| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Unknown (present) 10,000 (mid-19th century) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Northern Dobruja (formerly) | |

| Languages | |

| Circassian, others | |

| Religion | |

| Mainly Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Circassians |

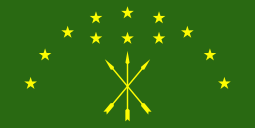

The Circassians in Romania (Circassian: Урымыныем ис Адыгэхэр, Wurımınıyem yis Adıgəxər; Romanian: cerchezi or circazieni) were an ethnic minority in the territory that constitutes modern Romania. The presence of people with names derived from the Circassians in lands belonging now to Romania was attested since at least the 15th century. For the next few centuries, these records of such people in the Romanian principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia would continue.

In 1864, as a result of the Circassian genocide, a total of 10,000 Circassians would settle in Northern Dobruja, where they would remain for about 14 years until their expulsion as agreed in the Treaty of San Stefano, which gave this region to Romania. This Dobrujan Circassian community influenced the area, having indirectly funded the construction of buildings still standing today in Tulcea and having two Romanian villages in Northern Dobruja, Cerchezu and Slava Cercheză, named after them.

Today, there are some people in both Romania and the closely related Moldova with the surname Cerchez or similar, which are clearly derived from the Circassians. In 1989, there were about 99 Circassians in Moldova, although the existence of a Circassian minority in Romania had most likely already ended by the time the 20th century had started due to assimilation.

History

In Moldavia and Wallachia

Documents from the times of the Principality of Moldavia show that names derived from the Circassians were attested as early as in the 15th century. It is in this time when, in 1435, Cerchiaz, a cantor of the royal council of Moldavia, was recorded. In 1661, the existence of a boyar (noble) named Cherchiaz Gheorghe was also recorded. People like this were also attested in the Principality of Wallachia; documents from the 17th century record Cercheza Maria, wife of a treasurer named Aslan. It is uncertain whether Cercheza was a proper name in itself or if it only referred to the ethnic origin of the person.[1]

The concept of the Circassian beauty, widely known in Western Europe in the past and according to which Circassian women were of great beauty, also arrived to Romania, with the Romanian poet Dimitrie Bolintineanu embodying it in his poem Esmé.[2]

It is believed that, by the start of the 20th century, the Circassian minority in Romania had already disappeared as a result of assimilation.[2]

In Dobruja

Following the Circassian genocide committed in 1864 by the Russian Empire, many Circassians had or were forced to abandon their homeland. Around 200,000 Circassians settled in the Balkans, 10,000 of which did in Northern Dobruja (specially in the Babadag district), then part of the Ottoman Empire. There, they would become one of the Muslim peoples of the region together with the local Tatars and Turks. In Dobruja, the Circassians were granted privileges by the Ottoman authorities and would frequently enter in conflict with the Christian population of the region, specially with the more wealthy German settlers, but also with the Muslims of Dobruja. They would raid villages of the various populations of the region and then give parts of their gains to the Ottoman authorities, which would instead do nothing to stop their attacks. It is believed the Palace of the Pasha (now the Tulcea Art Museum) and the Azizyie Mosque of Tulcea were built with funds coming from Circassian raiders.[3][4]

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 would be a key moment in the history of the Dobrujan Circassians. They saw the Bulgarians as guilty for the war, as they had revolted against the Ottoman Empire earlier in the April Uprising of 1876. Thus, during the conflict, many Circassian fighters massacred Bulgarians and also Lipovans (ethnic Russians of Dobruja) and Ukrainians, especially in Tulcea. Because they were perceived as highly problematic, in the Treaty of San Stefano that put an end to the war, a clause was added whereby the Circassians of the newly liberated Balkan lands, including Dobruja, would be expelled.[3][4] It is believed that the few that remained assimilated into the local population, notably into the Tatar one.[2] Additionally, through this treaty, Romania gained control of Northern Dobruja. This way, the Dobrujan Circassians (which only stayed 14 years in the region) and the Romanian authorities never had any particular interaction. Today, two villages in Romania, Cerchezu and Slava Cercheză, both in Dobruja, are named after the Circassians.[3][4]

Legacy

Nowadays, in both Romania and Moldova exists the surname Cerchez or variations of it. These surnames are derived from the Turkish word for the Circassians, çerkez. In Moldova, as of 2013, 877 people had the surname Cerchez.[1] In fact, in the 1989 Soviet census, 99 people declared Circassian ethnicity (40 declared themselves as Adyghe, 43 as Kabardians and 16 as Cherkess, all of them being Circassian subgroups) in the Moldavian SSR (as Moldova was then part of the Soviet Union).[5]

See also

References

- 1 2 Cosniceanu, Maria (2013). "Nume de familie provenite de la etnonime (I)". Philologia (in Romanian). 266 (1–2): 75–81.

- 1 2 3 Istrate, Ana Mihaela. "Femeia de origine cercheză în literatura și pictura romantică din spațiul Principatelor Române" (PDF). Romanian Economic and Business Review. Romanian-American University: 201–206.

- 1 2 3 Tița, Diana (16 September 2018). "Povestea dramatică a cerchezilor din Dobrogea". Historia (in Romanian).

- 1 2 3 Parlog, Nicu (2 December 2012). "Cerchezii: misterioasa națiune pe ale cărei pământuri se desfășoară Olimpiada de la Soci". Descoperă.ro (in Romanian).

- ↑ "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР – Молдавская ССР". Demoscope Weekly (in Russian). Archived from the original on 25 January 2016.