| Kaikaifilu Temporal range: Maastrichtian, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Illustration of the left partial humerus who belongs to the holotype specimen | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Superfamily: | †Mosasauroidea |

| Family: | †Mosasauridae |

| Clade: | †Russellosaurina |

| Subfamily: | †Tylosaurinae (?) |

| Genus: | †Kaikaifilu Otero et al. 2017 |

| Species: | †K. hervei |

| Binomial name | |

| †Kaikaifilu hervei Otero et al. 2017 | |

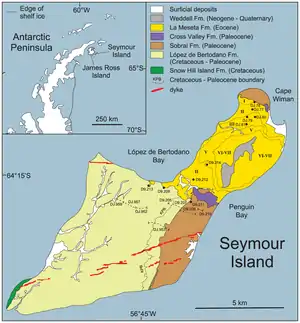

Kaikaifilu is an extinct genus of large mosasaurs that lived during the Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) in what is now northern Antarctica. The only species known, K. hervei, was described in 2017 from an incomplete specimen discovered in the López de Bertodano Formation, in Seymour Island, Antarctic Peninsula. The taxon is named in reference to Coi Coi-Vilu, a reptilian ocean deity of the Mapuche cosmology. Early observations of the holotype classify it as a member of the subfamily Tylosaurinae. However, later observations note that several characteristics show that this attribution is problematic.

Reconstructions of the skull length of the holotype specimen are estimated at 1.1–1.2 m (43–47 in). The maximum size would be approximately 10 m (33 ft) long, making Kaikaifilu the largest mosasaur identified in the Southern Hemisphere, as well as one of the largest tylosaurines known to date, if its attribution to this group remains valid. One of the distinguishing characteristics of this taxon is that it has well-marked heterodont dentition, a trait not found in other tylosaurines.

The fossil record shows that the animal lived in cold waters where temperatures may have dropped below freezing. The López de Bertodano Formation, from which Kaikaifilu is known, shows the presence of other aquatic vertebrates, including fish, plesiosaurs and also other mosasaurs. Dating to the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, Kaikaifilu is one of the last known mosasaurs.

Discovery and naming

The only known specimen of Kaikaifilu hervei, cataloged as SGO.PV.6509, was discovered in January 2011 by the Chilean Paleontological Expedition in the Upper Maastrichtian beds of the López de Bertodano Formation, located on Seymour Island, in the Antarctic Peninsula. Fossil materials include several fragmentary parts of a skull, jawbone, 30 isolated teeth, and a partial left humerus.[1][2][3] Ontogenetic analysis carried out on the fossils shows that they come from an adult individual.[2][3] In 2012, one year after the discovery, a chapter of a scientific work was dedicated to the description of this specimen. The analysis conducted by Rodrigo A. Otero considered it as a mosasaur of the tylosaurine subgroup, but Otero remained uncertain as to whether it was a representative of a previously named taxon or not, leaving this specimen indeterminate.[1] A new anatomical revision published in 2015 confirmed that the remains did indeed belong to a new genus and species,[2] that Otero and his colleagues described and officially named in 2017.[3]

The genus name Kaikaifilu comes from Mapudungun and it is a reference to Coi Coi-Vilu, an aquatic reptilian deity from the Mapuche cosmology. The specific epithet hervei is named in honor of Francisco Hervé, a Chilean geologist who made an important contribution to the knowledge of the geology of Chile and the Antarctic Peninsula.[3][4]

Description

Size

As stored, portions of the holotype skull of Kaikaifilu hervei are around 70 cm (28 in) in length. Based on the skull of Taniwhasaurus antarcticus, a Campanian tylosaurine also known from Antarctica, the total length of Kaikaifilu's skull would be approximately between 1.1–1.2 m (43–47 in). This estimated length places it the largest known mosasaur in the Southern Hemisphere, as well as one of the largest tylosaurines identified to date.[3][4] However, due to uncertainty regarding its attribution to tylosaurines, this latter claim remains subject to debate.[5][6]

Anatomy

Due to the poor preservation of the holotype, few formal descriptions of its anatomy have been made, with researchers noting the state of their preservation. Even some preserved cranial parts are incomplete, thus preventing any definite assessment. The frontals extend forward and between the external nostrils, being in contact with the pineal foramen.[2][3] The latter is slightly concave laterally and has a small keel along its midline. Its suture with the premaxilla and the prefrontal is extended axially and without interdigitation. Behind the maxillary-prefrontal suture, the frontal shows abundant roughness on its dorsal surface. Its suture with the parietal is strongly interdigitated in the midline, becoming like straight flanks laterally and having a posterolateral process of the frontal invading the parietal. Two small ridges appear near the posteromedial margin of the frontal. The parietal extends laterally, being proportionately shorter than wide. The pterygoid appears to be pointed in the rostral direction, which is unusual among mosasaurs. Based on the portions preserved in different fossil blocks, the postorbitofrontal would extend dorsally throughout the orbit. Unlike its contemporary Moanasaurus, Kaikaifilu bears a pre-orbital constriction of the rostrum.[3]

Despite the fact that the mandible is poorly preserved, estimates suggest that more than 15 teeth should be present in dentary bones. Some preserved teeth are interpreted as replacement teeth growing under the functional tooth. Unlike other tylosaurines, an heterodont dentition is seen in Kaikaifilu. Fully developed teeth, although different at various points in the jaw, include some common points. They are conical in shape, have labial and lingual surfaces with smooth ridges extending from base to apex, lack serrated anterior keels, and have a triangular-shaped lateral profile with crowns slightly curved backwards. Four types of teeth are known from the animal: conical teeth of medium size without any wear facets, medium-sized conical teeth with two or three wear facets on their outer and inner faces, very large conical teeth without any wear facets, and small, relatively blunt D-shaped teeth with soft enamel (which may have represent developing teeth).[2][3] The only other mosasaur known to have an heterodont dentition is the mosasaurine Eremiasaurus, also from the late Maastrichian, but from present-day Morocco.[7]

Kaikaifilu's partial humerus is incomplete, only known from the proximal half, but is very robust.[2][3] The articular head has a tall, rectangular and dorso-ventrally broad pre-glenoid process.[3] The pectoral ridge is also prominent and both structures are separated from the glenoid by respective grooves.[2][3]

Classification

As soon as the discovery of the specimen SGO.PV.6509 was officially revealed in 2012, the preliminary descriptions already classified it in the subfamily Tylosaurinae, but could not determine whether the latter was a representative of a new taxon or not.[1] As the fossils are fragmentary and incomplete, almost all the common features of the group are not present on them, making it impossible to directly assign Kaikaifilu within the Tylosaurinae.[3] In addition, some observed characteristics do not seem to correspond to the definition of the group.[5][6] Nevertheless, one of the features present, namely the exclusion of the frontal from the margin of the orbit, is visible in this specimen.[3] However, due to some missing or contradictory traits and the very fragmentary nature of the fossils, subsequent research conducted on tylosaurines cannot include it in their classifications.[5][6]

The first phylogenetic analysis of this specimen was performed in 2015, when the genus was still unnamed. All strict consensus methods place SGO.PV.6509 within the Tylosaurinae, but not always in the same position, the first analysis placing it in a basal position to Taniwhasaurus spp. and the second as a sister taxon to Tylosaurus.[2] In the study officially describing it, all the analyzes carried out also find it as a tylosaurine, with similar results, only the most parsimonious cladogram classifying it as the most basal of the group.[3]

The following cladogram is modified from the phylogenetic analysis conducted by Otero et al. 2017, showing the proposed placement of Kaikaifilu hervei within Tylosaurinae:[3]

| Mosasauroidea |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoecology

Kaikaifilu is known from Upper Maastrichtian deposits of the López de Bertodano Formation, located on Seymour Island, Antarctic Peninsula.[1][2][3] This locality includes layers from the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event, which witnessed the extinction of some of the last remaining mosasaurs like Kaikaifilu. The formation is made up of a 1,100 metres (3,600 ft) thick layer of fine grained silts, clays, and sandstones. Various sections contain fossils of molluscs and crustaceans, suggesting it was part of an ancient sea floor. The depositional environment of López de Bertodano was divided into two main sections; a shallow estuary and a deeper continental shelf, both of which had their own separate invertebrate fauna.[8][9] Located within the polar circle at around 65°S,[10] temperatures at medium to large water depths would have been around 6 °C (43 °F) on average, while sea surface temperatures may have dropped below freezing and sea ice possibly formed at times.[11][12]

The López de Bertodano Formation is already known for the discovery of other genera of mosasaurs, including Moanasaurus, Mosasaurus, Liodon, Plioplatecarpus,[13] and some remains from undetermined tylosaurines. The validity of some of these genera are disputed because they are mainly based on isolated teeth.[3][4][14] Prognathodon and Globidens are also expected to be present based on distribution trends in the world of both genera, although conclusive fossils have yet to be found.[13] Other Antarctic marine reptiles included elasmosaurid plesiosaurs like Aristonectes and another indeterminate elasmosaurid.[15] Plesiosaurs from this formation would have been potential prey for Kaikaifilu.[4] The fish fossils located in the López de Bertodano Formation are dominated by Enchodus and ichthyodectiformes.[16] A large ammonite fauna is known from this site, including the abnormal paperclip-shaped Diplomoceras.[9]

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 Rodrigo A. Otero (2012), "Anifidades morfológicas entre dientes de mosasaurios (Squamata, Mosasauroidea) del Maastrichtiano de Antártica y Chile centra", in Lepe, Mario; Aravena, Juan Carlos; Villa-Martínez, Rodrigo (eds.), Abriendo Ventanas al Pasado. Libro de Resúmenes del III Simposio - Paleontología en Chile (in Spanish), Centro de Estudios del Cuaternario y Antártica del Instituto Antártico Chileno, pp. 146–149, OCLC 1318661175

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Rodrigo A. Otero; David Rubilar-Rogers; Carolina S. Gutstein (2015). Un nuevo mosasaurio (Squamata, Mosasauroidea) del Cretácico Superior de Antártica (in Spanish). XIV Congreso Geológico de Chile.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Rodrigo A. Otero; Sergio Soto-Acuña; David Rubilar-Rogers; Carolina S. Gutstein (2017). "Kaikaifilu hervei gen. et sp. nov., a new large mosasaur (Squamata, Mosasauridae) from the upper Maastrichtian of Antarctica". Cretaceous Research. 70: 209–225. Bibcode:2017CrRes..70..209O. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2016.11.002. S2CID 133320233.

- 1 2 3 4 University of Chile (2016-11-07). "A giant predatory lizard swam in Antarctic seas near the end of the dinosaur age". ScienceDaily.

- 1 2 3 Paulina Jiménez-Huidobro; Michael W. Caldwell (2019). "A New Hypothesis of the Phylogenetic Relationships of the Tylosaurinae (Squamata: Mosasauroidea)". Frontiers in Earth Science. 7: 47. Bibcode:2019FrEaS...7...47J. doi:10.3389/feart.2019.00047. S2CID 85513442.

- 1 2 3 Samuel T. Garvey (2020). A new high-latitude Tylosaurus (Squamata, Mosasauridae) from Canada with unique dentition (MS thesis). University of Cincinnati.

- ↑ Aaron R. H. Leblanc; Michael W. Caldwell; Nathalie Bardet (2012). "A new mosasaurine from the Maastrichtian (Upper Cretaceous) phosphates of Morocco and its implications for mosasaurine systematics". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (1): 82–104. Bibcode:2012JVPal..32...82L. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.624145. JSTOR 41407709. S2CID 130559113.

- ↑ Eduardo B. Olivero (2012). "Sedimentary cycles, ammonite diversity and palaeoenvironmental changes in the Upper Cretaceous Marambio Group, Antarctica". Cretaceous Research. 34: 348–366. Bibcode:2012CrRes..34..348O. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2011.11.015. hdl:11336/5434. ISSN 0195-6671. S2CID 128828799.

- 1 2 James D. Witts; Vanessa C. Bowman; Paul B. Wignall; J. Alistair Crame; Jane E. Francis; Robert J. Newton (2015). "Evolution and extinction of Maastrichtian (Late Cretaceous) cephalopods from the López de Bertodano Formation, Seymour Island, Antarctica" (PDF). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 418: 193–212. Bibcode:2015PPP...418..193W. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2014.11.002. ISSN 0031-0182. S2CID 129879097.

- ↑ David B. Kemp; Stuart A. Robinson; J. Alistair Crame; Jane E. Francis; Jon Ineson; Rowan J. Whittle; Vanessa Bowman; Charlotte O'Brien (2014). "A cool temperate climate on the Antarctic Peninsula through the latest Cretaceous to early Paleogene". Geology. 42 (7): 583–586. Bibcode:2014Geo....42..583K. doi:10.1130/g35512.1. hdl:2164/4380. S2CID 28580206.

- ↑ Vanessa C. Bowman; Jane E. Francis; James B. Riding (2013). "Late Cretaceous winter sea ice in Antarctica?" (PDF). Geology. 41 (12): 1227–1230. Bibcode:2013Geo....41.1227B. doi:10.1130/G34891.1. S2CID 128885087.

- ↑ Thomas S. Tobin; Peter D. Ward; Eric J. Steig; Eduardo B. Olivero; Isaac A. Hilburn; Ross N. Mitchell; Matthew R. Diamond; Timothy D. Raub; Joseph L. Kirschvink (2012). "Extinction patterns, δ18 O trends, and magnetostratigraphy from a southern high-latitude Cretaceous–Paleogene section: Links with Deccan volcanism". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 350–352: 180–188. Bibcode:2012PPP...350..180T. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2012.06.029.

- 1 2 James E. Martin (2006). "Biostratigraphy of the Mosasauridae (Reptilia) from the Cretaceous of Antarctica". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 258 (1): 101–108. Bibcode:2006GSLSP.258..101M. doi:10.1144/gsl.sp.2006.258.01.07. S2CID 128604544.

- ↑ Pablo Gonzalez Ruiz; Marta S. Fernandez; Marianella Talevi; Juan M. Leardi; Marcelo A. Reguero (2019). "A new Plotosaurini mosasaur skull from the upper Maastrichtian of Antarctica. Plotosaurini paleogeographic occurrences". Cretaceous Research. 103 (2019): 104166. Bibcode:2019CrRes.10304166G. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2019.06.012. hdl:11336/125124. S2CID 198418273.

- ↑ José P. O'Gorman; Karen M. Panzeri; Marta S. Fernández; Sergio Santillana; Juan J. Moly; Marcelo Reguero (2018). "A new elasmosaurid from the upper Maastrichtian López de Bertodano Formation: new data on weddellonectian diversity". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 42 (4): 575–586. Bibcode:2018Alch...42..575O. doi:10.1080/03115518.2017.1339233. S2CID 134265841.

- ↑ Alberto L. Cione; Sergio Santillana; Soledad Gouiric-Cavalli; Carolina Acosta Hospitaleche; Javier N. Gelfo; Guillermo M. Lopez; Marcelo Reguero (2018). "Before and after the K/Pg extinction in West Antarctica: New marine fish records from Marambio (Seymour) Island". Cretaceous Research. 85: 250–265. Bibcode:2018CrRes..85..250C. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2018.01.004. hdl:10915/147537. S2CID 133767014.