A Chorochromatic map (from Greek χώρα chóra 'region' and χρώμα chróma 'color'), also known as an area-class, qualitative area, or mosaic map, is a type of thematic map that portray regions of categorical or nominal data using variations in color symbols. Chorochromatic maps are typically used to represent discrete fields, also known as categorical coverages. Chorochromatic maps differ from choropleth maps in that chorochromatic maps are mapped according to data-driven boundaries instead of trying to make the data fit within existing, sometimes arbitrary units such as political boundaries.[1]

History

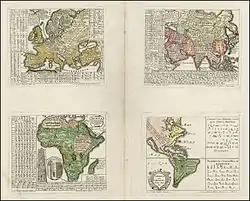

The chorochromatic map is one of the oldest types of thematic map, first appearing independently in several different fields.[2]: 52 In 1741, Gottfried Hensel published Synopsis Universae Philologiae, a book about world languages that included a set of maps of language regions, each with boundaries and colors for broad language families as he understood them. Other maps of cultural regions began to appear in the 19th Century.

The first known geologic map of surficial rock types was published by Jean-Étienne Guettard and Philippe Buache in 1746, showing matching formations crossing the English Channel in bands of gray. In the early 19th Century, these kinds of maps proliferated, especially in the United Kingdom and France, including hand-painted color.

Perhaps the first master of this technique was Heinrich Berghaus. His 1837 Physikalischer Atlas, probably the first thematic atlas ever published, includes several color chorochromatic maps. These included a variety of topics from both physical and human geography: watersheds, geology, agriculture, biogeography, and ethnicity.[3] Much of the data was apparently obtained from Alexander von Humboldt.

With the increasing availability of chromolithography in the second half of the 19th Century, chorochromatic maps proliferated to the point that the concept of filling areas with color became almost mundane. The origin of the term chorochromatic is unclear, as none of these early works mentioned it; Erwin Raisz uses the term in the 1938 textbook General Cartography.[4]

As the rise of academic cartography focused attention on the design of thematic maps to represent statistical data, maps of qualitative information received little direct research. The chorochromatic form was acknowledged as a useful technique for portraying the results of geographical analysis.[5] More research has been conducted in the era of geographic information science (starting in the 1990s) on the underlying concepts and data models of discrete fields, notably issues of vagueness that are inherent to the spatial manifestation of categories.[6][7]

Conceptual and data model

A chorochromatic map is a visualization of regions, with a nominal (qualitative) difference between them. In many cases, these regions are distinct established entities; for example, a map of land administration in the United States would include features such as national and state parks.

The second type of phenomenon that is commonly represented in chorochromatic maps, which may be the basis of more maps than the first type, is what Daniel Montello calls a thematic region.[8] This type of region is the spatial manifestation of category. That is, it is the area in which a given type of phenomenon is present; for example, the area in which a particular type of plant is predominant or where the majority of residents primarily speak a given language. Since most geographical phenomena exhibit a tendency for spatially proximate phenomena to be similar (i.e. Tobler's first law of geography), it is common to see most or all locations around one location be of the same category, whether that is climate or socioeconomic status, resulting in a relatively homogenous region.

Typically, these regions can be collected into a composite model representing the regions covered by all of the categories of a phenomenon, called a categorical coverage or discrete field.[9] Like a quantitative field, a discrete field is a property that varies over space and theoretically possesses a measurable value at any location. However, the value in this case is nominal or categorical.

Some of these classification systems are hierarchical, meaning some values are more similar to each other than others (e.g., geologic strata by age, language families). In this case, a wise choice of map symbols such as similar colors (e.g. similar shades of red) can help to portray the hierarchy effectively.[4]

The regions depicted on a chorochromatic map are very scale-dependent. It is rare that a thematic region is truly homogeneous; typically, there are smaller regions or locations that are different, but the cartographer or data manager has determined that these are not large enough to show at the scale of the map, and has merged them into the surrounding regions. For example, on a county-scale land use map, a single farm house would not be shown amid several square miles of farmland, whereas on a land use map focused on that farm, the house might be significant to show. On a land use map of an entire country, the farmland itself would probably not be large enough to show. As with all forms of Cartographic generalization, this can lead to uncertainty and misinterpretation if not done wisely.

In a Geographic information system, a discrete field may be stored in either a vector or raster format, typically chosen based on the larger context of the project. Most software has tools to symbolize either format as a chorochromatic map. For example, in Esri products such as ArcMap and ArcGIS Pro, the "Unique Values" type of symbology is available for both kinds of data. The same goes for the "Categorized" symbology type in QGIS.

Application domains

The categorized phenomena that have been mapped using chorochromatic maps are extremely varied, coming from both physical and human geography. The following are a few examples:

- Biomes

- Climate

- Land cover, such as vegetation, water, and human landscape

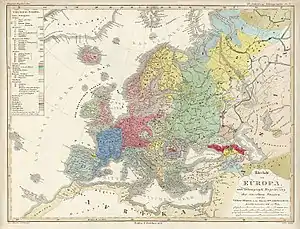

- Predominant language,[10] religion, ethnicity or other cultural trait

- Soil type

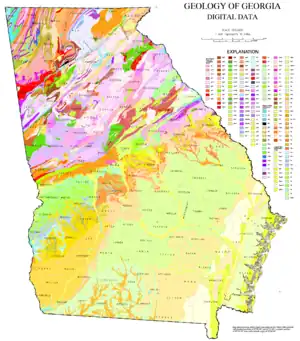

- surface geologic strata

- Land use

- city zoning

Simple and compound chorochromatic maps

Chorochromatic maps can be categorized as either simple or compound.[11]

Simple chorochromatic

Simple chorochromatic maps show single regions or categories with spatially intermittent frequencies (i.e., there are gaps between the regions). An example of this would be showing the distribution of forests or mineral deposits. The chosen variable is represented by a single color symbol or pattern without subdividing it further into subgroups.

Compound chorochromatic

Compound chorochromatic maps represent a full discrete field, consisting of a set of regions of different categories. One example would be a full vegetation map, in which the different kinds of vegetation are all shown on the same map, using different symbols or shading patterns.

Relationship to choropleth maps

Because most types of thematic maps are designed to portray quantitative data, one could assume that a nominal variable would dictate the creation of a chorochromatic map.[12] However, choropleth maps can be used to portray nominal data that is created by aggregating and summarizing a geographic variable within predetermined districts. The critical difference between each, then, lies in the nature of the geographical unit used in each.

As an example, a Primary Language variable in census data could be aggregated into the predominant spoken language in each county in a country, then visualized in a choropleth map. Conversely, in a chorochromatic map, the regions would be drawn based on detailed geographic data. Thus, a chorochromatic map of predominant language would have irregular boundaries based on where the language regions are located in reality.

Criticisms

Chorochromatic maps, like other thematic maps, have the potential to be misinterpreted by their readers. For example, the map reader may assume that the size of a given area is proportional to the number of people in the area with a qualitative characteristic such as language or religious belief. To avoid misleading a map user, a cartographer may choose to add a diagram showing the actual numbers involved and additional explanations in the legend or map layout to help to create a clear understanding of the map.[13]

Another challenge for chorochromatic maps is that they may suggest defined boundaries between regions where none may exist. Because most categorical coverages are the spatial manifestations of categories, vagueness in the definition of those categories will be manifest as vagueness in the regions (especially around their boundaries).[7] Thus some variables when mapped, such as language, can suggest to the viewer a rigidity to the borders between features that may or may not exist in reality.[6][14] When areas of uncertainty are present, cartographers may need to employ other techniques to suggest a degree of uncertainty or vagueness between each feature.[15]

References

- ↑ Kraak, Menno-Jan; Ormeling, Ferjan (2003). Cartography: Visualization of Geospatial Data (2nd ed.). Harlow, England: Prentice Hall. p. 129. ISBN 978-0130888907.

- ↑ Robinson, Arthur H. (1982). Early Thematic Mapping in the History of Cartography. University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Bergmann, Heinrich (1837). Physikalischer Atlas oder Sammlung von Karten (1st ed.). Justus Perthes Gotha. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- 1 2 Raisz, Erwin, General Cartography, 2nd Edition, McGraw-Hill, 1948, p.245

- ↑ Monkhouse, F.J.; Wilkinson, H.R. (1971). Maps and Diagrams: Their Compilation and Construction (3rd ed.). Harper & Row. pp. 38, 267, 331, 403.

- 1 2 Burrough, Peter; Frank, Andrew U. (1996). Geographic Objects with Indeterminate Boundaries. Taylor & Francis.

- 1 2 Plewe, Brandon (1997). "A Representation-Oriented Taxonomy of Gradation". Spatial Information Theory: A Theoretical Basis for GIS. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer-Verlag. 1329: 121–136.

- ↑ Montello, Daniel R. (2003). "Regions in Geography: Process and Content". In Duckham, Matthew; Goodchild, Michael F.; Worboys, Michael F. (eds.). Foundations of geographic information science. Taylor & Francis. pp. 173–189.

- ↑ Chrisman, Nicholas R. (1997). Exploring Geographic Information Systems. Wiley.

- ↑ Carlevaro, Tazio (1992). "Geolinguistics. Journal of the American Society of Geolinguistics". Language Problems and Language Planning. 16 (2): 194–196. doi:10.1075/lplp.16.2.10car. ISSN 0272-2690.

- ↑ Adejuwon, O. (1975). "A Note on the Comparison of Chorochromatic Surfaces". Geographical Analysis. 7 (4): 435–440. doi:10.1111/j.1538-4632.1975.tb01056.x. ISSN 0016-7363.

- ↑ Thomas, Isabelle (March 6, 2001). "Thematic cartography today: recalls and perspectives". Cybergeo: European Journal of Geography. 189: 6. S2CID 14647533.

- ↑ Kraak, Menno-Jan; Oremling, Ferjan (2010). Cartography: Visualization of Spatial Data (3rd ed.). New York City: Rutledge. p. 140. ISBN 978-1609181932.

- ↑ Luebbering, Candice R.; Kolivras, Korine N.; Prisley, Stephen P. (2013-11-01). "The lay of the language: surveying the cartographic characteristics of language maps". Cartography and Geographic Information Science. 40 (5): 383–400. doi:10.1080/15230406.2013.809892. ISSN 1523-0406.

- ↑ Plewe, Brandon (1997) The Cartographic Representation of Gradation, Proceedings, ACSM/ASPRS 1997, Seattle, WA.