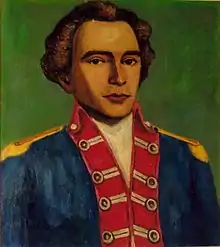

William Crawford | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 2, 1722 Spotsylvania County, Virginia |

| Died | June 11, 1782 (aged 59) Upper Sandusky, Ohio |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Unit | 7th Virginia Regiment |

| Battles/wars | |

William Crawford (September 2, 1722 – June 11, 1782) was an American military officer and surveyor who worked as a land agent for George Washington. Crawford fought in the French and Indian War and the American Revolutionary War. He was tortured and burned at the stake by American Indians during the Crawford expedition in retaliation for the Gnadenhutten massacre, which saw 96 Christian Munsee massacred by the Pennsylvania Militia on March 8, 1782.

Early career

Crawford was born on September 2, 1722, in Westmoreland County, Virginia.[1] Before a 1995 genealogical study by Allen W. Scholl, his birth year was erroneously estimated to be 1732.[2] He was a son of William Crawford Sr and his wife Honora Grimes,[3] who were Scots-Irish farmers. William Crawford Sr was a Presbyterian of Scottish descent from Coleraine, Ireland in what is today Northern Ireland and Honora Grimes was a Presbyterian of Scottish descent from Ballymoney, Ireland in what is today Northern Ireland. After his father's death in 1736, Crawford's mother married Richard Stephenson. Crawford had a younger brother, Valentine Crawford, plus five half-brothers and one half-sister from his mother's second marriage.[4]

In 1742 Crawford married one Ann Stewart, with whom he had one child, a daughter also named Ann, in 1743. Apparently she died in childbirth or soon after, and on January 5, 1744, he married Hannah Vance, said to have been born in Pennsylvania in 1723. They had a son named John (April 20, 1744 – September 22, 1816; he married one Effie Grimes) and at least two daughters, Ophelia "Effie" (September 2, 1747 – 1825, who married Captain William McCormick [February 2, 1738–August 15, 1816][5]), and Sarah (1752–10 Nov 1838, who married 1) Major William Harrison [c 1740–13 June 1782], and 2) Lt. Col Uriah Springer [18 Nov 1754–21 Sep 1826]}. There may also have been another daughter, Nancy, born in 1767, who had apparently died when he wrote his will in 1782.[6]

In 1749, Col. William Crawford became acquainted with George Washington, then a young surveyor somewhat younger than Crawford. He accompanied Washington on surveying trips and learned the trade. In 1755, Crawford served in the Braddock expedition with the rank of ensign. Like Washington, he survived the disastrous Battle of the Monongahela. During the French and Indian War, he served in Washington's Virginia Regiment, guarding the Virginia frontier against Native American raiding parties. In 1758, Crawford was a member of General John Forbes's army which captured Fort Duquesne, where Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, now stands. He continued to serve in the military, taking part in Pontiac's War in 1763.

In 1765 Crawford built a cabin on the Braddock Road along the Youghiogheny River in what is now Connellsville, Fayette County, Pennsylvania. His wife and three children joined him there the following year. Crawford supported himself as a farmer and fur trader. When the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix with the Iroquois opened up additional land for settlement, Crawford worked again as a surveyor, locating lands for settlers and speculators. Governor Robert Dinwiddie had promised bounty land to the men of the Washington's Virginia Regiment for their service in the French and Indian War. In 1770 Crawford and Washington travelled down the Ohio River to choose the land to be given to the regiment's veterans. The area selected was near what is now Point Pleasant, West Virginia. Crawford also made a western scouting trip in 1773 with Lord Dunmore, Governor of Virginia. Washington could not accompany them because of the sudden death of his stepdaughter.[7]

At the outbreak of Dunmore's War in 1774, Crawford received a major's commission from Lord Dunmore. He built Fort Fincastle at present Wheeling, West Virginia.[8] He also led an expedition which destroyed two Mingo villages (near present Steubenville, Ohio) in retaliation for Chief Logan's raids into Virginia.

Crawford's service to Virginia in Dunmore's War was controversial in Pennsylvania, since the colonies were engaged in a bitter dispute over their borders near Fort Pitt. Crawford had been a justice of the peace in Pennsylvania since 1771, first for Bedford County, then for Westmoreland County when it was established in 1773. Beginning in 1776, Crawford served as a surveyor and justice for Virginia's short-lived Yohogania County.[9]

American Revolution

When the American Revolutionary War began, Crawford initially was commissioned a lieutenant colonel in the 5th Virginia Regiment on February 13, 1776.[10] The 5th Virginia was raised in the counties around Richmond and originally based in Williamsburg,[11] where Crawford joined the regiment to participate in training of the recruits. Later that year, Crawford was promoted to Colonel of the 7th Virginia Regiment to fill a vacancy when Colonel William Daingerfield resigned his command of that unit.[12]

A number of histories incorrectly state that Crawford raised the 7th Virginia Regiment near Fort Pitt at the beginning of the revolution. The 7th Virginia initially was raised in southeastern Virginia near Gloucester Court House.[13] The confusion may be due to Crawford’s role in raising another regiment near Fort Pitt, the 13th Virginia, which was redesignated the 9th Virginia in 1778 and later renumbered to the 7th Virginia in 1781 while it was stationed at Fort Pitt.[14] Crawford commanded the 13th Virginia for a time in 1777.

Many histories also inaccurately state that Crawford led the 7th Virginia at the Battle of Long Island and the following retreat across New Jersey.[15] Crawford’s own words contradict this viewpoint in a letter written to George Washington from Williamsburg, VA on September 20, 1776: “I Should have com to new York with those Reget ordred their but the Regt I belong to is Ordred to this place.”[16][17] Regimental histories of the 7th Virginia[18] along with other historical references[19] also reveal that the 7th Virginia did not participate in the battle of Long Island. Similar uncertainty surrounds narratives that state Crawford was with Washington at the crossing of the Delaware and the Battles of Trenton and Princeton. Contemporary historians have sought to correct these inaccuracies, such as H. Ward in his biography of Revolutionary soldiers from Virginia: “It is disputed whether Crawford served in any part of the New York-New Jersey campaigns of 1776-1777…”[20]

Crawford apparently left the command of the 7th Virginia in November 1776. A farewell letter to Crawford from the officers of the 7th Virginia was published in the Virginia Gazette newspaper on November 22, 1776. He responded with a letter of his own in the same edition of the Gazette, bidding farewell to the 7th Virginia.[21]

He returned to his home on the frontier late in 1776 and was actively engaged in raising the 13th Virginia Regiment,[22] [23] which was authorized by Congress in September 1776 with recruiting beginning in December 1776 in the District of West Augusta of Virginia[24] (this region was claimed by Virginia and encompassed parts of present day western Pennsylvania and West Virginia). Crawford wrote to Washington from Fredricktown Maryland on February 12, 1777, to inform him he was coming from the frontier, where the officers of the regiment already had recruited about 500 men. He was on his way to Congress to seek funding for arms and supplies and then planned to immediately return home.[25][26] The Continental Congress resolved on February 17, 1777: “That 20,000 dollars be paid to Colonel William Crawford for raising and equipping the regiment under his command, part of the Virginia new levies.”[27]

The 13th Virginia, or West Augusta regiment, was raised on the condition that it remain in the West in the event of an Indian War.[28] However, with Washington’s need for reinforcements in the East, the Continental Congress on January 8, 1777, requested the governor of Virginia to order the West Augusta regiment to join Washington in New Jersey.[29] But with increased attacks on frontier settlements by Native Americans allied with the British in early 1777, a Council of War was held at Fort Pitt on March 24, 1777, that decided the 13th Virginia should not be deployed to the East at that time.[30] [31] Crawford wrote to Congress on April 22, 1777: “Honorable Sir—Having received orders to join his Excellency General Washington in the Jerseys with the battalion now under my command, which orders I would willingly have obeyed, had not a council of war held at this place (proceedings of which were transmitted to Congress by express) resolve that I should remain here until further orders.”[32] However, command of the 13th Virginia was soon given to Colonel William Russell and on June 9, 1777, several companies of the West Augusta Regiment, numbering about 300, marched eastward under Russell to join Washington and the main army near Philadelphia.[33][34] Apparently by August 1777, Crawford also led a number of new recruits (about two hundred) eastward to join Washington.[35]

During the Philadelphia campaign, he commanded a scouting detachment as part of the light infantry corps for Washington's army.[36] The light infantry was under the command of General William Maxwell[37] and Crawford was selected to serve as one of the field officers under Maxwell. William Walker, a member of the light Infantry, described Crawford in the typical attire of a frontier rifleman: “…Colonel Crawford with his leather hunting shirt, pantaloons and Rifle…”[38] The British forces, after landing at Head of Elk, Maryland, approached Philadelphia from the south through Delaware. Washington sent a contingent, including Maxwell’s Light Infantry, to block the main road to Wilmington at a crossing of the Christiana Creek known as Cooch's Bridge. On September 3, 1777, Crawford led about 300 scouts from Maxwell’s Corps to harass the vanguard of the British forces.[39][40] The fighting was intense between Crawford’s scouts and an advanced party of Hessian jagers under the command of Captain Johann Ewald, as John Chilton of the 3rd Virginia Regiment recorded in his Diary: “3d Septr. - The enemy advanced as high as the red Lion, they were met with by our advanced party under Colo Crawford – the engagement was pretty hot. several on each side was wounded and some slain.”[41]

Crawford would continue to serve in the Light Infantry Corps at the battles of Brandywine and Germantown. On October 11, 1777, militia units from the Virginia counties of Prince William, Culpepper, Loudoun, and Berkley were formed into a brigade and placed under Crawford’s command.[42] However, as the war on the western frontier intensified late in 1777, Crawford was transferred to the Western Department of the Continental Army. On November 20, 1777, Congress requested that Washington “send Col. Wm. Crawford to Pittsburg to take command, under Brig. Gen. Hand, of the Continental troops and militia in the Western Department.”[43] He served at Fort Pitt under Generals Edward Hand and Lachlan McIntosh. Crawford was present at the Treaty of Fort Pitt in 1778, and helped to build Fort Laurens and Fort McIntosh that year. Resources were scarce on the frontier, however, and Fort Laurens was abandoned in 1779. In 1780, Crawford visited Congress to appeal for more funds for the western frontier. In 1781, he retired from military service.

Crawford Expedition

In 1782, General William Irvine persuaded Crawford to lead an expedition against enemy Indian villages along the Sandusky River. Before leaving, on May 16 he made out his will and testament.[44] His son John Crawford, his son-in-law William Harrison, and his nephew and namesake William Crawford also joined the expedition.

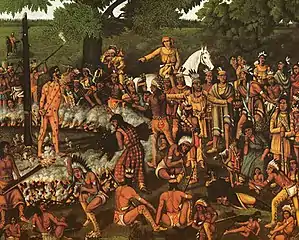

Crawford led about 500 volunteers deep into American Indian territory with the hope of surprising them. However, the Indians and their British allies at Detroit had learned about the expedition in advance, and brought about 440 men to the Sandusky to oppose the Americans. After a day of indecisive fighting, the Americans found themselves surrounded. During a confused retreat, Crawford and dozens of his men were captured. The Indians executed many of them in retaliation for the Gnadenhutten massacre earlier in the year, in which 96 peaceful Christian Indian men, women, and children had been murdered by Pennsylvanian militiamen. Crawford's execution was brutal; he was tortured for at least two hours before he was burned at the stake. His nephew and son-in-law were also captured and executed. The war ended shortly thereafter, but Crawford's horrific execution was widely publicized in the United States, worsening the already strained relationship between Native Americans and European Americans.

Legacy

In 1982, the site of Colonel Crawford's execution was added to the National Register of Historic Places. In 1877, the Pioneer Association of Wyandot County erected an 8.5 ft (2.6 m) Berea sandstone monument near the site. The Ohio Historical Society also has an historical marker nearby.

Crawford County, Ohio, Crawford County, Pennsylvania, Crawford County, Michigan, and Crawford County, Indiana, are named for William Crawford. So too is Colonel Crawford High School in North Robinson, Ohio.

There is a replica of Crawford's cabin in Connellsville, Pennsylvania.

Notes

- ↑ Thompson 2017, p. 1.

- ↑ Scholl 1995, p. 44.

- ↑ O'Donnell, "William Crawford", 710.

- ↑ Butterfield, Expedition against Sandusky, 81.

- ↑ North America, Family Histories, 1500–2000. Lineage book of the Charter Members of the Daughters of the American Revolution, pg 67.

- ↑ Crawford, David (February 27, 2016). "Crawford, David, Crawford and Other Ancestors". Crawford, David, Crawford and Other Ancestors. RootsMagic Genealogy Software. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- ↑ Butterfield, Expedition against Sandusky, 97.

- ↑ Anderson, Colonel William Crawford, 7–8.

- ↑ Butterfield, Expedition against Sandusky, 100–102.

- ↑ "Journals of the Continental Congress, Tuesday February 13, 1776, p. 132".

- ↑ Sanchez-Saavedra, E. M. (1978). Guide to Virginia military organizations in the American Revolution, 1774-1787. Richmond: Virginia State Library. p. 45. ISBN 0884900037.

- ↑ "Journals of the Continental Congress, Thursday October 10, 1776, p. 863".

- ↑ Sanchez-Saavedra. Guide to Virginia Military Organizations. p. 52.

- ↑ Sanchez-Saavedra. Guide to Virginia Military Organizations. pp. 53–54, 69.

- ↑ Butterfield, C.W. (1873). An historical account of the expedition against Sandusky under Col. William Crawford in 1782. Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co. p. 104.

- ↑ Butterfield, C. W. (1877). The Washington-Crawford letters. Being the correspondence between George Washington and William Crawford, from 1767 to 1781, concerning western lands. Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co. p. 60.

- ↑ Founders Online, National Archives. "To George Washington from Colonel William Crawford, 20 September 1776". Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ↑ The 7th Virginia Regiment. "The 7th Virginia - link to Chronological History". Retrieved August 7, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Butterfield, C. W. The Washington-Crawford letters. p. 60, note 2.

- ↑ Ward, H. M. (2011). For Virginia and For Independence, Twenty-Eight Revolutionary Soldiers from the Old Dominion. McFarland & Company. p. 152. ISBN 978-0786461301.

- ↑ The Virginia Gazette, Purdie. "Nov. 22, 1776, Page 3, column 1". Colonial Williamsburg. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ↑ Butterfield, C. W. (1882). Washington-Irvine Correspondence. Madison, Wisconsin: David Atwood. p. 116 notes.

- ↑ Thwaites, R. G. and Kellogg, L. P. (1908). The Revolution on the Upper Ohio, 1775-1777. Madison, Wisconsin: Wisconsin Historical Society. p. 250, note 94.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Sanchez-Saavedra. Guide to Virginia Military Organizations. p. 69.

- ↑ Butterfield, C. W. The Washington-Crawford letters. pp. 62–64.

- ↑ Founders Online, National Archives. "To George Washington from Colonel William Crawford, 12 February 1777". Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ↑ "Journals of the Continental Congress, Monday, February 17, 1777, p. 128".

- ↑ Thwaites, R. G. and Kellogg, L. P. The Revolution on the Upper Ohio. p. 250, note 94.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Journals of the Continental Congress, Wednesday, January 8, 1777, p. 21".

- ↑ Butterfield, C. W. The Washington-Crawford letters. p. 65, note 1.

- ↑ The Virginia Gazette, Dixon & Hunter. "Apr 18, 1776, Page 6, column 2, 'Extract of a letter from Pittsburg, dated 24 March'". Colonial Williamsburg. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ↑ Thwaites, R. G. and Kellogg, L. P. The Revolution on the Upper Ohio. pp. 249–250.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "General Edward Hand to Board of War, June 10 1777, '…The West Augusta Battalion Marched Yesterday…' Papers of the Continental Congress".

- ↑ "Colonel William Russell to Congress, undated – sometime in early 1778, '…out of three hundred men I marched down in July…,' Papers of the Continental Congress (Misc Letters to Congress, Vol 19, pg 227)".

- ↑ Butterfield, C. W. Washington-Irvine Correspondence. p. 116 notes.

- ↑ Butterfield, Expedition against Sandusky, 103–04.

- ↑ Harris, Michael C. (2017). Brandywine - A Military History of the Battle that Lost Philadelphia but Saved America, September 11, 1777. Savas Beatie. p. 124. ISBN 9781611213225.

- ↑ "Pension application of William Walker, S6340" (PDF).

- ↑ O’Callaghan, E.B. (1853). "Narrative of Sergeant William Grant" in Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York. Albany, NY: Weed, Parsons and Co. p. 733, Vol 8.

- ↑ "Life as a Secret Tory". The 8th Virginia Regiment Blog. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ↑ Cecere, M. (2009). They Behaved Like Soldiers Captain John Chilton and the Third Virginia Regiment, 1775-1778. MD: Heritage Books. p. 122. ISBN 9780788424793.

- ↑ Founders Online, National Archives. "GENERAL ORDERS, 11 October 1777, Head Quarters, Towamensing".

- ↑ "Journals of the Continental Congress, Thursday November 20, 1776, p. 944".

- ↑ Anderson, Colonel William Crawford, 17.

References

- Anderson, James H. Colonel William Crawford. Columbus: Ohio Archæological and Historical Publications, 1898. Originally published in Ohio Archæological and Historical Quarterly 6:1–34. Address delivered at the site of the Crawford monument on May 6, 1896.

- Boatner, Mark Mayo, III. Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. New York: McKay, 1966; revised 1974. ISBN 0-8117-0578-1.

- Butterfield, Consul Willshire. An Historical Account of the Expedition against Sandusky under Col. William Crawford in 1782. Cincinnati: Clarke, 1873.

- Emahiser, Grace U. From river Clyde to Tymochtee and Col. William Crawford. Commercial Press, 1969.

- Miller, Sarah E. "William Crawford". The Encyclopedia of the American Revolutionary War: A Political, Social, and Military History. 1:311–13. Gregory Fremont-Barnes and Richard Alan Ryerson, eds. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2006. ISBN 1-85109-408-3.

- O'Donnell, James H., III. "William Crawford". American National Biography. 5:710–11. Ed. John A. Garraty and Mark C. Carnes. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-19-512784-6.

- Scholl, A.W. (1995). The Brothers Crawford: Colonel William, 1722–1782 and Valentine Jr., 1724–1777. Heritage Books.

- Thompson, Robert N. (2017). Disaster on the Sandusky: The Life of Colonel William Crawford. American History Press.

- 'Colonel Crawford Burn Site Monument' Rural Crawford Township, Wyandot County, Ohio NRHP Nomination form #82003667

External links

- Historical marker in Pennsylvania, near the site where Crawford had a cabin along the Youghiogheny River.

- William Crawford at Find a Grave

- William Crawford Portrait :: Ohio Memory Collection

- National Register Nomination form PDF