Coldharbour Mill, near the village of Uffculme in Devon, England, is one of the oldest woollen textile mills in the world, having been in continuous production since 1797. The mill was one of a number owned by Fox Brothers, and is designated by English Heritage as a Grade II* listed building.[1]

Location

Coldharbour Mill can be found just off junction 27 of the M5 motorway near the village of Uffculme, and near to the border with Somerset. The headquarters for the mill was at Tonedale in Wellington. The water provided by the nearby River Culm was a prime factor in Thomas Fox's decision to purchase the existing grist mill. In 1797, he wrote to his brother "I have purchased the premises at Uffculme for eleven hundred guineas, which I do not think dear as they include about fifteen acres of very fine meadow land. The buildings are but middling, but the stream good."[2] The roads in the area at the time were very poor, and finished cloth had to be carried by pack horses to the nearby ports of Topsham and Exeter, or by carrier's cart to Bridgwater, Bristol and London (a twelve-day journey).

History

It appears that there has been a mill of some description near the Coldharbour site since Saxon times. The Domesday Book recording two mills in the Uffculme area.[3]

At its peak the company employed approximately 5,000 people and owned and operated nine mills and factories in Somerset, Devon, and Oxfordshire. One of the most notable satellite mills was that of William Bliss & Sons, built in 1872 after a disastrous fire in the original mill. Located in Chipping Norton, the William Bliss site was one of the grandest mills in England, complete with reading room, chapel and workers cottages. Fox Brothers bought it in 1920.

The main Tonedale site in Wellington was the largest integrated mill site in the South West of England, covering 10 acres of land and forming the hub of the Fox Brothers woollen manufacturing 'empire'. It is believed to have been the only 'Twin Vertical Woollen Factory' in the world - that is, making both worsted and woollen products, and controlling the entire process from fleece to finished cloth in-house.

The founders

The ancestors of the mill owners, the Fox family (no relation to George Fox, founder of the Religious Society of Friends, or Quakers) and the Were family, were early Quaker converts. During George Fox's first visit to Devonshire in 1655, he went to the house of Nicholas Tripe and his wife, who became 'convinced'.[4] Their daughter, Anstice, married George Croker of Plymouth, and they were much persecuted for their beliefs.[5] Their daughter Tabitha married Francis Fox of St. Germans, Cornwall, a serge maker. The family remained in Cornwall, becoming merchants and shipping agents, and in 1745 the grandson of Francis and Tabitha, Edward Fox of Eggeshall near Wadebridge, married Anne Were, the daughter of a Wellington serge maker, Thomas Were. (In 1749, Edward's cousin, George Croker Fox, married Mary Were, the sister of Anne). Thomas Were was a very successful manufacturer, and had inherited the WRE trademark, which certified the quality of his cloth.[6] His great-great grandfather John Were of Pinksmoor was credited with owning a fulling mill. During one of the visits of Edward to his father-in-law, it was suggested that one of Edward and Anne's sons should join the Wellington woollen manufacturing business.[2] After four years of study overseas, Edward's son Thomas Fox moved to Wellington, and became a partner of Were and Company in 1772, aged 25. Thomas and his wife Sarah Smith, built in 1801, then lived in, Tone Dale House, Wellington - the house is still lived in by a Fox, five generations later, by Ben and Victoria Fox. In 1826, when his sons were partners (the Weres having relinquished their shares), the business was renamed Fox Brothers.

The family were prominent in local affairs, and subscribed £1,044 5s 6d in shares in the Grand Western Canal between 1809 and 1813,[6] Thomas having considered the original proposal of 1792 with considerable reticence: "People hereaway seem now as much too eager to engage in Canals as they have been too backward for many years. The almost incredible sum of £900,000 was lately subscribed at Wells in about two hours for cutting one from Taunton to Bristol. Whilst this delyrium continues the writer is neither disposed to subscribe himself nor to recommend his friends doing it, as he doubts whilst such money pours in on them in such abundance it may be badly husbanded."[2]

Banking

In 1787, Were and Company ran short of ready cash, and decided to print their own bank notes - effectively "promises to pay". On 30 October, Thomas printed 500 notes of five guineas each. The notes were well received by local businesses. In 1797, an invasion scare resulted in a shortage of gold and cash, and Thomas Fox issued 3,000 five guinea notes, and seventy six £20 notes in order to enable his business to continue its expansion.[2]

The Fox, Fowler and Company bank eventually had over fifty branches in the West Country, and was authorised to issue its own bank notes until 1921, the year it was taken over by Lloyds Bank - itself founded by a Quaker, Sampson Lloyd. One of the original £5 notes is on display at Tone Dale House, the family home which Thomas Fox built, in 1801.

Textile products

Exeter was the centre of the mediaeval woollen trade in England, with cloth being exported to the Continental markets of France, Holland and Germany. Kersey, a sturdy cloth, was superseded by serge, so that by 1681 95% of the Exeter cloth export was serge.[7] As already mentioned, the Were family were major suppliers of serge cloth to the Continent, especially Holland. Whilst using the ports of London and Bristol as well, Topsham was a major port for the Were export trade. We have a contemporary description of the Exeter trade in serge by Celia Fiennes (1662–1741):

There is an Increadible quantety of [serges] made and sold in the town. There market day is Fryday ... the Large Market house set on stone pillars, wch runs a great Length on wch they Lay their packs of serges. Just by it is another walke wth in pillars wch is for the yarne, the whole town and Country is Employ'd for at Least 20 mile round in spinning, weaveing, dressing and scouring, fulling and Drying of the serges. It turns the most money in a weeke of any thing in England. One weeke with another there is 10000 pound paid in ready money, Sometymes 15000 pound. The weavers brings in their serges and must have their money wch they Employ to provide them yarne to goe to work againe.[8]

However, the French Revolution and the invasion of Flanders in 1793 caused very serious difficulties for Exeter cloth merchants, and in 1794 the Weres were forced to cancel major worsted yarn orders.[9]

Napoleon's Italian campaigns of 1796-7 closed the Italian market for English cloth, and then Spain entered the war as an ally of France, leading to the confiscation of Exeter cloth. Only six vessels cleared from the Exe with cloth in 1797, and two in 1798; a far cry from the 1768 despatch of 330,414 pieces of cloth.[7] Some Exeter merchants, such as Barings, moved to London - the Weres changed production to long ells, a fine white serge, for the East India Company. A letter from Thomas Fox to Green and Walford, factors, is to be found in the Fox Brothers Letter Book archive:

Wellington, 15th seventh month 1788 We have for a great number of years been engaged in a very considerable manufactory of various export articles, the principal of which is mixt serges for Holland, but finding of late a slackness in demand owing to the troubles in that country, and the introduction of cottons and other articles, we see it necessary to turn part of our attention to some other articles of constant demand and Long Ells appear to us the most eligible. We hope if a tryal appears to answer we may in time prove mutually useful correspondents.[2]

With the termination of the monopoly of the East India Company's charter in 1833 through the Government of India Act 1833 (3 & 4 Will. 4 c. 85), the trade in long ells to China declined, and Thomas Fox developed the production of flannel, which was sold in the home market and to America. Following his Quaker beliefs, Thomas Fox refused to sell flannel to the East India Company when he heard it would be used in the manufacture of cartridges. In 1881, as a result of losses in the First Boer War, a Parliamentary Commission sought to equip the army with khaki uniform. Fox Brothers decided to bid for the contract, reasoning that the new contract for 5,000 puttees would save lives, as well as create employment. Fox Brothers went on to be the major producer of puttees, manufacturing some 850 miles of the cloth in World War I.

In support of the flannel emphasis, in 1865 Coldharbour Mill moved over to producing worsted yarn rather than woollen yarn. This necessitated the need for more power to drive new combing machines. (Worsted yarn is made from sheep with long hair fleeces and the wool has to be combed to ensure that all the fibres are parallel.)

Coldharbour Mill classifies itself as "a working wool museum" and as such runs its museum machinery to demonstrate how woollen products were made. The demonstration products (including worsted yarn, tartan cloth, and rugs) are made available for sale. The mill has four registered tartans - Devon Original (1284), Devon Companion (1283), Somerset (831), and Blackdown Hills (6711).[10]

Architecture

English Heritage wrote a Historic Buildings Report (B/065/2001) about the mill complex, and described the site as "probably one of the best-preserved textile mill complexes in the country. It retains the full range of buildings and power system features which characterised the development of the 19th century textile mill with much of the machinery that was used at the site in the 20th century."[11]

Coldharbour Mill was primarily always used for the production of wool yarn for the weaving frames of the Wellington mill. The original grist mill was probably a three-storey building, and the original sale notice of 1788 states "The Stream divides in two Parts, one at each End of the House, and they are in a Manner two separate Mills, under the same Roof".[12] A legal dispute of 1834 [13] contains a detailed map of the water courses, which are in their existing positions, with a leat to the front and rear of the grist mill.

The foundations of the main mill were mentioned in a letter of 15 April 1799, stating that they were 50 feet from the grist mill - further away than the current building, but at a point where the wall is thicker today. The mill building of 39 feet wide by 123 feet long was very large for its time. Thomas Fox wrote to his machinery supplier describing how the new mill building was to operate:

Wellington 7th third month 1799 I find in my work here that a single carder supplies two billies and each billy three jennies. I wish therefore to make my building three stories high and on each floor to place one scribbler, two single or double carders, four billies, two on each side the creeper, and twelve jennies, and to place the water wheel nearly at one end so as at any time to add to it another building of like dimensions.[2]

An inventory of 1802 suggests that spinning was to be carried out on hand-powered spinning jennies, with a waterwheel (costing £450) powering the carding machines. By 1816 the mill contained worsted spinning frames, and in 1822 a new waterwheel costing £1,500 had been installed.

The main mill building was expanded at various times, with a two-story extension added to the north; a fireproof stone staircase to the east; a wheelhouse; a fourth floor to the main building; and an adjacent combing shed built over the tail race leat flowing from the waterwheel.

Steam power came to the mill in three major building phases. In 1865 a beam engine house was built, together with a boiler house and the first chimney on the site. In the 1890s a second beam engine arrived, the boiler house was extended and the existing chimney built, and then in 1910 the existing horizontal engine was fitted, the Green's economiser house added and the boiler house extended again.

The mill site contains a wide variety of subsidiary buildings, including stabling, a linhay, a gas retort house (see below), a carpenter's workshop, an air raid shelter from WWII, worker's cottages, and the manager's house. The tail race which takes the water away from the waterwheel is unusual in that it runs under the combing shed in a wide culvert, before briefly reappearing and then running underground again for some 200 metres.

Sources of power

Coldharbour Mill is unusual to have used both water and steam power right up to the time of its demise as a commercial venture. The water power was believed to have been used for the night shift up until 1978.[14]

Water power

The English Heritage report states "it is possible that the wheel pit and parts of the wheel itself are the remnants of the new wheel which was recorded in the Stock Book of 1822...and should be considered of considerable historic significance".[11] The cast and wrought iron high breast-shot wheel is 18 feet in diameter by 14 feet wide, with 48 buckets. It is part of a very unusual survival of a combined water and steam powered drive system, as it continued to be used after the 1910 addition of the horizontal steam engine, and the drive mechanism is still in place. The wheel is turning most days.

Steam power

Thomas Fox's brother Edward was part owner of a Cornish mine, and was instrumental in installing an early example of a Boulton and Watt engine. Edward told Thomas about this new technology, with the result that James Watt was invited to Wellington in 1782, just six months after his patent for the sun and planet gear that allowed reciprocating motion. Thomas missed the meeting, but wrote to him afterwards:

Wellington 25th fourth month 1782 I was very sorry to miss the opportunity of seeing thee when so obliging as to call on us at my brothers request, with whom I had lately been conversing on some proposed improvement of thine for stamping mills, to be worked by steam with a very small quantity of fire. I hinted to him my apprehensions that the same principle might be applied to fulling mills and rendered very extensively useful when water was scarce...On thy return through this country it would be esteemed a particular favour couldst thee favour us with a day or two of thy company.[2]

However, the visit came to nothing, partly due to the very high cost of coal, and partly due to the discontent about mechanisation, which would culminate in the later Luddite Movement. A letter in 1785 from Thomas states

We do not much wonder at manufacturers being individually fearful of introducing new machines, since, however useful, the first promoters usually suffer from popular violence without being sufficiently protected by the laws."[2]

Thus it was that the first mechanised wool spinning machinery, purchased from Backhouse of Darlington, were powered by horses. These arrived in September 1791, bringing the Industrial Revolution to the West Country. It was evident from a letter of 1786 that Thomas wished he could have had a cheap source of coal, as in those parts of the country fed by canals:

When we consider the situation in this part of the country and what distresses our poor sufferer for want of fuel and how many manufactures for that reason cannot be carried on, we lament the fact that the fine coal which abounds in the Mendippe Hills is not rendered more generally useful by some navigable cuts through a country they would at the same time help to drain.[2]

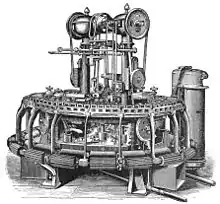

Although the Wellington mill purchased a steam engine for £90 (and a £20 boiler) in 1840,[6] Coldharbour Mill did not get a steam engine until 1865, by which time the Bristol and Exeter Railway was supplying cheap coal to Tiverton Junction. The mill has two Lancashire boilers in the boiler house, only one of which is still operational. Initially a 25 hp beam engine was installed, followed by a second beam engine in the 1890s (possibly 1896). A Pollit & Wigzell 300 hp, cross compound engine superseded the beam engines in 1910 and continued in use, along with the water wheel, until Fox Brothers closed the mill in April 1981. Today the cross compound steam engine[15] remains fully operational and runs regularly at steam up weekends. It drives the shafting on all five floors of the mill via an operational rope drive. In 1993 a salvaged 1867 Kittoe and Brotherhood beam engine was painstakingly restored and installed[16] at the mill, in one of the disused beam engine sheds.

The mill contains a number of other steam powered exhibits, including a working Ashworth fire pump, already at Coldharbour, but repaired in 1984 with components from Bliss Mill; a very rare example of a low pressure wagon boiler dating from the late 1700s; and a (non-operational) steam powered flue fan.

Electrical power

Coldharbour Mill also had a small water turbine for electricity generation, which used the 14 foot head of water between the upper leat and the tail race. No references have been found to it in any register of Devon hydro-electric schemes, and it was unlikely to have generated any more than 3 kW peak power. The exit is visible today in the tail race leat, but nothing else is believed to exist.

Two generators were installed in the beam engine house after the beam engines were removed and these were driven by the Pollit and Wigzell engine. The flat belt pulley system is still in existence. It is believed that this was used for lighting rather than running the machines.

Gas production

Coldharbour Mill generated its own coal gas on site for lighting the mill (and thus enabling the machinery to be run all night). Although the retorts have been removed and disposed of, the Gas Retort house which housed the retort bench is still standing. In fact, the original gas retorts have been discovered in the leat, where they served as weir components. English Heritage classifies the late 19th century Gas Retort House as a very rare survival of gas-making facilities.

Textile machinery

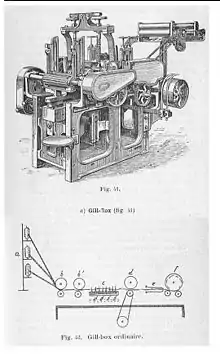

At the time of its closure in April 1981, Coldharbour Mill still had its textile machinery in position. The majority of these machines have been preserved (though not all are exhibited), and have been augmented with weaving machines rescued from the closure of the Tonedale site. The lowest part of the site, the level 1 combing shed, dealt with the initial cleaning and combing of the unwashed wool. The process involved a number of separate stages, each with a specialised machine. The eight opening gill machines (made by Taylor Wadsworth & Co.) opened up the fleeces and prepared the wool for washing in a large back-washer with steam heated rollers. Following the washing, further gill boxes produced successively combed fibres, which were passed to a circular Noble combing machine. This machine separated the fibres into long "Tops" and the short poor quality fibres. Although these machines are preserved on site, they are no longer in use today. British wool tops are purchased in, dyed into standard colours, and then up to ten strands of tops are fed into the Intersecting Gill Box (manufactured by Prince Smith and Stells in 1959). The gill box starts the process of drawing out the fibres, and also enables new colours to be created by blending together the standard colours. The output of the gill box is termed a sliver. This particular machine has a mechanism to ensure the weight of the sliver is constant, which is important to ensure the final yarn thickness is constant. The next process is to draw the slivers out further, and to give the fibres a small twist to strengthen the resulting slubbing such that it can be wound onto a bobbin. At Coldharbour Mill, this is demonstrated on a Price Smith and Stells draw box of 1959. The bobbins from this machine are then placed in a further draw box by Prince Smith and Stells, this time an 1898 machine, and the thread from a pair of bobbins is drawn out to a seventh of its diameter, and given a light twist. If this output is to be used for Aran yarn production, it is termed a roving, and is sent on to the spinning frame. However, if the slubbing is for double knitting yarn, the slubbing must go through another reduction on a draw box.

The museum today

The museum is owned and run by a not-for-profit charitable trust, Registered Charity No. 1123386. It has a number of educational programmes for schools including Victorian Drama; Materials & Fibres; and Britain at War.

The mill is home to a number of other exhibits:

- A World War II exhibit

- Extensive displays on puttee manufacturing

- The West Country Historic Omnibus & Transport Trust archive

- Visiting exhibitions

References

- ↑ Historic England. "COLDHARBOUR MILL (1106486)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Fox, Hubert Quaker Homespun, The Life of Thomas Fox of Wellington, Serge Maker and Banker 1747-1821 privately printed

- ↑ Powell-Smith, Anna. "Uffculme - Domesday Book". Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ↑ Fox, Hubert The Beginning of Quakerism in Devon and Cornwall Privately printed 1985

- ↑ Besse, Joseph A Brief Account of many of the prosecutions of the people call'd Quakers Sowle, London 1736

- 1 2 3 Fox, Joseph Hoyland The Woollen Manufacture at Wellington, Somerset. Compiled from the Records of the Old Family Business Arthur Humphreys, London 1914

- 1 2 Clark, E.A.G. The ports of the Exe estuary 1660-1860 University of Exeter 1960

- ↑ "Vision of Britain - Celia Fiennes - 1698 Tour: Bristol to Plymouth".

- ↑ Letter to James Hopwood of St Austell dated 1 October 1796 (175 Years, pamphlet privately printed for Fox Bros., Wellington, 1947 p8).

- ↑

- 1 2 Williams, Mike Coldharbour Mill Historic Buildings Report (B/065/2001) English Heritage 2001

- ↑ Exeter Flying Post 4 December 1788

- ↑ Documents relating to 1834 arbitration, including Plaintiff's map, Devon Records Office, 74B/ME98

- ↑ Hall, David and Dibnah, Fred Fred Dibnah's Age of Steam Random House 2013

- ↑ "Coldharbour Steam Group Pollit and Wigzell mill engine". Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ↑ "Beam Engine". Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2014.