| Clathrin heavy N-terminal propeller repeat | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Clathrin terminal domain | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Clathrin_propel | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF01394 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0020 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR022365 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1bpo / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Clathrin heavy-chain linker | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

clathrin heavy chain proximal repeat (linker) | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Clathrin-link | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF09268 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0020 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR015348 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1b89 / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| CHCR/VPS 7-fold repeat | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Clathrin_propel | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00637 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0020 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR000547 | ||||||||

| SMART | SM00299 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PS50236 | ||||||||

| CATH | 1b89 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1b89 / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Clathrin light chain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Clathrin_lg_ch | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF01086 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR000996 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00196 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 3iyv / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

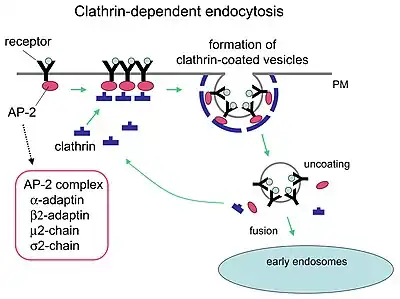

Clathrin is a protein that plays a major role in the formation of coated vesicles. Clathrin was first isolated by Barbara Pearse in 1976.[1] It forms a triskelion shape composed of three clathrin heavy chains and three light chains. When the triskelia interact they form a polyhedral lattice that surrounds the vesicle. The protein's name refers to this lattice structure, deriving from Latin clathri meaning lattice.[2] Barbara Pearse named the protein clathrin at the suggestion of Graeme Mitchison, selecting it from three possible options.[3] Coat-proteins, like clathrin, are used to build small vesicles in order to transport molecules within cells. The endocytosis and exocytosis of vesicles allows cells to communicate, to transfer nutrients, to import signaling receptors, to mediate an immune response after sampling the extracellular world, and to clean up the cell debris left by tissue inflammation. The endocytic pathway can be hijacked by viruses and other pathogens in order to gain entry to the cell during infection.[4]

Structure

| Clathrin light chain a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | CLTA | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 1211 | ||||||

| HGNC | CLTA. HGNC:2090. CLTA. | ||||||

| UniProt | P09496 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| Locus | Chr. 9 q13 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Clathrin light chain b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | CLTB | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 1212 | ||||||

| HGNC | 2091 | ||||||

| OMIM | 118970 | ||||||

| RefSeq | NM_001834 | ||||||

| UniProt | P09497 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| Locus | Chr. 5 q35 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Clathrin heavy chain 1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | CLTC | ||||||

| Alt. symbols | CHC, CHC17, CLTCL2 | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 1213 | ||||||

| HGNC | 2092 | ||||||

| OMIM | 118955 | ||||||

| RefSeq | NM_004859 | ||||||

| UniProt | Q00610 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| Locus | Chr. 17 q23.1-qter | ||||||

| |||||||

| Clathrin heavy chain 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | CLTCL1 | ||||||

| Alt. symbols | CLTCL | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 8218 | ||||||

| HGNC | 2093 | ||||||

| OMIM | 601273 | ||||||

| RefSeq | NM_001835 | ||||||

| UniProt | P53675 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| Locus | Chr. 22 q11.21 | ||||||

| |||||||

The clathrin triskelion is composed of three clathrin heavy chains interacting at their C-termini, each ~190 kDa heavy chain has a ~25 kDa light chain tightly bound to it. The three heavy chains provide the structural backbone of the clathrin lattice, and the three light chains are thought to regulate the formation and disassembly of a clathrin lattice. There are two forms of clathrin light chains, designated a and b. The main clathrin heavy chain, located on chromosome 17 in humans, is found in all cells. A second clathrin heavy chain gene, on chromosome 22, is expressed in muscle.[5]

Clathrin heavy chain is often described as a leg, with subdomains, representing the foot (the N-terminal domain), followed by the ankle, distal leg, knee, proximal leg, and trimerization domains. The N-terminal domain consists of a seven-bladed β-propeller structure. The other domains form a super-helix of short alpha helices. This was originally determined from the structure of the proximal leg domain that identified and is composed of a smaller structural module referred to as clathrin heavy chain repeat motifs. The light chains bind primarily to the proximal leg portion of the heavy chain with some interaction near the trimerization domain. The β-propeller at the 'foot' of clathrin contains multiple binding sites for interaction with other proteins.[5]

When triskelia assemble together in solution, they can interact with enough flexibility to form 6-sided rings (hexagons) that yield a flat lattice, or 5-sided rings (pentagons) that are necessary for curved lattice formation. When many triskelions connect, they can form a basket-like structure. The structure shown, is built of 36 triskelia, one of which is shown in blue. Another common assembly is a truncated icosahedron. To enclose a vesicle, exactly 12 pentagons must be present in the lattice.

In a cell, clathrin triskelion in the cytoplasm binds to an adaptor protein that has bound membrane, linking one of its three feet to the membrane at a time. Clathrin cannot bind to membrane or cargo directly and instead uses adaptor proteins to do this. This triskelion will bind to other membrane-attached triskelia to form a rounded lattice of hexagons and pentagons, reminiscent of the panels on a soccer ball, that pulls the membrane into a bud. By constructing different combinations of 5-sided and 6-sided rings, vesicles of different sizes may assemble. The smallest clathrin cage commonly imaged, called a mini-coat, has 12 pentagons and only two hexagons. Even smaller cages with zero hexagons probably do not form from the native protein, because the feet of the triskelia are too bulky.[6]

Function

Clathrin performs critical roles in shaping rounded vesicles in the cytoplasm for intracellular trafficking. Clathrin-coated vesicles (CCVs) selectively sort cargo at the cell membrane, trans-Golgi network, and endosomal compartments for multiple membrane traffic pathways. After a vesicle buds into the cytoplasm, the coat rapidly disassembles, allowing the clathrin to recycle while the vesicle gets transported to a variety of locations.

Adaptor molecules are responsible for self-assembly and recruitment. Two examples of adaptor proteins are AP180[7] and epsin.[8][9][10] AP180 is used in synaptic vesicle formation. It recruits clathrin to membranes and also promotes its polymerization. Epsin also recruits clathrin to membranes and promotes its polymerization, and can help deform the membrane, and thus clathrin-coated vesicles can bud. In a cell, a triskelion floating in the cytoplasm binds to an adaptor protein, linking one of its feet to the membrane at a time. The triskelion foot will bind to other ones attached to the membrane to form a polyhedral lattice, triskelion foot, which pulls the membrane into a bud. The foot does not bind directly to the membrane, but binds to the adaptor proteins that recognize the molecules on the membrane surface.

Clathrin has another function aside from the coating of organelles. In non-dividing cells, the formation of clathrin-coated vesicles occurs continuously. Formation of clathrin-coated vesicles is shut down in cells undergoing mitosis. During mitosis, clathrin binds to the spindle apparatus, in complex with two other proteins: TACC3 and ch-TOG/CKAP5. Clathrin aids in the congression of chromosomes by stabilizing kinetochore fibers of the mitotic spindle. The amino-terminal domain of the clathrin heavy chain and the TACC domain of TACC3 make the microtubule binding surface for TACC3/ch-TOG/clathrin to bind to the mitotic spindle. The stabilization of kinetochore fibers requires the trimeric structure of clathrin in order to crosslink microtubules.[11][12][13]

Clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) regulates many cellular physiological processes such as the internalization of growth factors and receptors, entry of pathogens, and synaptic transmission. It is believed that cellular invaders use the nutrient pathway to gain access to a cell's replicating mechanisms. Certain signalling molecules open the nutrients pathway.[1] Two chemical compounds called Pitstop 1 and Pitstop 2, selective clathrin inhibitors, can interfere with the pathogenic activity, and thus protect the cells against invasion. These two compounds selectively block the endocytic ligand association with the clathrin terminal domain in vitro.[14] However, the specificity of these compounds to block clathrin-mediated endocytosis has been questioned.[15] In later studies, however, the specificity of Pitstop 2 was validated as being clathrin dependent.[16]

See also

References

- 1 2 Pearse BM (April 1976). "Clathrin: a unique protein associated with intracellular transfer of membrane by coated vesicles". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 73 (4): 1255–1259. Bibcode:1976PNAS...73.1255P. doi:10.1073/pnas.73.4.1255. PMC 430241. PMID 1063406.

- ↑ "clathrate, adjective". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ↑ Pearse BM (September 1987). "Clathrin and coated vesicles". EMBO J. 6 (9): 2507–12. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02536.x. PMC 553666. PMID 2890519.

- ↑ "InterPro". Archived from the original on 2016-01-16. Retrieved 2015-10-07.

- 1 2 Robinson MS (December 2015). "Forty Years of Clathrin-coated Vesicles". Traffic. 16 (12): 1210–38. doi:10.1111/tra.12335. PMID 26403691.

- ↑ Fotin A, Kirchhausen T, Grigorieff N, Harrison SC, Walz T, Cheng Y (December 2006). "Structure determination of clathrin coats to subnanometer resolution by single particle cryo-electron microscopy". J Struct Biol. 156 (3): 453–60. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2006.07.001. PMC 2910098. PMID 16908193.

- ↑ McMahon HT. "Clathrin and its interactions with AP180". MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology. Archived from the original on 2009-05-01. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

micrographs of clathrin assembly

- ↑ McMahon HT. "Epsin 1 EM gallery". MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology. Archived from the original on 2009-01-02. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

micrographs of vesicle budding

- ↑ Ford MG, Pearse BM, Higgins MK, Vallis Y, Owen DJ, Gibson A, et al. (February 2001). "Simultaneous binding of PtdIns(4,5)P2 and clathrin by AP180 in the nucleation of clathrin lattices on membranes" (PDF). Science. 291 (5506): 1051–1055. Bibcode:2001Sci...291.1051F. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.407.6006. doi:10.1126/science.291.5506.1051. PMID 11161218. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-11-21. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- ↑ Higgins MK, McMahon HT (May 2002). "Snap-shots of clathrin-mediated endocytosis" (PDF). Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 27 (5): 257–263. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(02)02089-3. PMID 12076538. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-11-21. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- ↑ Royle SJ, Bright NA, Lagnado L (April 2005). "Clathrin is required for the function of the mitotic spindle". Nature. 434 (7037): 1152–1157. Bibcode:2005Natur.434.1152R. doi:10.1038/nature03502. PMC 3492753. PMID 15858577.

- ↑ Hood FE, Williams SJ, Burgess SG, Richards MW, Roth D, Straube A, et al. (August 2013). "Coordination of adjacent domains mediates TACC3-ch-TOG-clathrin assembly and mitotic spindle binding". The Journal of Cell Biology. 202 (3): 463–478. doi:10.1083/jcb.201211127. PMC 3734082. PMID 23918938.

- ↑ Prichard KL, O'Brien NS, Murcia SR, Baker JR, McCluskey A (2022-01-18). "Role of Clathrin and Dynamin in Clathrin Mediated Endocytosis/Synaptic Vesicle Recycling and Implications in Neurological Diseases". Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 15: 754110. doi:10.3389/fncel.2021.754110. PMC 8805674. PMID 35115907.

- ↑ Role of the Clathrin Terminal Domain in Regulating Coated Pit Dynamics Revealed by Small Molecule Inhibition|Cell, Volume 146, Issue 3, 471-484, 5 August 2011 Abstract Archived 2012-01-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Dutta D, Williamson CD, Cole NB, Donaldson JG (Sep 2012). "Pitstop 2 is a potent inhibitor of clathrin-independent endocytosis". PLOS ONE. 7 (9): e45799. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...745799D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045799. PMC 3448704. PMID 23029248.

- ↑ Robertson MJ, Horatscheck A, Sauer S, von Kleist L, Baker JR, Stahlschmidt W, et al. (November 2016). "5-Aryl-2-(naphtha-1-yl)sulfonamido-thiazol-4(5H)-ones as clathrin inhibitors". Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry. 14 (47): 11266–11278. doi:10.1039/C6OB02308H. PMID 27853797.

Further reading

- Wakeham DE, Chen CY, Greene B, Hwang PK, Brodsky FM (October 2003). "Clathrin self-assembly involves coordinated weak interactions favorable for cellular regulation". The EMBO Journal. 22 (19): 4980–4990. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdg511. PMC 204494. PMID 14517237.

- Ford MG, Mills IG, Peter BJ, Vallis Y, Praefcke GJ, Evans PR, McMahon HT (September 2002). "Curvature of clathrin-coated pits driven by epsin". Nature. 419 (6905): 361–366. Bibcode:2002Natur.419..361F. doi:10.1038/nature01020. PMID 12353027. S2CID 4372368.

- Fotin A, Cheng Y, Sliz P, Grigorieff N, Harrison SC, Kirchhausen T, Walz T (December 2004). "Molecular model for a complete clathrin lattice from electron cryomicroscopy". Nature. 432 (7017): 573–579. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..573F. doi:10.1038/nature03079. PMID 15502812. S2CID 4396282.

- Mousavi SA, Malerød L, Berg T, Kjeken R (January 2004). "Clathrin-dependent endocytosis". The Biochemical Journal. 377 (Pt 1): 1–16. doi:10.1042/BJ20031000. PMC 1223844. PMID 14505490.

- Smith CJ, Grigorieff N, Pearse BM (September 1998). "Clathrin coats at 21 A resolution: a cellular assembly designed to recycle multiple membrane receptors". The EMBO Journal. 17 (17): 4943–4953. doi:10.1093/emboj/17.17.4943. PMC 1170823. PMID 9724631. (Model of Clathrin assembly)

- Pérez-Gómez J, Moore I (March 2007). "Plant endocytosis: it is clathrin after all". Current Biology. 17 (6): R217–R219. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.045. PMID 17371763. S2CID 17680351. (Review on involvement of clathrin in plant endocytosis)

- Royle SJ, Bright NA, Lagnado L (April 2005). "Clathrin is required for the function of the mitotic spindle". Nature. 434 (7037): 1152–1157. Bibcode:2005Natur.434.1152R. doi:10.1038/nature03502. PMC 3492753. PMID 15858577.

- Hood FE, Williams SJ, Burgess SG, Richards MW, Roth D, Straube A, et al. (August 2013). "Coordination of adjacent domains mediates TACC3-ch-TOG-clathrin assembly and mitotic spindle binding". The Journal of Cell Biology. 202 (3): 463–478. doi:10.1083/jcb.201211127. PMC 3734082. PMID 23918938.

- Knuehl C, Chen CY, Manalo V, Hwang PK, Ota N, Brodsky FM (December 2006). "Novel binding sites on clathrin and adaptors regulate distinct aspects of coat assembly". Traffic. 7 (12): 1688–1700. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00499.x. PMID 17052248. S2CID 19087208.

- Edeling MA, Smith C, Owen D (January 2006). "Life of a clathrin coat: insights from clathrin and AP structures". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 7 (1): 32–44. doi:10.1038/nrm1786. PMID 16493411. S2CID 19393938.

- Dutta D, Williamson CD, Cole NB, Donaldson JG (Sep 2012). "Pitstop 2 is a potent inhibitor of clathrin-independent endocytosis". PLOS ONE. 7 (9): e45799. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...745799D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045799. PMC 3448704. PMID 23029248.

External links

- MBInfo - Clathrin Mediated Endocytosis

- Eukaryotic Linear Motif resource motif class LIG_Clathr_ClatBox_1

- Eukaryotic Linear Motif resource motif class LIG_Clathr_ClatBox_2

- Clathrin structure

- Membrane Dynamics

- Clathrin Dynamics ASCB Image & Video Library