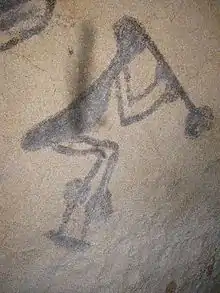

Cohoba is a Taíno transliteration for a ceremony in which the ground seeds of the cojóbana tree (Anadenanthera spp.) were inhaled, the Y-shaped nasal snuff tube used to inhale the substance, and the psychoactive drug that was inhaled. Use of this substance produced a hallucinogenic, entheogenic, or psychedelic effect.[1] The cojóbana tree is believed by some to be Anadenanthera peregrina[2] although it may have been a generalized term for psychotropics, including the quite toxic Datura and related genera (Solanaceae). The corresponding ceremony using cohoba-laced tobacco is transliterated as cojibá. This was said to have produced the sense of a visionary journey of the kind associated with the practice of shamanism.

The practice of snuffing cohoba was popular with the Taíno and Arawakan peoples, with whom Christopher Columbus made contact.[3] However, the use of Anadenanthera spp. powder was widespread in South America, being used in ancient times by the Wari culture and Tiwanaku people of Peru and Bolivia and also by the Yanomami people of Brazil and Venezuela.[4] Other names for cohoba include vilca, cebíl, and yopó. In Tiwanaku culture, a snuff tray was used along with an inhaling tube.

Fernando Ortiz, the founder of Cuban Cultural Studies, offers a detailed analysis of the use of cohoba in his important anthropological work, Contrapunteo cubano del tabaco y el azúcar.[5]

History

Cohoba is also known as yopo.[6][7] Historically, this narcotic snuff was prepared and used by the indigenous people living in South America and the Indians of the Caribbean. Early accounts of it first appeared during the time of Christopher Columbus's exploration, with its first documentation written in 1496 by Ramon Pane—who travelled with Columbus in the second voyage. The name of "cohoba" refers to the finely ground, cinnamon-colored snuff itself, as well as the ceremonial practice using it by South American tribes.[6] Cuiva and Piaroa people of Orinocoan descent commonly consume Cohoba. As a part of important shamanistic rituals, cohoba represents identity and sociality.[8]

The blending step of the plant mixture determines the potency of cohoba, based on the quality of the ingredients and its preparation.[7][8] Cohoba seeds are harvested once they mature, from October to February, such that cohoba can be prepared fresh by shamans throughout the year, when necessary. The bark of the cohoba tree is then collected, with its quality judged by the fineness and whiteness of the powdered ash after burning the bark. Meanwhile, the seeds of the cohoba plant are pulverized and skillfully blended with the powdered bark ash to create a dough resembling butter. Once the desired texture is achieved, the dough is flattened into a cookie and cooked over a fire. Traditionally, yopo is taken by deep inhalation through bifurcated tubes from a special apparatus resembling a slightly deep, concave wooden plate.

Symptoms

Though there are myriad somatic symptoms, ranging from violent sneezing to increased mucus production and bloodshot eyes, cohoba is appreciated for the altered, other-worldly state of consciousness it lends to the user. Even though cohoba is often snuffed with tobacco, it has pharmacologically intriguing properties distinct from tobacco.[9] The active components in cohoba responsible for the hallucinogenic effects are DMT (N,N-dimethyltryptamine) and bufotenine (N,N-dimethyl-5-hydroxytryptamine).[10] The effects of DMT include kaleidoscopic visions similar to LSD that may lead to scenery hallucinations, accompanied by auditory hallucinations. The psychotic effects derived from bufotenine have been suggested to have resulted from central nervous system activity. Though cohoba usage is not as widespread as before, it is still taken up today by various localities of South America for the aforementioned rich, hallucinogenic properties.[7]

References

- ↑ Aquino, Luis Hernández (1977). Diccionario de voces indígenas de Puerto Rico. Editorial Cultural. ISBN 84-399-6702-0.

- ↑ Hallucinogenic Plants by Richard E. Shultes. Golden Press, New York, 1976.

- ↑ The Role of Cohoba in Taino Shamanism. Constantino M. Torres, in Eleusis No. 1 (1998)

- ↑ International, Survival (2008-11-24). "Los yanomami debaten sobre minería y salud". survival.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 2023-08-04.

- ↑ Contrapunteo cubano del tabaco y el azúcar, Additional chapter VIII, Fernando Ortiz (Madrid: Cátedra, 2002).

- 1 2 "Safford/cohoba". www.samorini.it. Retrieved 2020-11-09.

- 1 2 3 Rodd, Robin (September 2002). "Snuff Synergy: Preparation, Use and Pharmacology of Yopo and Banisteriopsis Caapi Among the Piaroa of Southern Venezuela". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 34 (3): 273–279. doi:10.1080/02791072.2002.10399963. ISSN 0279-1072.

- 1 2 Rodd, Robin; Sumabila, Arelis (2011-03-28). "Yopo, Ethnicity and Social Change: A Comparative Analysis of Piaroa and Cuiva Yopo Use". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 43 (1): 36–45. doi:10.1080/02791072.2011.566499. ISSN 0279-1072.

- ↑ McKenna, Dennis; Riba, Jordi (2016), "New World Tryptamine Hallucinogens and the Neuroscience of Ayahuasca", Behavioral Neurobiology of Psychedelic Drugs, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 283–311, ISBN 978-3-662-55878-2, retrieved 2020-11-03

- ↑ Cameron, Lindsay P.; Olson, David E. (2018-10-17). "Dark Classics in Chemical Neuroscience: N , N -Dimethyltryptamine (DMT)". ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 9 (10): 2351. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00101. ISSN 1948-7193.