| Chromodoris orientalis | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| Subclass: | Heterobranchia |

| Order: | Nudibranchia |

| Suborder: | Doridina |

| Superfamily: | Doridoidea |

| Family: | Chromodorididae |

| Genus: | Chromodoris |

| Species: | C. orientalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Chromodoris orientalis Rudman, 1983 | |

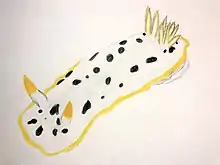

Chromodoris orientalis is a species of colourful sea slug, a dorid nudibranch, a marine gastropod mollusc in the family Chromodorididae.[1][2] Sea slugs are generally very beautifully colored organisms with intense patterns and ranging in sizes. The Chromodoris orientalis specifically is a white sea slug with black spots in no particular pattern with a yellow, orange, or brown in color ring around its whole body and on its gills. There is much discussion on where it is found, what it eats, how it defends itself without a shell, and its reproduction methods. This is all sought after information because there is not much known about these animals.

Distribution

This species has been reported from Japan, Hong Kong and Korea.[3]

Japan

It is commonly found in the Sagami Bay and on the Echizen Coast of Japan.[4]

Taiwan

The Chromodoris orientalis are more common in Japan, but have been seen in Taiwan and recorded in March and April 1983, by Bernard Picton.[5]

Hong Kong

The Chromodoris orientalis was spotted and recorded in Hong Kong in October 2000, by Leslie Chan.[6]

Description

Chromodoris orientalis is translucent white with oval black spots on the mantle. The edge of the mantle has a narrow orange border and the rhinophore clubs and outer gill surfaces are orange.[3] The rhinophores are scent and taste receptors that protrude on the front of the sea slug, the gills protrude on the opposite end from the rhinophores. They, like other sea slugs, also have a foot which is their main source of locomotion, they use this muscular foot to crawl around on different surfaces in the ocean. Their mantle is thick and covers their foot and is used as a protection, as it secretes its toxins for chemical defense. It is unsure the exact size and weight these animals can grow to be.

Diet

Chromodoris orientalis have various feeding methods and are generally carnivorous. They feed on sponges, hydroids, bryozoans, entoprocts, and ascidians.[7] They use their lack of shell to be able to change size and shape in order to fit into a higher multitude of places to prey on their food.[8]

Defense

Sea slugs are very different than terrestrial slugs, but one similarity they do have is their lack of shell. it is thought that they both have a lack of shell due to their evolution of other, maybe more effective, defense mechanisms.[9] It is thought that they also lack their shells because it enables them to better camouflage themselves, it allows them to change shape easier and fit into a multitude of more hiding places, or places that they can prey on their food.[8] Nudibranch have a very well executed chemical defense that they use which is stored and then excreted by the mantle when they are feeling attacked or in distress.[10]

Reproduction

Chromodoris orientalis lay eggs in "egg ribbons" that are attached along one edge. These "egg ribbons" are generally on algae, but not impossible to be laid on rocks or other surfaces. There have been minimal studies on these eggs being laid other places besides algae.[11] They reproduce sexually. Egg size was studied among them and three others in the Chromodoris genus, and it was found that eggs size varied among species but did not change within species depending on the parental body length. The number of egg whorls also varied depending on the species.[12] They are simultaneous hermaphrodites (as are all animals in the order Nudibranchia), meaning they possess both male and female reproductive organ at the same time. Because they are simultaneous hermaphrodites, when they mate they dart their penises at one another and the first to penetrate becomes the dominant male. Their life cycle consists of eggs laid in whorls, they then hatch to become vestigial veliger larvae until they grow into adults.[13]

References

- ↑ Caballer, M. (2015). Chromodoris orientalis Rudman, 1983. In: MolluscaBase (2015). Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species on 2015-12-06

- ↑ Bouchet P. & Rocroi J.-P. (Ed.); Frýda J., Hausdorf B., Ponder W., Valdes A. & Warén A. 2005. Classification and nomenclator of gastropod families. Malacologia: International Journal of Malacology, 47(1-2). ConchBooks: Hackenheim, Germany. ISBN 3-925919-72-4. ISSN 0076-2997. 397 pp.

- 1 2 Rudman, W.B., 2001 (July 5) Chromodoris orientalis Rudman, 1983. [In] Sea Slug Forum. Australian Museum, Sydney.

- ↑ Masayoshi, Nishina (August 29, 2001). "Chromodoris orientalis from Japan". seaslugforum.net.

- ↑ Serene, P. R. (1952-06-16). "Etude d'une collection de stomatopodes de l'Australian Museum de Sydney [Study of a collection of stomatopods from the Australian Museum, Sydney]". Records of the Australian Museum. 23 (1): 1–24. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.23.1952.617. ISSN 0067-1975.

- ↑ Chan, Tin-yau. Hong Kong biodiversity museum (Thesis). The University of Hong Kong Libraries. doi:10.5353/th_b3198194.

- ↑ Nakano, Rie; Hirose, Euichi (May 26, 2011). "The Veiliger". Field Experiments on the Feeding of the Nudibranch Gymnodoris SPP. (Nudibranchia: Doridina: Gymodorididae) in Japan. Department of Chemistry, Biology, and Marine Science, Faculty of Science, University of the Ryukyus, Nishihara, Okinawa 903-0213, Japan. 51 (2): 66–75.

- 1 2 Faulkner, DJ; Ghiselin, MT (1983). "Chemical defense and evolutionary ecology of dorid nudibranchs and some other opisthobranch gastropods". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 13: 295–301. Bibcode:1983MEPS...13..295F. doi:10.3354/meps013295. ISSN 0171-8630.

- ↑ Wägele H, Klussmann-Kolb A (February 2005). "Opisthobranchia (Mollusca, Gastropoda) - more than just slimy slugs. Shell reduction and its implications on defence and foraging". Frontiers in Zoology. 2 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-2-3. PMC 554092. PMID 15715915.

- ↑ Avila, C; Paul, VJ (1997). "Chemical ecology of the nudibranch Glossodoris pallida:is the location of diet-derived metabolites important for defense?". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 150: 171–180. Bibcode:1997MEPS..150..171A. doi:10.3354/meps150171. hdl:10261/150343. ISSN 0171-8630.

- ↑ Allan, Joyce K. (1932-04-20). "A new genus and species of sea-slug, and two new species of sea-hares from Australia". Records of the Australian Museum. 18 (6): 314–320. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.18.1932.736. ISSN 0067-1975.

- ↑ Trickey, Jennifer S.; Vanner, Jennifer; Wilson, Nerida G. (November 2013). "Reproductive variance in planar spawningChromodorisspecies (Mollusca: Nudibranchia)". Molluscan Research. 33 (4): 265–271. doi:10.1080/13235818.2013.801394. ISSN 1323-5818.

- ↑ Miller, M. C.; Willan, R. C. (July 1986). "A review of the New Zealand arminacean nudibranchs (Opisthobranchia: Arminacea)". New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 13 (3): 377–408. doi:10.1080/03014223.1986.10422671. ISSN 0301-4223.