| Cockatoo Island Industrial Conservation Area | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Cockatoo Island, Sydney Harbour, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°50′52″S 151°10′20″E / 33.8477°S 151.1721°E |

| Official name | Cockatoo Island Industrial Conservation Area |

| Type | Listed place (Historic) |

| Designated | 22 June 2004 |

| Reference no. | 105262 |

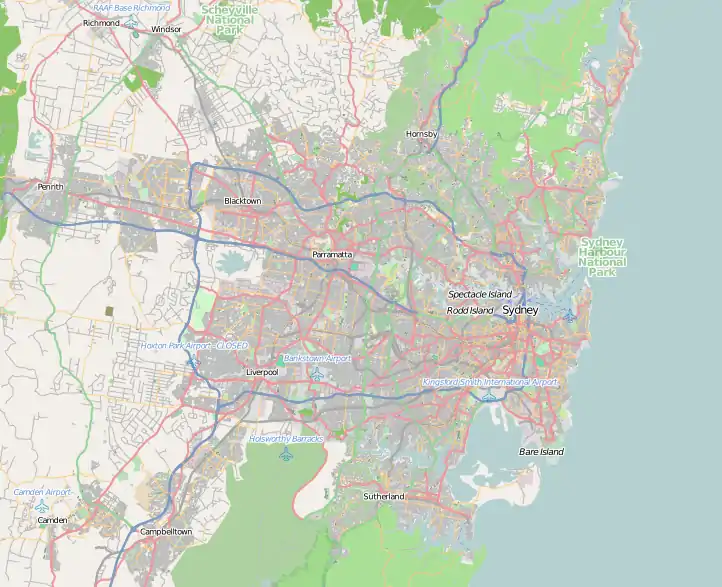

Location of Cockatoo Island Industrial Conservation Area in Sydney | |

Convict Barracks Military Guard Room Mess Hall Sutherland Dock Fitzroy Dock Biloela House Underground Grain Stores Power House | |

Cockatoo Island Industrial Conservation Area is a heritage-listed protected area relating to the former Cockatoo Island Dockyard at Cockatoo Island, Sydney Harbour, New South Wales, Australia. It was added to the Australian Commonwealth Heritage List on 22 June 2004.[1]

History

Cockatoo Island is the largest island in Sydney Harbour. It is not known who first called it Cockatoo Island, though it was known as such long before it was called Biloela. This name was given to the island in 1870 by the Reverend William Ridley, a student of an Aboriginal language, in response to a request from the Governor for a suitable name. The island has been subject to five major administrative/occupation phases.[1]

Prison Dockyard 1839-64

The expansion of settlement 1810-20 under Governor Macquarie led to the construction of places of confinement including Norfolk Island and Macquarie Harbour. Assigned convicts were left under the control of landowners but convicts in government service and secondary offenders in penal settlements were housed in barracks as soon as these could be constructed. In time the settlements on Norfolk Island and in Tasmania were defeated by isolation and the inability of Sydney and Hobart based administrators to exercise adequate control. In 1839 Governor Gipps advised the Secretary of State for the Colonies that he was forming an establishment on Cockatoo Island for Imperial prisoners withdrawn from Norfolk Island. Unlike contemporary New South Wales (NSW) penal establishments which were executed under contract, the work on Cockatoo Island was carried out by the prisoners. Expenses were met from Imperial, not Colonial, funds emphasising the role of the Imperial Government in the establishment of Cockatoo Island. The buildings were constructed to the design of the commanding Royal Engineer, George Barney, responsible for convict and military buildings in NSW. Twelve grain silos were also cut out of the rock in 1839 to store grain, following Gipps' order that the government would make provision for the storage of 10,000 bushels on the island within two years. The year 1839 also saw the expansion of the island's convict gaol with the construction of the barracks; U-shaped in plan, the barracks held accommodation for 344 convicts. As transportation ceased in 1840 the prison was used to house an increasing number of colonially sentenced convicts. As the island was surrounded by deep water it was ideal for maritime activities as a British outpost at a time of increasing rivalry between European nations and the United States of America in the Pacific Ocean. In 1846 Governor Gipps reported to the British Government that convicts would be employed in clearing and preparing the island for the construction of a dry dock. Approved in 1847 the colonial government built Fitzroy Dock between 1847-57 with convict labour. The first ship, HM Surveying Brig Herald, docked in 1858. Gother Kerr Mann, one of Australia's foremost nineteenth century engineers, was responsible for the design and construction of Fitzroy Dock, the first begun in the southern hemisphere and contemporary with Mort's Dock at Woolwich. Captain Gother Mann was Engineer in Chief at Cockatoo Island from 1847 and later became Superintendent of Convicts. During this time additions were made to the gaol including an ornate mess hall and houses for prison officials including Biloela House for the prison governors. This period was also one of brutality against any unrest from the prisoners leading to a Select Committee of Inquiry chaired by Henry Parkes in 1861. The brutalising conditions of the Island were admitted but no discernible improvements occurred. Up to 500 prisoners were held there but the usual number was about 250. Officers' accommodation was erected in the 1840s-50s including superintendents quarters, clerk of petty sessions, military officers quarters and quarters for the free overseer.[1]

NSW Department of Public Works 1864-1913

During this period the administration of the dockyard and prison split. The land above the escarpment remained in institutional use but, as the docks expanded, the foreshores became dedicated to dockyard use. During the latter part of the nineteenth century Sydney's population increased rapidly producing a poorly educated, dysfunctional, community. Punishment, reform and education became key concerns. Cockatoo Island is associated with this period through the training ship Vernon and the establishment of the Girls Institution and Reformatory from 1871-88. In 1871 the training ship Vernon for boys, an initiative of Henry Parkes, was anchored at the north-east corner of the island with recreation grounds and swimming baths by 1896. Although the young prisoners were kept separate from the dock they worked there on ship building and repairs. From 1861 dock development had occurred with the first stone workshop buildings for metal working, foundry and general activities, drawing and administrative offices. In 1868 Fitzroy Dock was reported to be the third most important dry dock in the country after Mort's Woolwich dock and the Australasian Steam Navigation Company works in Pyrmont. By 1870 a new dock was recommended at Cockatoo Island by Captain Gother Kerr Mann. While this was being debated the male prisoners were transferred to Darlinghurst gaol from the island in 1871. During the 1870s the Underground Grain Silos were pressed into service for water storage. In 1869 the Executive Council had approved the transfer of prisoners from Cockatoo to Darlinghurst; the prison buildings subsequently became an Industrial School for Girls and a Reformatory in 1871. However, overcrowding elsewhere forced the return of male prisoners and the barracks were divided between prisoners of both sexes. The new dock, approved in 1882, was longer than any existing in the world. This dock, the Sutherland Dock, built by private contractors and free labour, eventually cost £268,000 and was completed in 1890. The tender was awarded to twenty-three year old Australian engineer Lewis Samuel. New workshops were also built with wharfage for repair work. However, during the 1880s prison accommodation continued to deteriorate and the number of prisoners declined to about 100 each, male and female. In 1888 the girls departed and the establishment was again proclaimed a prison. Further additions included a fumigation building, surgeon's consulting rooms and isolation cells were added in 1897 with stone quarried on site. Although the prison was condemned in 1899 by the Public Works Committee it remained in operation. Electricity was installed in 1901, the birth year of the new independent nation, the Federation of Australia. As British control ceased in 1901 the NSW government took over with further building of workshops in corrugated iron on steel frames forming additions to the original stone workshops. The dockyards expanded rapidly. Major new workshops were provided, now largely in brick, along the eastern shore with docking wharves and included an erecting shop, foundry, blacksmith and shipwright shop. In 1903 a Royal Commission was established to look at all aspects of the working of the Government docks and workshops. In 1908 a steel foundry was established on the Island followed by a range of new workshops. By 1905 parts of the men's prison quarters collapsed so that in 1906 they were transferred to shore for the last time and relocated at Long Bay Gaol. The female prison division was similarly closed in 1909; NSS Sobraon, the school ship, was given to the Royal Australian Navy in 1911 and became HMAS Tingira.[1][2]

Commonwealth Dockyard 1913-33

In 1911 the Royal Australian Navy was established and in 1913 the Australian Government bought the island from NSW for £870,000 pounds. Despite the building expansion from 1900 much of the dock and workshops equipment was in poor shape and major expansion and upgrading of equipment was increased. Development occurred on the escarpment above the dockyard. By 1912 a lift had been constructed up the escarpment with most of the structures in the centre of the island demolished and replaced by more efficient structures. The prison buildings were converted into drawing offices and new boiler and turbine shops added. The old power house, containing a steam driven dock pump and consisting of a brick building with columns and arches attached to the facade, was demolished. The new larger power house and chimney built in 1918, which still stands, provided for steam turbine electric generating equipment, electrically driven air compressors, dock-dewatering pumps and hydraulic pumps. The Australian Government had ordered several naval vessels in 1912, including the cruisers HMAS Brisbane and HMAS Adelaide each of 5,600 tonnes and 25,000 shaft horse power (18,650kw) and several destroyers. One of these, HMAS Heron, was handed over in February 1916 to become the first steel warship to be built in Australia. No 1 slipway was lengthened whilst the Brisbane was being built for its launching in 1915 and the floating crane Titan was assembled from British-made sections. Little further development occurred between the wars. As naval activity decreased, commercial shipbuilding grew until the Depression when all activity declined. Under Navy control until 1921 it was then placed under a Board of Control responsible to the Prime Minister's Department soon superseded by the Australian Commonwealth Shipping Board. During the 1920s, in addition to industrial structures, three pairs of houses were erected on the island. In 1928 the Sutherland Dock was enlarged and a decision made to lease the dockyard to private enterprise.[1]

Cockatoo Docks and Engineering 1933-48

In 1933 the island was leased to Cockatoo Dock and Engineering Company Ltd (later Pty Ltd). With the outbreak of World War Two the island became the major ship repair facility in the Western Pacific, following the loss of Singapore. Major repairs and fitting out were undertaken at the docks including work on troop carriers, the RMS Queen Mary and RMS Queen Elizabeth, RMS Aquitania and RMS Mauretania and major vessels of the Royal Australian Navy and United States Navy. Two tunnels were constructed during the war under the plateau to improve material movement on the island. New buildings were erected throughout this period. The war years, 1939-46, saw the reconstruction of roads and the construction of a new road giving access to the upper part of the island. Six wharves, once covered by five ton and fifteen ton travelling cranes, were available for berthing ships for fitting out or refitting. The maximum depth of water alongside wharves was about 26ft. The Titan, a 150 ton floating crane commissioned in 1917, was another important facility. During the war period it operated almost continuously. It was used for commercial as well as naval work and dealt with numerous lifts of heavy and important equipment in the port. The workshops included the engineering shop, the electrical section, the tool section and the sheet metal section and a well equipped standards room and meteorology section. The yard's own quality control section operated above and beyond the normal navy overseeing staff. In 1947 Vickers UK purchased Cockatoo Dock and Engineering Pty Ltd and established Vickers Cockatoo Docks and Engineering.[1]

Vickers Cockatoo 1948-1992

In 1950 the Australian Commonwealth Shipping Board ceased to function and was replaced by the Cockatoo Island Lease Supervising Committee. The top level of the island had by now drawing offices for each of the hull, engineering and electrical sections, the estimating, planning and costing offices and residences for several of the executive staff of the yard. More recently, two large concrete water towers were constructed on the plateau and several brick and concrete buildings were added to the southern and eastern shores. In December 1992 the original lease expired; the island is still owned by the Commonwealth. Between 1992-93 some forty buildings were demolished. Several other structures are no longer extant.[1]

Description

Cockatoo Island Industrial Conservation Area is about 18 hectares (44 acres) in Sydney Harbour, between Birchgrove Point and Woolwich Point, comprising the whole of the Island to low water.[1]

Cockatoo Island contains a wide variety of extant buildings and structures which contribute to the cultural landscape. The vistas to and from the island play an important role in the character of the setting. The island's present landform has been developed through quarrying and landfill with natural elements limited in extent and profile. The cultural landscape is articulated by man-made cliffs, stone walls and steps, docks, cranes, slipways and simple built forms. A number of areas or precincts have been identified within the cultural landscape.[3] These include the area of the Colonial Prison, the Docks precinct, the timber boatbuilding and workshops precinct, the docks workshops precinct, the powerhouse and slipways precinct, the technical offices and workshops precinct and the residential precinct. The building types and architectural styles generally reflect the administrative/occupation period in which they were constructed.[1]

1839-1864

Construction generally occurred on the upper parts of the Island and included the prisoner's barracks 1839-42, mess hall 1847-51 and the military guard house of 1842 in the Colonial Georgian style and the two storey military officers quarters 1845-57 and the free overseers quarters 1850-57 in a restrained Victorian Georgian style all in the local sandstone. To the east residential buildings include the superintendent's quarters (Biloela House) c 1841 and the clerk of petty sessions residence c 1845-50 and a number of smaller structures characterised by their simple plans, stone walls and hipped or gabled roofs. Among the latter is the former iron and steel foundry erected c 1856 as a sandstone machine shop. Other items include the in-ground water tanks and grain silos the (former) engine house and workshop and the rock cut Fitzroy Dock or No 2 Dock; length 474ft maximum beam of vessel Fitzroy Dock, which could be docked 48ft maximum draft 18ft (at high water at ordinary spring tides). The dock retains its entrance caisson in place. Associated with the construction of the Fitzroy Dock is the engineers and blacksmith's shop of c 1853 in the Victorian Georgian style. This building is one of the earliest surviving industrial structures on the island and a vital feature of the nineteenth century industrial environment of Sydney. The associated two storey boilers, pumping engines and offices building was erected c 1845-57 in the Victorian Georgian style; the primary building housed the Fitzroy Dock pumping station from 1853.[1]

1864-1913

Less built development occurred during this period with new uses accommodated through adaptation and alteration. Additions were made to the dockyards and several new warehouses built. These include a Federation style brick and stone building, as well as a combination of steel framed and clad buildings on the east, south and west sides of the Fitzroy Dock. The latter include the mould loft, the shipwrights shed, the pattern storage buildings. The powerhouse built with Sutherland Dock at the western end of the Island was replaced in 1918 by the present Federation Warehouse style power house on the docks. Sutherland Dock, or No 1 Dock, completed 1882-90 has a length of 690ft, a breadth of 88ft and a depth over the sill of 32ft. At high water of ordinary spring tides, the maximum breadth at which a ship could be docked, was 85ft. The largest ship accommodated was the QSMV Dominion Monarch, 26,500 tons, 620ft x 84ft 10 inches. The heavy machine shop of 1896 abuts the engineers and blacksmith's shop of 1853. Other warehouse type structures which survive from this period include the boiler house of 1908, the engine house of 1909 and the coppersmith's shop.[1]

1913-1947

Substantial built development took place during this period related to the expansion of the dockyards. Several larger scale industrial warehouse buildings were erected in the centre of the island on the site of the former Biloela Female Gaol. These buildings are primarily steel framed with corrugated galvanised iron cladding. Extant buildings of this type include the estimating and drawing offices 1915-18 and the electrical shop 1915-16. Other buildings were constructed in the dockyards area; these appear to have been subsequently demolished with the exception of the Federation styled timber vernacular administration buildings to the south. The powerhouse of 1918 in the Federation Warehouse style is constructed of load bearing brickwork below a steeply pitched gabled roof. The powerhouse chimney remains in place. Residential buildings in the western part of the higher ground include primarily Federation style semi-detached structures executed characteristically in red brick with tiled roofs. These semis have been extended with fibro additions. A two storey semi 1913-16 to the north is more impressive in its architectural expression and features sunhoods, decorative eaves and balustrades. During the Cockatoo Docks and Engineering Phase (1933-48) numerous warehouses were built which dominate the lower levels of the island. These are predominantly steel framed and clad with corrugated iron sheeting. Other structures are related to the importance of local river traffic on the surrounding waterways; the Parramatta Wharf turnstile shelter of 1945 is one of these. The muster station of 1945 is a reminder of the post war operation of the dockyards. Other structures, including air raid shelters and administration buildings, are evidence of the importance and operation of the island during the hostilities of World War Two.[1]

1948-1992

Numerous warehouses were built during this phase. Many are steel framed with corrugated iron sheeting cladding. A group of red brick warehouses with curved roofscapes were constructed primarily after World War Two. A group of international style buildings at the south-eastern corner of the dockyards forms a distinct group. Among the latter is the former weapons workshop of 1971.[1]

In addition to the standing buildings described above the island contains numerous items of remnant equipment. Significant items include two Belliss and Morcom steam engines, lathes, planing equipment, hydraulic presses, plate bending machinery, boring machines, rivet presses, threading machinery, plate rolls, steam hammers and cutting equipment. The only building which retains its equipment intact is the powerhouse; equipment includes the dewatering system, the air compressors, the hydraulic pumps and the mercury rectifier bank used to convert AC to DC. The dockyard areas include a steam-driven rail-mounted jib crane of mixed parentage (possibly 1870), electric travelling portal jib cranes and long jib cantilever cranes of the 1920s, electric travelling jib cranes of the 1940s, fixed tower cranes of the 1960s and electric portal jib cranes of the 1970s. The waterfront areas also accommodate wharves, slipways and shipbuilding berths. Among the latter are shipbuilding berths No 1 and No 2, slipways 3 and 4 and the 250 ton patent slipway. Smaller slipways include a boathouse slipway, yacht slip and an unmarked slipway. The cruiser wharf No 2 of 1914 (demolished 1999) is constructed on timber piles and was used to unload items for the island and for fitting out ships built in the yards. Wharf No 3 the Bolt Wharf is a concrete wharf erected in the post war period 1945-60. Destroyer Wharf (demolished 1999) is based on an old stone lined wharf of 1891 below the present timber wharf of c 1914. The nearby Ruby Wharf and Steps is a timber longshore wharf on piles which includes a set of timber steps to water level; the original Ruby steps below the present structure date to c 1853. Other wharves and jetties include Camber Wharf, Timber Wharf, Patrol Boat Wharf, Sutherland Wharf, Old Plate Wharf, Patrol Boat Jetty and New Plate Wharf. Other elements associated with the transport of goods and materials include remnant trolley tracks, tunnels, roads (the Burma Road) and stores tunnels. Cockatoo Island has substantial standing and sub-surface archaeological features associated with the above. Some areas of the island are likely to contain stratified material while other areas of the foreshore may contain buried early structures such as wharves and jetties.[1]

Condition

All but the most significant items of plant and machinery were sold in 1991 and all industrial buildings not of exceptional significance were sold in 1992. The demolition removed some forty buildings from the island, mostly in poor condition. These were mainly warehouse type buildings with pitched roofs, clad in steel. Other demolished structures included ancillary and small industrial buildings. Several other structures are no longer extant including Fitzroy Wharf, Coal Wharf and a number of slipways.[1]

Heritage listing

Cockatoo Island Industrial Conservation Area was listed on the Australian Commonwealth Heritage List on 22 June 2004 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

Criterion A: Processes

Cockatoo Island is important for its association with the administration of Governor Gipps who was responsible for the establishment on the Island of an Imperially funded prison for convicts withdrawn from Norfolk Island in the 1840s; the establishment of maritime activities during the 1840s culminating in the construction of Fitzroy Dock 1851-57 under Gother Kerr Mann, one of Australia's foremost nineteenth century engineers; and the construction of twelve in-ground grain silos following a government order that provision would be made to store 10,000 bushels of grain on the island. The subsequent development of shipbuilding and dockyard facilities has clearly been in response to Federation in 1901, when the New South Wales government took over management of the island; the formation of the Royal Australian Navy in 1911; and the Commonwealth Government 's purchase of the island in 1913. The first steel warship built in Australia, HMAS Heron, was completed on the island in 1916. During World War Two Cockatoo Island became the primary shipbuilding and dockyard facility in the Pacific following the fall of Singapore. Post war development of the facility reflects the importance of the island facility to the Australian Government.[1]

Criterion B: Rarity

Cockatoo Island is the only surviving Imperial convict public works establishment in New South Wales. Individual elements of the convict Public Works Department period include the rock cut grain silos, the Prisoners Barracks and Mess Hall 1839-42, the Military Guard House, the Military Officers Quarters and Biloela House c. 1841. The range of elements associated with the shipbuilding and dockyard facility date from the 1850s and include items of remnant equipment, warehouse and industrial buildings and a range of cranes, wharves, slipways and jetties which illustrate the materials, construction techniques and technical skills employed in the construction of shipbuilding and dockyard facilities over 140 years. Individual elements within the dockyard facility include Fitzroy Dock and Caisson 1851-57, Sutherland Dock 1882-90 the Powerhouse 1918, the Engineer's and Blacksmith's Shop c. 1853 and the former pump building for Fitzroy Dock.[1]

Criterion D: Characteristic values

The industrial character of the cultural landscape of the Island has developed from the interaction of maritime and prison activity and retains clear evidence of both in a number of precincts. The cultural landscape is articulated by man made cliffs, stone walls and steps, docks, cranes, slipways and built forms. Extant structures within the precincts are important for their ability to demonstrate: the functions and architectural idiom and principal characteristics of an imperial convict public works establishment of the 1840s; and the functions and architectural idiom and principal characteristics of the range of structures and facilities associated with the development and processes of the dockyard and shipbuilding industry over a period of 140 years. The range of elements associated with the shipbuilding and dockyard facility date from the 1850s and include items of remnant equipment, warehouse and industrial buildings and a range of cranes, wharves, slipways and jetties which illustrate the materials, construction techniques and technical skills employed in the construction of shipbuilding and dockyard facilities over 140 years.[1]

Criterion H: Significant people

Cockatoo Island is important for its association with the administration of Governor Gipps in the 1840s, the construction of Fitzroy Dock from 1851-57 under Gother Kerr Mann, Federation in 1901, the formation of the Royal Australian Navy in 1911 and the construction of the first steel warship built in Australia, HMAS Heron.[1]

References

Bibliography

- Balint, Emery (1991). "The inventive mind of Gother Kerr Mann". Heritage (Australian Heritage Society). 10 (2): 12–17. ISSN 0155-2716.

- Bastock, John (1975). Australia's ships of war. Angus and Robertson Publishers. ISBN 978-0-207-12927-8.

- Kerr, James Semple (1984). Cockatoo Island, penal and institutional remains : an analysis of documentary and physical evidence and an assessment of the cultural significance of the penal and institutional remains above the escarpment. National Trust of Australia (NSW). ISBN 978-0-909723-39-2.

- Mackay, Godden (1997). Cockatoo Island : conservation management plan. Australian Department of Defence.

- D.W. Muir; K.A.V. Wheeler (1974). Cockatoo Island (Thesis). University of Sydney.

- Parker, R. G. (Roger Grosvenor) (1977). Cockatoo Island : a history. Nelson. ISBN 978-0-17-005208-5.

Attribution

![]() This Wikipedia article was originally based on Cockatoo Island Industrial Conservation Area, entry number 105262 in the Australian Heritage Database published by the Commonwealth of Australia 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 17 September 2018.

This Wikipedia article was originally based on Cockatoo Island Industrial Conservation Area, entry number 105262 in the Australian Heritage Database published by the Commonwealth of Australia 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 17 September 2018.