| Clidastes | |

|---|---|

| Skeleton formerly referred to C. liodontus (AMNH FR 192) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Superfamily: | †Mosasauroidea |

| Family: | †Mosasauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Mosasaurinae |

| Genus: | †Clidastes Cope, 1868 |

| Species | |

| |

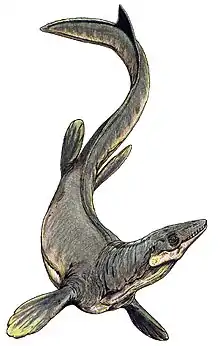

Clidastes is an extinct genus of marine lizard belonging to the mosasaur family. It is classified as part of the Mosasaurinae subfamily, alongside genera like Mosasaurus and Prognathodon. Clidastes is known from deposits ranging in age from the Coniacian to the early Campanian in the United States.

Clidastes means "locked vertebrae", which originates from the Greek noun κλειδί, or kleid meaning key (akin to Latin claudere meaning to shut). This refers to how the vertebral processes allow the proximal heads of the vertebrae to interlock for stability and strength during swimming.

It was one of the earliest hydropedal[note 1] mosasaurs, representing one of the first properly marine predatory forms alongside other early hydropedal genera like Tylosaurus and Platecarpus.[1] It was likely an agile swimmer that preyed upon cephalopods, fish and other small vertebrates in shallow water. Isotopic analysis on teeth specimens has suggested that this genus and Platecarpus may have entered freshwater occasionally, just like modern sea snakes.[2]

Description

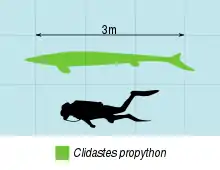

Clidastes was the one of the smallest of the mosasaurs (the smallest known being Dallasaurus), averaging 2–4 meters (6.6–13.1 ft) in length, with the largest specimens reaching 6.2 meters (20 feet) long.[3] The generic name refers to how the vertebral processes allow the proximal heads of the vertebrae to interlock for stability and strength during swimming. Even though the vertebrae lock together, the living animal would have still had a range of motion in the horizontal plane that is sufficient to allow for the high quality of swimming in shallow waters.[4] Additionally the strengthening of the tail, and entire backbone, allowed for muscle attachments to help it swimming. It possessed a delicate and slim form with an expansion of the neural spines and chevrons near the tip of the tail and this enabled it to chase down the fastest of prey.

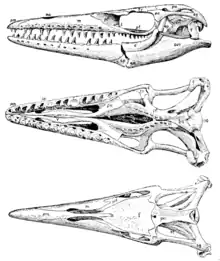

Due to being a well-represented and well-studied genus, Russell (1967)[5] could list a large range of unambiguous character states for the genus, including the following: "Premaxilla with or without small rostrum anterior to premaxillary teeth. Fourteen to eighteen teeth in maxilla. Prefrontal forms small portion of posterolateral border of external nares, broad triangular ala projects laterally from supraorbital wing. Prefrontal and postorbitofrontal widely separated above orbits. Lateral margins of frontal nearly straight and converge anteriorly, median dorsal ridge weak. Ventral process of postorbitofrontal to jugal confluent with broadly exposed dorsal surface of postorbitofrontal. No ventroposterior process on jugal. Parietal foramen small, located entirely within parietal. Margins of dorsal parietal surface parallel one another and cranial midline to posterior base of diverging suspensorial rami, forming narrow rectangular field medially on parietal. Squamosal sends abbreviated wing medially to contact ramus irom parietal. Otosphenoidal crest on prootic covers exit for cranial nerve VII laterally. Fourteen to sixteen teeth in pterygoid. Suprastapedial process of quadrate moderately large; tympanic ala very thick. Stapcdial pit elliptical in form. Sixteen-18 teeth in dentary. Small projection of dentary aritcrior to first dentary tooth. Medial wing Irom angular contacts or nearly contacts coronoid. Dorsal. edge of surangular very thin Iamina of bone rising anteriorly to position high on posterior surface of coronoid. Retroarticular process of articular triangular in outline with heavy dorsal crest. Mandibular teeth usually compressed, bicarinatc and with smooth enamel surfaces." Russell noted that his diagnosis was exclusively based on C. propython and C. liodontus and might not necessarily apply to C. sternbergii (later referred to its own genus, Eonatator) or C. iguanavus.[5]

Teeth and tooth replacement

Mosasaur teeth are of rather uniform morphology (with a few exceptions, such as in Globidens) with a pointed and curved tooth crown that sits on a pedicel composed of bone.[6] The enamel surface is smooth and the crown is subdivided into a lingual and labial surface while the outer surface of the crown is made of enamel and the inner layer is made of dentine.[6] Fossil specimens show evidence of upright vertically positioned developing replacement teeth. Snakes have been thought of as the only squamates with replacement teeth that develop in a horizontal posteriorly inclined position. Snakes deviate from the usual varanoid pattern of tooth replacement, in that their replacement teeth develop in a horizontal inclined position and rotate, however snakes differ from Mosasaurs because they do not possess the resorption pits found in Mosasaurs.[6]

Mosasaurs, including Clidastes, and snakes both share the traits of thecodont tooth implantation, and a recumbent position of replacement teeth. However mosasaurs develop replacement teeth by rotating within the resorption pits that are at the base of functional teeth. This is different from snakes because snakes have recumbent replacement teeth that lay horizontal and rotate into functional position when needed. In mosasaurs like Clidastes, once the functional tooth is lost, a new tooth pedicel develops for the replacement tooth. In the case of mosasaurs though, they differ from the thecodont dentition pattern of archosaur and mammals because mosasaurs show true ankylosis and not a fibrous tooth attachment via periodontal ligament that's usually found in mammals and archosaurs.[7]

The marginal tooth rows in mosasauroids like Clidastes are found on the premaxilla, maxilla and the dentary. On the dorsal surface of the dentary there is an interdental ridge that separates successive teeth labially. These interdental ridges serve to separate succeeding teeth that grow upward between existing teeth.[6]

Occurrences

Clidastes is currently found in marine deposits in the US. In past, however, specimens were referred to this genus from Sweden,[8] Germany,[9] Russia, Mexico,[10] and the Maastrichtian of Jordan.[11] However, Lively (2019) questioned the referral of these remains to Clidastes due to their fragmentary nature and lack of apomorphies placing them in the genus to the exclusion of other mosasaurs.

Discovery

E. D. Cope discovered the first specimens of Clidastes propython in 1869 from the Mooreville Chalk in Lowndes County, Alabama. The remains unearthed were that of a juvenile but are one of the best preserved and most complete mosasaurs collected from the state and is regarded as the generic holotype of Clidastes.[3] In 1918, Charles H. Sternberg and his son found additional remains of Clidastes in Kansas. They were surprised to see that it had humeri and femora with round heads, similar to that of mammals. Due to good preservation of the caudals, Sternberg noted that the chevrons along the vertebrae were ankylosed to the center, which is not observed in other mosasaurs. This synapamorphy was believed to aid in fitting the proximal heads snugly into the basins that hew out from the vertebrae almost locking them in place.

Classification and species

The dental and vertebral morphology of Clidastes is closer to that of Mosasaurus than to any other mosasaur, firmly placing it within the subfamily Mosasaurinae. Besides being different in size, the teeth of Campanian species of Mosasaurus (namely M. missouriensis and M. conodon) differ from those of Clidastes in having a large number of facets that are also more distinct than those in Clidastes. The cervical vertebrae of Clidastes are also different from those in Mosasaurus by being more elongated.[8]

Clidastes is most frequently recovered as one of the most basal mosasaurines, and the most basal hydropedal mosasaurine genus, being more derived than the plesiopedal Dallasaurus but less derived than later genera like Prognathodon or Globidens. The cladogram below is modified from Aaron R. H. Leblanc, Michael W. Caldwell and Nathalie Bardet, 2012:[12]

| Mosasaurinae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

There is only one named species of Clidastes that is valid, C. propython. Clidastes iguanavus Cope, 1868 was the original type species, but the ICZN was petitioned to make C. propython the new type species by virtue of that species being based on diagnostic remains, which it did vis-à-vis Opinion 1750 (1993).[13][14]

Invalid species

There is also an undescribed form from the Mooreville Chalk Formation of Alabama that likely represents a new taxon on its own, informally dubbed "Clidastes moorevillensis", which can be distinguished from both C. propython and C. liodontus based on its dental characteristics.[8] Clidastes liodontus was described from the late Coniacian to early Campanian Smoky Hill Chalk Member of the Niobrara Formation in Kansas.[10] There are also earlier occurrences of the species, dated to the Coniacian, and it might thus be ancestral to the later C. propython.[1] C. liodontus grew to about 3–4 meters in length compared to the 4-5 meter (and on occasion larger) length of C. propython.[1] The type specimen of C. liodontus, consisting of maxillae, a premaxilla and dentaries from the Niobrara Formation of Kansas, was housed at the Bayerische Staatssammlung für Paläontologie and may have been destroyed in the Second World War.[5] Russell (1967)[5] diagnosed the species in general as follows: "Premaxilla “V”-shaped in horizontal cross-section, small rostrum present anterior to premaxillary teeth. Posteroventral portion of root of second premaxillary tooth not exposed on sutural surface with maxilla. Premaxillo-maxillary suture rises posteriorly to position varying from dorsal to fourth to dorsal to sixth maxilIary tooth and parallels longitudinal axis of cranium. Fourteen to fifteen teeth in maxilla. Median dorsal surlace of parietal narrow. Parietal foramen small, close to or distinctly separated from frontal suture. Parietal foramen opens ventrally into brain cavity without broadening into wide excavation. Anterior border of prootic descends beneath prootic incisure without forming shelf. Foramen for cranial nerve VII leaves brain cavity through medial wall of prootic. Infrastapedial process absent on quadrate. Sixteen teeth in dentary." Lively (2019) declared Clidastes liodontus a nomen dubium, while taking note of the nomen nudum status of "moorevillensis", recommending that Clidastes be restricted to C. propython.[15]

Clidastes propython

C. propython is the best studied species of the genus, and was for this reason chosen by the ICZN to replace C. iguanavus as the type species.

C. propython is known from the Campanian of the United States (Alabama, Colorado, Texas, Kansas and South Dakota) and of Sweden.[8][10] The earliest known occurrences of the species are middle Santonian in age and from the Niobrara Formation of Kansas, whilst the latest are Middle to Late Campanian in age, coinciding with a poorly understood middle Campanian intercontinental mosasaur extinction event, which seems to have heavily affected genera such as Clidastes.[8]

Russell (1967)[5] listed the following unambiguous character states for the species: "Premaxilla "V"-shaped in horizontal cross-section, small. rostrum present anterior to premaxillary teeth. Posteroventral portion of root of second premadlary tooth exposed on sutural surface with maxilla. Premaxillo-maxillary suture rises posteriorly in gentle curve to terminate at point above seventh maxillary tooth. Premaxillary suture of maxilla smoothly keeled and paraIIels longitudinal axis of maxilla. Sixteen-18 teeth in maxilla. Median dorsal surface of parietal moderately broad. Parietal foramen smalI, lies close to suture with frontal and opens ventrally into elliptical excavation in parietal, length of which exceeds that of dorsal opening by about five times. Anterior border of prootic forms shelf beneath prootic incisure, then descends abruptly to basisphenoid. Foramen for cranial nerve VII leaves brain cavity through medial wall of prootic. Infrastapedial process present on quadrate. Seventeen to eighteen teeth in dentary.".

Russell (1967)[5] also referred a large number of fragmentary species of Clidastes to C. propython on the basis of that those with good cranial material were morphologically indistinguishable from the type specimen of C. propython. Among these former species now seen as synonyms of C. propython are C. "cineriarum", C. "dispar", C. "velox", C. "wymani", C. "pumilus", C. "tortor", C. "vymanii, C. "stenops", C. "rex", C. "medius" and C. "westi".

Clidastes iguanavus

The Campanian C. iguanavus is the original type species of Clidastes and poorly known in comparison to C. propython and C. liodontus. The type specimen consists of a single vertebra from the anterior thoracic region, YPM 1601, collected in a marl pit near Swedesboro, New Jersey. The vertebra is similar to that of the other species in its general proportions and the strong zygosphene-zygantrum articulation. C. iguanavus can be differentiated in its central articulations, which are kidney-shaped in outline, with a stronger emargination dorsally for the spinal cord, and in the relatively stout proportions of the centrum.[5]

References

- 1 2 3 "Rapid Evolution of Mosasaurs". oceansofkansas.com. Retrieved 2017-09-22.

- ↑ Taylor, L.T.; Minzoni, R.T.; Suarez, C.A.; Gonzalez, L.A.; Martin, L.D.; Lambert, W.J.; Ehret, D.J.; Harrell, T.L. "Oxygen isotopes from the teeth of Cretaceous marine lizards reveal their migration and consumption of freshwater in the Western Interior Seaway, North America". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 573. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2021.110406.

- 1 2 Cope, E.D. 1868. On new species of extinct reptiles. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 20: 181

- ↑ Wright, K. R. (September 23, 1988). The First Record of Clidastes liodontus (Squamata, Mosasauridae) from the Eastern United States. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 8, 3, 343-34

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Russell, Dale. A. (6 November 1967). "Systematics and Morphology of American Mosasaurs" (PDF). Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History (Yale University). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 Olivier, R., & Maureen, K. (December 01, 2005). Tooth Replacement in the Late Cretaceous Mosasaur Clidastes. Journal of Herpetology, 39, 4.)

- ↑ Luan, X., Walker, C., Dangaria, S., Ito, Y., Druzinsky, R., Jarosius, K., Lesot, H Rieppel, O. (January 01, 2009). The mosasaur tooth attachment apparatus as paradigm for the evolution of the gnathostome periodontium. Evolution & Development, 11, 3.)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lindgren, J., & Siverson, M. (January 01, 2004). The first record of the mosasaur Clidastes from Europe and its palaeogeographical implications. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 49, 219-234.

- ↑ Caldwell, M.W., & Diedrich, C.G. 2005. Remains of Clidastes Cope, 1868, an unexpected mosasaur in the upper Campanian of NW Germany. (Igitur.) Igitur.

- 1 2 3 "Fossilworks: Clidastes". fossilworks.org. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ↑ Kaddumi, H.F. (2006). "A new genus and species of gigantic marine turtles (Chelonioidea: Cheloniidae) from the Maastrichtian of the Harrana Fauna–Jordan" (PDF). Vertebrate Paleontology. 3 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-24. Retrieved 2017-09-22.

- ↑ Aaron R. H. Leblanc, Michael W. Caldwell and Nathalie Bardet (2012). "A new mosasaurine from the Maastrichtian (Upper Cretaceous) phosphates of Morocco and its implications for mosasaurine systematics". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (1): 82–104. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.624145.

- ↑ Kiernan, C.R. 1992. Clidastes Cope, 1868 (Reptilia, Sauria):proposed designation of Clidastes propython Cope, 1869 as the type species. Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 49:137-139.

- ↑ ICZN Opinion 1750. 1993. Clidastes Cope, 1868 (Reptilia, Sauria):C. propython Cope, 1869 designated as the type species. Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 50: 297.

- ↑ Joshua R. Lively (2019). "Taxonomy and historical inertia: Clidastes (Squamata: Mosasauridae) as a case study of problematic paleobiological taxonomy". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. in press. doi:10.1080/03115518.2018.1549685.

- Callison, G. (1967). Intracranial mobility in Kansas mosasaurs. Lawrence

- Charles H. Sternberg Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science Vol. 30 (Apr. 18, 1919 - Feb. 19, 1921), pp. 119–120

- Cope, E.D. 1868. On new species of extinct reptiles. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 20: 181

- Dobie, J. L., Daniel, R. W., & Bell, G. L. (June 19, 1986). A Unique Sacroiliac Contact in Mosasaurs (Sauria, Varanoidea, Mosasauridae). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 6, 2, 197–199.

- Kiernan, C. R. (January 1, 2002). Stratigraphic distribution and habitat segregation of mosasaurs in the Upper Cretaceous of western and central Alabama, with an historical review of Alabama mosasaur discoveries. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 22, 1, 91-103.

- Lindgren, J & Schulp, A. (September 1, 2010). New material of Prognathodon (Squamata: Mosasauridae), and the mosasaur assemblage of the Maastrichtian of California, U.S.A. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 30, 5.)

- Wright, K. R. (September 23, 1988). The First Record of Clidastes liodontus (Squamata, Mosasauridae) from the Eastern United States. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 8, 3, 343-345

Notes

- ↑ In mosasaurs, the terms "hydropedal" and "plesiopedal" refers to varying limb conditions and varying degrees of adaptations for marine life. Plesiopedal mosasaurs, such as Dallasaurus or Tethysaurus were primitive and largely coastal, while later hydropedal mosasaurs were streamlined and well-adapted to marine life.

![]() Media related to Clidastes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Clidastes at Wikimedia Commons