| Classics Club | |

|---|---|

| Founder | Marcel Rodd |

| Status | Defunct |

| Country of origin | UK |

Classics Club was a British record label which was active between 1956 and 1964. It was a pioneer in the release of low-cost classical music LP records marketed direct to the public though a record club.

The label was established by Marcel Rodd (1912–98) who had emigrated to the US and prospered as a publisher selling books by mail-order in California in the 1940s.[1] On return to London in 1955, he formed an independent record label, Allied Records Ltd, originally to press and distribute a catalogue of nursery rhymes and bedtime stories.[2] A disused chapel at 127 Kensal Road was converted into a record factory with lacquer cutting lathes and record presses able to turn master tapes into mass-produced LPs.

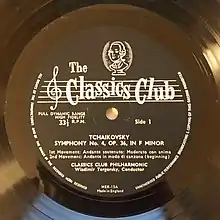

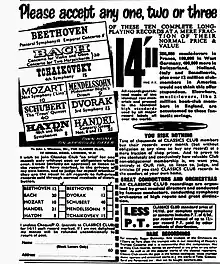

In October 1956, Rodd licensed recordings from US companies Urania and the Concert Hall Society, registering a second company, Art & Sound Ltd, to hold the rights to his growing library of tapes. He used a pseudonym (John Winstone) as director of yet another company, Record Sales Ltd, which issued the LPs on the Classics Club label. Members were offered a monthly selection of titles and undertook to purchase a minimum number.[3] Most of these Classics Club releases were credited to the Classics Club Symphony (or Philharmonic) Orchestra, with the implication that they were recorded exclusively for the members, though none of the named orchestras or conductors existed. For example, sessions conducted by Walter Goehr were credited to a fictional “Wladimir Tergorsky”—where the true name is hinted at in the pseudonym.[4]

Classics Club first advertised in The Listener of 27 June 1957 and subsequently submitted advertising copy to the respected Gramophone magazine, but its editor, Compton Mackenzie, refused it. Rodd fought back by placing an advertorial in the weekly Truth magazine in the form of a letter by "Dorothy Whistler", another pseudonym, entitled The Gramophone bans Classic Club ads and served to raise the label's profile.[5] Truth's reviewer, the critic Trevor Gee, subsequently wrote:

I have listened to some of the 10in. LP orchestral discs sold by Classics Club ... at the amazingly low price of 14s 11d. There is no catch in it: the listener gets precisely 14s worth of value. Performances are mostly by artists with unfamiliar names, who may or may not be well-known players hiding under pseudonyms, musically adequate but no more and recorded with a conspicuous shallowness of tone not always well focused nor balanced.[6]

At first, Rodd created the sleeve notes from reference books, so when an early subscriber, Frederick Youens, complained about their poor quality he was invited to take them on himself. He also toured local gramophone societies promoting the label.[7]

By now there were several subscription record clubs active in Britain, notably the World Record Club. They followed the same model of offering LP recordings of popular classical works at discounted prices, which they achieved by selling direct to members by mail order and by sourcing older recordings under licence. Reports suggested that record clubs helped to stimulate interest in classical music and increase sales overall.[8] Decca responded to these new low-price competitors with its Ace of Clubs label in June 1958.

Rodd's next move was to create a catalogue of recordings that he owned outright. His budget allowed only minimal session time and little editing, so there was no studio producer before the 1970s.

In 1960 the Concert Hall Society set up its own UK branch, the Concert Hall Record Club, offering "3 LP records of your choice for only 6/-", and the Classics Club label was to lose the substantial part of its catalogue that was licensed from them.[9] At this point, Rodd was able to acquire the assets of the failing Saga Records label, specifically its library of master tapes, in exchange for a quantity of LPs pressed specially for the occasion by Allied Records.

A postal workers’ dispute at the end of 1961[10] further affected the mail-order business, requiring costs to be cut and the “Club News” written by Frederick Youens, which had developed into quite an informative magazine, came to an abrupt end. In its place an unadorned monthly release sheet gradually turned into an increasingly desperate series of special offers. Concert Hall Record Club, which had hardly begun when it was hit by the dispute, offered good quality Philips vinyl in colourful sleeves with decent notes and took much of the market. Classics Club's final issues were announced in “Club News” No.102 in June 1964.[3]

References

- ↑ Marcel Rodd Company (1944). Catalog. Hollywood (Los Angeles, Calif.): The Marcel Rodd Company. OCLC 988950097.

- ↑ "Allied Records Ltd". Discogs. Retrieved 2021-04-23.

- 1 2 Stuart, Philip (2017). Classics Club/Saga 1956-1986 A discographical adventure. Sheffield, UK: CRQ Editions. p. 6.

- ↑ "Walter Goehr | Damian's 78s (and a few early LPs)". Retrieved 2021-04-23.

- ↑ Whistler, Dorothy (8 Nov 1957). "The Gramophone bans Classics Club ads". Truth.

- ↑ Gee, Trevor (15 Nov 1957). "Records". Truth.

- ↑ "Chesham Gramophone Society". Buckinghamshire Examiner. 23 Oct 1959.

- ↑ Curran, Terrence W. (2015). Recording classical music in Britain: The long 1950s (DPhil in Music). CRQ Editions.

- ↑ "Concert Hall Record Club". Daily Mirror. 12 Sep 1961. p. 12.

- ↑ "Post Office Employees Dispute (1962)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 23 January 1962. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- Stuart, Philip (2017). Classics Club / Saga 1956-1986 A discographical adventure. Sheffield: Classical Recordings Quarterly Editions.