| Cheadle Hulme | |

|---|---|

The cenotaph, on the corner of Ravenoak Road and Manor Road | |

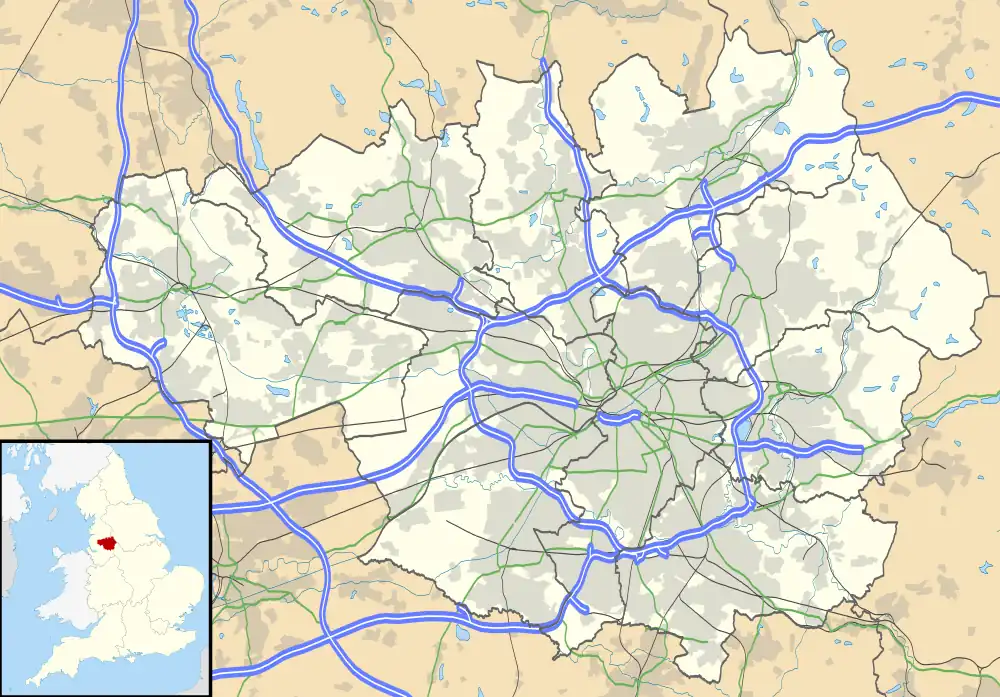

Cheadle Hulme Location within Greater Manchester | |

| Area | 8.37 km2 (3.23 sq mi) |

| Population | 26,479 (2011)[1][2] |

| • Density | 3,164/km2 (8,190/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | SJ872870 |

| • London | 157 mi (253 km) SE |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | CHEADLE |

| Postcode district | SK8 |

| Dialling code | 0161 |

| Police | Greater Manchester |

| Fire | Greater Manchester |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

Cheadle Hulme (/ˌtʃiːdəl ˈhjuːm/) is a suburb in the Metropolitan Borough of Stockport, Greater Manchester, England,.[3] Historically in Cheshire, it is 2 miles (3.2 km) south-west of Stockport and 8 miles (12.9 km) south-east of Manchester. It lies in the Ladybrook Valley, on the Cheshire Plain, and the drift consists mostly of boulder clay, sands and gravels. In 2011, it had a population of 26,479.[4][5]

Evidence of Bronze Age, Roman and Anglo-Saxon activity, including coins, jewellery and axes, have been discovered locally. The area was first mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086 when it was a large estate which included neighbouring Cheadle. In the early 14th century, it was split into southern and northern parts at about the future locations of Cheadle Hulme and Cheadle respectively. The area was acquired by the Moseley family in the 17th century and became known as Cheadle Moseley. Unlike many English villages, it did not grow around a church; instead it formed from several hamlets, many of which retain their names as neighbourhoods within Cheadle Hulme. In the late 19th century, Cheadle Hulme was united with Cheadle, Gatley and other neighbouring places to form the urban district of Cheadle and Gatley. This district was abolished in 1974 and Cheadle Hulme became a part of the Metropolitan Borough of Stockport.

Cheadle Hulme has good transport links, with its own railway station and is in close proximity to Manchester Airport, the M60 motorway and the A34 road.

History

Early history

The Domesday Book provides the earliest mention of the area, where it is recorded as "Cedde", Celtic for "wood".[6] Local archaeological finds include Bronze Age axes discovered in Cheadle. Evidence of Roman occupation includes coins and jewellery, which were found in 1972,[7] and the modern-day Cheadle Road, originally known as Street Lane, may be of Roman origin. A stone cross dedicated to the Anglo-Saxon St Chad, uncovered in 1873, indicates Anglo-Saxon activity.[8] The cross was found in an area called "Chad Hill", on the banks of Micker Brook near its confluence with the River Mersey; this area became "Chedle".[6][7] Suggestions for the origin of the name include the words cedde, and leigh or leah, in Old English meaning "clearing", forming the modern day "Cheadle".[9] "Hulme" may have been derived from the Old Norse word for "water meadow" or "island in the fen".[10][11]

According to the Domesday Book in 1086, the modern-day Cheadle and Cheadle Hulme were a single large estate. Valued at £20,[12] it was described as "large and important" and "a wood three leagues (about 9 miles (14 km)) long and half as broad".[8] One of the earliest owners of the property was the Earl of Chester. It was held by a Gamel, a free Saxon, under Hugh d'Avranches, 1st Earl of Chester, and later became the property of the de Chedle family, who took their name from the land they owned.[13] By June 1294 Geoffrey de Chedle was Lord of the Manor.[8] Geoffrey's descendant Robert (or Roger) died in the early 1320s, leaving the estate to his wife Matilda who held it until her death in 1326.[8] As there were no male heirs the manor, which was now worth £30 per annum,[14] was divided between her daughters, Clemence and Agnes.[15] Clemence inherited the southern half (which would later become the modern-day Cheadle Hulme), and Agnes inherited the northern half (latterly Cheadle).[12] The two areas became known as "Chedle Holme" and "Chedle Bulkeley" respectively.[16] Shortly afterwards the Chedle Holme estate was divided and the part where Hulme Hall is now situated became known as "Holme", and held by the Vernons. The estates were reunified on the death of the last of the Vernons in 1476.[15]

The only daughter of Clemence and William de Bagulegh, Isabel de Bagulegh, succeeded her parents as owner of the manor, and married Sir Thomas Danyers. Danyers was rewarded for his efforts in the crusades through an annual payment from the King of 40 marks, as well as the gift of Lyme Hall. His daughter Margaret continued to receive payments after his death.[16]

The first John Savage succeeded Margaret, and nine more followed him.[17] The tenth died young, so the estate passed to his brother, Thomas Savage. In 1626 Charles I created the title of Viscount Savage for him.[18] On his death the estate passed to his daughter Joan, who later married John Paulet, 5th Marquess of Winchester. Joan died during childbirth at the age of 23, and the estate passed to the Marquess. The Marquess practised Catholicism, and in 1643 the estate was confiscated due to persecution of Catholics in the English Civil War.[12]

Following this, the estate was acquired by the Moseley family of Manchester and became known as Cheadle Moseley. Anne Moseley was the last of this family to hold the manor, as her husband could not afford to keep it following her death. It was purchased by John Davenport, who bequeathed it to the Bamford family when he died childless in 1760. After the last Bamford died without male issue in 1806, the estate passed to Robert Hesketh who took the name Bamford-Hesketh;[12] it is from this family that the Hesketh Tavern public house in Cheadle Hulme got its name.[19] The last person to hold the manor was Winifred, Countess of Dundonald, one of Bamford-Hesketh's descendants.[12]

Modern history

Prior to 1868, Cheadle Moseley was a township within the ancient parish of Cheadle. Its population more than doubled during the first half of the 19th century, rising from 971 in 1801 to 2,319 in 1851. Cheadle Moseley became a civil parish in 1868. In 1879, it was merged with neighbouring Cheadle Bulkeley to form the civil parish of Cheadle.[20][21] Cheadle parish went on to become part of the newly formed Cheadle and Gatley district in 1894.[22] The name "Cheadle Moseley" continued to be used for the area, and appeared on tithes and deeds until the 20th century.[12] In 1974, the Cheadle and Gatley district was abolished and Cheadle Hulme became part of the Metropolitan Borough of Stockport.[3]

RAF Handforth was a large and important storage facility that contributed directly to the war effort. The site stretched from the centre of Handforth village, through Cheadle Hulme and onwards to Woodford. The industrial estate Adlington Park in Woodford/Poynton was a dispersed site of RAF Handforth. Cheadle Hulme itself escaped being badly damaged, but its villagers knew the extent of the war, mainly due to the large and visible presence of the RAF and could hear the sounds of air-raids on Manchester.[23]

Cheadle Hulme did not grow around a church like many English villages, but instead grew from several hamlets that existed in the area. Many of the names of these hamlets still appear in the names of areas, including Smithy Green, Lane End, Gill Bent, and Grove Lane.[19] Some of the many farms such as Orish Mere Farm and Hursthead Farm which covered the area also retain their names in schools that were built in their place.[24]

The area was struck by an F1/T2 tornado on 23 November 1981, as part of the record-breaking nationwide tornado outbreak on that day.[25][26]

Governance

Cheadle Hulme was historically part of the ancient parish of Cheadle within the historic county boundaries of Cheshire. It formed the township of Cheadle Moseley. Following the Municipal Corporations Act 1835, part of Cheadle Moseley was amalgamated into the Municipal Borough of Stockport.[3] Cheadle Moseley became a separate civil parish in 1866, but in 1879 it was united with the neighbouring civil parish of Cheadle Bulkeley to form the civil parish of Cheadle.[27]

Established in 1886, Cheadle Hulme's first local authority was the Cheadle and Gatley local board of health, a regulatory body responsible for standards of hygiene and sanitation for the area of Stockport Etchells township and the part of Cheadle township outside the Municipal Borough of Stockport. The board of health was also part of Stockport poor law union. In 1888 the board was divided into four wards: Adswood, Cheadle, Cheadle Hulme and Gatley.[28] Under the Local Government Act 1894 the area of the local board became Cheadle and Gatley Urban District. There were exchanges of land with the neighbouring urban districts of Wilmslow and Handforth in 1901, and the wards were restructured again, splitting Cheadle Hulme into north and south, and merging in Adswood.[28] Due to the fast-paced growth of the district, the wards were again restructured in 1930, with the addition of Heald Green. In 1940 the current wards of Adswood, Cheadle East, Cheadle West, Cheadle Hulme North, Cheadle Hulme South, Gatley and Heald Green were established.[29] Under the Local Government Act 1972 the Cheadle and Gatley Urban District was abolished, and Cheadle Hulme has, since 1 April 1974, formed an unparished area of the Metropolitan Borough of Stockport within the metropolitan county of Greater Manchester.[3]

Since 1950 Cheadle Hulme has been part of the Cheadle parliamentary constituency,[30] and has been represented by Conservative member Mary Robinson since 2015.[31] Six councillors, three representing Cheadle Hulme South ward and three representing Cheadle Hulme North, serve on the borough council.[32]

Geography

At 53°22′34″N 2°11′17″W / 53.376°N 2.188°W, Cheadle Hulme is in the south of Greater Manchester. Stockport Metropolitan Borough straddles the Cheshire Plain and the Pennines, and Cheadle Hulme is in the west of the borough on the Cheshire Plain. The area lies in the Ladybrook Valley next to the Micker Brook, a tributary of the River Mersey which flows north–west from Poynton through Bramhall and Cheadle Hulme, joining the Mersey in Stockport.[33]

The majority of buildings in the area are houses from the 20th century, but there are a few buildings, landmarks, and objects that date from the 16th century, in addition to Bramall Hall which dates from the 14th century. In particular, there are many Victorian buildings in several places across the area. The local drift geology is mostly glacial boulder clay, as well as glacial sands and gravel. For many years the clay has been used for making bricks and tiles.[34]

Cheadle Hulme's climate is generally temperate, like the rest of Greater Manchester. The mean highest and lowest temperatures of 13.2 °C (55.8 °F) and 6.4 °C (43.5 °F) are slightly above the average for England, while the annual rainfall of 806.6 millimetres (31.76 in) and average hours (1,394.5 hours) of sunshine are respectively above and below the national averages.[35][36]

Demography

- Note: Cheadle Hulme is split into two areas for censuses, Cheadle Hulme North and Cheadle Hulme South. The figures below before 2011 account for both areas. From 2011 the numbers are based on the data for the Cheadle Hulme Built-up area sub division as published by the Office for National Statistics. The data for this area do not match the combined total for the Cheadle North and South wards as the boundaries for this sub-division are slightly different.

| Cheadle Hulme compared | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 UK census | Cheadle Hulme | Stockport (borough)[37] | England[38] |

| Total population | 24,362 | 283,275 | 53,012,456 |

| White | 91.6% | 92.1% | 85.4% |

| Asian | 5.5% | 4.9% | 7.8% |

| Mixed | 1.5% | 1.8% | 2.3% |

| Black | 0.6% | 0.7% | 3.5% |

| Other | 0.8% | 0.6% | 1.0% |

According to the Office for National Statistics, Cheadle Hulme had a population of 24,362 at the 2011 census.[39] The population density was 4,152 inhabitants per square kilometre (10,754/sq mi),[39] with a 100–95.3 female-to-male ratio. Of those aged over 16, 25.0% were single (never married or registered a same-sex civil partnership), 58.1% married and 0.1% in a registered same-sex civil partnership[39] Cheadle Hulme's 9,962 households included 26.1% one-person, 42.9% Married or same-sex civil partnership couples living together, 6.2% were co-habiting couples, and 8.3% single parents with children.[39] Of those aged 16–74, 13.1% had no academic qualifications.[39]

About 66.6% of Cheadle Hulme's residents reported themselves as being Christian, 3.4% Muslim, 1.2% Hindu, 0.6% Jewish, 0.3% Buddhist and 0.1% Sikh. The census recorded 21.1% as having no religion, 0.4% had an alternative religion and 6.3% did not state their religion.[39]

| Population growth in Cheadle Moseley (from 1664 to 1971)[40] | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1664 | 1801 | 1811 | 1821 | 1831 | 1841 | 1851 | 1861 | 1871 | 1891 | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1939 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 |

| Population | 390 | 971 | 1,296 | 1,534 | 1,946 | 2,288 | 2,319 | 2,329 | 2,612 | 8,252 | 7,916 | 9,913 | 11,036 | 18,473 | 32,245 | 31,511 | 45,621 | 60,807 |

| Urban District 1981–1971[41] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Population growth in Cheadle and Gatley (including Cheadle Hulme) from 1891 to 2001 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 |

| Population | 59,828 | 58,457 | 57,507 |

| Urban Subdivision 1981–2001[42][43][44] | |||

| Population growth in Cheadle Hulme (north and south) from 2011 | |

|---|---|

| Year | 2011 |

| Population | 24,362 |

| • Cheadle Hulme Built-up area sub division 2011[39] | |

Economy

For many years Cheadle Hulme was rural countryside,[45] made up of woods, open land, and farms. The local population was made up of farmers and peasants, living in small cottages and working the land under the tenancy of the Lord of the Manor.[46] Most families kept animals for food, grew their own crops,[45] and probably bought and sold produce at Stockport market.[46] Water was obtained from local wells and ponds, and sometimes the Micker Brook.[47]

Local silk weaving became a large part of everyday life. The work took place in domestic cottages in a room known as a "loomshop",[45] and the woven silk was transported to firms in Macclesfield 8 miles (13 km) away.[48] Silk-weaving remained commonplace in the area until the early 20th century, when the process became industrialised.[45] Other industries in the area included a corn mill, which collapsed some time during the First World War, located next to the Micker Brook; cotton weaving; and brickworks, one located where the fire station is and one near the railway station.[49] A coal wharf was situated opposite the railway station and supplied the area with coal.[50]

The building of the railways in the early 1840s introduced new employment opportunities for people in places such as Stockport and Manchester, as well as an influx of people coming to live in the area.[47][51] In the mid-19th century, one of the earliest shops was opened in the Smithy Green area, selling groceries, sweets and other provisions.[45] As people settled in the area, more shops were opened and new houses were built, many of which still stand.[49] During the early 20th century Cheadle Hulme experienced a rapid growth in population, mostly due to an influx of people from Manchester and other large towns and cities coming to live in the area, and it gradually became more suburban.[52] In the 1930s more houses were built around the Grove Lane and Pingate Lane, Gill Bent Road, Hulme Hall Road and Cheadle Road areas, and new roads replaced old farms.[23][53] In the 1960s the Hursthead estate was built on land that was once Hursthead Farm.[54] By 2009 the only farm remaining was Leather's Farm on Ladybridge Road.[55]

Cheadle Hulme is served by a fire station on Turves Road which opened in October 1960. Before this the area made use of a service in Cheadle.[56] An ambulance station is near the fire station, and the closest public hospital is Stepping Hill Hospital in Hazel Grove. Until the early 2000s the area had a police station which served as the headquarters for the west Stockport area.[57] The building, which opened in 1912, was sold in 2006 and converted into flats.[58]

Cheadle Hulme has a large variety of businesses serving the area. Station Road is home to the shopping precinct (built in 1962)[59] and contains among other businesses an Oxfam shop, an Asda supermarket, a hairdressing salon, an optician, a pharmacy, some clothing retailers and several restaurants. There are more restaurants and cafés along Station Road as well as solicitors and building societies, and long-running family businesses such as Pimlott's butchers are also prominent.[60] In 2002, a Tesco Express opened on the site of an old petrol station, and in July 2007 Cheadle Hulme became the home of Waitrose's first purpose-built retail outlet in northern England.[61]

According to the 2001 census, the biggest industry of employment for Cheadle Hulme residents is that of wholesale and retail trade and repairs with approximately 16% of people employed in that industry. This is followed closely by real estate, renting and business activities with 15% of people employed in this area. Other big areas of employment include manufacturing (13%), health and social work (11%), and education (10%).[62][63] Approximately 30% of people were classed as "economically inactive" in the 2001 census. This included retired people, people who had to look after their family, and disabled or sick people.[64][65]

Landmarks

The Swann Lane, Hulme Hall Road, and Hill Top Avenue conservation area contains 16th and 17th century timber-framed buildings, Victorian villas, churches, and some former farmsteads.[66] There are two Grade II listed buildings in this area: Hulme Hall, a timber-framed manor house which dates from either the 16th or 17th century, and 1 Higham Street, formerly Hill Cottage, which is of a similar period and style to Hulme Hall. The Church Inn public house, which dates from either the late 18th or early 19th century, is situated on the edge of this area.[51]

Oak Meadow Park is a small park on Station Road, with a large grass area and woodland. In the early 2000s it was renovated and refurbished, with new fences, benches and footpaths. The project to maintain and improve the park is a continuous process overseen by a local volunteer group. The park is used for special community events throughout the year.[67]

Bruntwood Park has a variety of facilities, including orienteering,[68] an 18-hole, par 3 pitch and putt golf course, children's play areas, football pitches, and a BMX track.[69] Bruntwood Park is also home to The Bowmen of Bruntwood, an archery club.[70] Bruntwood Park is a Grade B Site of Biological Interest,[71] and in 1999 was given a Green Flag Award for its high standards.[72] The land it occupies was once a large estate, which at one time included a stud farm.[73] Bruntwood Hall, a Victorian Gothic building constructed in 1861, has been used for various purposes, including serving as Cheadle and Gatley Town Hall from 1944 until 1959.[74][75] It is now a hotel and since the 1940s the park has been open to the public.[73]

Around 300 men from Cheadle Hulme served in the First World War,[76] and it was decided that those who died should be commemorated. Various ideas, including a library and clock tower, were suggested and in the end a cenotaph was built on the corner of Ravenoak Road and Manor Road in 1921. It was designed by British architect Arthur Beresford Pite and created by sculptor Benjamin Clemens. Additions for later wars have been made.

Transport

Road

Although most of the roads in the area date from the 20th century, there are many older roads formed from ancient routes. Cheadle Road possibly originated in Roman times and Ack Lane (formerly Hack Lane) is named after Hacon, a local Saxon landowner.[77] Hulme Hall Road is named for the landmark it runs through and has existed since at least the 18th century.[51] Until the 20th century, the roads were little more than country lanes and most traffic consisted of horsedrawn carriages, carts and milk floats. The roads were about half as wide as they are currently and have all since been widened to accommodate the increasing amount of traffic.[50] The first cars appeared in Cheadle Hulme in the early 1900s, but horse-drawn vehicles were the main form of transport until the 1920s. A bus, known as the Rattler, was introduced around this time and ran a service through the area. It was, however, very slow and noisy, as its name suggests.[78]

The A34 Cheadle by-pass passes nearby; the A5419 and B5095 roads traverse Cheadle Hulme.[79]

Railway

The Crewe to Manchester railway was completed in May 1842 and a railway station known as Cheadle was built opposite the modern-day Hesketh Tavern. When the Stafford to Manchester railway opened in 1845, the original station closed and the present Cheadle Hulme railway station was built to accommodate the junction between the two railways.[47] The road was renamed to Station Road in the same year[19] and the station was renamed Cheadle Hulme in 1866.[80]

The station has four platforms: two that serve the Crewe to Manchester line and the other two for the Stafford to Manchester line;[81] there are three trains per hour northbound to Manchester Piccadilly, with one train per hour southbound to each of Stoke-on-Trent, Alderley Edge and Crewe.[82]

Buses

Cheadle Hulme is well served by bus routes, which are operated predominantly by Stagecoach Manchester. There are frequent services to and from Stockport and Manchester Piccadilly Gardens, as well as to places such as Bramhall, Cheadle, Grove Lane, Wythenshawe Hospital and Manchester Airport.[83]

Air

Cheadle Hulme is situated near to Manchester Airport, the busiest airport in the United Kingdom outside the London area.[84]

Education

Cheadle Hulme's first school, established in 1785, was named after local grocer Jonathan Robinson, who donated 3 acres (1.2 ha) of land on what is now Woods Lane. The school was built on what is now the corner of Woods Lane and Church Road,[85] and was originally for the teaching of four boys and four girls.[86] With the increasing population and the Education Act 1870 All Saints' National School was built across the road in 1873, next to All Saints' Church from which it took its name.[87] Other schools established in the 19th century include the Grove Lane Baptist Day School, built in 1846;[53] Cheadle Hulme School in 1855;[88] the Congregational Church School in the same year;[87] and Ramillies Hall School in 1884.[89] Hulme Hall Grammar School was established in 1928 (has since relocated),[90] Queens Road Primary School opened in 1932,[55] and the school that became Cheadle Hulme High School was built near to the site of the Jonathan Robinson School in the 1930s.[86][91] The majority of the rest of the schools in the area were established in the 1950s and 1960s, including Cheadle County Grammar School for Girls (built in 1956) which later became Margaret Danyers Sixth Form College, named after the same Danyers who was lady of the manor in the 14th century. The site is now the Cheadle campus of Cheadle and Marple Sixth Form College. In addition to the college, there are nine primary schools, two secondary schools, Cheadle Hulme High School and St. James' Catholic High School, which opened in 1980,[92] three private schools and one special school, Seashell Trust.

Culture

Venues

The East Cheshire Chess Club is located on Church Road[93] and there are two amateur theatre societies: Players' Dramatic Society on Anfield Road,[94] and Chads Theatre on Mellor Road.[95] Cheadle Hulme Library, which opened on 28 March 1936, is also located on Mellor Road.[96] Cheadle Hulme once had its own cinema named the Elysian Cinema, which was located on Station Road, but this closed in March 1974. As of 2009, the closest cinemas to Cheadle Hulme are approximately 3 miles (5 km) away in Stockport (Red Rock) and the Parrs Wood entertainment centre, both leisure complexes which include restaurants, bars, bowling and fitness facilities.[97][98][99]

Cheadle Hulme is also home to many public houses and restaurants that serve a variety of cuisine, including Indian, Chinese and Italian.[60] The John Millington, a Grade II listed building, was formerly Millington Hall, built for Stockport alderman John Millington.[100] A row of cottages near to the hall served as a meeting place for local Methodists from 1814, before a purpose-built chapel was established. A Sunday school was also established in the same place.[85] The King's Hall was built in 1937 and was originally a dance hall before its conversion into a restaurant and public house.[96]

Fitness and leisure facilities

Club Cheadle Hulme, which is attached to Cheadle Hulme High School, contains a large sports hall, a dance studio, an astro-turf pitch and gym equipment.[101] Manchester Rugby Club is located on Grove Lane in Cheadle Hulme, as is Cheadle Hulme Cricket Club, which was established in 1881,[102] and a squash club.[103] There is also a lacrosse club "Cheadle Hulme Lacrosse Club" which was established in 1893,[104] a badminton club,[105] and a sports club off Turves Road called the Ryecroft Sports Club, which has tennis courts and a bowling green.[106] The Bowmen of Bruntwood (Stockport's only archery club) is situated in Bruntwood Park. The local 11-a-side football team 'Cheadle Hulme Athletic' was established in 2009 and is currently playing in Division 2 of the Stockport District Sunday Football League.[107] 'Cheadle Hulme Galaxy FC' was established in 2013 and are currently playing in Division 2 of the Stockport District Sunday Football League.[108]

Religion

The oldest reference to Methodist meetings in the area dates to 1786[110] and regular services took place from the early 19th century when they established their own meeting places[111] with a Methodist church and Sunday school built in 1824.[112] Grove Lane Baptist Church was built in 1840.[53] Anglican worshippers used the Jonathan Robinson School from 1861 for services and in 1863 All Saints Church was built on Church Road.[113][109] Seven years later the Congregational Church opened on Swann Lane, after services were held in the school room which was built a year earlier.[114] In 1932 a second Anglican church was built: St Andrew's Church was founded as a daughter church of St Mary's Church, Cheadle.[115] During the Second World War, Roman Catholic services were held in the King's Hall on Station Road, and in 1952 St Ann's Church was opened on Vicarage Avenue.[52] Grove Lane Baptist Church was rebuilt in the late 1990s[116] and Emmanuel Church, opened in 1966 near Bruntwood Park, moved to a new building in 2001.[115]

Notable people

Actors and actresses from the area include Tim McInnerny, best known for his roles in Blackadder as Lord Percy and Captain Darling,[117] and Kirsten Cassidy, best known for playing Tanya Young in Grange Hill.[118] Other notable people from the area include blues musician John Mayall;[119] mathematician Patrick du Val;[120] violinist Jennifer Pike;[121] poet Julian Turner;[122] John Davenport Siddeley, a captain of the automobile industry;[123] James Kirk (VC);[124] Dame Felicity Peake, founder of the Women's Royal Air Force;[125] and Stuart Pilkington, a housemate in Big Brother 2008.[126]

See also

References

- ↑ "Custom report - Nomis - Official Labour Market Statistics".

- ↑ "Custom report - Nomis - Official Labour Market Statistics".

- 1 2 3 4 "Greater Manchester Gazetteer". Greater Manchester County Record Office. Places names – C. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ↑ "Cheadle Hulme North Census 2011". Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ↑ "Cheadle Hulme South Census 2011". Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- 1 2 Clarke, p. 3

- 1 2 Clarke, p. 1

- 1 2 3 4 Squire, p. 1

- ↑ Mills, A. D. (2003). Cheadle Hulme. Oxford Reference Online, Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-960908-6. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Holden, Desmond (1 July 2002). "What's in a Name?". The Peak Advertiser. GENUKI. Archived from the original on 8 August 2010. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ↑ Mills, p. 78

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lee, p. 3

- ↑ Bowden, p. 5

- ↑ Squire, p. 2

- 1 2 Arrowsmith, p. 36

- 1 2 Clarke, p. 4

- ↑ Clarke, p. 5

- ↑ Clarke, p. 7

- 1 2 3 Lee, p. 4

- ↑ "Cheshire Parishes: Cheadle Moseley". GENUKI. Retrieved 5 February 2009.

- ↑ "Cheshire Parishes: Cheadle". GENUKI. Retrieved 5 February 2009.

- ↑ Clarke, p. 19

- 1 2 Squire, p. 21

- ↑ Squire, pp. 4–5

- ↑ http://www.ijmet.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/102.pdf the info is on page 297, which is page 8 in the pdf listed in the county greater manchester

- ↑ "European Severe Weather Database". eswd.eu. Search for tornadoes occurring on 23-11-1981 and between 53°N and 54°N latitude then ctrl+f for Cheadle Hulme.

- ↑ "Genuki: Cheadle Moseley, Cheshire". genuki.org.uk.

- 1 2 Bowden, p. 25

- ↑ Bowden, p. 27

- ↑ Craig, p. 53

- ↑ Statham, Nick (8 May 2015). "Cheadle constituency results: General Election 2015 – Tories take seat from the Liberal Democrats". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ↑ "Your Councillors by Ward". Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ Arrowsmith, p. 5

- ↑ Arrowsmith, p. 7

- ↑ "Manchester Airport 1971–2000 weather averages". Met Office. 2001. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ↑ Met Office (2007). "Annual England weather averages". Met Office. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ↑ "Stockport Local Authority". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ↑ "England Country". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Cheadle Hulme Built-up area sub division". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ↑ Arrowsmith, p. 264

- ↑ Arrowsmith, p. 265

- ↑ 1981 Key Statistics for Urban Areas GB Table 1. Office for National Statistics. 1981.

- ↑ "Greater Manchester Urban Area 1991 Census". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ↑ "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area". Government of the United Kingdom. 22 July 2004. KS02 Age structure

. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

. Retrieved 16 February 2009. - 1 2 3 4 5 Lee, p. 6

- 1 2 Squire, p. 3

- 1 2 3 Lee, p. 7

- ↑ Squire, p. 5

- 1 2 Squire, p. 6

- 1 2 Squire, p. 16

- 1 2 3 "Swann Lane/Hulme Hall Road/Hill Top Avenue Conservation Area Character Appraisal". Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council. Archived from the original on 6 June 2015. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- 1 2 Squire, p. 13

- 1 2 3 Squire, p. 8

- ↑ Squire, p. 9

- 1 2 "History". Archived from the original on 27 August 2005. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ↑ Squire, p. 20

- ↑ "New police HQ is safe bet". Stockport Express. M.E.N. Media. 9 February 2005. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ↑ Scheerhout, John (11 May 2006). "Cops net £10m from old stations". Manchester Evening News. M.E.N. Media. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ↑ Garratt, p. 61

- 1 2 "Retail and Entertainment in Cheadle Hulme". Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ "IGD Retail Analysis Waitrose Store Visit reports & in-store photos". IGD Retail Analysis. Archived from the original on 14 May 2007. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ↑ "Cheadle Hulme North (Ward) Industry of Employment (UV34)". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 26 May 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ↑ "Cheadle Hulme South (Ward) Industry of Employment (UV34)". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 26 May 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ↑ "Cheadle Hulme North (Ward) Economic Activity (UV28)". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 26 May 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ↑ "Cheadle Hulme South (Ward) Economic Activity (UV28)". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 26 May 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ↑ "Swann Lane/Hulme Hall Road/Hill Top Avenue (1984, extended 2005)". Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ "Oak Meadow Focus Group". Stockport Green Space Forum. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ↑ "Bruntwood Park". Greater Manchester Orienteering Activities. 29 February 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ↑ "Facilities and Features". Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ↑ "Bowmen of Bruntwood". Stockport MBC. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ↑ "Wildlife Sites". Greater Manchester Local Records Centre. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ↑ "Select Committee on Environment, Transport and Regional Affairs". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- 1 2 "History". Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council. Archived from the original on 5 January 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

- ↑ Makepeace, p. 30

- ↑ Hudson, p. 51

- ↑ Squire, p. 14

- ↑ Lee, p. 5

- ↑ Squire, p. 17

- ↑ "Cheadle Hulme Transport Links". Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ Butt, p. 58

- ↑ "Station Facilities for Cheadle Hulme". National Rail. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ↑ "Timetables and engineering information for travel with Northern". Northern Railway. May 2023. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ↑ "Stops in Cheadle Hulme". Bus Times. 2023. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ↑ "Summary of Activity at UK Airports 2008" (PDF). UK Civil Aviation Authority. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- 1 2 Garratt, p. 14

- 1 2 Squire, p. 11

- 1 2 Squire, p. 12

- ↑ "Cheadle Hulme School: Ethos, Aims & Heritage: History". Cheadle Hulme School. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ "Ramillies Hall". Independent Schools Inspectorate. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ "Independent Schools Inspectorate Inspection Report on Hulme Hall Grammar School". Independent Schools Inspectorate. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ "Cheadle Hulme College History". Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council, via the Internet Archive. Archived from the original on 31 December 2002. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "East Cheshire Chess Club". East Cheshire Chess Club. Archived from the original on 5 September 2008. Retrieved 25 January 2009.

- ↑ "Players' Dramatic Society". Players' Dramatic Society. Retrieved 25 January 2009.

- ↑ "Find Us / Contact Us". Chads Theatre Company. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- 1 2 Squire, p. 19

- ↑ Garratt, p. 8

- ↑ "Grand Central, Stockport". Grand Central Stockport. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

- ↑ "Manchester". Parrs Wood Entertainment Centre. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

- ↑ Squire, p. 4

- ↑ "Facilities - Club Cheadle Hulme". The Laurus Trust. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ↑ "Cheadle Hulme Cricket Club". Cheadle Hulme Cricket Club. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- ↑ "Grove Park Squash Club Cheshire club located in Stockport, South Manchester". Grove Park Squash Club. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ↑ "Cheadle Hulme Lacrosse Club". Cheadle Hulme Lacrosse Club. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ↑ "Cheadle Hulme Badminton Club". Cheadle Hulme Badminton Club. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ↑ "Ryecroft Park Sports Club". Ryecroft Park Sports Club. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ↑ "Homepage – Cheadle Hulme Athletic". clubwebsite.co.uk. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ↑ "Sunday Cup 2014/15 Fixtures". Cheshire FA. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- 1 2 "History". All Saints Parish Church. Cheadle Hulme. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ↑ Makepeace, p. 106

- ↑ Garratt, p. 12

- ↑ Squire, p. 7

- ↑ Makepeace, p. 105

- ↑ Makepeace, p. 107

- 1 2 "History". St Andrew's Parish Church Council. 2009–2020. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ↑ Garratt, p. 58

- ↑ "Film guide for Cheshire and Merseyside Part of This Is Cheshire/Merseyside". This Is Cheshire. Newsquest. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ↑ haile, deborah (12 February 2003). "TV terror Tania is a class act". Manchester Evening News. M.E.N. Media. Archived from the original on 21 April 2013. Retrieved 25 January 2009.

- ↑ John Mayall’s teenage obsessions: ‘I lived in a tree house until I got married, The Guardian, 29 January 2021

- ↑ "Patrick du Val". University of St. Andrew's. Retrieved 25 January 2009.

- ↑ Downes, Robert (6 February 2008). "Cheadle Hulme girl wins top award". Community News Group. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2009.

- ↑ "Julian Turner". Inpress Books. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ Matthew, H C G; Howard Harrison, Brian (2004). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. p. 511. ISBN 978-0-19-861400-5.

- ↑ "VC Burials in France". Victoria Cross. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ↑ Condell, Diana (11 November 2002). "Air Commodore Dame Felicity Peake". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- ↑ Morley, Victoria (25 June 2008). "Big Brother hunk Stuart wins army of local fans". Stockport Express. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

Bibliography

- Arrowsmith, Peter (1997). Stockport: a History. Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council. ISBN 978-0-905164-99-1.

- Bowden, Tom (1974). Community and Change: a History of Local Government in Cheadle and Gatley. Cheadle and Gatley Urban District Council. ISBN 978-0-85972-009-0.

- Butt, R. V. J. (October 1995). The Directory of Railway Stations: details every public and private passenger station, halt, platform and stopping place, past and present (1st ed.). Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85260-508-7. OCLC 60251199. OL 11956311M.

- Clarke, Heather (1972). Cheadle Through The Ages. Manchester: E. J. Morten. ISBN 978-0-901598-44-8.

- Craig, Fred W. S. (1972). Boundaries of Parliamentary Constituencies 1885–1972. Political Reference Publications. ISBN 978-0-900178-09-2.

- Garratt, Morris (1999). Pictures and Postcards from the Past: Cheadle Hulme. Sigma Leisure. ISBN 978-1-85058-674-6.

- Hudson, John (1996). Britain in Old Photographs: Cheadle. Sutton Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7509-0641-8.

- Lee, Ben (December 1967). A History of Cheadle Hulme and its Methodism. Trustees, Cheadle Hulme Methodist Church. 40 pages.

- Makepeace, Chris E. (1988). Cheadle and Gatley in Old Picture Postcards. European Library. ISBN 978-90-288-4674-6.

- Mills, A. D. (1998). Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280074-9.

- Squire, Carol (January 1976). Cheadle Hulme: a Brief History. Recreation and Culture Division, Metropolitan Borough of Stockport. ISBN 978-0-905164-72-4.

- Wyke, Terry; Harry Cocks (2005). Public Sculpture of Greater Manchester. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-0-85323-567-5.