| Church of San Bernardino da Siena | |

|---|---|

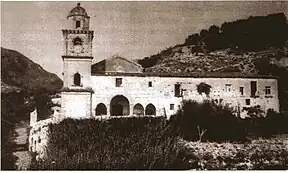

The facade and the bell tower | |

Church of San Bernardino da Siena | |

| 39°08′05″N 16°04′43″E / 39.13471°N 16.07869°E | |

| Location | Amantea, Calabria, Italy |

| Address | Via San Bernardino |

| Denomination | Catholic |

| History | |

| Founded | 1436 |

| Dedication | Bernardino of Siena |

| Consecrated | 1436 |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Gothic |

| Groundbreaking | 15th century |

| Completed | 15th century |

| Administration | |

| Archdiocese | Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Cosenza-Bisignano |

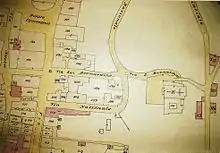

The Church of San Bernardino da Siena is a Catholic place of worship in the Italian municipality of Amantea, in the province of Cosenza in Calabria. It is situated 34 metres (112 ft) above sea level on the street of the same name in the Tyrrhenian town.

The church, dating back to the first half of the 15th century and declared a national monument, is flanked by another smaller place of worship once home to the archconfraternity of the Immaculate Conception, the Oratory of the Nobles, and the convent of the Friars Minor, founded in 1436 and occupied again by the friars since 1995, after their last departure from the building in 1861.[note 1]

History

The foundation: 15th and 16th centuries

The foundation of the Amantean convent of Observant Friars Minor in the Rota district[1] was authorized by Pope Eugene IV with the Papal brief given in Bologna on September 24, 1436:[2] the pope probably took an interest in the matter, which was of a merely local character, due to the intervention of his private steward, the Amantean nobleman Giovanni Cozza.[3] The minor observants had already settled in other localities in Calabria, where the order had been brought by Blessed Tommaso Bellacci from Florence:[2] in Tropea and Cosenza in 1421, in Mesoraca in 1428, in Reggio Calabria in 1431, and in Cinquefrondi in 1436.[4]

In all these cases, observant minors had occupied places of worship abandoned by other religious orders: this was probably also the case in Amantea. In fact, the Papal Brief signed by Eugene IV mentions, as noted by the scholar Francesco Samà,[5] a "licentia acceptandi" ("permission to accept") the convent, that is, a convent probably already existed and did not need to be built, since the University and the citizens of Amantea had offered those abandoned locations to the Observants. In addition, the old church bell, currently preserved in the cloister of the convent, bears an inscription that dates the first casting of it to 1404.[4] Finally, scholar Alessandro Tedesco has identified in a notarial deed concerning the making of the marble diptych for the oratory of the Nobles, dated 1491, evidence that about sixty years after the settlement of the Observants in the convent and the consequent dedication of the church to St. Bernardine of Siena, the population continued to call the church by its ancient name of "monasterium Sancti Francisci de Amantea."[6] From all this, it is inferred that the first occupants of the convent had been some minor conventual friars who had abandoned the Franciscan monastery located in the Catocastro district at the foot of Amantea's castle near the church of St. Francis of Assisi, now in ruins.[4][7][8]

In the 15th century the convent was visited by some distinguished individuals:[9][10] Saint Francis of Paola, the Observant Minor from Cosenza Father Antonio Scozzetta, who died in Amantea in the odour of sanctity, the vicar general of the Observant Minors Pietro of Naples and the Duke of Calabria Alfonso II of Naples all stayed there.

In 1581, the archconfraternity of the Immaculate Conception was founded,[11] a confraternity reserved only for the city's nobles:[12] the lower classes and sailors, on the other hand, gathered in the confraternity of the Most Holy Rosary.[12] The archconfraternity of the Immaculate Conception chose the church of San Bernardino as its headquarters, and beginning in 1592, it began construction of the Oratory of the Nobles.[13] This oratory was built on the site of the chapel of jus patronatus of the Cavallo family, which had recently become related to another noble Amantean family, the Baldacchini, through the marriage of Giacomo Cavallo and Prudenza Baldacchini:[13] it was these spouses who commissioned, in 1608, their own tomb to be placed in the oratory from the Messina sculptor Pietro Barbalonga.[13] Barbalonga was recalled to the Oratory of the Nobles in 1619, when the first rector of the archconfraternity, the Amantean nobleman Fabrizio Mirabelli, commissioned him to design the family tomb.[14]

17th and 18th centuries: earthquakes and restoration works

The 1638 earthquake severely damaged the church, resulting in the collapse of the bell tower,[14] which was later rebuilt several times and damaged by other earthquakes. After the plague of 1656, the Archconfraternity of the Immaculate Conception undertook new work in the oratory of the Nobles, and the minor observants began to sell space for individual burials or family pits under the floor of the church, for the obvious purpose of "making cash" for the maintenance of the convent.[14] Other figures who were buried in the church included the governor of Amantea Giacinto Santucci († 1664), castellans Antonio Spiriti († 1769), Pasquale Gabriele († 1787), Giuseppe Poerio († 1801), soldier Casimiro Belluomo († 1785), physician Ignazio de Fazio and his heirs and successors (upon payment of an annual fee of 10 carlins as established in 1672), priest Giovanni Battista Posa (upon payment of 8 ducats as established in 1676), the noble Amantean bishop of Termoli Antonio Mirabelli († 1688).[15]

The 1783 earthquake severely damaged the church by collapsing the bell tower, rebuilt after the previous earthquake in 1638, and part of the entrance porch.[16]

During the 1806-1807 siege of Amantea by the French army commanded by Generals Guillaume Philibert Duhesme, Jean Reynier and Jean Antoine Verdier, the besiegers encamped near San Bernardino,[16] located outside the city walls, bombarding from this square the castle of Amantea, which capitulated only on February 7, 1807, after two months of siege.[17]

The convent, sacked by French soldiers and emptied of its friars, was officially closed on August 7, 1809, after the approval of the laws subverting ecclesiastical property in the Kingdom of Naples.[16] Ownership of the property passed to the state property, which leased the church and the convent to the Amantean nobleman Giulio Sacchi on September 5, 1812, upon payment of the annual rent of 42.97 ducats (but the estimated value of the complex amounted to nearly 5,000 ducats).[18] Sacchi eventually turned the convent into his own palace, although soon, after the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte, the Congress of Vienna, the shooting of Joachim Murat at Pizzo Calabro on October 13, 1815, and the return of Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies to Naples, the Friars Minor Observant returned to possession of the convent, but only to cede ownership of the building and church to the diocese of Tropea, which called the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer, commonly called the "Redemptorists", to occupy it: they occupied the convent on February 11, 1833.[19]

Abandonment and restoration: from the 1800s to the 2000s

The "Redemptorists" were not well accepted by the population of Amantea, in part because they were not in a condition to permanently inhabit the convent, and also because the building was by then in the process of collapsing: in 1843 a dispute began between the religious and the Decurionate of Amantea regarding a torrential watercourse that, due to the administration's failure to comply, had encroached on the lands of the religious. Thus, as early as 1842 the Archconfraternity of the Immaculate Conception expressed the desire to purchase the convent in order to assign it once again as the residence of the Observant Friars Minor, a desire put into action only in 1847:[20] after all, the "Redemptorists" themselves already agreed in 1845 that it was better to reopen the convent of the Observant Friars Minor,[20] given their inability to garrison the convent and the damage that the Amantean Christian community was receiving.

By 1851–1852 some much-needed restoration work had been carried out by the archconfraternity on the church, at a total cost of 1,366 ducats,[21] and in 1854 some of the convent premises were rented to private families, while much of the building remained under restoration. In the 19th century an auditorium was also built above the left aisle,[21] for use as a meeting hall and concert venue. Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies authorized the reopening of the convent of the Friars Minor Observant on August 10, 1855,[22] and on November 7 of that same year the notarial deed was signed providing that the archconfraternity of the Immaculate Conception would pay 25 ducats for the rent of the convent and church to the "Redemptorists" and that the Observants would pay the same amount to the archconfraternity.[22]

The convent was permanently closed after the Unification of Italy as a result of the royal decree-law subverting ecclesiastical property issued on February 12, 1861.[22] Even though in 1862 the prefect of Cosenza had authorized the friars to return to San Bernardino, they did not accept the invitation,[9] probably due to a shortage of individuals, as had also happened in other convents in the province. The building returned to state property, and was damaged by the 1905 earthquake, which had its epicenter near Mount Poro in what is now the province of Vibo Valentia and during which the highest instrumental magnitude value ever recorded in Italy was registered:[23] at San Bernardino, the damage was limited to the collapse of the top of the bell tower and the roof of the first span of the church.[21]

The current appearance of the church is largely due to the interventions directed by Gilberto Martelli in 1953, which provided for the restoration of the ancient and essential Gothic architecture at the expense of the Baroque marble altars placed in the side chapels, and on the outside the rearrangement of the entrance porch.[21]

These interventions were consolidated and renewed by the last restorations undergone by the church in the early 1990s, with the repaving of the entire complex in square terracotta tiles and the construction of the electrical and lighting systems.[21] In fact, in 1995 the Observant Friars Minor returned to Amantea, after more than a century of absence.[22]

While the church, dependent on the parish of the collegiate church of San Biagio, was always officiated, despite the poor condition of the bell tower[24] and the copious water infiltration in the south wall,[25] the convent was used for different purposes: first the seat of some municipal offices, the municipal archives and a secondary school, then a mental health center and later the headquarters of the local health authority,[26] only after the aforementioned work in the early 1990s was it restored and used for its original purpose.

Description

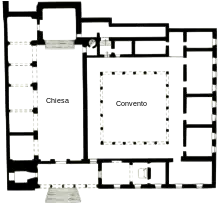

The church

The entrance porch

The entrance porch of the church is framed between the bell tower and the northwest corner of the convent, the one that houses the oratory of the Nobles: it is raised two metres (6.6 ft) above the ground, and is accessed via a staircase that tends to narrow upward. Interventions in 1953 restored the porch to its original 15th-century appearance, with the five ogival arches supported by twin polygonal pillars with drop capitals[27] mounted on high plinths, all in local sandstone:[28] after the 1783 earthquake, in fact, the central archway, the one giving access to the porch, had been converted to a round arch in the form of a serlian, with the benefit of making the church's entrance portal visible but the downside of upsetting the architecture of the porch.[16] Originally, the porch was open on two sides, but after the 1638 earthquake, the relocation of the bell tower forced the closure of the two ogival arches located to the north:[14] interventions in the 1990s revealed the remains of these arches in the base of the south wall of the bell tower.[29]

Set off from the arches of the porch is the travertine entrance portal to the church, which has a wide, low-slung arch, perhaps of Catalan inspiration,[27][28] "outlined by slender bundled curbs interspersed with smooth areas."[28] Other portals facing the porch are that of the bell tower, a round arch of modest architecture,[28] that of the convent, another lowered arch of modest architecture made partially with restoration elements,[28] and that of the Oratory of the Nobles: this sandstone portal, on the other hand, is a significant example of late Renaissance architecture.[28] It is in fact presented with an architrave framed by pilasters of the Ionic order decorated with an ovolo motif, supporting a high entablature:[29] the date of the portal's construction, legible on the ruined inscription in the center of the entablature, is 1592.[29]

The facade

The essential lines of the church's gabled façade rise behind the entrance porch: in the center a small monofora opens in a pointed arch, surmounted by the recesses in which, until 1984, ten ceramic basins were individually arranged in the shape of a Latin cross.[29] The practice of asymmetrically inserting colored ceramic or marble pieces into masonry in order to "break" the monotony of the plain-colored wall is attested in many medieval buildings,[30] such as the 15th-century Palazzo Ghisilardi Fava in Bologna or the Romanesque bell tower of the church of San Pietro in Albano Laziale: that of San Bernardino in Amantea is, however, the only 15th-century example of this practice found in southern Italy.[31] Amantean ceramics can be attributed to the Spanish ceramics factory in Manises,[31] near Valencia, which in the 15th century was the main center for the production and export of Hispano-Moorish ceramics.[32] The ceramic basins, which survived earthquakes and bad weather, were removed by the Archaeological Superintendence of Calabria on April 5, 1984,[33] transported to the National Archaeological Museum of Reggio Calabria and returned to the city of Amantea only in 2005: today they are kept in the convent of the Observant Friars Minor.[29] Prior to the placement of the plates, a large cross had been painted on the plaster, traces of which were still visible in the 1930s when Alfonso Frangipane went up to view the ceramic basins.[34] To date, copies of the ceramic basins have been constructed and then placed in early January 2018.

The bell tower

The appearance of the 15th-century bell tower, which was completely destroyed in the 1638 earthquake, is unknown. In the subsequent reconstruction, the bell tower was moved to the northern side of the entrance porch.[14] After the 1783 earthquake, a small dome was added to the top, and the three levels were distinguished by the addition of projecting cornices.[16] The small dome, which partially collapsed in the 1905 earthquake,[21] was replaced by a terraced roof. The top of the bell tower deteriorated rapidly, and by the late 1970s much of the third level had disappeared,[24] including the clock inserted in the third level's arched window and visible in some photographs from the 1930s. The bell tower took on its present appearance, with the incomplete reconstruction of the third level, with work in the 1990s.

The old bronze bell is preserved today in the cloister of the convent: a readable inscription on it reports that it was first cast in 1404, thus before the arrival of the Friars Minor Observant and the construction of the church as we know it, then it was recast in 1500 and then in 1861.[4]

The interior

The central nave

The central nave, which measures about thirty metres (98 ft) in length and ten metres (33 ft) in width and is the larger of the two naves that make up the church, is not divided into bays, is covered by an exposed wooden truss roof,[35] and is separated from the left nave by five ogival arches resting on sandstone square-section pillars.[35]

The nave is illuminated by four monoforas on each side, but the last monofora toward the counterfacade on both walls is shorter: currently the monoforas on the left side are blind after the 19th-century construction of the auditorium located above the left nave.[35]

Along the walls of the nave and on the counterfacade, blind arches, both ogival and round arches, and traces of pillars that are not compatible with the current conformation of the church, and therefore referable to the structure of the church prior to the arrival of the Observant Friars Minor in 1436, were brought to light during interventions in the 1990s.[36] Other anomalies in the structure are represented by the niche on the left wall of the nave between the arches of the first and second bays,[36] in which the marble statue of St. Francis of Assisi from a 16th-century Sicilian workshop is currently placed,[37] and by the singular section of the pillar placed between the fourth and fifth bays in relation to the other pillars.[36]

On the back wall of the nave near the triumphal arch of access to the presbytery are the bust, inscription and family crest of the noble Amantean bishop of Termoli Antonio Mirabelli.[38]

The left nave

The left nave is divided into six bays, the first of which is anomalous, since it is divided from the left nave by a wall: which led scholar Alessandro Tedesco to speculate that it might have been a 16th-century chapel of the archconfraternity of the Immaculate Conception.[36] In general, there is a certain unevenness between the various bays: beyond the thickness of the pillars, which is irregular between the first and second bays and between the third and fourth, the last three bays have a rib-vaulted roof with sandstone ogives, while the first three have no ogives.[36] This would suggest that the nave is the result of the union of several private chapels of jus patronatus, a hypothesis supported by the presence of the coats of arms of the Amantean noble families of Carratelli and Di Lauro in the fifth and sixth bays, respectively,[36] and by a walled inscription in the first bay referring to the Amantean nobleman Tiberio Cavallo placed next to a mascaron commonly identified with the Sol Invictus.[36]

From the sixth bay through a trapdoor there is access to the only sepulchral room still accessible in the church, the one formerly reserved for the Observant Friars Minor.[38] Above the cross vaults of the left nave, an auditorium was built in the 19th century, which was covered with a wooden truss roof similar to the original during the 1953 interventions.[26] In the first bay is placed a Carrara marble "Madonna and Child" by Antonello Gagini, dated 1505 and commissioned by Nicola d'Archomano, a citizen of Amantea:[7] this work, due to the richness and plasticity of the drapery and the particular effect of some unfinished parts achieves "a remarkable expressive outcome," according to scholar Enzo Fera.[7] Gagini also sculpted other statues of the same subject in Mesoraca, Morano Calabro and Nicotera, before leaving for Rome where he worked with Michelangelo Buonarroti on the tomb of Pope Julius II at the San Pietro in Vincoli basilica.[7]

Before the 1953 interventions, the left nave was enriched by numerous marble side altars, of which the one in the second bay and that of St. Lucy of Syracuse, made of local Lapis Lacedaemonius, stood out in the 1930s.[37]

The chancel

The chancel, oriented eastward as in the early Christian and mendicant tradition,[39] is set six steps higher than the modern floor of the church, and is opened by a large sandstone ogival triumphal arch:[38] it is of quadrangular plan covered by a cross vault with ogives resting on crochet or hook capitals typical of Gothic architecture,[38] and is not particularly bright, perhaps in part due to the blinding of one of the three monoforas that illuminated it, due to the 19th-century construction of the auditorium.[38]

Access from the chancel to the choir is made on the northern wall through a simple round arch, while on the southern wall, in addition to the access to the sacristy, there is an example of a credenza for storing the cruets of water and wine and the pyxes of hosts to be consecrated.[7] during the celebration of the Eucharist.[38] The splayed rectangular window on the back wall of the chancel is occupied by a stained-glass window placed there in the 1990s depicting the christogram IHS (symbol of St. Bernardine of Siena), with a twelve-rayed sun standing for the twelve apostles.[40]

The Oratory of the Nobles

The Oratory of the Nobles is located in the northwest corner of the convent: it consists of a single nave, and is covered by a flat ceiling with wooden beams. Lighting comes to it from two large windows located on the right wall.[41] The small place of worship was built in 1592, judging from the poorly legible inscription on the sumptuous entrance portal described above,[28] as a meeting place for the archconfraternity of the Immaculate Conception, intended for the nobles of the city. The room of the oratory is divided by a kind of triumphal arch that delimits the presbyterial area from the area intended for the faithful: on this arch in 2003 an image of the Immaculate Conception and the coat of arms of the archconfraternity were painted in two ovoid tablets.

The altar of the oratory is the work of the Messina sculptor Pietro Barbalonga, to whom is owed the creation of the pilasters of Ionic order and the small marble statue of the Madonna and Child placed above the lintel: the latter, however, would also be attributable to an anonymous Calabrian artist of the 14th century.[42] In the center of the altar is placed the "Nativity of Our Lord," a marble altarpiece attributed by Alessandro Tedesco to Pietro Bernini and by Alfonso Frangipane and Enzo Fera to Rinaldo Bonanno:[43] it is a 16th-century work. On either side of the altar, in two niches, was placed the marble diptych of the Annunciation by Francesco di Cristofano da Milano, commissioned in 1491 by the friars.[44]

Near the altar a small fragment of the ancient floor of the oratory and of the entire San Bernardino complex, made of black and white sea pebbles, is still preserved.[45] Also under the altar through a trapdoor there is access to the crypt of the oratory, which extends under the same for its entire length.[45] Along the nave are affixed the coats of arms of the Amantean noble families who were historically members of the archconfraternity: in 2000 the families represented in the archconfraternity were those of the Amato, the Carratelli, the Cavallo, the Cavallo Marcello, the Cavallo Marincola, the Di Lauro, the Mileti, and the Mirabelli Centurione.[45]

The convent

The cloister of the convent has a quadrangular plan, bordered on three sides by ogival arches supported by sandstone square-section pillars, and on the fourth towards the church by round arches on circular-section pillars in the Aragonese style.[40] The scholar Alessandro Tedesco notes how the archivolts placed at the corners of the cloister are enriched by capitals with plant motifs "of unquestionable classical inspiration."[40]

The convent was completely renovated in the 1990s, on the occasion of the return of the Observant Friars Minor in 1995:[21] during the course of the work, numerous archaeological remains came to light, which were made visible through a glass panel covering on the floor of the ground floor.[40] In fact, masonry and a dense network of canalizations probably belonging to the ancient convent that existed before that of the Conventual Friars Minor came to light.[40]

See also

Notes

- ↑ San Bernardino has also been described as "the most significant example of the architectural poetics spread by the mendicant orders in the 15th century in Calabria" (Tedesco, p. 31), and as the "civic temple" of Amantea (Fera, p. 39), a point of reference for the entire town community, not only for Christians.

References

- ↑ Segreti (1994, p. 12)

- 1 2 Tedesco (2008, p. 17)

- ↑ Turchi (2002, p. 41)

- 1 2 3 4 Tedesco (2008, p. 18)

- ↑ Francesco Samà, San Bernardino di Amantea: un colosso dell'architettura monastica francescana, "Calabria Letteraria", anno XLIV nn. 1-2-3, gennaio-febbraio-marzo 1996, p. 62.

- ↑ Tedesco (2008, p. 19)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fera (2000, p. 45)

- ↑ Vincenzo Segreti, La chiesa monumentale di San Bernardino da Siena di Amantea, "Calabria Letteraria", anno XXIV nn. 10-11-12, ottobre-novembre-dicembre 1976, p. 21.

- 1 2 Fera (2000, p. 49)

- ↑ Tedesco (2008, p. 20)

- ↑ Turchi (2002, p. 77)

- 1 2 Segreti (1994, p. 13)

- 1 2 3 Tedesco (2008, p. 21)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tedesco (2008, p. 22)

- ↑ Tedesco (2008, p. 23)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tedesco (2008, p. 24)

- ↑ Turchi (2002, p. 126)

- ↑ Tedesco (2008, p. 25)

- ↑ Tedesco (2008, p. 26)

- 1 2 Tedesco (2008, p. 27)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tedesco (2008, pp. 29–30)

- 1 2 3 4 Tedesco (2008, p. 28)

- ↑ "P. Galli e D. Molin, Il terremoto del 1905 in Calabria: revisione del quadro macrosismico ed ipotesi sismogenetiche, GNGTS 2007" (PDF). Retrieved August 25, 2009.

- 1 2 Tedesco (2008, p. 38)

- ↑ Tedesco (2008, p. 40)

- 1 2 Tedesco (2008, p. 31)

- 1 2 Fera (2000, p. 42)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tedesco (2008, p. 44)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tedesco (2008, p. 45)

- ↑ Gaetano Ballardini, La maiolica italiana dalle origini al Cinquecento, p. 33.

- 1 2 Maria Pia di Dario Guida, La cultura artistica in Calabria. Dall'alto Medioevo all'età aragonese, p. 261.

- ↑ Tedesco (2008, p. 67)

- ↑ Tedesco (2008, p. 68)

- ↑ Fera (2000, p. 44)

- 1 2 3 Tedesco (2008, p. 47)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tedesco (2008, p. 48)

- 1 2 Fera (2000, p. 48)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tedesco (2008, p. 50)

- ↑ Fera (2000, p. 41)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tedesco (2008, p. 51)

- ↑ Tedesco (2008, p. 56)

- ↑ Tedesco (2008, p. 61)

- ↑ Fera (2000, p. 51)

- ↑ Fera (2000, p. 47)

- 1 2 3 Tedesco (2008, pp. 57–58)

Bibliography

- Frangipane, Alfonso (April 1939). I bacini di Amantea, "Bruttium".

- Matelli, Gilberto (1954). Chiese monastiche calabresi del secolo XV: la chiesa di San Bernardino ad Amantea, "Palladio".

- Segreti, Vincenzo (1976). La chiesa monumentale di San Bernardino da Siena di Amantea, "Calabria Letteraria".

- Russo, Francesco (1982). I Francescani Minori Conventuali in Calabria, 1217-1982. Catanzaro: Silipo & Lucia Editori.

- Segreti, Vincenzo (1994). I Cappuccini di Amantea - La confraternita dell'Addolorata. Soveria Mannelli: Calabria Letteraria Editrice.

- Samà, Francesco (1996). San Bernardino di Amantea: un colosso dell'architettura monastica francescana, "Calabria Letteraria".

- Antonello Savaglio; Elisabetta Mazzei (2007). San Bernardino d'Amantea. a cura dell'Ordine Frati Minori Conventuali di Calabria ; Arciconfraternita Maria SS. Immacolata di Amantea.

- Savaglio, Antonello (2000). Committenza nobiliare in San Bernardino di Amantea: l'opera dello scultore messinese Pietro Barbalonga (1608-1619), "Calabria Letteraria".

- Fera, Enzo (2000). Amantea: la terra, gli uomini, i saperi. Cosenza: Luigi Pellegrini Editore. ISBN 88-8101-078-X.

- Turchi, Gabriele (2002). Storia di Amantea. Cosenza: Edizioni Periferia. ISBN 88-87080-65-8.

- Tedesco, Alessandro (2008). Testimonianze dell'architettura francescana nel territorio amanteano. Soveria Mannelli: Calabria Letteraria Editrice. ISBN 978-88-7574-171-6.