| Ciliary body | |

|---|---|

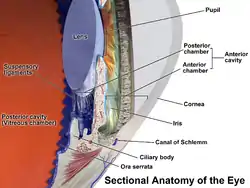

Anterior part of the human eye, with ciliary body near bottom. | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Eye |

| System | Visual system |

| Artery | long and short posterior ciliary arteries |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | corpus ciliare |

| MeSH | D002924 |

| TA98 | A15.2.03.009 |

| TA2 | 6765 |

| FMA | 58295 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The ciliary body is a part of the eye that includes the ciliary muscle, which controls the shape of the lens, and the ciliary epithelium, which produces the aqueous humor. The aqueous humor is produced in the non-pigmented portion of the ciliary body.[1] The ciliary body is part of the uvea, the layer of tissue that delivers oxygen and nutrients to the eye tissues. The ciliary body joins the ora serrata of the choroid to the root of the iris.[2]

Structure

The ciliary body is a ring-shaped thickening of tissue inside the eye that divides the posterior chamber from the vitreous body. It contains the ciliary muscle, vessels, and fibrous connective tissue. Folds on the inner ciliary epithelium are called ciliary processes, and these secrete aqueous humor into the posterior chamber. The aqueous humor then flows through the pupil into the anterior chamber.[3]

The ciliary body is attached to the lens by connective tissue called the zonular fibers (fibers of Zinn). Relaxation of the ciliary muscle puts tension on these fibers and changes the shape of the lens in order to focus light on the retina.

The inner layer is transparent and covers the vitreous body, and is continuous from the neural tissue of the retina. The outer layer is highly pigmented, continuous with the retinal pigment epithelium, and constitutes the cells of the dilator muscle. This double membrane is often considered continuous with the retina and a rudiment of the embryological correspondent to the retina. The inner layer is unpigmented until it reaches the iris, where it takes on pigment. The retina ends at the ora serrata.

The space between the ciliary body and the base of the iris is the ciliary sulcus.[4]

Nerve supply

The parasympathetic innervation of the ciliary body is the most clearly understood. Presynaptic parasympathetic signals that originate in the Edinger-Westphal nucleus are carried by cranial nerve III (the oculomotor nerve) and travel through the ciliary ganglion. Postsynaptic fibers from the ciliary ganglion form the short ciliary nerves. Parasympathetic activation of the M3 muscarinic receptors causes ciliary muscle contraction, the effect of contraction is to decrease the diameter of the ring of ciliary muscle.[5] The parasympathetic tone is dominant when a higher degree of accommodation of the lens is required, such as reading a book.[6]

The ciliary body is also known to receive sympathetic innervation via long ciliary nerves.[7] When test subjects are startled, their eyes automatically adjust for distance vision.[8]

Function

The ciliary body has three functions: accommodation, aqueous humor production and resorption, and maintenance of the lens zonules for the purpose of anchoring the lens in place.

Accommodation

Accommodation essentially means that when the ciliary muscle contracts, the lens becomes more convex, generally improving the focus for closer objects. When it relaxes, it flattens the lens, generally improving the focus for farther objects.

Aqueous humor

The ciliary epithelium of the ciliary processes produces aqueous humor, which is responsible for providing oxygen, nutrients, and metabolic waste removal to the lens and the cornea, which do not have their own blood supply. Eighty percent of aqueous humor production is carried out through active secretion mechanisms (the Na+K+ATPase enzyme creating an osmotic gradient for the passage of water into the posterior chamber) and twenty percent is produced through the ultrafiltration of plasma. Intraocular pressure affects the rate of ultrafiltration, but not secretion.[9]

Lens zonules

The zonular fibers collectively make up the suspensory ligament of the lens. These provide strong attachments between the ciliary muscle and the capsule of the lens.

Clinical significance

Glaucoma is a group of ocular disorders characterized by high intraocular pressure-associated neuropathies.[10] Intraocular pressure depends on the levels of production and resorption of aqueous humor. Because the ciliary body produces aqueous humor, it is the main target of many medications against glaucoma. Its inhibition leads to the lowering of aqueous humor production and causes a subsequent drop in the intraocular pressure. There 3 main types of medication affecting the ciliary body:[11][12]

- Beta blockers, the second most common treatment method for glaucoma, reduce the production of aqueous humor. They are relatively inexpensive and are available in generic form. Timolol, Levobunolol, and Betaxolol are common beta blockers prescribed to treat glaucoma.

- Alpha-adrenergic agonists work by decreasing production of fluid and increasing drainage. Brimonidine and Apraclonidine are two commonly prescribes alpha agonists for glaucoma treatment. Alphagan P uses a purite preservative, which is better tolerated by those who have allergic reactions than the older BAK preservative in other eye drops.[13] Furthermore, less selective alpha agonists such as epinephrine may decrease the production of aqueous humor through vasoconstriction of the ciliary body (only for open-angle glaucoma).

- Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors also decrease fluid production. They are available as eye drops (Trusopt and Azopt) and pills (Diamox and Neptazane). This may be helpful if using more than one type of eye medication.

See also

References

- ↑ Standring, Susan; Gray, Henry (2008). Gray's anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice. [Edinburgh]: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-443-06684-9. OCLC 213447727.

- ↑ Cassin, B. and Solomon, S. Dictionary of Eye Terminology. Gainesville, Florida: Triad Publishing Company, 1990.

- ↑ Lang, G. Ophthalmology: A Pocket Textbook Atlas, 2 ed.. Pg. 207. Ulm, Germany. 2007.

- ↑ Schnaudigel OE. Anatomie des Sulcus ciliaris [Anatomy of the ciliary sulcus]. Fortschr Ophthalmol. 1990;87(4):388-9. German. PMID: 2210569.

- ↑ Moore KL, Dalley AF (2006). "Head (chapter 7)". Clinically Oriented Anatomy (5th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 972. ISBN 0-7817-3639-0.

- ↑ Hibbs, Ryan E.; Zambon, Alexander C. (2011). "Agents Acting at the Neuromuscular Junction and Autonomic Ganglia". In Brunton, Laurence L.; Chabner, Bruce A.; Knollmann, Björn C. (eds.). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2015-05-22.

- ↑ Ruskell, G. L. (1973). "Sympathetic innervation of the ciliary muscle in monkeys". Experimental Eye Research. 16 (3): 183–90. doi:10.1016/0014-4835(73)90212-1. PMID 4198985.

- ↑ Fleming, David G.; Hall, James L. (1959). "Autonomic Innervation of the Ciliary Body: A Modified Theory of Accommodation". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 48 (3): 287–93. doi:10.1016/0002-9394(59)90269-7. PMID 13823443.

- ↑ Murgatroyd, H.; Bembridge, J. (2008). "Intraocular pressure". Continuing Education in Anaesthesia, Critical Care & Pain. 8 (3): 100–3. doi:10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkn015.

- ↑ Casson, Robert J; Chidlow, Glyn; Wood, John PM; Crowston, Jonathan G; Goldberg, Ivan (2012). "Definition of glaucoma: Clinical and experimental concepts". Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology. 40 (4): 341–9. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.2012.02773.x. hdl:2440/73277. PMID 22356435.

- ↑ "Glaucoma Medications and Their Side Effects". Glaucoma Research Foundation.

- ↑ "Medication Guide". Glaucoma Research Foundation.

- ↑ Colo., Malik Y. Kahook, MD, Aurora. "The Pros and Cons of Preservatives". Retrieved 2017-03-13.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Histology image: 08011loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- Atlas image: eye_1 at the University of Michigan Health System - "Sagittal Section Through the Eyeball"