenne proposed to the king's mistress, Gabrielle d'Estrées a marriage between her son, and Mercœur's daughter, Françoise de Lorraine. She was open to the idea, it affording her the potential of the Penthièvre inheritance, and she was able to secure the match.[195]

Amiens

The war was by now almost entirely directed against Spain, the internal conflict having ceased. Philip II had taken the opportunity of the chaos of the last few years to seize or buy a number of cities in north eastern France, among them Amiens. In mid 1597, Henri laid siege to Amiens. He found himself unable to rely on his former Protestant co-religionists, who were so disillusioned with him by 1597 that they withdrew their forces from his army. Instead his siege was led by Catholic notables, among them his former enemy Mayenne.[196] Mayenne was delighted to have an opportunity to demonstrate his skills as a strategist to Henri.[197] In an odd twist, Mayenne was now fighting against his cousin, Aumale who fought for the Spanish at Amiens, having resisted all offers from Henri and resultingly becoming a Spanish agent.[198] The royal army entered Amiens on 25 September, and Henri was delighted at the performance of his army.[199]

Edict of Nantes

When in 1598, Henri promulgated the famous Edict of Nantes, exceptions were carved out from the edict for those cities and towns that had been granted to the principal former ligueurs including Mayenne, to ensure they would not have to permit Protestantism in their territories.[200] The edict ran into vociferous objections from many quarters, and in December 1598, Henri reviewed the edict in council. In response to criticisms that Protestants were allowed to access high offices, Henri highlighted that he allowed his former enemies, the ligueurs in high authority, he could not reasonably deny the Protestants who had supported him high office. Mayenne who was present at the council, did not object to this argument.[201] He would later be approached by militant Catholics who asked him to overturn the edict, however Mayenne, now a royalist, refused their requests.[194]

As a reward for his loyalty, in 1599, Henri erected the duchy of Aiguillon from the queen's lands for his eldest son, citing the services given to him by Mayenne as a reason for his decision. Marguerite was greatly upset that her lands were being requisitioned to reward the son of a former rebel and succeeded in convincing her husband to annual the young Mayenne's judicial rights over the duchy[14]

Death

Having attended Henri's royal council more frequently in the early years of his uncontested reign, Mayenne faded from attendance as the years wore on.[202] Neither he nor his nephew Guise would threaten the monarchy in the following decade.[203] Mayenne died in 1611 at Soissons, and was succeeded as duke of Mayenne by his son Henri.[204]

See also

- Love's Labour's Lost - Charles served as the basis for the character of Dumaine in the play.[205]

Sources

- d'Aubigné, Agrippa (1995). Thierry, André (ed.). Histoire universelle: 1594-1602 (in French). Librairie Droz S.A.

- Babelon, Jean-Pierre (2009). Henri IV. Fayard.

- Baumgartner, Frederic (1986). Change and Continuity in the French Episcopate: The Bishops and the Wars of Religion 1547-1610.

- Bayard, Marc (2010). Rome-Paris 1640: transferts culturels et renaissance d'un centre artistique (in French). Somogy.

- Benedict, Philip (2003). Rouen during the Wars of Religion. Cambridge University Press.

- Bernstein, Hilary (2004). Between Crown and Community: Politics and Civic Culture in Sixteenth-Century Poitiers. Cornell University Press.

- Boltanski, Ariane (2006). Les ducs de Nevers et l'État royal: genèse d'un compromis (ca 1550 - ca 1600) (in French). Librairie Droz.

- Carroll, Stuart (2005). Noble Power During the French Wars of Religion: The Guise Affinity and the Catholic Cause in Normandy. Cambridge University Press.

- Carroll, Stuart (2011). Martyrs and Murderers: The Guise Family and the Making of Europe. Oxford University Press.

- Chevallier, Pierre (1985). Henri III: Roi Shakespearien. Fayard.

- Cloulas, Ivan (1979). Catherine de Médicis. Fayard.

- Durot, Éric (2012). François de Lorraine, duc de Guise entre Dieu et le Roi. Classiques Garnier.

- Harding, Robert (1978). Anatomy of a Power Elite: the Provincial Governors in Early Modern France. Yale University Press.

- Heller, Henry (2003). Anti-Italianism in Sixteenth Century France. University of Toronto Press.

- Hibbard, G.R., ed. (1990). Love's Labour's Lost. Oxford University Press.

- Holt, Mack (2002). The Duke of Anjou and the Politique Struggle During the Wars of Religion. Cambridge University Press.

- Holt, Mack P. (2005). The French Wars of Religion, 1562-1629. Cambridge University Press.

- Holt, Mack P. (2020). The Politics of Wine in Early Modern France: Religion and Popular Culture in Burgundy, 1477-1630. Cambridge University Press.

- Jouanna, Arlette (1998). Histoire et Dictionnaire des Guerres de Religion. Bouquins.

- Knecht, Robert (2010). The French Wars of Religion, 1559-1598. Routledge.

- Knecht, Robert (2014). Catherine de' Medici. Routledge.

- Knecht, Robert (2016). Hero or Tyrant? Henry III, King of France, 1574-1589. Routledge.

- Konnert, Mark (1997). Civic Agendas & Religious Passion: Châlon-sur-Marne during the French Wars of Religion 1560-1594. Sixteenth Century Journal Publishers Inc.

- Konnert, Mark (2006). Local Politics in the French Wars of Religion: The Towns of Champagne, the Duc de Guise and the Catholic League 1560-1595. Ashgate.

- Pitts, Vincent (2012). Henri IV of France: His Reign and Age. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Roberts, Penny (1996). A City in Conflict: Troyes during the French Wars of Religion. Manchester University Press.

- Roberts, Penny (2013). Peace and Authority during the French Religious Wars c.1560-1600. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Roelker, Nancy (1996). One King, One Faith: The Parlement of Paris and the Religious Reformation of the Sixteenth Century. University of California Press.

- Le Roux, Nicolas (2000). La Faveur du Roi: Mignons et Courtisans au Temps des Derniers Valois. Champ Vallon.

- Salmon, J.H.M (1979). Society in Crisis: France during the Sixteenth Century. Metheun & Co.

- Sutherland, Nicola (1980). The Huguenot Struggle for Recognition. Yale University Press.

- Williams, George L. (1998). Papal Genealogy: The Families and Descendants of the Popes. McFarland & Company, Inc.

- Wood, James (2002). The Kings Army: Warfare, Soldiers and Society during the Wars of Religion in France, 1562-1576. Cambridge University Press.

References

- ↑ Knecht 2010, p. 160.

- ↑ Carroll 2011, p. 311.

- ↑ Durot 2012, p. 289.

- ↑ Harding 1978, p. 113.

- ↑ Carroll 2005, p. 28.

- ↑ Carroll 2011, p. 224.

- ↑ Carroll 2011, p. 221.

- ↑ Bayard 2010, p. 117.

- ↑ Boltanski 2006, p. 501.

- ↑ d'Aubigné 1995, p. 33-34.

- ↑ Williams 1998, p. 66.

- ↑ Babelon 2009, p. 652.

- 1 2 3 Carroll 2011, p. 223.

- 1 2 Jouanna 1998, p. 1092.

- 1 2 3 Knecht 2016, p. 282.

- ↑ Salmon 1979, p. 246.

- ↑ Le Roux 2000, p. 51.

- ↑ Le Roux 2000, p. 193.

- ↑ Bernstein 2004, p. 158.

- ↑ Holt 2002, p. 12.

- ↑ Carroll 2011, p. 188.

- ↑ Sutherland 1980, p. 192.

- ↑ Carroll 2011, p. 200.

- 1 2 Carroll 2011, p. 201.

- ↑ Knecht 2014, p. 142.

- ↑ Jouanna 1998, p. 1088.

- ↑ Carroll 2011, p. 202.

- ↑ Wood 2002, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Le Roux 2000, p. 133.

- ↑ Holt 2005, p. 148.

- ↑ Harding 1978, p. 221.

- ↑ Holt 2020, p. 170.

- 1 2 Jouanna 1998, p. 1089.

- ↑ Le Roux 2000, p. 150.

- ↑ Le Roux 2000, p. 155, 429.

- ↑ Le Roux 2000, p. 156.

- ↑ Harding 1978, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Harding 1978, p. 13.

- ↑ Harding 1978, p. 123.

- ↑ Holt 2020, p. 165.

- ↑ Le Roux 2000, p. 176.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 108.

- ↑ Wood 2002, p. 36.

- ↑ Knecht 2010, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Le Roux 2000, p. 374.

- ↑ Sutherland 1980, p. 267.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 156.

- ↑ Le Roux 2000, p. 333.

- ↑ Holt 2002, pp. 88–92.

- ↑ Cloulas 1979, p. 414.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 166.

- ↑ Carroll 2005, pp. 174–175.

- ↑ Le Roux 2000, p. 426.

- ↑ Jouanna 1998, p. 310.

- ↑ Jouanna 1998, p. 290.

- ↑ Le Roux 2000, p. 319.

- ↑ Carroll 2005, p. 187.

- ↑ Carroll 2005, p. 192.

- ↑ Knecht 2010, p. 67.

- ↑ Konnert 1997, p. 134.

- ↑ Konnert 2006, p. 162.

- ↑ Holt 2005, p. 124.

- ↑ Baumgartner 1986, p. 158.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 232.

- ↑ Carroll 2011, pp. 256–257.

- ↑ Carroll 2011, p. 257.

- ↑ Knecht 2010, p. 68.

- ↑ Konnert 2006, p. 177.

- ↑ Konnert 2006, p. 187.

- ↑ Le Roux 2000, p. 587.

- ↑ Knecht 2010, p. 69.

- ↑ Carroll 2011, p. 262.

- ↑ Carroll 2011, p. 264.

- ↑ Carroll 2011, p. 265.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 240.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 241.

- ↑ Knecht 2014, p. 263.

- ↑ Cloulas 1979, p. 587.

- ↑ Roelker 1996, p. 385.

- 1 2 Salmon 1979, p. 252.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 258.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 260, 263.

- ↑ Knecht 2014, p. 265.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 269.

- ↑ Salmon 1979, p. 245.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 287.

- ↑ Salmon 1979, p. 251.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 278.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 281.

- ↑ Knecht 2010, p. 72.

- ↑ Roelker 1996, p. 378.

- ↑ Holt 2005, p. 134.

- ↑ Knecht 2010, p. 91.

- ↑ Bernstein 2004, pp. 230–231.

- 1 2 Heller 2003, p. 201.

- ↑ Cloulas 1979, p. 331.

- ↑ Salmon 1979, p. 255.

- ↑ Le Roux 2000, p. 692.

- ↑ Roberts 1996, p. 174.

- ↑ Holt 2005, p. 144.

- ↑ Benedict 2003, p. 188.

- ↑ Benedict 2003, p. 187.

- ↑ Benedict 2003, p. 209.

- 1 2 Benedict 2003, p. 216.

- ↑ Harding 1978, p. 106.

- ↑ Carroll 2005, p. 243.

- ↑ Holt 2005, p. 147.

- ↑ Harding 1978, p. 92.

- ↑ Roberts 1996, p. 175.

- ↑ Bernstein 2004, p. 221, 229.

- ↑ Bernstein 2004, p. 220.

- ↑ Roberts 1996, p. 181.

- ↑ Konnert 2006, p. 209.

- ↑ Konnert 2006, p. 33, 209.

- ↑ Konnert 2006, p. 210.

- ↑ Holt 2020, p. 171.

- ↑ Holt 2005, pp. 148–149.

- 1 2 Salmon 1979, p. 264.

- 1 2 Holt 2005, p. 150.

- ↑ Harding 1978, p. 98.

- ↑ Holt 2020, p. 173.

- 1 2 Jouanna 1998, p. 377.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 283.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 289.

- ↑ Sutherland 1980, p. 366.

- ↑ Bernstein 2004, p. 202.

- ↑ Pitts 2012, p. 141.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 291.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 298.

- ↑ Carroll 2005, p. 227.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 292.

- ↑ Konnert 1997, p. 153.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 296.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 293.

- ↑ Holt 2005, p. 135.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 297.

- ↑ Konnert 2006, p. 227.

- ↑ Le Roux 2000, p. 705.

- ↑ Bernstein 2004, p. 187.

- ↑ Bernstein 2004, p. 239.

- ↑ Bernstein 2004, p. 242.

- ↑ Bernstein 2004, p. 243.

- ↑ Bernstein 2004, p. 245.

- ↑ Bernstein 2004, p. 229.

- ↑ Bernstein 2004, p. 230.

- 1 2 3 Knecht 2010, p. 79.

- ↑ Salmon 1979, p. 259.

- ↑ Jouanna 1998, p. 356.

- ↑ Baumgartner 1986, p. 171.

- ↑ Baumgartner 1986, p. 175.

- ↑ Baumgartner 1986, p. 183.

- ↑ Pitts 2012, pp. 152–153.

- ↑ Holt 2005, p. 140.

- 1 2 3 Holt 2005, p. 141.

- ↑ Salmon 1979, p. 261.

- ↑ Salmon 1979, p. 265.

- ↑ Knecht 2010, p. 77.

- ↑ Baumgartner 1986, p. 173.

- ↑ Salmon 1979, p. 266.

- ↑ Roelker 1996, p. 392.

- ↑ Benedict 2003, p. 221.

- ↑ Pitts 2012, p. 164.

- ↑ Roelker 1996, p. 400.

- ↑ Baumgartner 1986, p. 176.

- 1 2 Salmon 1979, p. 268.

- ↑ Knecht 2010, p. 80.

- ↑ Salmon 1979, pp. 269–270.

- ↑ Carroll 2011, p. 298.

- ↑ Holt 2005, p. 151.

- ↑ Konnert 2006, p. 244.

- ↑ Knecht 2010, p. 78.

- 1 2 Roelker 1996, p. 416.

- ↑ Jouanna 1998, p. 401.

- ↑ Roelker 1996, p. 417.

- ↑ Roelker 1996, p. 424.

- ↑ Roelker 1996, p. 421, 429.

- ↑ Salmon 1979, p. 272.

- ↑ Roelker 1996, p. 435.

- ↑ Roelker 1996, p. 436.

- ↑ Konnert 2006, p. 247.

- ↑ Konnert 2006, p. 248.

- ↑ Pitts 2012, p. 186.

- 1 2 3 Salmon 1979, p. 293.

- 1 2 Holt 2020, p. 235.

- ↑ Pitts 2012, p. 194.

- ↑ Pitts 2012, pp. 194=195.

- ↑ Pitts 2012, p. 195.

- ↑ Jouanna 1998, p. 398.

- ↑ Pitts 2012, p. 240.

- ↑ Holt 2020, p. 236.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 313.

- 1 2 Pitts 2012, p. 196.

- ↑ Roelker 1996, p. 393.

- 1 2 Holt 2020, p. 237.

- ↑ Babelon 2009, pp. 648–649.

- ↑ Pitts 2012, p. 201.

- ↑ Babelon 2009, p. 621.

- ↑ Carroll 2005, p. 247.

- ↑ Pitts 2012, p. 202.

- ↑ Roberts 2013, p. 152.

- ↑ Pitts 2012, p. 213.

- ↑ Babelon 2009, p. 711.

- ↑ Babelon 2009, p. 887.

- ↑ Jouanna 1998, p. 1088, 1503.

- ↑ Hibbard 1990, p. 49.