.jpg.webp)

Coldenhove Castle (Dutch: Kasteel Coldenhove) was a castle in Eerbeek, the Netherlands. Due to its excellent location in the Veluwe, the castle used as hunting lodge by the dukes of Guelders and the princes of Orange. Nothing remains anymore of the castle or its gardens.

A variation on the name is Koldenhoven.

History

Counts and Dukes of Guelders

Around 1300, the counts of Guelders constructed a castle in Coldenhove near Eerbeek. [1] [2] Due to its location on the Veluwe with its excellent hunting grounds, it was primarily used as hunting lodge.[1][2] In 1516, Charles II, Duke of Guelders (1467-1538) sells the castle to his huntsman, Gerrit van Scherpenzeel, landdrost of the Veluwe.[1][2] Together with his son, he creates a small paradise of gardens and ponds around the castle.[1][2] Duke Charles II was so impressed that in 1536 he exchanges his main seat, the castle of Rozendaal, for Coldenhove castle.[1][2][3]

When the duke passed away in 1538, a war started for the succession in Guelders as there was no legitimate heir.[4] Coldenhove castle, however, was inherited by Karel van Gelre tot Coldenhove (1508-1568).[4] One of the two illegitimate sons the duke had with Anna van Roderloo.[4] Their descendants sold the castle and its estate to Gerrit Boshoff in 1611.[4] The Boshoff family owned the castle for most of the seventeenth century.[4][5] In the 1690s, times were difficult and the estate was heavily mortgaged.[4][5] In 1700, the castle was sold to king William III.[4][5]

William III

King-stadtholder William III (1650-1702) was very fond of hunting.[1][2] In his first part of his reign as stadtholder, he spent as much as ten weeks a year hunting in the Veluwe.[1][2] William III and Mary Stuart (1662-1694) had various houses in this area, like the Hof te Dieren and the palace Het Loo.[1][2] Also, their entourage had their seats here like Middachten Castle, Rozendaal castle or de Huis de Voorst.[1][2] In 1700, William acquired Coldenhove.[1][2] William wanted Coldenhove to become as impressive as Het Loo itself.[1][2][6]

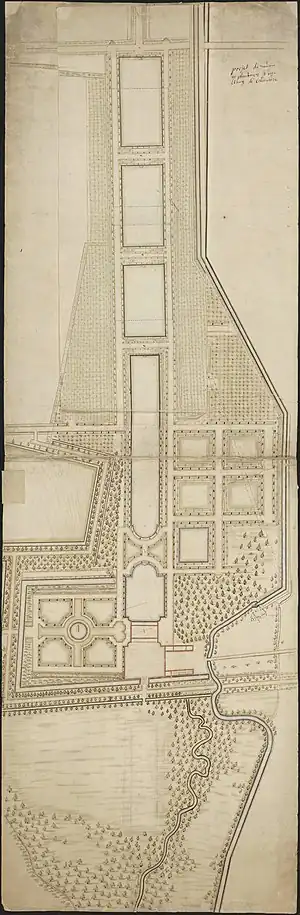

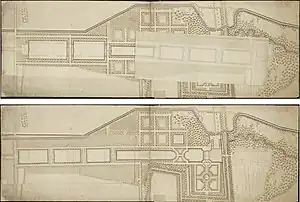

The Dutch national archives contain the design for the impressive gardens around the palace including various large ponds.[1][2][6] Some scholars attribute the plan to the architect Daniel Marot (1661-1752)[1][2][6] Other scholars think that the design has been made by Jan van Arnhem (1636-1716), friend of William III and owner of Rozendael castle, where he designed similar gardens including a similar set of large ponds.[5][7]

During the reconstruction of the castle, it unfortunately burned down in 1701.[1][2][6] It was not reconstructed as the king died due to a horse incident in 1702.[1][2] Some scholars argue that instead of fire, the old castle was demolished and no replacement was constructed due to the early passing of the king.[5] There are no design known how the new castle should have look liked, and if the architect would have been the same. The gardens were (largely) realized and remained intact up to around 1770, when the ponds disappeared.[5]

Until 1795, the estate remained property of the princes of Orange.[1][2] After which, it was confiscated and sold.[1][2] Today, at the location of the castle, there is a paper mill ('Neenah Coldenhove').[1][2][5] Nothing reminds anymore of the palace.[5] Archeological research did not reveal any remains. However, digital elevation research revealed that the landscape still contains traces of the former gardens.[5] This primarily concerns the pond basins.[5]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Vredenberg, Jan, ed. (2013). Kastelen in Gelderland (in Dutch). Utrecht: Uitgeverij Matrijs. p. 185. ISBN 978-90-5345-410-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 "History of Coldenhove by Eerbeek". www.gelderland.nl. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ↑ Bierens de Haan, J.C. (1994). Rosendael Groen Hemeltje op Aerd (in Dutch). Zutphen: Walburg Pers. p. 13. ISBN 90-6011-870-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "History of the Bosshof family". boshoffs.weebly.com. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Veldhuis, Maarten; Holwerda, Jan (2020). "De Huiskampspreng, spil van de tuinaanleg van Coldenhove". Wijerd (in Dutch). Bekenstichting: 29–35.

- 1 2 3 4 Ronnes, Hanneke; Haverman, Merel (2020). "A Reappraisal of the Architectural Legacy of King-Stadholder William III and Queen Mary II: Taste, Passion and Frenzy". The Court Historian. 25:2: 158–177.

- ↑ Bierens de Haan, J.C. (1994). Rosendael Groen Hemeltje op Aerd (in Dutch). Zutphen: Walburg Pers. pp. 76, 80–81. ISBN 90-6011-870-7.

Literature

- Blom, W; Brink, C (1993). "De Eerbeekse Beek - 9. Geschiedenis landgoed Coldenhove (Coldenhave)". De Marke (in Dutch). Oudheidkundige vereniging De Marke. 1993–1: 65–70.

- Bierens de Haan, J.C. (1994). Rosendael Groen Hemeltje op Aerd (in Dutch). Zutphen: Walburg Pers. pp. 76, 80–81. ISBN 90-6011-870-7.

- Keunen, Luuk (L.J.); Willemse, N.W. (2009). Beekherstel Eerbeekse beek fase 2, gemeente Brummen. Een cultuurhistorisch bureauonderzoek met verkennende boringen in het kader van archeologisch vooronderzoek. RAAP Report 2029 (Report) (in Dutch). Weesp: RAAP Archeologisch Adviesbureau.

- Vredenberg, Jan, ed. (2013). Kastelen in Gelderland (in Dutch). Utrecht: Uitgeverij Matrijs. p. 185. ISBN 978-90-5345-410-7.

- Veldhuis, Maarten; Holwerda, Jan (2019). "De tuinaanleg van Coldenhove, niet alleen ontworpen maar ook uitgevoerd" (PDF). Cascade bulletin voor tuinhistorie (in Dutch). 28: 74–86.

- Ronnes, Hanneke; Haverman, Merel (2020). "A Reappraisal of the Architectural Legacy of King-Stadholder William III and Queen Mary II: Taste, Passion and Frenzy". The Court Historian. 25:2: 158–177.

- Veldhuis, Maarten; Holwerda, Jan (2020). "De Huiskampspreng, spil van de tuinaanleg van Coldenhove". Wijerd (in Dutch). Bekenstichting: 29–35.

- Veldhuis, Maarten; Holwerda, Jan (2021). "De Huiskampspreng, spil van de tuinaanleg van Coldenhove". De Marke (in Dutch). Oudheidkundige vereniging De Marke. XLV-1: 24–33.

External links

- "History of Coldenhove by Eerbeek". www.gelderland.nl. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- "Coldenhove castle". www.kasteleninnederland.nl. Retrieved 27 March 2023.