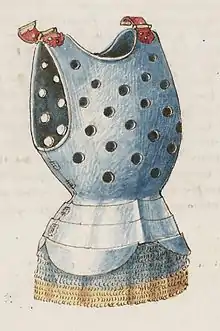

A coat of plates is a form of segmented torso armour consisting of overlapping metal plates riveted inside a cloth or leather garment. The coat of plates is considered part of the era of transitional armour and was normally worn as part of a full knightly harness. The coat saw its introduction in Europe among the warring elite in the 1180s or 1220s and was well established by the 1250s.[1] It was in very common usage by the 1290s.[2] By the 1350s it was universal among infantry militias as well.[1] After about 1340, the plates covering the chest were combined to form an early breastplate, replacing the coat of plates.[3] After 1370, the breastplate covered the entire torso.[3] Different forms of the coat of plates, known as the brigandine and jack of plates, remained in use until the late 16th century.[2]

Construction

The plates number anywhere from eight or ten to the hundreds depending on their size. The plates overlap, usually enough to guarantee full coverage even when moving around and fighting. The coat of plates is similar to several other armours such as lamellar, scale and brigandine. Unlike scale armour which has plates on the outside or splint armour in which plates can be inside or outside, a coat of plates has the plates on the inside of the foundation garment. It is generally distinguished from a brigandine by having larger plates, though there may be no distinction in some examples.

In his 2013 PhD thesis, Mathias Goll suggests that this kind of armour made from several segments held together via leather or fabric only should be described as “segmented-armour”, in this case in the subtype "torso-front-and-back-segmented".[4]

Goll suggests a later dating of the saint Maurice statue in Magdeburg, possibly moving its production from the second half of the 13th century to the first half of the 14th century. He interprets the backplates of his coat of arms as vertically arranged lames held in place beneath leather or fabric by horizontal rows of rivets, like on some of the Visby plates.[5]

Visby armour

One of the best resources about coats of plates are the mass graves from the Battle of Visby. The Visby coats of plates display between 8 and some 600 separate plates fastened to their backings.[6] The mass grave from a battle in 1361 has yielded a tremendous number of intact armour finds including 24 distinct patterns of coat of plates style armour. Many of these were older styles similar to the armoured surcoat discussed below.

Development

The early coat of plates is often seen with trailing cloth in front and back, such as seen on the 1250 St. Maurice coat.[7] These has been described as metal plates riveted to the inside of a surcoat. There is debate regarding whether the plates inside the armoured surcoat overlapped, but the armour is otherwise similar. Quantitatively speaking, however, most of the known evidence for coat of plates and brigandines dated from 14th and 15th centuries actually displays arrangements of overlapping plates; and although there are exceptions to this rule, they are not many.

Presumably, the development and the later popularization of this type of harness is directly linked to the knightly needs for better protection against cavalry lances, since the former protection of mail and aketon made the horseman vulnerable only to such strikes. In Mike Loades' military documentary called Weapons that Made Britain: Armor, the older set of mail harness and aketon proved itself unable to stop lance strikes at horseback charges. The addition of an authentic reproduction of coat of plates, however, provided sufficient protection against all the lance strikes, even the most powerful of them could not penetrate through the combination of padding, mail and plates, proving its effectiveness as the new cavalry protection.

The earliest use of iron plate reinforcements is recorded by Guillaume le Breton.[8] In his Phillippidos, prince Richard - later King Richard I of England - is described wearing a ferro fabricata patena at a jousting tournament in 1188. Such iron breastplate, like later references of early developments of such harness, was described being worn under the hauberk, thus not being visible when all the armor was properly worn. The evidence that such new harness is first mentioned at jousting reinforces the assumption that such developments were designed to protect against lance strikes.

Iron plate reinforcements would be recorded again in Heinrich von dem Türlin's Diu Crône, from 1220's; the gehôrte vür die brust ein blat is mentioned after the gambeson, hauberk and coif, but before the surcoat, thus still not being entirely visible. Later sources usually describe these new iron reinforcements being worn under traditional armour in this way, which explains why this sort of armour seldom appears in illustrations and statuary before the late 13th century.

By mid-13th century, artistic evidence shows similar plate pattern to that of St. Maurice's Effigy in a German manuscript.[9] The fact that German men-at-arms often are described with this armor in art or military records under foreign lands might suggest they were behind their popularization in Europe by that time. The coat of plates worn by German knights at the battles of Benevento in 1266 and Tagliacozzo in 1268 rendered them nearly invincible against French sword blows, until the French realized the German armpits were poorly protected.[10] Contemporary to this, Scandinavian sources from mid-to-late 13th century also make reference to it: in the Konungs skuggsjá, from around 1250, it is called a Briost Bjorg and specifies that is should cover the area between the nipples and the belt. The later Hirdskraa of the 1270s calls it a plata, informing that it should be worn beneath the hauberk, permitting it only to the highest ranks of Scandinavian military, from skutilsvein (knight) and up. In Barcelona, for instance, there was a local production of coats-of-plates — then called "cuirasses" − beginning in 1257; King James II of Aragon ordered such cuirasses to be made for him and his sons in 1308, which were covered in samite fabric of different colors.[11]

In the transitional period segmented armour like the coat of plates was replaced by larger, better shaped and fitted plates. Mathias Goll stresses that while plate armour was more effective, the segmented armour could be "lighter and more flexible while it left less 'dangerous' chinks". The segmented armour also put fewer demands on the craftsman, requiring fewer tools and less skill, thus being prominently cheaper. As a consequence, the "older" types could remain in production alongside more "modern" developments. In addition to protection and wearer comfort, this armor was also chosen for fashion.[12] In 1295, the coat of plates was worn along with mail by nearly all troops in an army gathered by King Philip IV of France.[2] In that same year, a Lombard merchant brought to Bruges the huge amount of 5,067 coats-of-plates, alongside other equipment.[13] The armor was so popular that in 1316 the captured harnesses of the Welsh noble Llywelyn Bren included a "buckram armor".[14] By the second half of the 14th century, the coat of plates became affordable enough to be worn by soldiers of lesser status, like the Gotland's militiamen or the urban militia of Paris.

After being replaced by plate armour amongst the elite, similar garments could still be found in the 15th century, as the brigandine. The Portuguese 'Regimento dos Coudéis' from 1418 states that the most basic body armor accessible for a non-gentle soldier was, indeed, such armor. [15] Another similar but later garment was the coat or Jack of plate which remained in use until the end of the 16th century.

See also

Citations

- 1 2 Smith 2010, p. 69.

- 1 2 3 Williams 2003, p. 54.

- 1 2 Smith 2010, p. 70.

- ↑ Goll, Matthias 2013, Iron Documents Interdisciplinary studies on the technology of late medieval European plate armour production between 1350 and 1500, PhD Heidelberg, p. 42.

- ↑ Goll 2013: 69.

- ↑ Thordeman, Armour from the Battle of Wisby, 1361, 211

- ↑ Counts, David, "Examination of St. Maurice Coat of Plates", Aradour, visited Mars 22nd 2016

- ↑ Philippidos, Book III, line 497.

- ↑ Cambridge MS Mm.5.31, fo.139r, Bremen, 1249-1250

- ↑ Williams 2003, p. 53.

- ↑ Williams 2003, p. 815.

- ↑ Goll 2013: pp. 53.

- ↑ Nicolle, David, 1999, In 1295 a Lombard merchant brought no fewer than 1,885 crossbows, 666,258 quarreli, 6,309 small shields, 2,853 light helmets, 4,511 quilted coats, 751 pairs of gauntlets, 1,374 gorgiera neck protectors and brassards, 5,067 coats-of-plates, 13,495 lances or lanceheads, 1,989 axes and 14,599 swords and couteaux daggers to Brugge, p. 53.

- ↑ Heath, Ian 1989, the confiscated armor of the rebel Llywelyn Bren (of the royal house of Senghenydd in Glamorgan) is recorded to have comprised an aketon, a gambeson, 3 haubergeons, an iron breastplate, a buckram armor (doubtless a coat-of-plates), an iron helmet, 2 pairs of maunc' (vambraces), a shield and a pair of gauntlets. Though this harness is somewhat more comprehensive than that generically in use at the end of the 13th century, the significant point is that would have made Llywelyn Bren undistinguishable from his English adversaries., p. 93.

- ↑ Monteiro, João Gouveia, 1998, To the aquantiados on 32 marcs of silver, it was just demanded horse, while those of 24 marcs and up had to had crossbows spanned with goat's foot lever, a hundread bolts and yet, as defensive arms, coat-of-plates, bascinet with camail or bascinet of baveira, p. 49.

References

- Smith, R. (2010). Rogers, Clifford J. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology: Volume I. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195334036.

- Edge, David; John Miles Paddock (1993) [1988]. Arms & Armor of the Medieval Knight (Crescent Books reprint ed.). New York: Crescent Books. ISBN 0-517-10319-2.

- Thordeman, Bengt (2001) [1939]. Armour from the Battle of Wisby, 1361 (The Chivalry Bookshelf reprint ed.). The Chivalry Bookshelf. ISBN 1-891448-05-6.

- Counts, David. "Examination of St. Maurice Coat of Plates", The Arador Armour Library, retrieved 3/22/07

- Edge and Paddock. Arms and Armour of the Medieval Knight. Saturn Books, London, 1996.

- Heath, Ian. Armies of Feudal Europe 1066 - 1300. Wargames Research Group Publication, Sussex, 1989.

- Williams, Alan (2003). The Knight and the Blast Furnace: A History of the Metallurgy of Armour in the Middle Ages & the Early Modern Period. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004124981.

- Nicolle, David (1999). Italian Militiamen 1260 - 1392. Osprey Publishing.

- Monteiro, João Gouveia (1998). A Guerra em Portugal nos finais da Idade Média. Notícias Editorial.