Climate change is having a range of impacts in the Republic of Ireland. Increasing temperatures are changing weather patterns, with increasing heatwaves, rainfall and storm events.[1] These changes lead to ecosystem on land and in Irish waters, altering the timing of species' life cycles and changing the composition of ecosystems.[2] Climate change is also impacting people through flooding[3] and by increasing the risk of health issues such as skin cancers and disease spread.[4] Climate change is considered to be the single biggest threat to Ireland according to the head of the Defence Forces of Ireland, Mark Mellett.[5]

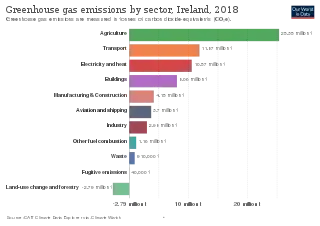

Greenhouse gas emissions

Ireland's greenhouse gas emissions increased between 1990 and 2001 when they peaked at 70.46 Mt carbon dioxide equivalent before decreasing each year up to 2014.[6] In 2015 the emissions increased 4.1%, and in 2016 increased by 3.4% before remaining stable in 2017 and 2018, before decreasing by 4.5% in 2019 from the 2018 levels.[6] Overall, the emissions have increased by 10.1 per cent from 1990 to 2019.

The Central Statistics Office also collate and publish data relating to emissions and the effects as recorded in Ireland.[7]

In 2017, Ireland had the third highest greenhouse gas emissions per capita in the European Union and 51% higher than the EU-28 average of 8.8 tonnes.[8] The world average in 2016 was 4.92 tonnes.[9]

Sources

71.4% of the emissions in 2019 came from energy industries, transport and agriculture, with agriculture the single largest contributor at 35.3%.[10] In Irish agriculture, the two most important greenhouse gases are methane and nitrous oxide.[11] 60% of Irish agricultural emissions come directly from animal agriculture, primarily as a result of methane-producing enteric fermentation from cattle.[11] A further 30% derive from soils fertilised by manures, synthetic fertiliser or animal grazing on pasture.[11][12]

Impacts on the natural environment

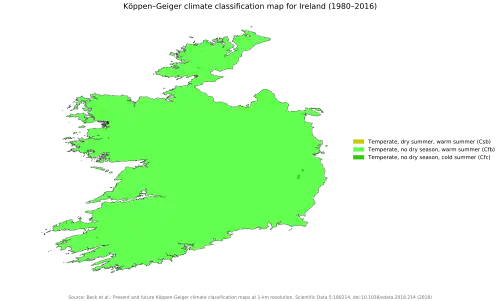

Temperature and weather changes

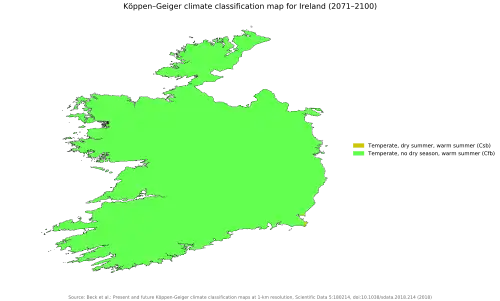

Between 1890 and 2008, the mean temperature recorded in Ireland measured an increase of 0.7 degrees Celsius, with an increase of 0.4 degrees Celsius between 1980 and 2008.[13] Other indicators of a warming climate identified by the Environmental Protection Agency are ten of the warmest recorded years occurring since 1990, a decrease in the number of days with frost and a shorter season in which frost occurs, and increased annual rainfall in the north and west of the country. An increase in the active growing season has been recorded, as well as an increase in animals arriving in Ireland and its surrounding waters which are adapted to warmer conditions.[14]

A 2020 study from the Irish Centre for High-End Computing indicated that Ireland's climate is likely to change drastically by 2050.[2] Annual average temperatures could climb to 1.6 °C above pre-industrial levels under RCP8.5, with the east of Ireland seeing the highest increase, resulting in a "direct impact" on public health and mortality.[2][15] The study also predicted the number of frost days to decrease between 68 and 78 per cent, summer precipitation to decrease by up to 17%.[2]

In June 2023, there was a Category 4 (extreme) marine heatwave in Irish waters, with some regions experiencing a Category 5 (beyond extreme) increase in temperatures.[16] During this heatwave sea surface temperatures reached their highest ever recorded in Irish waters.[17]

Ecosystems

Temperature changes risk disrupting or changing the timing of the life cycle of plant and animal species across the country.[2] For example, the timing of leaf unfolding in Irish beech trees has become steadily earlier since the 1970s.[18] Changes to the timing of life cycle events (phenology) can result in temporal mismatches between species, as not all species and life history events are equally responsive to temperature.[19] Such changes may result in disruption of previously synchronised ecosystem function, resulting to changes in species composition and functioning of Irish ecosystems.[20]

Ocean acidification has been recorded in the waters off at Ireland since records began in 1990 by the Marine Institute.[21] This is caused by the uptake of atmospheric carbon dioxide into the ocean. In addition to acidification, Irish waters are becoming warmer and less salty, causing harm to marine life.[22] Harmful algae are becoming more abundant in Irish waters, not just in warmer months, potentially harming ocean creatures such as shellfish.[22]

Impacts on people

Sea level rise and flooding

One of the greatest threats is to coastal and low lying regions from sea level rise, alongside increased rainfall and storm events. 40% of the population live within 5 km of the coast,[23] and 70,000 Irish addresses are at risk of coastal flooding by 2050.[3] Sea levels have risen around by 40 cm around Cork since 1842, approximate 50% greater than previously expected.[24] The rate of sea level rise around Dublin is approximately twice the global rate.[25]

Storm surges also have an increased risk of occurring with rising temperature, with climatologists predicting that Ireland is overdue a 3m storm surge.[3] In addition to coastal flooding, flooding due to increased groundwater levels is also a risk.[26]

Drought

An increase in water shortages are expected due to periods of drought, and a decrease in water quality.[14]

Health impacts

Adverse health issues relating to climate change have also been identified by the Irish Health Service Executive, including increased risk of skin cancers, waterbourne, foodborne and respiratory diseases.[4]

Mitigation and adaptation

Policies and regulation

The previous governing policy on mitigation, the 2017 National Mitigation Plan, was quashed by the Irish Supreme Court in August 2020. The Court ruled that the plan was contrary to the 2015 Climate Action and Low Carbon Development Act.[27]

Agencies, such as the Geological Survey of Ireland (GSI), have formulated a number of projects aimed at providing alternatives to current energy sources and the movement away from the contributing factors of climate change. These include the GSI's research into geothermal technologies and carbon sequestration.[28]

Climate change Bill 2021

On 23 July, the Climate Action and Low Carbon Development (Amendment) Bill 2021 was signed into law by the President. The bill creates a legally binding path to net zero emissions by 2050.[29] Five-year carbon budgets produced by the Climate Change Advisory Council will dictate the path to carbon neutrality, with the aim of the first two budgets creating a 51% reduction by 2030.[30] The five-year budgets will not be legally binding.[31]

Despite being touted as "ambitious" by the Irish Government, the bill came under heavy criticism from Irish environmentalists and scientists.[32] Amendments passed by the Seanad on 9 July allow the Government, rather than the Climate Change Advisory Committee to determine how greenhouse gas emissions are calculated and taken into account.[32] Climate scientist and IPCC author John Sweeney argued that these amendments "depart from the scientifically established methodology and give discretion to the Government to decide what to measure, how to measure it, and what the removals will be and how they are counted".[32]

See also

References

- ↑ Taggart, Emma (24 July 2021). "'Irish temperature records will be broken in the coming years because we're in a climate crisis'". TheJournal.ie. The Journal. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Ireland's climate likely to drastically change by 2050". Green News Ireland. 18 September 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 O'Sullivan, Kevin (21 May 2020). "Over 70,000 Irish addresses at risk of coastal flooding by 2050". The Irish Times. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- 1 2 "Climate change and health". HSE.ie. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ↑ O'Connor, Niall. "Head of Defence Forces says climate change is single biggest threat to Ireland". TheJournal.ie. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- 1 2 "Current trends climate". www.epa.ie. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ↑ "Environmental Indicators Ireland 2018". Central Statistics Office. August 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ↑ "Greenhouse Gases and Climate Change - CSO - Central Statistics Office". www.cso.ie. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ↑ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max. "Per capita greenhouse gas emissions". Our World in Data. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ↑ "Climate". Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- 1 2 3 "2020 - Agricultural Emissions - greenhouse gases and ammonia - Teagasc | Agriculture and Food Development Authority". www.teagasc.ie. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ↑ Thompson, Sylvia (17 June 2021). "Can Irish farmers reduce greenhouse gas emissions?". The Irish Times. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ↑ "Effects in Ireland". www.gsi.ie. Geological Survey of Ireland. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- 1 2 "What Impact will climate change have for Ireland?". Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ↑ Flanagan, Jason; Nolan, Paul. Research 339: High-resolution Climate Projections for Ireland – A Multi-model Ensemble Approach. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-84095-934-5. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ↑ "Record-breaking North Atlantic Ocean temperatures contribute to extreme marine heatwaves | Copernicus". climate.copernicus.eu. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ↑ "Marine Heat Wave 2023 – A Warning for the Future - Met Éireann - The Irish Meteorological Service". www.met.ie. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ↑ Donnelly, Alison; Salamin, Nicolas; Jones, Mike B. (2006). "Changes in Tree Phenology: An Indicator of Spring Warming in Ireland?". Biology and Environment: Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. 106B (1): 49–56. doi:10.1353/bae.2006.0014. ISSN 0791-7945. JSTOR 20728577. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ↑ Ockendon, Nancy; Baker, David J.; Carr, Jamie A. (July 2014). "Mechanisms underpinning climatic impacts on natural populations: altered species interactions are more important than direct effects". Global Change Biology. 20 (7): 2221–2229. Bibcode:2014GCBio..20.2221O. doi:10.1111/gcb.12559. PMID 24677405. S2CID 39877152.

- ↑ "Ireland's Biodiversity Sectoral Climate Change Adaptation Plan" (PDF). www.npws.ie. National Parks & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ↑ "Nutrients and Ocean Acidification (OA)". Marine Institute. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- 1 2 Hoare, Pádraig (7 March 2021). "Climate change already impacting Irish waters". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ↑ "Population Distribution - CSO - Central Statistics Office". www.cso.ie. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- ↑ Pugh, David T.; Bridge, Edmund; Edwards, Robin; Hogarth, Peter; Westbrook, Guy; Woodworth, Philip L.; McCarthy, Gerard D. (11 November 2021). "Mean sea level and tidal change in Ireland since 1842: a case study of Cork". Ocean Science. 17 (6): 1623–1637. Bibcode:2021OcSci..17.1623P. doi:10.5194/os-17-1623-2021. ISSN 1812-0784.

- ↑ "Why sea levels are rising higher than expected in Dublin and Cork". 28 April 2022. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- ↑ "Climate Action at Geological Survey Ireland". www.gsi.ie. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ↑ "Climate change: 'Huge' implications to Irish climate case across Europe". BBC News. 1 August 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ↑ "Climate Research at Geological Survey Ireland". www.gsi.ie. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ↑ "Ireland's ambitious Climate Act signed into law". www.gov.ie. 23 July 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ↑ McDermott, Stephen. "Carbon neutral by 2050: Ireland's green targets to be legally binding for the first time". TheJournal.ie. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ↑ Crosson, Kayle (26 March 2021). "A deep dive: the revised Climate Bill". Green News Ireland. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Recent amendments have "gutted" Climate Bill". Green News Ireland. 12 July 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.