_-_original.jpg.webp) Original Chest in the Church of St.Simeon in Zadar | |

| Under protection of UNESCO | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| Author: | Francesco di Antonio da Sesto |

| Date: | 1377–1380 |

| Place: | Zadar, Croatia |

| Techniques: | Repoussé Silverwork and Gilding |

| Material: | Cedarwood |

| Dimensions: | 1.92×0.625×1.27 metres (6.30×2.05×4.17 ft) |

| Location: | Trg Šime Budinića, Zadar |

| Open for public viewing every year on 8 Oct. | |

The Chest of Saint Simeon or Saint Simeon's Casket (Croatian: Škrinja sv. Šimuna) is a rectangular cedarwood sarcophagus in the shape of a chasse, overlaid with silver and silver-gilt plaques, said to hold the relics of St Simon the God-receiver; it is located over the main altar in the Church of Saint Simeon in Zadar, Croatia. The chest, considered a masterpiece of medieval art and also a unique monument of the goldsmith's craft of the age, is one of the most interesting works in gold in Europe now under the protection of UNESCO.[1][2] It was made by local goldsmiths to an Italian design between 1377 and 1380.

The cult of St. Simeon, the story of how the queen stole the finger of Zadar's patron saint, or gonfaloniero as the locals call it,[2] and the donation of a magnificent shrine to atone for the stealing of the saint's finger illustrate not only the political aspect orchestrated by the Angevins amid the people's belief in the authenticity of Zadar's body over the one kept in Venice, but also the high level of development and quality in goldsmithing during the second half of the fourteenth century.

The top of the chest containing the mummified body of the silver-crowned bearded saint enclosed behind a sheet of transparent glass is elevated above the main altar and displayed to the public, as well as its interior full of precious gifts given by Elizabeth of Bosnia, every year on 8 October, at 8:30 a.m.[3][4][5][6][n 1]

History

The legend of the chest

Eastern Roman emperors who were seated in Constantinople in the sixth century were not only expanding their collection of valuable works of art, but also relics of saints in order to be able to stand side by side with Rome's. So, between 565 and 568 AD the sarcophagus where the remains of St. Simeon were being kept was moved from Syria to Constantinople,[7][n 2] where it stayed until the year 1203 when it was then shipped to Venice.[8][9][10][n 3]

According to tradition, the veneration of St. Simeon at Zadar began after the arrival of a Venetian merchant there who was transporting the relics of the saint in a stone sarcophagus when his ship was caught in a storm off Zadar, on the Dalmatian coast. While the city repaired his ship, he secretly buried the sarcophagus in a cemetery nearby so as to keep it safe from any danger; soon after that he got very ill. He sought refuge at an inn at the head of Zadar's harbour,[n 4] where monks began to treat him. Seeing that his medical condition had worsened, they took all of his documents and found an inscription hanging around his neck reporting the miraculous powers of the saint. Oddly enough, that same night, three rectors appeared to them in a dream and warned each one individually that the remains of the holy saint were really buried in that said cemetery. Early in the following morning, as they walked to the site where they expected to find that stone sarcophagus, they told one another about their vision and so realised that they all had shared the same dream. They got to the grave where the chest had been hidden and dug it out of the ground, unaware of the real powers of its content. Shortly after that, gossips about this story reported by the monks and miracles performed in the name of the saint began to spread around the region inciting to the locals to refuse to let his body leave Zadar.[3]

When the remains of St. Simeon first came to Zadar they were deposed in the cemetery of a suburban monastery (Church of the Virgin - Velika Gospa),[1] which later became associated with the city's pilgrims hospice, until they were transferred to the sacristy of the female monastery of St. Mary Major, where they remained until its demolition to make room for the construction of the city walls in 1570.[11] On 16 May 1632 they were transferred once more amid public rejoicing to a church consecrated to St. Stephen, the Martyr, and which subsequently came to be known as the Sanctuary of Saint Simeon the Righteous, the prophet of the Nunc Dimittis.[12] Since then St. Simeon, one of the four patrons of Zadar, has been revered in the city.[1]

The theft of the finger

In 1371, Elizabeth of Bosnia,[13] daughter of Stephen II, Ban of Bosnia, and Queen of Hungary and Croatia as wife of one of the most powerful European rulers of his time, King Louis I, visited the city of Zadar.[n 5] According to legend, during a religious mass, she furtively cracked off a piece of St. Simeon's finger and hid it in the breast of her dress, where it immediately began to decompose, a process which miraculously reverted itself when she returned the piece to the saint's hand. Confused by the appearing wound on her bosom and without being able to continue up to the point where she could safely exit from the church, most probably because of the maggots that infested the broken piece,[11] she ran blindly through the aisle of the church only to find out that she would soon be morally forced to restore the piece back to its original place under the accusatory and inquisitive glances exchanged by the many noblemen who formed a circle around her.

When Elizabeth finally left the church she promised to honour the saint by presenting the church with a gift ornated in gold that she later came to commission to the Milanese goldsmith Francesco di Antonio da Sesto (Francis of Milan), who was asked to create a paper model with drawings of all the details to be discussed and approved by the queen's representatives so that their legibility and presentation might be in accordance with the royal expectations and deep interest in the making of such precious shrine. The intricate carvings were dexterously executed between 1377 and 1380 and was assisted by Andrija Markov from Zagreb, Petar Blažev from Reča, Stejpan Pribičev and Mihovil Damjanov.[5][6][14][n 6][n 7]

Recent events

In 2007 the Archbishop of Zadar and the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem agreed that the Archdiocese would provide a piece of the body of the saint to the Patriarchate of Jerusalem to be venerated in the Church of the Katamon Monastery of St. Simeon. Arrangements were made with the Congregation of Divine Worship and Cult of Saints in Rome and the small silver reliquary, constraining a particle measuring 5 x 2.5 cm and bearing the Latin inscription: "Ex corporis Sancti Simeoni Iusti Zadar 7. octobris 2010", was solemnly handed over to the representatives of the Orthodox Church during the celebration of Vespers in the eastern part of the historic quarters of Zadar.[1]

Description of the chest

Dimensions

The rectangular silver chest of Saint Simeon, standing 2.3 m above the ground on the main altar of the church of the same name,[15] measures 1.92 m long by 62.5 cm wide and, including the 56 cm high saddle-shaped lid, 1.27 m high.[5] The front side of the lid is dominated by the carved reclining figure of the saint dressed in a gown and cloak richly ornamented with plant motifs made by punching fastened on his breast by a clasp. The front panel, which unfolds by means of hinges located on the bottom displaying the saint's laid-down figure, measures 66.5 cm high.[14] It is raised by the outstretched arms of four bronze angels forged from seventeenth century Turkish cannons that were seized in the waters of Zadar in 1648.[16] Covered inside and outside with a thin lamina of 240 kg of pure silver and also a considerable quantity of gold, it shows intricate details carved on the cedar wood used to give shape to the chest. All free surface of the chest is filled in with more or less standard vine, leaves and winding rosettes of sinuate leaves ornamentations decorated with gold.[14][17]

Relief compositions

The front part of the chest displays enhanced relief compositions depicting scenes from the saint's early years as a preacher, death and ascension into heaven on the back of a virgin,[15] as well as biblical and historical events of his time. The inside part contains a relief made by goldsmith Stjepan Martinič of Zadar representing the patron saints of the city in the background.[5] The inside of the lid is magnificently illustrated with three miracles attributed to the saint. His holy monk-like figure and two sets of the arms of Anjou also appear in high relief on both the triangle areas of the lid. They are both richly decorated in the same manner together with the shield of Hungarian bars and the characteristic Angevin fleur-de-lis, a cloak and a helmet with a crown. Above the crowns rises an ostrich with outspread wings and a horseshoe in its beak. Around the coat of arms there are reliefs of acanthus leaves, and beside them the initials of the king: L.R. (Latin: Lodovicus Rex).[n 8]

The Latin inscription on the central panel on the back of the chest, which corresponds to the main composition on the front panel, bears the goldsmith's signature with Louis's coat of arms in the corners of the richly worked vine tracery that complements the relief. It is divided in two parts, being the larger with the main inscription in Gothic capital letters beaten in high relief: "SYMEON: HI.C.IVSTVS.YEXVM.DE.VIRGINE.NATVM.VLNIS: QVI.TENVITHAC.ARCHA. PACE.QVIESCIT.HVNGARIE.REGINA.POTENS: ILLVSTRIS: ED.ALTA: ELYZABET.IUNIOR:QVAM.VOTO:CONTVLIT. ALMO.ANNO.MILLENO: TRECENO: OCTVAGENO." Below, angraved in stylized minuscule letters, appears the goldsmith's signature: "hoc.opus.fecit: franciscus.d.mediolano."[14]

Known in medieval Latin hexameters, the translation of the inscription reads as follows: "Simeon the Righteous, holding Jesus, born of a virgin, in his arms, rests in peace in this chest, commissioned by the Queen of Hungary, mighty, glorious and majestic Elizabeth the Younger, in the year 1380. This is the work of Francis of Milan".[1]

Main scenes

The scenes are separated by columns surmounted by small heads of angels sculpted during the two-year restoration process started in 1630.[5] The work was conducted by the goldsmiths Constantino Piazzalonga of Venice and Benedetto Libani of Zadar, who reduced the length of the chest by four and the width by three fingers.[18][19][n 9]

| Compositions located on the front side of the chest. |

|---|

|

|

|

| Compositions located on the right and left sides of the chest. |

|---|

|

|

| Compositions located on the back part of the chest. |

|---|

|

|

| Compositions located on the inside part of the front panel. |

|---|

|

|

|

| Compositions located on the back of the lid. |

|---|

|

|

Note: The visual narrative of The Theft of the Finger and two other scenes located on the back part of the chest have recently been considered to be all connected.[17] Such conclusion may differ from another line of thoughts who point to a longer narrative based on a chronological sequence of events, which begins with the scene The Boat in the Storm, shifts from visual to written discourse in the reading of the Latin inscription on the back panel, and ends in the complementary scene The Death of Ban Kotromanić.[17]

Gallery

Zadar's town walls and gates are seen here close to the Church of St. Mary the Great, in which the body of St. Simeon laid until 1570 and after which the gate was named.

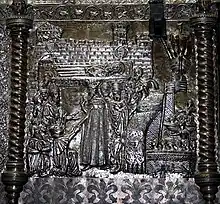

Zadar's town walls and gates are seen here close to the Church of St. Mary the Great, in which the body of St. Simeon laid until 1570 and after which the gate was named. The carving of the relief The Presentation in the Temple is expressively mentioned in the contract for the chest.

The carving of the relief The Presentation in the Temple is expressively mentioned in the contract for the chest. The gesture of the monk pointing over his shoulder is identical to that of the Virgin showing St. Francis to baby Jesus on a fresco by Pietro Lorenzetti in the Basilica of San Francesco d'Assisi.

The gesture of the monk pointing over his shoulder is identical to that of the Virgin showing St. Francis to baby Jesus on a fresco by Pietro Lorenzetti in the Basilica of San Francesco d'Assisi. According to the legend, Elizabeth went to the church accompanied by her three daughters to pay homage to the saint and also fulfill her vows as for the king's entry in Zadar in 1358.

According to the legend, Elizabeth went to the church accompanied by her three daughters to pay homage to the saint and also fulfill her vows as for the king's entry in Zadar in 1358.

See also

Notes

- ↑ The embroidering apron in which St. Simeon is dressed was a gift of the Serbian despot Djordje Brankovič.

- ↑ According to some historians, the saint's body was translated from Jerusalem to Constantinople in the second half of the 6th century while others state that it was brought to Constantinople from Syria. The mentioning of the Dubrovnik Cathedral as his first resting place in Dalmatia after his transfer from Palestine also appears in a verse-chronicle of the Ragusan poet Miletius from 1159.

- ↑ The surviving Pilgrim’s Book, written by Daniel and Anthony of Novgorod, monk and archbishop of Novgorod, during their visit to Constantinople in 1200, testifies that the relics of the saint were still in Istanbul at the time. Legends relate that his body arrived in Zadar in 1203, 1213, 1243 or 1273 respectively, but despite the many dates and places the theory that the Eastern emperor's nephew Alexius Angelus conspired with Venetians and Frankish crusaders to plounder the city of Zadar on their way to Constantinople in 1201 (Treaty of Venice) may sound quite possible to some researchers once the purpose of the plan was to defray part of the transporting cost of the expedition which the crusaders were unable to pay to Venice. In December 1202 Alexius IV promised aid and money in return for restoration to his throne, so like this the Treaty of Zara was signed in January 1203 and the Fourth Crusade proceeded against Christian Constantinople, despite protests from the Pope because the act represented a brutal assault on a Catholic town by Catholic troops. There is a mosaic in the Basilica of San Giovanni Batista in Ravenna, Italy, that portrays the invasion of Zadar by the crusaders (1208).

- ↑ This is the place where today stands the parish church of St. John.

- ↑ Jelič, however, reported that this event happened during the king's entrance in Zadar and not in 1371.

- ↑ Although Francis of Milan could have taken on assistants because of the urgency of the job, it is known today from documents that he only took on only one apprentice and one trained goldsmith who was engaged at the end of the work.

- ↑ The commission of the chest by Elizabeth is recorded in a document dated 5 July 1377 in Zadar. It reveals the techniques used in the making of the chest and also attests that the donation of the 240 kg of silver used to decorate the surface of the chest came from "Elizabeta" herself. It was most probably given to Zadar because the Royal couple needed the support of its people. Even being the commissioning of reliquary shrines a typical way by which medieval queens attempted to secure their political recognition, it was the period when the city frequently belonged to the Venetian Empire and the territory of the Croatian-Hungarian king. Thus Louis I, engaged in keeping Zadar away from the clutches of Venice, wanted a strong community to form a strong bond between the south Italian possessions and the Polish and Croatian-Hungarian state. For this reason, St. Simeon was the best choice for being the most popular saint in Zadar. But the Angevin chapter of Zadar's history, which began in 1350, ended in 1409 when Ladislaus of Naples, the descendant of Elizabeth the Cuman, sold Zadar and its duchy to the Venetian Republic.

- ↑ The same coat of arms in the shape of a buckle can be found in the treasury of Aachen Cathedral once Ludvig I was the grandson of Charles Martel, the son of Charles II of Naples.

- ↑ The art historian Rudolf Eitelberger wrote in his 1861 work Die mittelalterlieben Kunstdenkenmale Dalmatiens that the chest had been restored during the Renaissance.

- ↑ From a historical point of view, this is the most interesting piece of work as it interprets an almost contemporary event to the making of the chest. The returning of the saint's body to the place from which the Venetians had probably removed him during their ten-year-long rule, although this information is not confirmed in historical sources.

- ↑ The central relief on the front of the chest, is believed to be a work based on a fresco by Giotto, in the Scrovegni Chapel (Cappella dell'Arena) in Padua, or it might be a work based on another of Giotto's smaller paintings today in the Gardner Museum in Boston. This way Francis of Milan introduced the work of this grand master to Dalmatia.

- ↑ Writers agree that this composition depicts the finding of St. Simeon's body in a cemetery of a Zadar suburban monastery.

- ↑ This is an artistically important motif for also being reminiscent of Giovanni di Balduccio's stone relief on the sarcophagus of St. Eustorgius in Milan. Older writers have the opinion that this scene is a despiction of the boat that brought the saint's relics to Zadar and that it tells the legend of Margaret of Durazzo, wife of Duke Charles of Durazzo, Ludvig's relative, who took part of the saint's body and tried to leave Naples, but the boats which were to take them and their suite could not sail out of the harbour.

- ↑ Older writers say that this scene shows Elizabeta stealing one of St. Simeon's fingers in order to have a male heir. St. Simeon was frequently invoked for couples wishing to have a boy and the belief of stealing the finger of a saint dates at least from the time of the hagiographer Gregory of Tours. Ancient Romans consecrated every joint of the fingers of both hands to a saint and St. Simeon figures as the first joint of the middle finger of the left hand.

- ↑ As the Queen's father was a Bosnian Ban, and Bosnian rulers were often accused of the Bogumil heresy, writers say that this scene is meant to show that he was a good Catholic and that the two boys represent the Ban's nephews Tvrtko and Vuk, who came to Zadar to entreat the saint to protect their uncle. Other writers suggest that both boys personify only the eldest of the two, who was crowned King of Bosnia and Serbia in October 1377.

- ↑ Catherine (1370-1378) was seven years old, Mary (1371-1395) six and Hedwig (1373-1399) almost four at the time of the commissioning of the chest, so this relief must have been finished when Elizabeth's eldest daughter was still alive.

- ↑ These figures showing the same boy were not connected in literature and therefore were first wrongly described as two miracles instead of only one, however all three characters bear the same features, hair and attire in this composition.

- ↑ This scene has been interpreted as the preaching of the priest who attacked some religious teaching concerning the Virgin, so St. Simeon appeared in his dream with a sword and threatened him, so steering him to the right path of life.

- ↑ According with some writers, this composition shows either some false oath or a sacrilege committed by that man.

- ↑ The content of this relief has not been well explained. The figure kneeling by the post seems to represent the goldsmith working in the church who appears surprised by the arrival of the young man accompanied by the woman.

- ↑ This composition is considered by some writers to also represent the punishment of a prejurer whose sin was to become a madman for the stealing of the saint's leg, which miraculously grew together with the body again after being sent back to Zadar.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Marijan, Livio. "Part of Relics of St. Simeon the Godbearer handed over by the Archbishop of Zadar to the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem". Press Release of the Archdiocese of Zadar. Byzantine Catholic Church in America. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- 1 2 Wingfield, William Frederic (2007), A Tour in Dalmatia, Albania, and Montenegro with an Historical Sketch of the Republic of Ragusa, from the earliest times down to its final fall, p. 56. Cosimo classics travel & exploration, New York. 2007 reprint of book about 1853 tour. ISBN 1-60206-288-9

- 1 2 Višnja Arambašić, Nataly Anderson, Frank Jelinčić, Tocher Mitchell (2007). Zadar In Your Pocket, p. 22. ISBN 0-01-334922-8

- ↑ "St. Simeon". Emco Inc. Archived from the original on 12 April 2009. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Saint Simeon's Shrine". Qantara - Mediterranean Heritage. Archived from the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- 1 2 Rossiter, Stuart (1969); Yugoslavia: the Adriatic Coast, Benn, pp. 102. ISBN 0-510-02505-6

- ↑ Britannica Online. "Anthony of Novgorod". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ↑ Seymour Jr, Charles (1976). "The Tomb of Saint Simeon the Prophet in San Simeone Grande, Venice". Gesta. International Center of Medieval Art. 15 (1/2): 193–200. doi:10.2307/766767. JSTOR 766767. OCLC 4893277455. S2CID 193388734.

- ↑ Madden, Thomas F. (1993). "International History Review". Vows and Contracts in the Fourth Crusade: The Treaty of Zara and the Attack on Constantinople in 1204. Taylor & Francis. 15 (3): 441–468. JSTOR 40106727.

- ↑ O'Rourke, Michael (2011). "The Last Era of Roman Magnificence: 12th Century Byzantium and the Kommenoi Emperors". Byzantium under the Kommenoi Emperors. Scribd. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- 1 2 Bousfield Jonathan (2003). The Rough Guide to Croatia, Rough Guides, pp. 261. ISBN 1-84353-084-8

- ↑ "W Magazine" (PDF). Churches and Cultural Attractions. All Things Croatia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 August 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ↑ Fabijančić, Tony (2003). Croatia: travels in undiscovered country, The University of Alberta Press, pp. 112. ISBN 0-88864-397-7

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Petricioli, Ivo. (1996). Artistic innovations on the silver shrine of St. Simeon in Zadar, Hortus artium medievalium (vol. II), Zagreb - Motovun, pp. 9-17. OCLC 34729563

- 1 2 Santo Cilauro, Tom Gleisner, Rob Sitch (2003). Molvania: a land untouched by modern dentistry; Hardie Grant Books, pp. 58. ISBN 978-1-74066-110-2

- ↑ Raos, Ivan (1969). Adriatic tourist guide, Spektar, pp. 113. OCLC 112865 on Google Search Retrieved 15 April 2011

- 1 2 3 4 5 Munk, Ana (2004). The Queen and Her Shrine: An Art Historical Twist on Historical Evidence Concerning the Hungarian Queen Elizabeth, née Kotromanić, Donor of the Saint Simeon Shrine, International Research Center for Late Antiquity and Middle Ages and International Centres of Croatian Universities, pp. 255 ISSN 1330-7274

- 1 2 Petricioli, Ivo (1983). St. Simeon's shrine in Zadar, Drago Zdunić, pp. 26-31. OCLC 12301571

- ↑ Jackson, Sir Thomas Graham (1887). Dalmatia, the Quarnero and Istria: with Cettigne in Montenegro and the island of Grado, Clarendon, pp. 317. OCLC 1718101

- ↑ Ivančević, Radovan (1986). Art treasures of Croatia, IRO Motovun - Belgrade: Jugoslovenska revija, p. 97, OCLC 18052634

- ↑ Gyug, Richard Francis; (2002), Medieval cultures in contact, Fordham University Press, pp. 62. ISBN 0-8232-2212-8

- ↑ International Research Center for Late Antiquity and Middle Ages (2004). Hortus artium medievalium, The Center, pp. 225 (Vol. 10). OCLC 34729563

- ↑ Burdick, Lewis Dayton (2002). The hand: a survey of facts, legends, and beliefs pertaining to manual, Purdue University Press, pp. 44. ISBN 1-55753-294-X

Sources

- Radovinovič, Radovan (1998). The Croatian Adriatic, Naklada Naprijed, pp. 169–170. ISBN 953-178-097-8

- Kokole, S. (2008). The Silver Shrine of Saint Simeon in Zadar: Collecting Ancient Coins and Casts after the Antique in Fifteenth-Century Dalmatia, History of Art Studies. ISSN 0091-7338

- Bak, J.M. (1986). Roles and Functions of Queens in Arpadian and Angevin Hungary (1000-1386 A.D.), Medieval Queenship (ed) New York. ISBN 0-312-05217-0

- Attribution

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Russian Language and Literature". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- This article incorporates information translated from the corresponding article of the Croatian Wikipedia. A list of contributors can be found there at the History section.

Further reading

- Fondra, Lorenzo (1855). Istoria della insigne reliquia di San Simeone profeta che si venera in Zara, Zara : Frat. Battava, OCLC 253225165 (in Italian)

- Madden, Thomas F. (2008). The Fourth Crusade: Event, Aftermath, and Perceptions (Crusades - Subsidia) - The Translatio Symonensis and the Seven Thieves: A Venetian Fourth Crusade furta sacra Narrative and the Looting of Constantinople by David M. Perry, Society for the Study of the Crusades and the Latin East. Conference. Ashgate. ISBN 0-7546-6319-1

External links

Media related to St. Simon's casket at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to St. Simon's casket at Wikimedia Commons- Crown found in the shrine of Saint Simeon in Zara on Sigismundus website

- The Canticle of Simeon on the Catholic Encyclopedia.