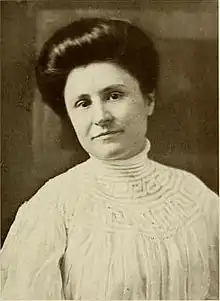

Clare Pfeifer Garrett (July 26, 1882 – May 15, 1946) was an American sculptor of considerable interest in St. Louis in the 1910s.

Early life

Garrett was born Clare Pfeifer on July 26, 1882,[1] in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the daughter of Carl Pfeifer, a prominent engineer, who took an important part in the erection of the Eads Bridge. When she was ten years old her father died at the age of forty. Both her parents were German-born, and came from Germany as children, the mother, Marie Rotteck, in 1848, and the father several years later. Her brother, H. J. Pfeifer, followed in his father's footsteps, was the engineer, maintenance of way, of the Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis.[2]

She studied in St. Louis and then went to Paris and New York. She attended the public schools of St. Louis and later was a pupil of Sacred Heart Convent. In 1906, while in London, she married Edmund A. Garrett, an artist and inventor. They had two sons, Carl and Julian, who were often models for their mother.[2]

St. Louis 1890–1902

At the age of eighteen she first attended classes at the art school in the old museum on Locust Street, where Robert P. Bringhurst was her first and the most efficient and painstaking instructor she ever had. Garrett related that she did nothing serious for the first year; she played and wasted her time, and it was not until the closing week of the term that she thought of her work other than as a diversion and a lark. Her lack of concentration annoyed Bringhurst and he became discouraged with her. "You had better give it up. You have no ability," he told her. "I have ability" she cried. "I will do this thing," pointing to a difficult model, "and I will finish it, too." This thoroughly aroused her slumbering energy and ambition. Her interest in her work became absorbing and she won scholarships as well as their first medal.[2]

Studying at the St. Louis School of Fine Arts from 1893 to 1897, she won scholarships, and in 1897 its prize medal. From that time until 1902 she maintained her own studio in St. Louis, where she became busy with her first commissions, and a number of large pieces, among them the already referred - to bust of President McKinley, in the McKinley High School, a fifty-foot frieze of children in the Eugene Field School (1901), and a memorial bas-relief at the Mary Institute.[2] According to Mary Powell in Public Art in St. Louis, the Eugene Field School frieze was still in place in 1925, but currently the piece is lost.[3]

For two years after finishing the course she lived an altogether social life, but tiring of it, finally fell back on her art, which occupied time that had come to lag heavily, and gave her an opportunity to express the latent talent she had allowed to lie dormant. The development of her art and the acquirement of an aim in life date from this period.[2]

Her first studio in St. Louis was in the Y. M. C. A. Building—for one year. And the first commission was from Mr. Ittner, the architect, for the frieze in the Eugene Field kindergarten.[2] She lived at 4128 Botanical Avenue, St. Louis.[4]

In St. Louis three of Garrett's large pieces could be seen at the Mary Institute, the Eugene Field School and McKinley High School. A fourth, posed by a St. Louis girl and named Carrie Kingsbury or Awakening of Spring (1902),[5] stands still today at the entrance of Kingsbury Place adorning the Union Boulevard gateway.[4] The Kingsbury piece took two years of work to Garrett and once unveiled, the sensual nudity of the girl caused such an uproar that Garrett used the $7000 ($236,762 in 2022 dollars) compensation to move to Paris. A number of smaller pieces were in many of St. Louis' finest homes. She was splendidly remunerated, busts bringing her $1,000 ($29,216 in 2022 dollars), and other pieces in proportion.

She acted as assistant to Bringhurst for several years, while studying in the art school, and spent some time in Omaha, assisting him in work on the pediment of the Art Building, under construction for the Fair.[2]

This included decorating cornices. Often she would work on scaffolding twelve feet high. Here an interesting incident took place. Garrett preferred modeling children wherever the opportunity presents itself, and made a number of very good nudes of little cherubs which were put on the cornices. One night, soon after, the Salvation Army women chopped them down with axes. They were heavily fined and obliged to pay for them. Their artistic point of view evidently did not coincide with that of the artist. This brought a great deal of notoriety at the time to both Bringhurst and his assistant.[2]

Paris 1902–1904

In 1902 Garrett was able to realize the cherished ambition of every aspiring artist, to study in Paris, where she entered L'Ecole des Beaux Arts, under Marquette and Mercié. This was the great French school, and was the greatest of art and architecture in the world. Afterwards, she left there for more advanced work, the study of her own models in her own studio. Emile Bourdelle, the French sculptor, renowned for great subtlety in his work, she chose as her critic. For the first year he came weekly, afterward only as Garrett sent for him. For each criticism his fee was 50 francs ($10) ($338 in 2022 dollars), from which we learn that not only is art long and life short, but that it is expensive, too.[2]

Her work was exhibited in the Salon, Champs Elysees, Paris, 1903–05, the three years she resided abroad. Les Crysalides was exhibited in the Royal Academy, London, 1904,[2] and again at the 101st Annual Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1906 hosted by the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts.[6]

Always in 1904 she was awarded a bronze medal by the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, held in St. Louis in 1904, for Echo, a bronze in the nude.

New York 1905–1915

A portrait in low-relief (bas-relief) of her husband was exhibited by the National Sculpture Society, New York, in 1905, and by it awarded honorable mention. Until her return from the East to St. Louis she was a regular exhibitor at the National Academy, and at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.[2] In New York she lived first at 15 E. 59th St, New York City,[6] and later at 993 E. 150th St., New York City.[7]

In 1906 her Boy Teasing a Turtle, a fountain figure exhibited in Paris at the Salon of 1903 and at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, in 1904, was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.[1] It was purchased by Sir Caspar Purdon Clarke, the director of the museum, from the Gorham Company, Fifth Avenue, New York, through whom Garrett sold her smaller pieces exclusively.[2] Always in 1906 she exhibited 3 pieces at the National Academy of Design 81st exhibition held at 215 West 57th Street, New York City: Lorette, Mrs. B. and her daughter, Madame C. et sa fille.[8]

In 1907 she exhibited three pieces at the Boston Art Club fine arts exhibition: Statuette of a Little Girl, The Naiade (statuette) and Portrait in Relief.[7]

In 1908 she exhibited one piece, My son, at the National Academy of Design during their 83rd Annual Exhibition.[9]

Her husband had a collection of platinum-print photographs of his wife's many pieces of work, pieces that were sold and scattered from New York to California. Among them, not already mentioned, was one which carried a strong appeal, Budding Womanhood, owned by David Belasco; a medallion portrait relief of Mrs. Hudson E. Bridge, and a life-size group of a French lady with her young daughter.[2]

Another was The Peasant Boy, which she sold to Gorham & Co., silversmiths. The Boy Piper and Sleep were figures in the Strauss photograph gallery in St. Louis. A model for a clock, which attracted much attention, was made for Mrs. James Blair.[2]

St. Louis 1915–1929

In 1915 she obtained the sculpture prize of the Artists' Guild of St. Louis and in 1916 the St. Louis Art League prize of $500 ($13,446 in 2022 dollars) with the sculpture Mother and Daughter.[4][10]

In 1915 Dr. Frank J. Lutz retired. He built up the St. Louis Medical Library later Library of the St. Louis Medical Society. In recognition of this service the society accepted a life-size bronze medallion of Dr. Lutz presented by members of the society in 1916. The members subscribed a minimum of one dollar each. They collected $163. Clara Pfeifer Garrett offered to make the medallion for $150. The model was completed on February 14, 1915, and accepted by the committee. It was then sent to New York and cast in bronze by the Gorham Company. On its return to St. Louis Garrett asked the privilege of entering the medallion in competition in the second annual Open Competitive Exhibition of the St. Louis Artists Guild. The committee, with the consent of Dr. Lutz, granted the request and the tablet won the first prize in sculpture, the Susan Rebecca Carleton prize of $100. In the Bulletin of the St. Louis Art League, Vol. 11, No. 2, is a photograph of the tablet and in a review of the exhibition: "Mrs. Garrett in her tablet to Dr. Frank J. Lutz shows praiseworthy capacity to carry a serious sculptural work through to completion in a thoroughly workmanlike manner."[11]

Beverly Hills 1929–1941

From 1929 to 1941 Garrett lived in Beverly Hills, California.[12]

Later life and death

She died on May 15, 1946, in New York City.[13]

Slides of Clara Pfeiffer Garrett's sculptures are available in the Garrett Family Papers, ca. 1860–1979 at University of Wyoming, American Heritage Center.[14]

References

- 1 2 Gardner, Albert TenEyck (1965). American Sculpture: A Catalogue of the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 146. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Johnson, Anne (1914). Notable women of St. Louis, 1914. St. Louis, Woodward. p. 76. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form" (PDF). United States Department of the Interior National Park Service. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Woman Who Won Grand Prize at St. Louis Salon and Her Sculpture on Which Award Was Made - 16 Apr 1916, Sun • Page 54". St. Louis Post-Dispatch: 54. 1916. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ↑ Peters, Frank (1989). A Guide to the Architecture of St. Louis. University of Missouri Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780826206794. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- 1 2 texts Catalogue of the ... annual exhibition. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. 1906. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- 1 2 texts Boston Art Club fine arts exhibition. Boston Art Club. 1907. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ↑ texts Annual exhibition - National Academy of Design. National Academy of Design. 1906. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ↑ texts Annual exhibition - National Academy of Design. National Academy of Design. 1908. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ↑ American Art Annual, Volume 28; Volume 30. MacMillan Company. 1931. p. 526. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ↑ texts Journal of the Missouri State Medical Association. Missouri State Medical Association. 1916. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ↑ Reuter, F. Turner (2008). Animal & sporting artists in America. National Sporting Library. p. 269. ISBN 9780979244100. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ↑ "Garret, Clara Pfeifer - 25 May 1946, Sat • Page 8". St. Louis Post-Dispatch: 8. 1946. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ↑ Papers, ca. 1860-1979. OCLC 31912646. Retrieved 29 January 2018 – via WorldCat.