A national personification is an anthropomorphic personification of a state or the people(s) it inhabits. It may appear in political cartoons and propaganda.

Some personifications in the Western world often took the Latin name of the ancient Roman province. Examples of this type include Britannia, Germania, Hibernia, Hispania, Helvetia and Polonia.

Examples of personifications of the Goddess of Liberty include Marianne, the Statue of Liberty (Liberty Enlightening the World), and many examples of United States coinage. Another ancient model was Roma, a female deity who personified the city of Rome and his dominion over the territories of the Roman Empire.[1]

Examples of representations of the everyman or citizenry in addition to the nation itself are Deutscher Michel, John Bull and Uncle Sam.[2]

Gallery

.jpg.webp) Iudaea Capta, "Conquered Judaea", commemorative coin issued by the Roman emperor Vespasian (left) after the Jewish War

Iudaea Capta, "Conquered Judaea", commemorative coin issued by the Roman emperor Vespasian (left) after the Jewish War

Italia und Germania (1828) by Johann Friedrich Overbeck.

Italia und Germania (1828) by Johann Friedrich Overbeck. In this Allegory depicting the 1576 Pacification of Ghent by Adriaen Pietersz van de Venne, the seated women represent a short-lived unity among the embattled provinces of what would become the present-day Belgium and Netherlands

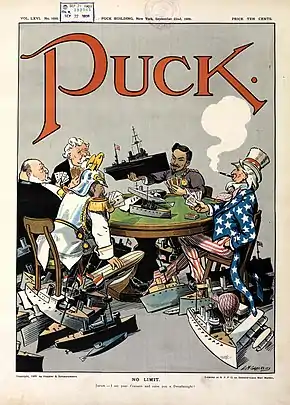

In this Allegory depicting the 1576 Pacification of Ghent by Adriaen Pietersz van de Venne, the seated women represent a short-lived unity among the embattled provinces of what would become the present-day Belgium and Netherlands 1909 cartoon in Puck shows (clockwise) US, Germany, Britain, France and Japan engaged in naval race in a "no limit" game.

1909 cartoon in Puck shows (clockwise) US, Germany, Britain, France and Japan engaged in naval race in a "no limit" game.

Personifications by country or territory

See also

- Afghanis-tan, a manga originally published as a webcomic about Central Asia with personified countries.

- Polandball, a contemporary form of national personification in which countries are drawn by Internet users as stereotypic balls and shared as comics on online communities.

- Hetalia: Axis Powers, an anime about personified countries interacting, mostly taking place within the World Wars.

- Mural crown

- National animal, often personifies a nation in cartoons.

- National emblem, for other metaphors for nations.

- National god, a deity that embodies a nation.

- National patron saint, a Saint that is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation.

References

- ↑ "Il Tempio di Venere e Roma" (in Italian). Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- ↑ Eric Hobsbawm, "Mass-Producing Traditions: Europe, 1870-1914," in Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger, eds., The Invention of Tradition (Cambridge, 1983), 263-307.

- ↑ Ahmed, Salahuddin (2004). Bangladesh: Past and Present. APH Publishing. p. 310. ISBN 8176484695. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ↑ "NATIONAL SYMBOLS". Bangladesh Tourism Board. Bangladesh: Ministry of Civil Aviation & Tourism. Archived from the original on 2016-12-28. Retrieved 2015-09-10.

- ↑ Couvreur, Manuel; Deknop, Anne; Symons, Thérèse (2005). Manneken-Pis : Dans tous ses états. Historia Bruxellae (in French). Vol. 9. Brussels: Musées de la Ville de Bruxelles. ISBN 978-2-930423-01-2.

- ↑ Emerson, Catherine (2015). Regarding Manneken Pis: Culture, Celebration and Conflict in Brussels. Leeds: Taylor & Francis Ltd. ISBN 978-1-909662-30-8.

- ↑ McGill, Robert (2017). War Is Here: The Vietnam War and Canadian Literature. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 37. ISBN 9780773551589. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ↑ Barber, Katherine (2007). Only in Canada You Say: A Treasury of Canadian Language. Oxford University Press Canada. p. 70. ISBN 9780195427073.

- ↑ "Library and Archives Canada". Library and Archives Canada.

- ↑ Hassanabadi, Mahmoud. "Rostam: A Complex Puzzle: A New Approach to the Identification of the Character of Rostam in the Iranian National Epos Shāhnāme".

- ↑ Dallmayr, Fred (25 August 1999). Border Crossings: Toward a Comparative Political Theory. ISBN 9780739152546.

- ↑ https://papyrus.bib.umontreal.ca/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1866/14232/Heck_Isabel_2003_memoire.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- ↑ O'Rourke Murphy, M. & MacKillop, J. (2006). An Irish Literature Reader: Poetry, Prose, Drama.

- ↑ Minahan, James B. (2009). The Complete Guide to National Symbols and Emblems. ABC-CLIO. p. 436. ISBN 9780313344978.

- ↑ Blashfield, Jean F. (2009). Italy. Scholastic. p. 33. ISBN 9780531120996.

- ↑ ""Saint Mark", Franciscan Media". Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ Yordan Zhelyazkov (February 12, 2021). "Amaterasu – Goddess, Mother and Queen". Symbolsage. Archived from the original on June 3, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ↑ Liok Ee Tan (1988). The Rhetoric of Bangsa and Minzu. Monash Asia Institute. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-86746-909-7.

- ↑ Melanie Chew (1999). The Presidential Notes: A biography of President Yusof bin Ishak. Singapore: SNP Publications. p. 78. ISBN 978-981-4032-48-3.

- ↑ Minahan, James B. (2009). The Complete Guide to National Symbols and Emblems. Greenwood. p. 101. ISBN 978-0313344961.

- ↑ Subba, Sanghamitra. "Love it or hate it, it's abominable".

- ↑ Phillips, Jock. "South African War memorial, Waimate".

- ↑ Dingwall, R. "Southern Man (Dunedin Airport)", Otago Sculpture Trust, 19 November 2011. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ↑ "A Manifesto from the Provisional Government of Macedonia". 1881.

Our mother Macedonia became now as a widow, lonely and deserted by her sons. She does not fly the banner of the victorious Macedonian army

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Bulgarian graphic representation of Bulgaria, East Rumelia and North Macedonia

- ↑ "Kunstschatten: Mama Sranan - Parbode Magazine". Archived from the original on 2016-04-14. Retrieved 2016-03-30.

- ↑ Valance, Marc. (Baden, 2013) Die Schweizer Kuh. Kult und Vermarktung eines nationalen Symbols, p. 6 ff.

Further reading

- Lionel Gossman. "Making of a Romantic Icon: The Religious Context of Friedrich Overbeck's 'Italia und Germania.'" American Philosophical Society, 2007. ISBN 0-87169-975-3.

%252C_Johann_Joachim_Kaendler_and_assistants%252C_Meissen_Porcelain_Factory%252C_c._1760%252C_hard-paste_porcelain_-_Wadsworth_Atheneum_-_Hartford%252C_CT_-_DSC05373.jpg.webp)

.jpeg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_Famiano_Strada_c1647.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)