| Walter E. Kurtz | |

|---|---|

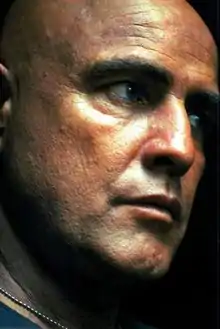

Marlon Brando as Colonel Kurtz in Apocalypse Now | |

| First appearance | Apocalypse Now (1979) |

| Created by | |

| Based on | Kurtz from Heart of Darkness |

| Portrayed by | Marlon Brando |

| In-universe information | |

| Alias |

|

| Gender | Male |

| Occupation | |

| Spouse | Janet Kurtz |

| Children | 1 son |

| Nationality | American |

Colonel Walter E. Kurtz, portrayed by Marlon Brando, is a fictional character and the main antagonist of Francis Ford Coppola's 1979 film Apocalypse Now. Colonel Kurtz is based on the character of a nineteenth-century ivory trader, also called Kurtz, from the 1899 novella Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad.

Fictional biography

Walter Kurtz was a career officer in the United States Army; he was a third-generation West Point graduate who had risen through the ranks and was seen to be destined for a top post within the Pentagon. A dossier read by the narrator, Captain Willard, implies that Kurtz saw action in the Korean War after receiving a master's degree in history from Harvard University. He later graduated from the US Army Airborne School.[1]

In 1964, the Joint Chiefs of Staff sent Kurtz to Vietnam to compile a report on the failings of the current military policies. His overtly critical report, dated March 3, 1964, was not what was expected and was immediately restricted for the Joint Chiefs and President Lyndon B. Johnson only.

On May 11, August 28, and September 23, 1964, 38-year-old Kurtz applied for Special Forces, which was denied out of hand because his age was too advanced for Special Forces training. Kurtz continued with his ambition and even threatened to quit the armed forces, when finally his wish was granted and he was allowed to take the airborne course. Kurtz graduated in a class where he was nearly twice the age of the other trainees and was accepted into the Special Forces Training, and eventually into the 5th Special Forces Group.

Kurtz returned to Vietnam in 1966 with the Green Berets and was part of the hearts and minds campaign, which also included fortifying hamlets. On his next tour, Kurtz was assigned to Project GAMMA, in which he was to raise an army of Montagnards in and around the Vietnamese–Cambodian border to strike at the Viet Cong (VC) and North Vietnamese Army (NVA). Kurtz located his army, including their wives and children, at a remote abandoned Cambodian temple which Kurtz's team fortified. From their base, Kurtz led attacks on the local VC and the regular NVA in the region.

Kurtz employed barbaric methods not only to defeat his enemy but also to send fear. At first Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) did not object to Kurtz's tactics, especially as they proved successful. This soon changed when Kurtz allowed photographs of his atrocities to be released to the world.

In late 1967, after Kurtz failed to respond to MACV's repeated orders to return to Da Nang and resign his command after he ordered the summary execution of four South Vietnamese intelligence agents whom he suspected of being double agents for the Viet Cong, the MACV sent a Green Beret Captain named Richard Colby to bring Kurtz back from Cambodia. Either because he was brainwashed or because he felt a sympathy towards Kurtz's cause, Colby joined up with Kurtz instead of bringing him back to Da Nang.

With Colby's failure, MACV then selected Captain Benjamin L. Willard, a paratrooper and Army intelligence officer, to journey up the Nung river and kill Kurtz. Willard succeeded in his mission only because Kurtz, himself broken mentally by the savage war he had waged, wanted Willard to kill him and release him from his own suffering. Kurtz also murdered Jay "Chef" Hicks by severing his head. Before Willard killed him, Kurtz asked Willard to find Kurtz's wife and son, and explain truthfully to them what he had done in the war.

Personality

Well, you see Willard, in this war, things get confused out there: power, ideals, the old morality, practical military necessity. But out there with these natives, it must be a temptation to be god, because there's a conflict in every human heart, between the rational and the irrational, between good and evil, and good does not always triumph. Sometimes, the dark side overcomes what Lincoln called the better angels of our nature. Every man has got a breaking point. You and I have one. Walter Kurtz has reached his, and very obviously, he has gone insane...

— Lt. Gen. Corman describing Kurtz to Willard, Apocalypse Now (1979)

Ever since he was in the US Army, Kurtz was always a patriotic soldier for his nation, thinking on how to achieve victory in the Vietnam War by any kind of means. Seemingly a kindhearted man, Kurtz eventually reached his "breaking point" according to Gen. Corman's words. This point led him to betray the US Army following his dismissal, yet, he was a career-full soldier, fully serving his nation in any means. However, his breaking point led him to become a completely cold, psychopathic, maniacal and above all manipulative individual, aiming to use his "unsound" methods to make sure his nation would win the war, even though he was using those methods to brutally torture Vietnamese people, nearly to death, yet, he was not a sadist but a bold individual, using his boldness to ensure USA's triumph. General Corman describes Kurtz to have originally been a good man, the kind of person who is filled with kindness including the capability of seeing the difference between good and evil.

Often ruthless, Kurtz has an extremely complex personality, to the point of being nearly inexplicable. When he rose to power as the "God-King" of the Montagnards, Kurtz was treated truly like a godlike king, using his extensive military training to form an army of followers and soldiers around him, eventually becoming a philosopher of war, reading poetry and quotes from the Holy Bible, leading him to be seen as truly insane.

The photojournalist "Jack" is the first American to meet Kurtz after his transformation into a crazed megalomaniac, yet he describes him as a great man, and, as a man who reads poetry "out loud". His ruthless nature can be seen in photos presented to Willard, in which Kurtz had used his own men to kill or torture Vietnamese people, however, his truly ruthless nature comes to light when he tortures Willard physically by capturing him at a bamboo-like prison booth, as well as mentally by showing him the severed head of his friend Chef, whom he had killed.

Inspiration

Colonel Kurtz is based on the character of a 19th-century ivory trader, also called Kurtz, from the novella Heart of Darkness (1899) by Joseph Conrad.

The movie's Kurtz is widely believed to have been modeled after Tony Poe, a highly decorated and highly unorthodox Vietnam War-era paramilitary officer from the CIA's Special Activities Division.[2] Poe was known to drop severed heads into enemy-controlled villages as a form of psychological warfare and to use human ears to record the number of enemies his indigenous troops had killed. He would send these ears back to his superiors as proof of his efforts deep inside Laos.[3][4]

However, Coppola denies that Poe was a primary influence. He maintains the character was loosely based on Special Forces Colonel Robert B. Rheault, whose 1969 arrest for the murder of a suspected double agent generated substantial news coverage.[5]

Portrayal

By early 1976, Coppola had persuaded Marlon Brando to play Kurtz, for a fee of $2 million for a month's work on location in September 1976. Brando also received 10% of the gross theatrical rental and 10% of the TV sale rights, earning him around $9 million.[6][7]

When Brando arrived for filming in the Philippines in September 1976, he was dissatisfied with the script; Brando didn't understand why Kurtz was meant to be very thin and bald, or why the character's name was Kurtz and not something like Leighley. He claimed, "American generals don't have those kinds of names. They have flowery names, from the South. I want to be 'Colonel Leighley'." And so, for a time the name was changed under his demand.[8]

When Brando showed up for filming he had put on about 40 pounds (18 kg) and forced Coppola to shoot him above the waist, making it appear that Kurtz was a 6-foot 6-inch (198 cm) giant.[9] Many of Brando's speeches were ad-libbed, with Coppola filming hours of footage of these monologues and then cutting them down to the most interesting parts.[10]

Filming was put on a week-long hiatus so that Brando and Coppola could resolve their creative disputes. It is claimed that someone left Conrad's source text, which Coppola had repeatedly referred to Brando but which Brando had never read, in the houseboat where Brando was staying at the time. Brando returned to filming with his head shaved, wanting to be "Kurtz" once again; claiming it was all clear to him now that he had read Conrad's novella.[11]

Still photographs of Brando in character as Major Penderton, in the film Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967), were used later by the producers of Apocalypse Now, who needed photos of a younger Brando to appear in the service record of the younger Colonel Walter Kurtz.[12]

As inspiration source

- Stephen King's 2001 novel Dreamcatcher features an antagonist by the name of Abraham Kurtz who is clearly based off Brando's performance. The character was portrayed by Morgan Freeman in the 2003 film adaptation.

- One of the inspirations Iron Man 3 (2013) director Shane Black had for Trevor Slattery, his version of the Mandarin portrayed by Ben Kingsley, was Brando's Kurtz.[13]

- Josh Brolin based his portrayal of the villain Thanos in the Marvel Cinematic Universe on Brando's portrayal as Kurtz.[14][15]

- The character's appearance partially inspired that of Luke Skywalker in The Last Jedi (2017).[16]

- Stellan Skarsgård's portrayal of Vladimir Harkonnen in Dune (2021) was inspired by Brando's performance and the impression the character makes.[17]

- In World Wrestling Entertainment, The "Tribal Chief" storyline, involving Universal Champion Roman Reigns as its leader, is – according to on-screen manager Paul Heyman – based on Apocalypse Now and Kurtz. [18]

References

- ↑ "Quotes for Captain Benjamin L. Willard (Character) from Apocalypse Now 1979". IMDb. 2014. Archived from the original on April 10, 2015. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- ↑ Leary, William L. Death of a Legend. Air America Archive.

- ↑ Warner, Roger (1996). Shooting at the Moon: The Story of America' Clandestine War in Laos. South Royalton: Steerforth Press. ISBN 1-883642-36-1.

- ↑ Ehrlich, Richard S. (July 8, 2003). "CIA operative stood out in 'secret war' in Laos". Bangkok Post. Archived from the original on August 6, 2009. Retrieved June 10, 2007.

- ↑ Isaacs, Matt (November 17, 1999). "Agent Provocative". SF Weekly. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ↑ "New York Sound Track". Variety. November 21, 1979. p. 37.

- ↑ Ascher-Walsh, Rebecca (July 2, 2004). "Millions for Marlon Brando". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ↑ Perry, Kevin EG (August 9, 2019). "Francis Ford Coppola: 'Apocalypse Now is not an anti-war film'". The Guardian. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ↑ "Apocalypse Now Trivia". IMDB. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ↑ "Behind-The-Scenes Stories About Marlon Brando In 'Apocalypse Now'". Ranker.com. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ↑ Ondaatje, Michael (2002). The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-1-4088-0011-9.

- ↑ "Reflections in a Golden Eye". Stylus Magazine. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ↑ Doty, Meriah (March 5, 2013). "'Iron Man 3': The Mandarin's origins explained!". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on March 13, 2013. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ↑ "Josh Brolin hints at Thanos' return and the inspiration for his Marvel movie role". www.digitaltrends.com. August 8, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- ↑ "Marvel: Josh Brolin To Channel Marlon Brando In Avengers Thanos Performance". International Business Times UK. August 8, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- ↑ Szostak, Phil (December 15, 2017). The Art of Star Wars: The Last Jedi. Abrams Books. p. 28. ISBN 9781419727054.

- ↑ "Dune Co-Costume Designer Bob Morgan Goes Back In Time For The Future [Interview]". November 4, 2021. Archived from the original on April 28, 2022.

- ↑ Reedy, Joe (March 30, 2023). "Hail to the Chief: Inside Roman Reigns' 3 years as WWE champ". Associated Press. Retrieved April 3, 2023.