| Classical Guarani | |

|---|---|

| Missionary Guarani, Old Guarani | |

| abá ñeȇ́ | |

| |

| Pronunciation | [ʔaʋaɲẽˈʔẽ] |

| Native to | Paraguay, Argentina, Brazil |

| Region | Jesuit missions among the Guaraní |

| Ethnicity | Guaraní, Jesuit missionaries |

| Era | 16th century – 18th century AD |

Tupian

| |

| Guarani alphabet (Latin script) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | oldp1258 |

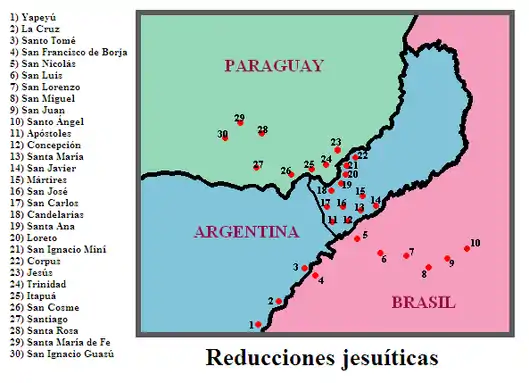

Map of the Jesuit reductions among the Guarani | |

Classical Guarani, also known as Missionary Guarani or Old Guarani (abá ñeȇ́ lit. 'the people's language') is an extinct variant of the Guarani language. It was spoken in the region of the thirty Jesuit missions among the Guarani (current territories of Paraguay, Argentina and Brazil). The Jesuits studied the language for around 160 years, assigning it a writing system and consolidating several dialects into one unified language.[1] Classical Guarani went extinct gradually after their suppression in 1767.

Despite its extinction, its bibliographical production and that of written documents was rich and is still mostly conserved.[2] Therefore, it is considered an important literary branch in the history of Guarani.

Shift from Classical to Criollo

Criollo Guarani has its roots in the Classical Guarani as spoken outside Jesuit missions, once the Society of Jesus was suppressed. Modern scholars have shown that Guarani has always been the main language of the Jesuit Guarani missions and, later on, to the whole Governorate of Paraguay which belonged to the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata.

After the expulsion of the Jesuits, the residents of the reductions emigrated gradually towards territories of current Paraguay, Corrientes, Uruguay, Entre Ríos and those to the North of Río Salado. These migratory moves caused a one-sided change in the language, making it stray far from the original dialect that the Jesuits had studied.[3][4]

Classical Guarani kept away from Hispanicisms, favoring the use of the language's agglutinative nature to coin new terms. This process would often lead to the Jesuits using more complex and synthetic terms to transmit Western concepts. Criollo Guarani, on the other hand, has been characterized by a free influx, unregulated with regards to Hispanicisms which were often incorporated with a minimal phonological adaptation. Thus, the word for communion in Classical Guarani would be Tȗpȃ́rára whereas in Criollo Guarani it is komuño (from Spanish comunión).[5]

Because of the emigration from the reductions, Classical and Criollo got to come to a wide contact with each other. Most speakers abandoned the Classical variant, more complicated and with more rules, in favor of the more practical Criollo.

Phonology

Consonants

The consonant phonemes of Classical Guarani are as follows:

| Labial | Alveolar | Alveolo-palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | lab. | ||||||

| Stop | Voiceless | p | t~ⁿt | k | kʷ | ʔ | |

| Voiced | ᵐb~m | ⁿd~n | ᵈj~ɲ | ᵑɡ~ŋ | ᵑɡʷ~ŋʷ | ||

| Fricative | s | ɕ~ʃ | x ~ h | ||||

| Approximant | ʋ | ɰ ~ ɰ̃ | w ~ w̃ | ||||

| Flap | ɾ | ||||||

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Close | oral | i | ɨ | u |

| nasal | ĩ | ɨ̃ | ũ | |

| Open | oral | e | a | o |

| nasal | ẽ | ã | õ | |

Orthography

Classical Guarani using letters from the Latin alphabet assigned to each phoneme by Jesuit missionaries.

| Grapheme | a | ȃ | b | c | ch | ç | e | ȇ | g | h | i | ȋ | ĭ | m | mb | n | nd | ng | nt | ñ | o | ȏ | p | qu | r | t | u | ȗ | y | ỹ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phoneme | a | ã | ʋ | s (before e, i) k (before a, o, u) | ɕ~ʃ | s | e | ẽ | ɰ | x ~ h | i | ĩ | ɨ | m | ᵐb | n | ⁿd | ᵑɡ, ŋ | ⁿt | ɲ | o | õ | p | kʷ, k | ɾ | t | u | ũ | ʝ, j | ɨ̃ |

Some of the orthographical rules are as follows:[6]

- c is read as /k/ before a, o and u. It is read as /s/ before e and i. ç is used only before the vowels where c would otherwise be read as /k/ (ço /so/ to avoid co /ko/).

- qu is read as /k/ before e and i and as /kʷ/ before a, in which case it always forms a diphthong or triphthong (e.g. que /ke/, tequay /teˈkʷaj/).

- Syllables with ĭ and ỹ are always stressed.

- Syllables ending in ĭ and ỹ are always oxytones.

- Syllables with circumflex accents are always stressed.

- Two vowels next to each other are separated by a glottal stop unless a circumflex accent is added to form a diphthong in which case the syllable is always stressed unless specified otherwise (e.g. cue is read as /kuˈʔe/ while cuê is read as /kʷe/)

Early scholars failed to represent the glottal stop. This is due to the prevailing view at the time among scholars (which lasted until the sixties) that the glottal stop in Guarani was a suprasegmental phenomenon (hiatus, stress, syllable, etc.).[7]

Numbers

Classical Guarani only had four numbers on its own. Bigger numbers were introduced later on in the rest of Guarani languages.

| peteȋ́, moñepeteȋ́, moñepê, moñepeȋ́ | one | |

| mȏcȏî | two | |

| mbohapĭ | three | |

| yrundĭ | four | |

| mbo mȏcȏî ya catú | ten |

Sometimes they used yrundĭ hae nirȗî or ace pópeteȋ́ 'one human hand' for five, ace pómȏcȏî 'two human hands' for ten and mbó mbĭ abé 'hands and also feet' or ace pó ace pĭ abé 'human hands and also human feet' for twenty.[8]

Grammar

Many nouns and verbs in its most basic form ("root") ended in consonants. However, the language did not allow lexemes to end in consonants. Therefore this form was never used alone by itself in speech but existed only hypothetically. It was, however, used accompanied by suffixes. For dictionaries and other books with the purpose of studying the language, this form was written with the last consonant between two full stops (e.g. tú.b. is the root, túba is the nominative).

The language had no gender and no number as well. If an emphasis was to be made, they used words such as hetá (many) or specified the cardinal number.

Example text

Act of Contrition from Catecismo de la lengua guaraní, the first catechism in Guarani, by Friar Antonio Ruiz de Montoya.

Hae oȃngaipapaguê mboaçĭpa nateí. Cheyara Ieſu Chriſto Tȗpȃ́ eté Aba eté abé eicóbo, amboaçĭ chepĭ á guibé, ndebe cheangaipá haguêra nde Tȗpȃ́ etérȃmȏ nderecó rehé, che nde raĭhú rehé mbaepȃbȇ́ açoçé abé. Tapoí coĭterȏ́ che angaipábaguî, tañêmombeû Paí vpé, nde ñỹrȏ́ angá chébe, nde remȋ́mborará rehé, ndereȏ́ rehé abé. Amen Ieſus.

References

- ↑ Fernández, Manuel F. (2002). "Breve historia del guaraní" (PDF). Datamex. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-29. Retrieved 2008-05-22.

- ↑ Ministry of Foreign Affairs (October 2012). "La lengua guaraní del Paraguay" (PDF). Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-25.

- ↑ Wilde, Guillermo (2001). "Los guaraníes después de la expulsión de los jesuitas: dinámicas políticas y transacciones simbólicas". Revista Complutense de Historia de América (27). doi:10.5209/rcha/crossmark. ISSN 1132-8312.

- ↑ Telesca, Ignacio (2009-10-22). "Tras los Expulsos. Cambios demográficos y territoriales en el Paraguay después de la expulsión de los jesuitas". Nuevo Mundo, Mundos Nuevos. doi:10.4000/nuevomundo.57310. ISSN 1626-0252. Archived from the original on 2022-10-20. Retrieved 2022-10-20.

- ↑ Ruiz de Montoya, Antonio (1640). Catecismo de la lengua guaraní. Buenos Aires: Centro de Estudios Paraguayos "Antonio Guasch" (CEPAG). ISBN 978-99953-49-11-0. OCLC 801635983.

- ↑ Ruiz de Montoya, Antonio (1639). Tesoro de la lengua guaraní. Centro de Estudios Paraguayos "Antonio Guasch" (CEPAG). ISBN 978-99953-49-09-7. OCLC 801635986. Archived from the original on 2023-04-23. Retrieved 2022-10-25.

- ↑ Penner, Hedy (2020-12-23). "Gestión glotopolítica del Paraguay: ¿Primero normativizar, después normalizar?". Caracol (in Spanish) (20): 232–269. doi:10.11606/issn.2317-9651.i20p232-269. ISSN 2317-9651. S2CID 234408992. Archived from the original on 2022-10-25. Retrieved 2022-10-25.

- ↑ Ruiz de Montoya, Antonio (1640). Arte y vocabulario de la lengua guaraní. Cultura Hispánica. ISBN 84-7232-728-0. OCLC 434440201.