| Chewaucan River | |

|---|---|

Footbridge over the Chewaucan River | |

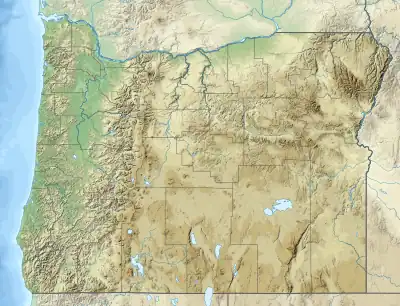

Location of the mouth of the Chewaucan River in Oregon | |

| Etymology | From the Klamath words tchua (wild potato) and keni (place)[1] |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Oregon |

| County | Lake |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Fremont National Forest |

| • coordinates | 42°27′49″N 120°36′38″W / 42.46361°N 120.61056°W[2] |

| • elevation | 5,151 ft (1,570 m)[3] |

| Mouth | |

• location | Lake Abert |

• coordinates | 42°31′21″N 120°14′59″W / 42.52250°N 120.24972°W[2] |

• elevation | 4,258 ft (1,298 m)[2] |

| Length | 53 mi (85 km)[4] |

| Basin size | 651 sq mi (1,690 km2)[5] |

The Chewaucan River is part of the Great Basin drainage. It flows 53 miles (85 km) through the Fremont–Winema National Forests, Bureau of Land Management land, and private property in southern Oregon. Its watershed consists of 651 square miles (1,690 km2) of conifer forest, marsh, and rural pasture land. The river provides a habitat for many species of wildlife, including native Great Basin redband trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss newberri), a subspecies of rainbow trout.

Course

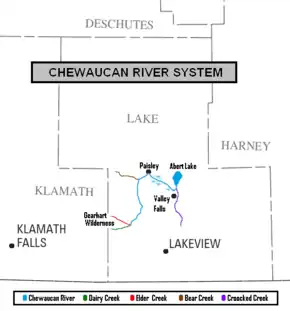

The Chewaucan flows for 53 miles (85 km) through Lake County, Oregon.[4] The sources of the Chewaucan are Elder Creek and Dairy Creek. Both have their headwaters in the east drainage of Gearhart Mountain Wilderness. The Chewaucan is the result of their merger east of the Gearhart Mountain Wilderness near Dairy Point. From there, the Chewaucan flows north through the Fremont-Winema National Forests, where waters from Ben Young Creek, Coffeepot Creek, Antelope Springs, Corral Creek, Dog Creek, Sage Hen Creek, Bear Creek, and Mill Creek flow into it before the river passes out of the forest near Paisley.[6]

The Chewaucan flows through Paisley and into what was once the Upper Chewaucan Marsh east of the town. The marsh is now pasture land, and the river's flow through this area is controlled by a system of weirs and irrigation canals. The river is consolidated for a short distance as it leaves the upper marsh at The Narrows, where two fingers of high desert uplands force the river into a single narrow channel. The river then opens into the Lower Chewaucan Marsh approximately 7 miles (11 km) northwest of Valley Falls. Finally, Crooked Creek joins the Chewaucan just one mile (1.6 km) before it empties into Abert Lake, which has no outlet.[6]

Watershed

The Chewaucan watershed drains 651 square miles (1,690 km2) of forest, marsh and rural ranch land.[5] The upper drainage, from its headwaters until it flows out of the mountains just west of Paisley, is forest country dominated with ponderosa pine, lodgepole pine, and white fir with aspen groves near springs and meadows.[7]

Below Paisley, the river flows through the 42,000-acre (17,000 ha) Chewaucan Marsh. In native condition, the marsh was probably covered with tufted hairgrass, redtop, sedges, and rushes. However, the river's flow through this area is controlled by a system of weirs and canals that provide water to irrigate the pasture lands that have replaced the marsh. The marsh is surrounded by semi-desert country with strongly alkaline soil that supports arid, alkali-tolerant plants.[8]

Habitat

In its natural state, Great Basin redband trout moved freely from the river's headwaters near Gearhart Mountain to the Chewaucan Marsh, which was covered with marsh grasses and still supports prolific insect life. Feeding in the marsh area, the native trout often grew to 30 inches (76 cm) inches in length before they returned to the Chewaucan headwaters to spawn.[9]

In the late 19th century, cattlemen turned the Chewaucan Marsh into pasture land by building a series of dams, weirs, and canals to provide irrigation. Over time, the stock of native trout dwindled. In 1925, the Oregon Game Commission (forerunner of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife) began stocking the Chewaucan with hatchery raised trout.[9]

By 1994, the Great Basin redband trout was being considered for protection under the Endangered Species Act. To help boost the redband population, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife stopped stocking the Chewaucan in 1998. This was a very unpopular decision in the Paisley community.[9]

Genetic testing revealed that native trout had not interbred with the hatchery fish. As a result, the native redband population began to increase more quickly than expected once the annual stocking was stopped. However, the dam and weir system still prevented fish from using the full length of the river. For any fish passing beyond the Paisley town weir, it was a one-way trip with little chance for survival in the irrigation canals and no chance to return upstream to spawn.[9]

In 1996, biologists discovered a small population of native Great Basin redband trout in River's End Reservoir, a private impoundment dam collecting the Chewaucan water just before it flows into Abert Lake. This discovery proved that redband trout could repopulate the entire Chewaucan watershed if they could get past the man-made obstacles into the upper river to spawn.[9]

The United States Forest Service and Oregon Fish and Wildlife biologist partnered with the Paisley community and local ranchers to make the entire Chewaucan a fish-friendly river once again. As a result of this cooperation, the Forest Service and Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board funded several projects to reopen the Chewaucan to migrating fish. In 2002, the Forest Service began replacing old culverts along the Chewaucan with new fish-friendly ones. In 2003, work began to replace the Paisley town weir, and four more watershed improvement projects were funded in 2004. While the Chewaucan Marsh cannot be returned to its natural state, since the completion of the Paisley weir project in 2006, large redband trout are once again passing downstream in the spring and returning from the marsh area into the upper river. The town of Paisley now holds an annual fishing derby to celebrate the return of the river's native redband trout population.[9][10][11]

Paisley irrigation weir

Paisley irrigation weir Restoration project

Restoration project Fish-friendly culverts

Fish-friendly culverts

In addition to the fish habitat, the Chewaucan Marsh supports a diverse population of nesting ducks and sandhill cranes. It also has nesting colonies of white-faced ibis, great egrets, and snowy egrets. The area provides excellent migration staging habitat for double-crested cormorants, snow geese, tule white-fronted geese, and black-crowned night-herons.[12]

Recreation

There are several campgrounds on the Chewaucan River. The most used site is the Chewaucan Crossing campground. The campground is located along the Chewaucan River in the Fremont– Winema National Forest approximately 8.5 miles (13.7 km) southwest of Paisley on a paved access road. It has five developed campsites with picnic tables, fire gates, and restrooms. Chewaucan Crossing is the trailhead for access to the middle section of the 115-mile (185 km) long Fremont National Recreation Trail. The elevation at Chewaucan Crossing is 4,810 feet (1,470 m) above sea level. Because of harsh winters, the Forest Service normally closes the campground in November and reopens it in April.[13]

See also

References

- ↑ McArthur, Lewis A.; Lewis L. McArthur (2003) [1928]. Oregon Geographic Names (7th ed.). Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Society Press. p. 196. ISBN 0-87595-277-1.

- 1 2 3 "Chewaucan River". Geographic Names Information System (GNIS). United States Geological Survey. November 28, 1980. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ↑ Source elevation derived from Google Earth search using GNIS source coordinates.

- 1 2 "The National Hydrography Dataset". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved September 3, 2010.

- 1 2 "Watershed Boundary Dataset". USDA, NRCS, National Cartography and Geospatial Center. Retrieved September 4, 2010. ArcExplorer GIS data viewer.

- 1 2 United States Geological Survey (USGS). "Topographic Map". TopoQuest. Retrieved October 18, 2011. The relevant quadrangles from source to mouth are Shoestring Butte, Morgan Butte, Paisley, Coglan Buttes, Tucker Hill, and Coglan Buttes SE.

- ↑ Larson, Ron (2007). "Gearhart Mountain Wilderness" (PDF). Kalmiopsis Vol. 14. National Park Service. pp. 19–20. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- ↑ Anderson, E. William; Borman, Michael M.; Krueger, William C. (1997). "The Ecological Provinces of Oregon". Oregon State University. Archived from the original on September 21, 2006. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wray, Pat (June 26, 2006). "A new chapter for the Chewaucan". The Oregonian. reprinted by Klamath Bucket Brigade. Archived from the original on October 1, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- ↑ "Chewaucan Restoration Project (Paisley Town Weir)" (PDF). U.S. Forest Service. 2003. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- ↑ "Fishing: The Chewaucan River". U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- ↑ Ivey, Gary L (September 28, 2000). "Oregon Closed Basin" (PDF). Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife and Ducks Unlimited Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 3, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- ↑ "Chewaucan Crossing Trailhead". U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved October 18, 2011.