A modern cimbasso in F | |

| Brass instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 423.233.2 (Valved aerophone sounded by lip vibration with cylindrical bore longer than 2 metres) |

| Developed | early 19th century, in Italian opera orchestras; modern design emerged mid 20th century |

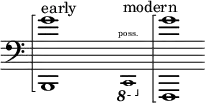

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

| Musicians | |

| |

| Builders | |

| |

The cimbasso is a low brass instrument that covers the same range as a tuba or contrabass trombone. First appearing in Italy in the early 19th century as an upright serpent, the term cimbasso came to denote several instruments that could play the lowest brass part in 19th century Italian opera orchestras. The modern cimbasso design, first appearing as the trombone basso Verdi in the 1880s, has four to six rotary valves (or occasionally piston valves), a forward-facing bell, and a predominantly cylindrical bore. These features lend its sound to the bass of the trombone family rather than the tuba, and its valves allow for more agility than a contrabass trombone. Like the modern contrabass trombone, it is most often pitched in F, although models are occasionally made in E♭ and low C or B♭.

In the modern orchestra, cimbasso parts are usually played by tuba players as a doubling instrument. Although most commonly used for performances of late Romantic Italian opera, it has since found increased and more diverse use. Jazz musician Mattis Cederberg uses cimbasso in big bands and as a solo instrument. Cimbasso is now commonly called for in film and video game soundtracks. Los Angeles tuba players Tommy Johnson, Doug Tornquist and Jim Self have featured on many Hollywood recordings playing cimbasso, particularly since the popularisation of loud, low-brass heavy orchestral soundtracks.

Etymology

The Italian word cimbasso, first appearing in the early 19th century, is thought to be a contraction used by musicians of the term corno basso or corno di basso (lit. 'bass horn'), sometimes appearing in scores as c. basso or c. in basso.[3] The term was used loosely to refer to the lowest bass instrument available in the brass family, which changed over the course of the 19th century. In the mid-20th century the word cimbasso began to be used in German-speaking countries to refer to slide contrabass trombones in F.[4] This vagueness long impeded research into the instrument's history.[5]

History

The first uses of a cimbasso in Italian opera scores from the early 19th century referred to a narrow-bore upright serpent similar to the basson russe (lit. 'Russian bassoon'), which were in common use in military bands of the time.[6] These instruments were constructed from wooden sections like a bassoon, with a trombone-like brass bell, sometimes in the shape of a buccin-style dragon's head.[7] Fingering charts published in 1830 indicate these early cimbassi were most likely to have been pitched in C.[8]

Later, the term cimbasso was extended to a range of instruments, including the ophicleide and early valved instruments, such as the Pelittone and other early forms of the more conical bass tuba. As this progressed, the term cimbasso was used to refer to a more blending voice than the "basso tuba" or "bombardone", and began to imply the lowest trombone.[9]

By 1872, Verdi expressed his displeasure about "that devilish bombardone" (referring to an early valved tuba) as the bass of the trombone section for his La Scala première of Aida, preferring a "trombone basso".[10] By the time of his opera Otello in 1887, Milan instrument maker Pelitti had produced the trombone basso Verdi (sometimes trombone contrabbasso Verdi, or simply trombone Verdi), a contrabass trombone in low 18′ B♭ wrapped in a compact form and configured with 4 rotary valves. Verdi and Puccini both wrote for this instrument in their later operas, although confusingly, they often referred to it as the trombone basso, to distinguish it from the tenor trombones.[11] This instrument blended with the usual Italian trombone section of the time—three tenor valve trombones in B♭—and was the prototype for the modern cimbasso.[9]

By the early 20th century the tuba was used in Italy for cimbasso parts, and the trombone Verdi, made mainly by Milanese and Bohemian manufacturers, disappeared from Italian orchestras. In 1959 German instrument maker Hans Kunitz developed a slide contrabass trombone in F with two valves based on a 1929 patent by Berlin trombonist Ernst Dehmel.[12] These were built in the 1960s by Gebr. Alexander and named "cimbasso" trombones.[4] The modern cimbasso found today emerged in Germany in the 1970s, its design ultimately descended from the Pelitti trombone Verdi design. Bremen brass instrument maker Thein took the contrabass trombone in F, fitted it with the valves and fingering of a modern F tuba, and named this new instrument the "cimbasso".[13]

Construction

The modern cimbasso is usually built with four to six rotary valves (or occasionally piston valves), a forward-facing bell, and a predominantly cylindrical bore. These features lend its sound to the bass of the trombone family rather than the tuba, and its valves allow for more agility than a contrabass trombone.[14] Like the modern contrabass trombone, it is most often pitched in 12′ F, although instruments are made in 13′ E♭ and occasionally low 16′ C or 18′ B♭.[2]

The mouthpiece and leadpipe are positioned in front of the player, and the mouthpiece receiver is sized to fit tuba mouthpieces. The valve tubing section is arranged vertically between the player's knees and rests on the floor with a cello-style endpin, and the bell is arranged over the player's left shoulder to point horizontally forward, similar to a trombone.[15][16] This design accommodates the instrument in cramped orchestra pits and allows a direct, concentrated sound to be projected towards the conductor and audience.

The bore tends to range between that of a contrabass trombone and a small F tuba, 0.587 to 0.730 inches (14.9–18.5 mm), and even larger for the larger instruments in low C or B♭.[17] The bell diameter is usually between 10 and 11.5 inches (250 and 290 mm).[2] There has been demand over time for larger bore instruments with a more conical bore and larger bell, in contrast with the trombone-like sound from smaller cylindrical bore instruments. This is because cimbasso parts are often played in the modern orchestra by tuba players, particularly in the US. Czech manufacturer Červený caters to both needs in its 2021 catalog which lists two cimbassi in F, one model with a small 0.598-inch (15.2 mm) bore and 10-inch (250 mm) bell listed with their valve trombones, and another with a tuba-like bore of 0.717 inches (18.2 mm) and a larger 11-inch (280 mm) bell with much wider flare, listed with their tubas.[18]

The cimbasso is usually built with rotary valves, although some Italian makers use piston valves. British instrument maker Mike Johnson builds cimbassi with four compensating piston valves as commonly found on British tubas, in both F/C and E♭/B♭ sizes.[19] Los Angeles tubist Jim Self had a compact F cimbasso built in the shape of a euphonium, which has been named the "Jimbasso".[20] In 2004 Swiss brass instrument manufacturer Haag released a cimbasso in F built with five Hagmann valves and a 0.630-inch (16.0 mm) bore. Although discontinued, this instrument is used by several operas and orchestras, including Badische Staatskapelle, Hungarian State Opera, and Sydney Symphony Orchestra, and by Swedish jazz musician Mattis Cederberg.[21]

Repertoire and performance

Although the cimbasso in its modern form is most commonly used for performances of late Romantic Italian operas by Verdi and Puccini, since the mid 20th century it has found increased and more diverse use. Along with the contrabass trombone, it has increasingly been called for in film and video game soundtracks. Los Angeles tuba players Tommy Johnson, Doug Tornquist and Jim Self have appeared on many Hollywood soundtracks playing cimbasso,[22][20] especially since the popularization of loud, low-brass heavy orchestral music in films and video games such as the remake of Planet of the Apes (2001), Call of Duty (2003) and Inception (2010).[23] British composer Brian Ferneyhough calls for cimbasso in his large 2006 orchestral work Plötzlichkeit, and nu metal rock band Korn used two cimbassos in the live backing orchestra for their acoustic MTV Unplugged album.[24] Swedish jazz trombonist Mattis Cederberg has been using cimbasso in jazz, both as a solo instrument and for playing the fourth trombone parts in big bands.[25]

Historically informed performance of early cimbasso parts presents particular challenges. Unless proficient with period instruments such as serpent or ophicleide, it is difficult for orchestral low-brass players to perform on instruments that resemble the early cimbassi in form or timbre. It is also challenging for instrument builders to find good surviving examples to replicate or adapt.[26]

Although there is still a lack of consensus from conductors and orchestras, using a large-bore modern orchestral C tuba to play cimbasso parts is considered inappropriate by some writers and players. Italian organologist Renato Meucci recommends using only a small narrow-bore F tuba, or a bass trombone.[27] James Gourlay, conductor and former tubist with BBC Symphony Orchestra and Zürich Opera, recommends playing most cimbasso repertoire on the modern F cimbasso, as a compromise between the larger B♭ trombone contrabbasso Verdi instrument and the bass trombone. He also recommends using a euphonium in the absence of a period instrument for early cimbasso parts, which is closer to the sound of the serpent or ophicleide that would have been used before 1860.[28] Douglas Yeo, former bass trombonist with Boston Symphony Orchestra, even suggests that in a modern section of slide trombonists playing parts intended for valved instruments, it should not be unreasonable to perform the cimbasso part on a modern (slide) contrabass trombone.[29]

References

- ↑ Meucci 1996, p. 155–6.

- 1 2 3

- Brass Instruments (PDF). Kraslice, Czech Republic: V.F. Červený & Synové. 2021. pp. 17–18. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- "Cimbasso" (in Italian). Milan: G&P Wind Instruments. Archived from the original on 1 March 2023. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- "Cimbasso". Weinfelden: Haag Brass. Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- "Cimbasso" (in German). Markneukirchen: Helmut Voigt. Archived from the original on 1 March 2023. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- "Contrabass Cimbasso". Markneukirchen: Jürgen Voigt. Archived from the original on 1 March 2023. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- "CB-900 Cimbasso in F". Bremen, Germany: Lätzsch Custom Brass. Archived from the original on 19 October 2022. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- "Cimbasso". Melton Meinl Weston. Buffet Crampon. 17 May 2016. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- "MJC Cimbassi". Mike Johnson Custom Instruments. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- "Cimbasso". Rudolf Meinl Metalblasinstrumente (in German). Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- "Cimbasso". Bremen: Thein Brass. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- "Cimbassos". Wessex Tubas. Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ↑ Meucci 1996, p. 144–5.

- 1 2 "Posaune; III. Sondermodelle". Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart: allgemeine Enzyklopädie der Musik (in German). Vol. 7 (2nd ed.). Kassel, New York: Bärenreiter. 1994. p. 877. ISBN 978-3-761-81139-9. LCCN 95116833. OCLC 882180506. Wikidata Q112109526. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ↑ Meucci 1996, p. 157, note 69.

- ↑ Bevan 2000, p. 81.

- ↑ "Instruments: basson russe". Berlioz Historical Brass. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ↑ Myers 1986, pp. 134–136.

- 1 2 Meucci 1996, p. 158–9.

- ↑ Bevan 2000, p. 406–13.

- ↑ Bevan 2000, p. 414.

- ↑ Yeo 2021, pp. 36–37, "contrabass trombone".

- ↑ Gourlay 2001, p. 7.

- ↑ Meucci, Renato (2001). "Cimbasso". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.05789. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ↑ Yeo 2021, p. 152, "trombone basso Verdi".

- ↑ Meucci 1996, p. 158, Fig. 13 (p. 179).

- ↑ Rudolf Meinl Prospekt (PDF). Diespeck, Bavaria: Rudolf Meinl Musikinstrumenten-Herstellung. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ↑ Brass Instruments (PDF). Kraslice, Czech Republic: V.F. Červený & Synové. 2021. pp. 17–18. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ↑ "MJC Cimbassi". Mike Johnson Custom Instruments. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- 1 2 "Jim Self's Instruments". Basset Hound Music. 2017. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ↑ "Haag Cimbasso Trombone C45HV". Haag Trombones. Musik Haag AG. Archived from the original on 12 March 2013.

- ↑ Kifer 2020, p. 85–86.

- ↑ Kifer 2020, p. 48.

- ↑ Korn (2007). "MTV Unplugged". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ↑ WDR Big Band (6 April 2023). Dave Brubeck – Unsquare Dance (music video). Brubeck, Dave (composer); Pfeifer-Galilea, Stefan (arranger); Mintzer, Bob (director); Cederberg, Mattis (cimbasso). Cologne: Westdeutscher Rundfunk. Archived from the original on 22 May 2023. Retrieved 22 May 2023 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Meucci 1996, p. 162.

- ↑ Meucci 1996, p. 161–2.

- ↑ Gourlay 2001, p. 8–9.

- ↑ Yeo 2017, p. 246.

Bibliography

- Bevan, Clifford (2000). The Tuba Family (2nd ed.). Winchester: Piccolo Press. ISBN 1-872203-30-2. OCLC 993463927. OL 19533420M. Wikidata Q111040769.

- Gourlay, James (2001), The Cimbasso: Perspectives on Low Brass performance practise in Verdi's music (PDF), Wikidata Q118373994, archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2007

- Kifer, Shelby Alan (2020), The Contrabass Trombone: Into the Twenty-First Century (DMA thesis), doi:10.17077/ETD.005304, Wikidata Q118378306

- Meucci, Renato (1996). Translated by William Waterhouse. "The Cimbasso and Related Instruments in 19th-Century Italy". The Galpin Society Journal (published March 1996). 49: 143–179. ISSN 0072-0127. JSTOR 842397. Wikidata Q111077162.

- Myers, Arnold (1986). "Fingering Charts for the Cimbasso and Other Instruments". The Galpin Society Journal (published September 1986). 39: 134–136. doi:10.2307/842143. ISSN 0072-0127. JSTOR 842143. Wikidata Q118373974.

- Yeo, Douglas (2017). The One Hundred Essential Works for the Symphonic Bass Trombonist. Maple City: Encore Music Publishers. ISBN 978-1-5323-3145-9. Wikidata Q111957781.

- Yeo, Douglas (2021). An Illustrated Dictionary for the Modern Trombone, Tuba, and Euphonium Player. Dictionaries for the Modern Musician. Illustrator: Lennie Peterson. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-538-15966-8. LCCN 2021020757. OCLC 1249799159. OL 34132790M. Wikidata Q111040546.

External links

Media related to Cimbasso at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cimbasso at Wikimedia Commons- Recordings of orchestral excerpts by Jack Adler-McKean, including an early cimbasso and a B♭ Verdi cimbasso by Orsi built c. 1902–1918, as well as serpent, ophicleide and other early tubas

- Excerpts of Verdi's Nabbucco arranged for four cimbassi (three in F by Červený, one custom-built in low B♭), performed by German tubist Daniel Ridder

- Mattis Cederberg's "Cimbassonista" YouTube playlist

_MET_DP249508_mod1.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)