| Columbia Slough | |

|---|---|

Columbia Slough near mouth | |

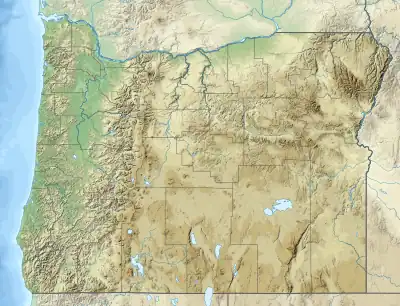

Columbia Slough watershed | |

Location of the mouth of Columbia Slough in Oregon | |

| Etymology | Columbia River |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Oregon |

| County | Multnomah |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Fairview Lake (nominal) |

| • location | Fairview, Multnomah County, Oregon |

| • coordinates | 45°33′00″N 122°27′24″W / 45.55000°N 122.45667°W[1] |

| • elevation | 10 ft (3.0 m)[2] |

| Mouth | Willamette River |

• location | Portland, Multnomah County, Oregon |

• coordinates | 45°38′36″N 122°46′07″W / 45.64333°N 122.76861°W[1] |

• elevation | 9 ft (2.7 m)[1] |

| Length | 19 mi (31 km)[3] |

| Basin size | 51 sq mi (130 km2)[3] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Portland, 0.6 miles (1.0 km) from mouth[4] |

| • average | 93.8 cu ft/s (2.66 m3/s)[4] |

| • minimum | −6,700 cu ft/s (−190 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 2,400 cu ft/s (68 m3/s) |

The Columbia Slough is a narrow waterway, about 19 miles (31 km) long, in the floodplain of the Columbia River in the U.S. state of Oregon. From its source in the Portland suburb of Fairview, the Columbia Slough meanders west through Gresham and Portland to the Willamette River, about 1 mile (1.6 km) from the Willamette's confluence with the Columbia.[5] It is a remnant of the historic wetlands between the mouths of the Sandy River to the east and the Willamette River to the west. Levees surround much of the main slough as well as many side sloughs, detached sloughs, and nearby lakes. Drainage district employees control water flows with pumps and floodgates. Tidal fluctuations cause reverse flow on the lower slough.

The Columbia floodplain, formed by geologic processes including lava flows, volcanic eruptions, and the Missoula Floods, is part of the Portland Basin, which extends across the Columbia River from Multnomah County, Oregon, into Clark County, Washington. Five percent of Oregon's population, about 158,000 people, live in the slough watershed of about 51 square miles (130 km2). Municipal wells near the upper slough provide supplemental drinking water to Portland and nearby cities. The cities, the drainage districts, the county, and a regional government, Metro, have overlapping jurisdictions in the watershed. A regional agency operates Portland International Airport along the middle slough and marine terminals near the lower slough. The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) and the city's Bureau of Environmental Services (BES) deal with environmental issues.

Long before non-indigenous people explored the region, tribes of Native Americans fished and hunted along the slough. In the early 19th century fur trappers and explorers including Lewis and Clark visited the area before large migrations of settlers began arriving from the east. The newcomers farmed, cut timber, built houses, and by the early 20th century established cities, shipping ports, roads, rail lines and industries near the slough. Increased investment in the floodplain led to larger losses during floods, and these losses prompted levee building that greatly altered the area. A flood pouring through a levee break in 1948 destroyed the city of Vanport, which was never rebuilt.

Used as a waste repository during the first half of the 20th century and cut off from the Columbia River by levees, the slough became one of Oregon's most polluted waterways. Early attempts to mitigate the pollution, which included raw sewage and industrial waste, were unsuccessful. However, in 1952 Portland began sewage treatment, and over the next six decades the federal Clean Water Act and similar legislation mandated further cleanup. State and local governments, often assisted by community volunteers, undertook projects related to public health, natural resources, and recreation in a region with many homes, industries, businesses, and roads. The businesses and industries in the watershed employ about 57,000 people, which is also frequented by more than 150 bird species and 26 fish species and animals including otters, beaver, and coyotes. One of the nation's largest freshwater urban wetlands, Smith and Bybee Wetlands Natural Area, shares the lower slough watershed with a sewage treatment plant, marine terminals, a golf course, and a car racetrack. Watercraft able to portage over culverts and levees can travel the entire length of the slough. The 40-Mile Loop and other hiking and biking trails follow the waterways and connect the parks.

Name

Slough usually rhymes with shoe in the U.S. except in New England, where it usually rhymes with now, the preferred British pronunciation.[6] Slough may mean a place of deep mud or mire, a swamp, a river inlet or backwater, or a creek in a marsh or tide flat.[6] The Columbia Slough is classified as a "stream" in the Geographic Names Information System (GNIS) of the United States Geological Survey (USGS).[1] The slough takes its name from the Columbia River, of which it was historically a side channel or anabranch. Robert Gray, a Boston fur trader and whaler who sailed partway up the Columbia River in 1792, named the river after his ship, Columbia Rediviva.[7] The Columbia part of the ship's name belonged to the tradition of naming things after explorer Christopher Columbus.[7]

Course

The Columbia Slough flows roughly parallel to and about 0.4 to 1.7 miles (0.6 to 2.7 km) south of the Columbia River in Multnomah County.[8] It begins at Fairview Lake in the city of Fairview and immediately enters the city of Gresham. Less than 1 mile (1.6 km) later, it enters the city of Portland and continues generally westward for about another 18 miles (29 km) to its confluence with the Willamette River.[8] Throughout its course, the slough is nearly level, 10 feet (3.0 m) above sea level at the source and 9 feet (2.7 m) at the mouth.[1][2] Semidiurnal tides cause reverse currents on the lower 8.5 miles (13.7 km) of the slough.[9]

Running slightly north of and parallel to U.S. Route 30 (Sandy Boulevard), the slough flows by Zimmerman Heritage Farm on the left bank (south) about 17.5 miles (28.2 km) from the mouth, Big Four Corners Wetlands on the right bank shortly thereafter, and receives Wilkes Creek on the left shortly after that. At about river mile (RM) 15.5 or river kilometer (RK) 24.9, it passes through a gated levee that separates the upper slough from the middle slough. Soon it passes Prison Pond Wetlands near Inverness Jail and connects to Johnson Lake Slough, all on the left. Shortly thereafter, it flows under Interstate 205. From here and for most of the rest of its course, the slough runs parallel to and slightly north of Columbia Boulevard. Passing Johnson Lake on the left, it crosses the Colwood National Golf Course and flows by Portland International Airport and an Oregon Air National Guard base on the right. On the left is Whitaker Ponds Natural Area. Shortly thereafter, it receives Whitaker Slough on the left and crosses the Broadmoor Golf Course. Between 9 and 8 miles (14 and 13 km) from the mouth, it receives Buffalo Slough from the left and passes by the defunct Peninsula Drainage Canal (City Canal), which lies to the slough's right. At this point, it passes through a second gated levee that separates the middle slough from the lower slough and its tidal flow reversals.[9][10]

In the next stretch, the Columbia Slough flows by Portland Meadows horse racing track on the right and crosses under Interstate 5 at about RM 7 (RK 11). Beyond the interstate, to the slough's north lies Delta Park, Portland International Raceway, and the Heron Lakes Golf Course. Until flooding destroyed it in 1948, the city of Vanport occupied this site. To the south is the Columbia Boulevard Wastewater Treatment Plant.[9][10]

The slough flows through the Wapato Wetland and by the Smith and Bybee Wetlands Natural Area, including the former St. Johns Landfill, on the right at about RM 3 (RK 4.8) from the Willamette River, and by Pier Park on the left. Shortly thereafter, it turns sharply north for the rest of its course. It receives North Slough, connected to Bybee Lake, on the right, and passes through the Ramsey Lake Wetlands and Kelley Point Park before entering the Willamette River about 1 mile (1.6 km) from its confluence with the Columbia River. The mouth of the Columbia River is about 101 miles (163 km) further downstream at Astoria on the Pacific Ocean.[5][9][10]

Discharge

Since 1989, the USGS has monitored the flow of the Columbia Slough at a stream gauge 0.6 miles (1.0 km) from the mouth.[4] The average flow recorded at this gauge is 93.8 cubic feet per second (3 m3/s) from a drainage area of undetermined size.[4] The maximum flow was 2,400 cubic feet per second (68 m3/s) on December 5, 1995, and the minimum flow (biggest reverse flow) was −6,700 cubic feet per second (−190 m3/s) on February 7, 1996, which coincided with a flood on the Columbia and Willamette rivers.[4][11][n 1][n 2][n 3]

Watershed

Draining about 51 square miles (130 km2), the Columbia Slough watershed lies in the floodplain of the Columbia River between the mouths of the Sandy River to the east and the Willamette River.[13] Parts of Portland, Fairview, Gresham, Maywood Park, Wood Village, and unincorporated Multnomah County lie within the drainage basin (watershed).[13] As of 2005, about 158,000 people, 5 percent of Oregon's population, lived in the basin.[3]

The watershed includes residential neighborhoods, agriculture, the airport, open spaces, 54 schools, interstate highways, railways, commercial businesses, and heavy and light industry.[17] In general, the northern part is industrial and commercial; the southern part is residential, and agricultural areas lie to the east.[17] As of 2001, single-family residential zones covered 33 percent of the watershed, and mixed-use zones accounted for another 33 percent.[17] The other zones were 12 percent industrial, 12 percent parks or open space; 6 percent multi-family residential, 3 percent commercial, and 2 percent were for farming or forests.[17] As of 2005, about 3,900 businesses operated in the watershed and employed about 57,000 people.[17]

Adjacent to the Columbia Slough basin are the watersheds of the Sandy River to the east, Johnson Creek to the south, the Willamette to the south and west, and the Columbia to the north. Lying slightly north of the watershed, large islands in the Columbia River include, from east to west, McGuire Island, Government Island, Lemon Island, and Tomahawk Island, which is connected to Hayden Island. Bordered by the Columbia and two arms of the Willamette, Sauvie Island lies just west of the mouth of the slough.[18][19]

Jurisdiction

Many governmental entities share responsibility for the slough and its drainage basin. Decisions by the municipal governments of Portland, Fairview, Gresham, Maywood Park, and Wood Village, and the government of Multnomah County affect the slough.[13] Metro, the regional governmental agency for the Oregon portion of the Portland metropolitan area, is involved in acquiring and protecting wildlife habitat in places like Big Four Corners Wetlands and Smith and Bybee Wetlands Natural Area, acquiring property to close gaps in the 40-Mile Loop and other trails, and creating additional water access along the slough.[20] The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has designated the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) to regulate the slough under provisions of the federal Clean Water Act.[21] The Port of Portland, a regional agency run by commissioners appointed by the Oregon governor, owns and manages about 11 percent of the land in the slough watershed.[22] Three drainage districts that manage water flows in the slough floodplain overlap parts of these other jurisdictions.[21]

Annual report card

In 2015, Portland's Bureau of Environmental Services (BES) began issuing annual "report cards" for watersheds or fractions thereof that lie within the city.[23][24] BES assigns grades for each of four categories: hydrology, water quality, habitat, and fish and wildlife. Hydrology grades depend on the amount of pavement and other impervious surfaces in the watershed and to what degree its streams flow freely, not dammed or diverted. Water-quality grades are based on measurements of dissolved oxygen, E-coli bacteria, temperature, suspended solids, and substances such as mercury and phosphorus. Habitat ranking depends on the condition of stream banks and floodplains, riparian zones, tree canopies, and other variables. The fish and wildlife assessment includes birds, fish, and macroinvertebrates.[25] In 2015, the BES grades for the Columbia Slough are hydrology, B− ; water quality, B− ; habitat, D− , and fish and wildlife, F.[26]

Geology

The Columbia Slough is part of the roughly 770-square-mile (2,000 km2) Portland Basin, which lies at the northern end of the Willamette Valley of Oregon and extends north into Clark County in the state of Washington.[27] The region is underlain by solidified lavas of the Columbia River Basalt Group that are up to 16 million years old.[28] Covered by later alluvial deposits, the basalts lie more than 1,000 feet (300 m) below the surface within the basin.[29] About 10 million years ago, eruptions of Cascade Range volcanoes to the east sent flows of mud, ash, and eroded volcanic debris into the Columbia, which was powerful enough to carry the material downstream.[30] Deposited above the basalt during the Miocene and early Pliocene, these loose sands and gravels formed part of what is known as the Troutdale Formation. Extending to the Tualatin River Valley to the south and into Clark County on the north, the formation is an aquifer that is the primary source of drinking water for Vancouver in Washington and an auxiliary source for Portland.[30]

The Portland Basin is being pulled slowly apart between faults in the Tualatin Mountains (West Hills) on the west side of Portland, the East Bank fault along the east side of the Willamette River, and other fault systems near Gresham further east. About 3 million years ago, many small volcanoes and cinder cones erupted through the thin, stretched crust of the basin and in the Cascade foothills to the southeast. Ash, cinders, and debris from these Boring Lava Field volcanoes added another layer of sediment to the Troutdale formation.[31]

About 15,000 years ago, cataclysmic ice age events known as the Missoula Floods or Bretz Floods originating in the Clark Fork region of northern Idaho inundated the Columbia River basin many times. These floods deposited huge amounts of debris and sediment. Water filled the entire Columbia Gorge to overflowing and turned the Willamette Valley into a lake 100 miles (160 km) long, 60 miles (100 km) wide and 300 feet (90 m) deep. The floodwaters ripped the face off Rocky Butte in Portland and deposited a 5-mile (8 km) gravel bar, Alameda Ridge, that runs parallel to and slightly south of the Columbia Slough.[32]

Faults associated with the expanding Portland Basin are capable of producing significant earthquakes. More than a thousand earthquakes, many too small to be felt, have been recorded in the basin since 1841. The stronger ones reached about magnitude 5 on the Richter scale. In 1892, one estimated at magnitude 5 shook downtown Portland for about 30 seconds. In 1962, one centered about 7 miles (11 km) north of Portland was estimated at between magnitude 4.9 and 5.2.[33]

Hydrology

Rainfall and runoff

Based on records from 1961 to 1990, the watershed's average annual precipitation, as measured at Portland International Airport, is about 36 inches (910 mm).[34] About 21 inches (530 mm) falls from November through February and only about 4 inches (100 mm) from June through September.[34] Since temperatures are normally below freezing fewer than 30 days a year,[35] most of this precipitation reaches the ground as rain.

Historically, most rain falling on the watershed was taken up by vegetation, flowed into wetlands, soaked into the ground, or evaporated. Heavy rain in the winter months recharged the groundwater and provided baseflows to the slough during dry summers. Urban development, which replaced vegetation and water-absorbing soils with airport runways, house roofs, highways, warehouses, parking lots, and other hard surfaces, interrupted this cycle. In 1999, a study estimated that impervious surfaces covered 54 percent of the watershed. Storm runoff that might have taken days to reach the historic slough reaches the developed slough in hours.[35]

Main channel

Until the 20th century, the slough and its side channels and associated ponds and lakes were part of the active Columbia River floodplain. When the historic river was high, the slough received water from it near Big Four Corners, about 17 miles (27 km) from the slough's mouth.[36] In 1917, landowners formed three drainage districts—Peninsula Drainage District No. 1 (Pen 1), Peninsula Drainage District No. 2 (Pen 2), and Multnomah County Drainage District No. 1 (MCDD)—to control flooding.[36] A fourth district, the Sandy Drainage Improvement Company (SDIC), manages water flow at the upper end of the slough's basin in Fairview and Troutdale.[37] By 2008, the districts maintained 30 miles (48 km) of levees as well as water pumps, floodgates and other water control devices.[13]

The upper slough extends from the slough's source at Fairview Lake, roughly 18.5 miles (30 km) from the mouth, to a gated levee known as the mid-dike levee about 3 miles (5 km) downstream. This sector, managed by MCDD, covers 2,650 acres (1,070 ha) completely surrounded by levees. A northern side channel extends from the mid-dike levee to MCDD Pump Station No. 4 on the Columbia River (Marine Drive) levee near Big Four Corners. Water usually exits this sector through the open gates of the mid-dike levee, but to control threatening flows the MCDD can close the gate and pump water from the northern side channel directly into the Columbia. The pump's maximum capacity is 275,000 U.S. gallons per minute (17,300 L/s).[38]

The middle slough, also managed by MCDD, lies between the mid-dike levee and the Pen 2 levee, 8.5 miles (13.7 km) from the mouth. This sector covers 6,848 acres (2,771 ha), is completely surrounded by levees, and contains many side sloughs, ponds, small lakes, and springs. Pump Station No. 1 rests on the Pen 2 levee, which is gated across the course of the slough. To control flows, MCDD can open or close the gates, and it can pump water from the middle slough to the lower slough when its flow is reversed by the tide or when gravity flow is insufficient. The pump's capacity is 250,000 US gallons per minute (16 m3/s).[38]

Water levels in the lower slough, managed by Pen 2 and Pen 1, depend more on Willamette River conditions than on pumping by MCDD. Incoming tides cause a variation in water surface elevation of between 12 inches (30 cm) and 24 inches (61 cm) roughly twice per day along the entire lower slough. Flow direction varies with the tide. Pen 2 and Pen 1, separated by Interstate 5, border the north side of the lower slough. Pen 2 manages 1,475 acres (597 ha) east of the highway, and Pen 1 manages 901 acres (365 ha) to the west (downstream). Multiple pump stations move water from lesser sloughs in both districts into the main slough. Parts of this subwatershed are unprotected by levees and are vulnerable to 100-year floods.[38]

Creeks and lakes

Historically Fairview Creek flowed north into the Columbia River through a wetlands slightly upstream of Big Four Corners. In the early 20th century, water managers dug an artificial channel connecting the Fairview Creek wetlands to the slough. In 1960, they built a dam on the west side of the wetlands to create Fairview Lake for water storage and recreation. It covers about 100 acres (40 ha) and is 5 to 6 feet (1.5 to 1.8 m) deep. Fairview Creek forms in a wetland near Grant Butte and flows north for 5 miles (8 km) through the cities of Gresham and Fairview to reach the lake. Fairview Creek has two named tributaries, No Name Creek, and Clear Creek. A smaller stream, Osborn Creek, also flows into the lake, which empties through a weir and culvert system into the upper slough.[38]

With one exception, the streams feeding Fairview Lake are the watershed's only remaining creeks, although springs also reach the surface.[39] Wilkes Creek, the slough's only free flowing tributary, is about 2 miles (3 km) long and enters the upper slough from the south.[38] Dozens of similar streams that once flowed into the slough from the south have all been piped or filled.[39] Many bodies of water in addition to the main slough channel lie within the drainage basin. The area around the middle slough contains several slough arms and small lakes, including Buffalo Slough, Whitaker Slough, Johnson Lake, Whitaker Ponds, and Prison Pond.[38] In the lower slough, Smith and Bybee Wetlands Natural Area at 2,000 acres (810 ha) is one of the largest urban freshwater wetlands in the United States.[40] A 1-mile (1.6 km) side slough called North Slough connects Bybee Lake and the main slough channel.[38] A water control structure at the outlet from Bybee Lake to the North Slough regulates the lakes' levels.[38]

Aquifers and wells

Groundwater discharges from an aquifer near the surface supply an estimated flow between 50 and 100 cubic feet per second (1.4 and 2.8 m3/s) to the middle and upper sloughs. Rain infiltration and artificial sumps recharge this shallow aquifer. Geologists have identified four other major aquifers separated by relatively impermeable clays or other strata at various levels below the surface aquifer. The City of Portland's water bureau manages the Columbia South Shore Well Field that taps the deeper aquifers. As of 2004, 25 active wells drawing from depths ranging from 60 to 600 feet (18 to 183 m) could produce up to 100 million US gallons (380,000 m3) a day from the field. These were drilled between 1976 and 2003 to supplement the city's main water supply from the Bull Run Watershed during droughts or emergencies. The Rockwood Water People's Utility District (PUD) and the City of Fairview have also drilled three wells near the upper slough.[41]

History

Early inhabitants

Archeological evidence suggests that Native Americans lived along the lower Columbia River as early as 10,000 years ago, including near what later became The Dalles, on the Columbia River about 70 miles (110 km) east of the Columbia Slough.[42] By 2,000 to 3,000 years ago, the Clackamas Indians had settled along the Clackamas River, which empties into the Willamette River about 25 miles (40 km) south of the slough.[43] The Clackamas tribe was a subgroup of the Chinookan speakers who lived in the Columbia River Valley from Celilo Falls to the Pacific Ocean. Clackamas lands included the lower Willamette River from Willamette Falls, at what later became Oregon City, to the Willamette's confluence with the Columbia River.[43] The Columbia River floodplain near the mouth of the Willamette contained many stream channels, lakes, and wetlands that flooded annually. Chinookan tribes hunted and fished there and traveled between the two big rivers via the protected waters of the slough.[44] Their main food sources were salmon, sturgeon, and camas.[44]

In 1792, Lieutenant William Broughton, a British explorer, led the first trip by non-natives as far up the Columbia River as the mouth of the Sandy River. He and his men camped on Sauvie Island, which lies between the Willamette and Columbia rivers directly opposite the mouth of the slough. Broughton encountered many Chinookans while exploring and mapping geographic features including Hayden Island and other islands in the Columbia just north of the slough.[45] When Lewis and Clark visited the area in 1806, the Clackamas tribe consisted of about 1,800 people living in 11 villages.[43] The explorers estimated that 800 people of the Multnomah tribe of Chinookans lived in five villages on Sauvie Island.[46]

In 1825, the Hudson's Bay Company established its western administrative headquarters at Fort Vancouver, across the Columbia River from the slough. The British fort became the center for fur trading and other commerce throughout the Pacific Northwest, including what would later become the state of Oregon.[47] By the 1830s, smallpox, malaria, measles and other diseases carried by non-indigenous explorers and traders had reduced the native population by up to 90 percent throughout the lower Columbia basin.[48] The United States gained control over the Oregon Territory—including Fort Vancouver, the Portland Basin, and the slough—by treaty with Great Britain in 1846.[49] By 1851, the Clackamas tribe's population had fallen to 88, and in 1855 the tribe signed a treaty surrendering its lands to the U.S.[43]

Farming, commerce, and industry

By 1850, White settlers established donation land claims in the Columbia Slough watershed. One settler, Lewis Love, became wealthy by cutting timber in the watershed and using the slough as part of a shipping route to downtown Portland.[44] Other settlers logged the forests near the slough and built sawmills, fished, and farmed. In 1852, James John operated a ferry based on the peninsula of land between the Columbia and the Willamette River. The community of St. Johns, platted in the same year on the peninsula, is named after him.[51] Legislation creating the Port of Portland in 1891 improved St. Johns' prospects as a Willamette River port.[44] In 1902, the U.S. Congress passed a Reclamation Act that encouraged irrigation, flood control, and wetland development in places like the peninsula.[44] In 1907, the Spokane, Portland and Seattle Railway began work on a rail line across the peninsula.[44] The railway and the port improvements led to high expectations. "St. Johns, the City of Destiny", a 1909 editorial appearing in a booster publication called The Peninsula, said:

Nature has been more than lavish in her gifts to St. Johns. Travel as many miles as you like and go where you will, it is highly improbable that you will find a spot with so many magnificent nature advantages as has St. Johns. The fine stretch of level land on which the city is located, the deep water of the two rivers, the navigable sloughs and the superb scenery which nature has painted with a master hand, makes the location an ideal one in every respect either for industries or residences.[52]

Open sewer

As Portland grew, it annexed St. Johns and expanded into the peninsula and other parts of the watershed. East of St. Johns, the Swift Meatpacking Company bought 3,400 acres (1,400 ha) in 1906 and established the community of Kenton. Other companies built packing plants and slaughterhouses along the slough, and by 1911 Portland had become the main livestock market for the Pacific Northwest.[53] These and other early 20th century businesses, including stockyards, a dairy farm, a shingle company, and a lumber mill, flushed waste products into the slough.[54] Starting in 1910, north Portland's residential sewage also poured into the slough through pipes laid for the purpose.[44] In 1917, landowners along the slough had formed three drainage districts to control floods. They dug ditches, deepened existing water channels, and built levees to keep the rivers and the slough from flooding agricultural, industrial, and commercial property. Hoping to flush the slough with clean water from the river, city engineers created the crosscutting Peninsula Canal. The project largely failed because daily tides reversed the slough's flow and because both ends of the canal were at nearly the same elevation.[44]

Over the next 30 years, more lumber and wood products companies opened along the slough, and tugboats moved log rafts up and down the waterway. Truck freight and other transportation companies built in the watershed. The city created the St. Johns Landfill on wetlands and small channels off the lower slough and built a new Portland Airport on land along the middle slough. Activists and civic leaders, concerned about pollution on the Willamette River, led cleanup campaigns, but voters declined to pay for sewage treatment. Pollution eventually grew so bad on the slough that mill workers refused to handle logs that had been stored in its water.[44]

World War II and after

After the start of the war with Japan, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an order for internment of all the people of Japanese ancestry who lived on the West Coast. About 1,700 of them lived in Portland, and some had farms or businesses near the slough. When the government removed them from their homes in 1942, it housed them temporarily in the Livestock Exposition Center (Expo Center) in Kenton before sending them to internment camps further inland. They were not allowed to return until 1945.[55]

In 1942, Kaiser Shipbuilding Company began making ships for the war at three huge installations near the lower slough, one in St. Johns, one on Swan Island in Portland's Overlook neighborhood, and one in Vancouver, Washington.[56] St. Johns and Vancouver made Liberty ships, while Swan Island made tankers.[56] The St. Johns shipyard became the nation's leading producer of Liberty ships.[56] To house shipyard workers and their families, Henry J. Kaiser bought 650 acres (260 ha) of former marsh, pasture, and farmland in the lower slough watershed surrounded on all sides by dikes between 15 and 25 feet (5 and 8 m) high.[54] Here he built a new city, at first called Kaiserville and later Vanport. By 1943, Vanport's population of 39,000 made it the second largest city in Oregon and the largest wartime housing project in the U.S.[54] After the war, the population fell to about 18,500.[54] This was roughly the number of people living there on May 30, 1948, when a flood broke through Vanport's western levee.[54] The break occurred during the afternoon of a day with mild weather.[57] The first rush of water soon became a "creeping inundation",[57] slowed in its advance for 35 to 40 minutes by water-absorbing sloughs.[57] The water's gradual rise within the city allowed most of the residents to escape drowning. The county coroner's official list of bodies recovered was set at fifteen, and seven people on a list of missing people were never found.[58] The flood destroyed the city, which was never rebuilt.[54]

The Vanport flood induced changes to the slough's system of levees, which were rebuilt and in some cases fortified to withstand a 100-year flood. Instead of repairing the levee along the Peninsula Canal, the city plugged it at both ends. The disaster also affected Oregon's system of higher education. After floodwaters destroyed the Vanport Extension Center, set up in 1946, the Oregon Board of Higher Education reestablished the school in downtown Portland, where it eventually became Portland State University.[44]

Debate about how to use the slough and its watershed continued through the rest of the century. In 1964, the Port of Portland, interested in industrial development, began to fill Smith, Bybee, and Ramsey lakes with dredge sands from the Columbia.[44] In the 1970s, the Oregon Legislature passed a law against filling Smith or Bybee lakes below a contour line 11 feet (3.4 m) above mean sea level except to enhance fish and wildlife habitat.[44] Plans for a Willamette River Greenway project proposed by Oregon Governor Tom McCall in the late 1960s called for park and recreation areas along the Willamette and many of its tributaries but ignored the slough.[54] Some planners argued that the slough was so filthy that more industry was all it was good for. They portrayed cleanup as a lofty but impractical goal.[54]

At Oregon's request, the U.S. Congress stripped the slough of its navigable status in 1978.[59] This ended channel dredging on the slough, which could then be used for recreation.[59] Other laws affecting the slough in the 1970s and beyond were the federal Clean Water Act and the Oregon Comprehensive Land Use Planning Act.[44] In 1986, a business association began promoting commercial development along the upper slough, and the city later used urban renewal funds to support industrial projects near the airport.[44] In 1996 the city acquired the Whitaker Ponds Natural Area, where it began a slough watershed education program for children.[44]

Pollution

After years of piping raw sewage directly into the waterway, Portland built its first sewage treatment plant next to the lower slough in 1952. The Columbia Boulevard Wastewater Treatment Plant handled a combination of raw sewage and storm runoff that flowed into the sanitary sewer system from all over the city and piped the treated water into the Columbia River. When runoff exceeded the plant's capacity during heavy rains, sewage still entered the slough from combined sewer overflows (CSO)s at 13 outfalls.[44]

The city closed the St. Johns Landfill, adjacent to the lower slough, in 1991. Pressed by citizen action groups, it agreed in 1993 to establish a 50-foot (15 m) environmental conservation zone along the slough. In response to a threatened lawsuit, the city began a comprehensive cleanup of the slough in 1994, and a year later it received a $10 million grant from the EPA for the purpose.[44]

Of the streams monitored in the lower Willamette basin by the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) between 1986 and 1995, the Columbia Slough had the worst pollution scores. DEQ's measurements came from the slough at Landfill Road, 2.6 miles (4.2 km) from the mouth. On the Oregon Water Quality Index (OWQI) used by DEQ, water quality scores can vary from 10 (worst) to 100 (ideal). The average for the Columbia Slough was 22, or "very poor". By comparison, the average in the Willamette River at the Hawthorne Bridge in downtown Portland was 74 during the same years. Measurements of water quality at the Landfill Road site during the years covered by the DEQ report showed high concentrations of phosphates, ammonia and nitrates, fecal coliform bacteria, and suspended solids, and a high biochemical oxygen demand. High temperatures enhanced extreme eutrophication in the summer.[60]

The Port of Portland began efforts in 1997 to reduce the flow of aircraft deicing chemicals from the airport into the waterway,[44] though it still diverted concentrated chemicals (mostly glycol) directly into the slough during rare times of reservoir overflow.[61] By 2012, the Port had completed work on an enhanced system that collects, stores, and treats the chemicals, and is more likely to direct runoff to the Columbia River than the slough.[62]

By 2000 the City of Portland had spent about $200 million to nearly eliminate CSOs from entering the slough.[44] It also replaced septic tank and cesspool systems near the middle and upper slough with sanitary sewers.[44] BES analysis of water samples taken between 1995 and 2002 showed that by the end of this period DEQ water quality standards for Escherichia coli, the indicator organism for fecal contamination, were nearly always being met in the upper and middle sloughs and generally being met in the lower slough.[63] Despite these and other improvements in water quality, the slough is not a safe source of edible fish. The Multnomah County Health Department and other agencies have advised people to avoid or greatly reduce consumption of fish and crayfish from the slough because they contain polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB) and pesticides.[64]

Biology

Habitat

Development since 1850 has greatly altered the places in the watershed where plants and animals can thrive. In a report published in 2005, the Portland Bureau of Environmental Services (BES), using data from an early United States General Land Office survey, compared the watershed of 1851 with that of 2003. The study showed that all of the watershed provided plant and wildlife habitat in 1851, but by 2003 only 33 percent provided habitat. In 1851, water covered 10 percent of the watershed but that had been cut in half by 2003. Marshes and other wetlands that had comprised 22 percent of the earlier watershed dwindled to 1 percent by 2003, while the percentage of land devoted to industry, commerce, and homes rose from 0 to 34. In addition, habitat remaining in 2003 was greatly disturbed, dominated by Himalayan blackberry and other invasive species and fragmented by roads. The riparian zone along the slough was generally narrow or nonexistent and devoid of trees and shrubs in places, including along the levees.[65]

In 2002 the city, the MCDD, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began a project to improve habitat by creating 7 miles (11 km) of stream meanders and wetland terraces along the slough.[66] Through its Watershed Revegetation Program, begun in 1996, the city worked with property owners to plant native vegetation and to remove invasive weeds. Through 2005, participants had replanted more than 500 acres (200 ha) along nearly 40 miles (64 km) of riparian corridors in the slough watershed.[67] Other strategies pursued by the city, Metro, and other interest groups include connecting separated habitats with a continuous riparian corridor, removing wildlife corridor barriers, restoring hydrological connections to the slough, and restoring the floodplain where feasible.[68]

Fish and wildlife

Although reduced and altered, habitats in the watershed support a wide range of wildlife, some of which is found nowhere else in Portland.[65] Many species that used the slough in 1850 still use it. This includes more than 150 species of birds, 26 species of fish of which 12 species are native[69] several kinds of amphibians, western pond turtles, beaver, muskrat, river otter, and black-tailed deer.[65] Juvenile salmon enter the lower slough as well as Smith and Bybee Lakes.[70] Coastal cutthroat trout inhabit Fairview Creek and Osborn Creek.[70] Three species of native freshwater mussel live in the slough and in Smith and Bybee Lakes.[71] Crayfish have been found throughout the slough.[72] Bald eagles are among the resident birds, and great blue herons have established rookeries in the watershed.[65] Migrants that visit the slough include more than a dozen species of ducks, geese, swans, and raptors, as well as Neotropical shorebirds and songbirds.[65] Invasive species adapted to the slough include the nutria, common carp, bullfrog, and European starling.[65]

Vegetation

The slough watershed lies in the Portland/Vancouver Basin ecoregion, part of the Willamette Valley ecoregion designated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).[73] Black cottonwood, red osier dogwood, willow, Oregon white oak, and Oregon ash grow in scattered locations throughout the watershed, while wapato and Columbia sedge thrive in a few places.[65] In the slough itself, macrophytes and algae sometimes restrict water flow and reduce water quality.[74] Golf courses and athletic fields near the slough consist mainly of non-native grasses.[75] Developed plots with houses or businesses often have deciduous street trees, grasses, occasional conifers, and a variety of native and non-native shrubs.[75] Invasive plants include Himalayan blackberry, English ivy, reed canarygrass, purple loosestrife, and Japanese knotweed.[65]

Recreation

Public parks and wetlands

At the upper end of the slough, the City of Fairview manages Lakeshore Park, 5.2 acres (2.1 ha) on the south edge of Fairview Lake.[76] Slightly further north is Blue Lake Regional Park, a 101-acre (41 ha) recreational park with a 64-acre (26 ha) lake, both managed by Metro.[77][78] To the northeast is Chinook Landing Marine Park, also managed by Metro. At about 67 acres (27 ha), it is Oregon's largest public boating park on the Columbia River.[79]

Big Four Corners Wetlands, managed by the Portland Parks & Recreation Department (PPR), includes about 165 acres (67 ha) of wetlands and forests about 17 miles (27 km) from the slough's confluence with the Willamette River.[80] Providing habitat for deer, coyotes, and river otter as well as birds and amphibians, it is the fourth largest natural area in the city.[80] Further downstream, a consortium of interest groups is restoring a natural area of about 15 acres (6.1 ha) at Johnson Lake.[81] Whitaker Ponds Nature Park, at about RM 10 (RK 16), is a 25-acre (10 ha) site with a walking trail, canoe launch, garden, and wildflower meadow.[9][82] West of Whitaker Ponds, the Columbia Children's Arboretum, with every state tree, lies on a 29-acre (12 ha) property managed by PPR.[10][83]

Delta Park is a large municipal park complex that straddles Interstate 5 between the slough and the Columbia River at the former Vanport site. East Delta Park, covering about 85 acres (34 ha), has a sports complex and a street-tree arboretum.[84] Portland International Raceway, for car, motorcycle, and bicycle racing, occupies about 292 acres (118 ha) of West Delta Park.[85] Adjacent to the raceway is the Heron Lakes Golf Course, 340 acres (140 ha). The grounds include wetlands and interpretive signs about Vanport.[86] Smith and Bybee Wetlands Natural Area, a public park and nature reserve managed by Metro, lies just west of Delta Park. At about 2,000 acres (810 ha), it is one of the largest urban freshwater wetlands in the United States.[40][87] Kelley Point Park covers 104 acres (42 ha) at the tip of the peninsula between the Willamette and Columbia rivers.[88]

Trails

Next to Columbia River, long segments of the 40-Mile Loop skirt the north edge of the slough watershed, while other segments such as the north–south I-205 Bike Path cross it or, as in the case of the largely unfinished Columbia Slough Trail, run through it generally along an east–west axis.[89] The 40 Mile Loop is a partly completed greenway trail around and through Portland and other parts of Multnomah County. Originally proposed by the Olmsted Brothers, architects involved in the planning for Portland's Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition of 1905, it has expanded to a projected 140 miles (230 km), encircling the city and connecting parks along the Columbia, Sandy, and Willamette rivers and Johnson Creek.[90] The parks and other public spaces in the watershed have their own pedestrian paths, some of which are also bicycle paths that connect to the 40 Mile Loop. Many gaps lie between completed trail segments.[89]

Along the east side of the slough watershed, the City of Gresham has opened a 1.24-mile (2.00 km) segment of the Gresham-Fairview Trail, a planned 5.2-mile (8.4 km), north–south hiking and biking route between the Springwater Corridor along Johnson Creek and the 40 Mile Loop along the Columbia River.[91] On the west side of the watershed, the Peninsula Crossing Trail connects Willamette Cove on the Willamette River in St. Johns with the 40 Mile Loop along the Columbia River.[10] This 3-mile (4.8 km) linear hiking and biking trail crosses the lower slough and passes between Smith Lake and Heron Lakes Golf Course.[10] The trail is level and accessible by wheelchair.[10] Amenities include a picnic area, seats carved from basalt, and art installations.[10]

Boating

Accessible to canoers and kayakers of all skill levels, the slough is essentially flat. A trip from source to mouth is possible via the main channel but requires portages around levees and other obstacles. BES estimates the time required for a canoe trip of roughly 18 miles (29 km) along the main channel to be at least nine hours. Trips along the lower 8.5 miles (13.7 km) must be timed with the tides to allow paddling with the current. Eight launch sites, including one just below Fairview Lake at the headwaters and another at Kelley Point Park near the mouth, have been established along the slough.[9]

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ The National Weather Service says that when a gauge on the Columbia River at Vancouver, Washington, registers a river stage above 24 feet (7.3 m), "expect numerous sloughs to begin flooding in the Portland and Vancouver area".[12] This gauge recorded a flood crest of 27.20 feet (8.29 m) on February 9, 1996,[12] two days after the biggest recorded reverse flow on the Columbia Slough. The Vancouver gauge had recorded higher historic flood crests such as those associated with the Vanport flood of 1948,[12] but they predated the installation of the USGS gauge on the slough.

- ↑ Flows can also reverse direction during the tidal cycle, and the USGS has been filtering the tidal effect from the gauge data since 2007.[4] A levee 8.5 miles (13.7 km) from the slough's mouth prevents reverse flows from entering the middle slough.[9] Piped water, levees, and a system of pumps regulate the flows above this levee.[13]

- ↑ The tidal flows consist of fresh water rather than brackish water because saltwater intrusion up the Columbia River stops at about 23 miles (37 km) from the ocean.[14] Tides affect the Columbia River for its lower 146 miles (235 km) between the Pacific Ocean and Bonneville Dam.[15] Tides also affect the lower 26.5 miles (42.6 km) of the Willamette River, and reverse flows have been recorded as far upstream as Ross Island, 15 miles (24 km) from the mouth.[16]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Columbia Slough". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. November 28, 1980. Retrieved May 25, 2008. The mouth elevation was determined by entering the GNIS coordinates in Google Earth.

- 1 2 "Fairview Lake". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. November 28, 1980. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- 1 2 3 Bureau of Environmental Services (2008). "Columbia Slough Watershed". City of Portland. Archived from the original on August 8, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Water-Data Report 2011: USGS 14211820 Columbia Slough at Portland, OR" (PDF). United States Geological Survey (USGS). Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- 1 2 United States Geological Survey. "United States Geological Survey Topographic Map, Sauvie Island, OR quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- 1 2 "slough". Merriam-Webster Online. Retrieved December 29, 2008.

- 1 2 McArthur & McArthur 2003, pp. 220–21.

- 1 2 City Street Map: Portland, Gresham (Map) (2007 ed.). G.M. Johnson and Associates. ISBN 978-1-897152-94-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Portland Bureau of Environmental Services (2002). "A Paddler's Access Guide: Columbia Slough" (PDF). City of Portland. Archived from the original on April 29, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Houck & Cody 2000, pp. 279–319.

- ↑ "Flood Statement, Bulletin No. 47, National Weather Service, Portland, OR". University of Oregon. February 7, 1996. Archived from the original on August 8, 2015. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Columbia River at Vancouver". National Weather Service, Advanced Hydrologic Prediction Service. February 12, 2015. Archived from the original on August 8, 2015. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Portland Bureau of Environmental Services (2008). "Columbia Slough: About the Watershed". City of Portland. Archived from the original on April 29, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2008.

- ↑ "Description: Columbia River Basin, Washington". United States Geological Survey (USGS). 2002. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ↑ "Quick Facts". Lower Columbia River Estuary Partnership. Archived from the original on August 8, 2015. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ↑ "Sediment Oxygen Demand in the Lower Willamette River, Oregon, 1994" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 9, 2015. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bureau of Environmental Services 2005b, pp. 6–8, chapter 4.

- ↑ Streets of Portland (Map) (2006 ed.). Rand McNally. ISBN 0-528-86776-8.

- ↑ Vancouver, Camas/Washougal Washington (Map) (2003 ed.). Rand McNally. ISBN 0-528-99919-2.

- ↑ "Columbia Slough". Metro (Oregon regional government). 2008. Retrieved December 5, 2008.

- 1 2 Bureau of Environmental Services 2005c, p. 10, chapter 5.

- ↑ Bureau of Environmental Services 2005b, p. 10, chapter 4.

- ↑ Bureau of Environmental Services (2015). "About Watershed Report Cards". City of Portland. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- ↑ Bureau of Environmental Services (2015). "Report Cards". City of Portland. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- ↑ Bureau of Environmental Services (2015). "What We Measure". City of Portland. Archived from the original on July 28, 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- ↑ Bureau of Environmental Services (2015). "Columbia Slough Report Card". City of Portland. Archived from the original on August 9, 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- ↑ Evarts, Russell C. (2004). "Geologic Map of the Saint Helens Quadrangle, Columbia County, Oregon, and Clark and Cowlitz Counties, Washington". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on August 8, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- ↑ Bishop 2003, pp. 132–40.

- ↑ "Portland Basin". Washington State Department of Natural Resources. 2015. Archived from the original on August 9, 2015. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- 1 2 Bishop 2003, pp. 174–75.

- ↑ Bishop 2003, pp. 192–93.

- ↑ Bishop 2003, pp. 226–29.

- ↑ Bishop 2003, pp. 248–49.

- 1 2 Taylor & Hannan 1999, p. 134.

- 1 2 Bureau of Environmental Services 2005c, p. 9, chapter 5.

- 1 2 Bureau of Environmental Services 2005c, p. 2, chapter 5.

- ↑ "MCDD Flood Protection: SDIC". Multnomah County Drainage District. 2015. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bureau of Environmental Services 2005c, pp. 6–8, chapter 5.

- 1 2 Bureau of Environmental Services 2005c, p. 5, chapter 5.

- 1 2 "The Wetlands". Friends of Smith and Bybee Lakes. 2008. Archived from the original on April 17, 2003. Retrieved December 10, 2008.

- ↑ Bureau of Environmental Services 2005c, pp. 14–17, chapter 5.

- ↑ Taylor 1998, pp. 13–14.

- 1 2 3 4 Taylor 1999, pp. 11–13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Bureau of Environmental Services 2005a, pp. 1–9, chapter 3.

- ↑ Mockford, Jim (Winter 2005). "Before Lewis and Clark, Lt. Broughton's River of Names: The Columbia River Exploration of 1792". Oregon Historical Quarterly. Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Society. 106 (4): 542–67. doi:10.1353/ohq.2005.0011. JSTOR 20615586. S2CID 165732801.

- ↑ "Multnomah Indians". Lewis and Clark Interactive Journey Log. National Geographic. 2008. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- ↑ "Fort Vancouver: Frequently Asked Questions". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. 2006. Archived from the original on August 7, 2015. Retrieved October 10, 2008.

- ↑ Bureau of Planning (2001). "Guild's Lake Industrial Sanctuary Plan" (PDF). City of Portland. Archived from the original on August 5, 2015. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- ↑ "Oregon History: The "Oregon Question" and Provisional Government". Oregon Blue Book. Oregon State Archives. 2008. Retrieved October 11, 2008.

- ↑ "Zimmerman House". Parks and Recreation Division, City of Gresham. 2008. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved December 23, 2008.

- ↑ McArthur & McArthur 2003, pp. 837–38.

- ↑ "St. Johns the City of Destiny". Center for Columbia River History. Archived from the original on June 7, 2008. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ↑ "When Cattle Was King: Kenton". Center for Columbia River History. Archived from the original on November 16, 2007. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Stroud, Ellen (1999). "Troubled Waters in Ecotopia: Environmental Racism in Portland, Oregon" (PDF). Radical History Review. New York, N.Y.: MARHO. 1999 (74): 65–95. doi:10.1215/01636545-1999-74-65. ISSN 0163-6545. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 29, 2015. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ↑ "Survival on the Slough: Shikata Na Gai". Center for Columbia River History. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Maben 1987, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 Maben 1987, p. 106.

- ↑ Maben 1987, p. 122.

- 1 2 Little 1990, p. 78.

- ↑ Cude, Curtis (1995). "Laboratory and Environmental Assessment, Lower Willamette Basin". Oregon Department of Environmental Quality. Archived from the original on April 30, 2015. Retrieved December 21, 2008.

- ↑ "Airport Deicing Activities During Winter Storms". Port of Portland. December 31, 2008. Archived from the original on 2015-05-01. Retrieved January 27, 2009.

- ↑ "Current Status". Port of Portland. Archived from the original on 2015-08-08. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- ↑ Bureau of Environmental Services 2005d, pp. 3–4, chapter 6.

- ↑ Bureau of Environmental Services. "Columbia Slough Fish Advisory". City of Portland. Archived from the original on August 9, 2015. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bureau of Environmental Services 2005e, pp. 6–7, chapter 7.

- ↑ Bureau of Environmental Services 2005e, p. 21, chapter 7.

- ↑ Bureau of Environmental Services 2005e, p. 18, chapter 7.

- ↑ Bureau of Environmental Services 2005e, pp. 34–35, chapter 7.

- ↑ Bureau of Environmental Services 2005e, p. 12, chapter 7.

- 1 2 Bureau of Environmental Services 2005e, p. 9, chapter 7.

- ↑ Bureau of Environmental Services 2005e, p. 15, chapter 7.

- ↑ Bureau of Environmental Services 2005e, p. 13, chapter 7.

- ↑ Thorson, T.D.; Bryce, S.A.; Lammers, D.A.; et al. (2003). "Ecoregions of Oregon (color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photographs; downloads rather than displays)" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved November 18, 2019 – via Oregon State University.

- ↑ Bureau of Environmental Services 2005e, p. 11, chapter 7.

- 1 2 Bureau of Environmental Services 2005e, pp. 27–28, chapter 7.

- ↑ "Fairview Comprehensive Plan 2004" (PDF). City of Fairview. June 2004. p. 66. Retrieved December 7, 2009 – via University of Oregon Library Scholars Bank.

- ↑ Pfauth, Mary; Sytsma, Mark (2004). "Integrated Aquatic Vegetation Management Plan for Blue Lake, Fairview, Oregon" (PDF). Center for Lakes and Reservoirs, Portland State University. Archived from the original on August 8, 2015. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ↑ "Blue Lake Regional Park". Metro Regional Government. 2008. Archived from the original on August 7, 2015. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ↑ "Roberts, Metro Commemorate 20 Years of Chinook Landing". Metro Regional Government. 2011. Archived from the original on August 9, 2015. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- 1 2 Bureau of Environmental Services (2008). "Big Four Corners Land Acquisition" (PDF). City of Portland. Archived from the original on August 9, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2008.

- ↑ Parks and Recreation Department (2009). "Vegetation Unit Summaries for Johnson Lake Property". City of Portland. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ↑ Parks and Recreation Department (2015). "Whitaker Ponds Nature Park". City of Portland. Archived from the original on August 9, 2015. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ↑ Parks and Recreation Department (2008). "Columbia Children's Arboretum". City of Portland. Archived from the original on August 9, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2008.

- ↑ Parks and Recreation Department (2008). "Delta Park". City of Portland. Retrieved December 10, 2008.

- ↑ Parks and Recreation Department (2008). "Portland International Raceway". City of Portland. Retrieved December 10, 2008.

- ↑ Parks and Recreation Department (2008). "Heron Lakes Golf Course". City of Portland. Archived from the original on August 10, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2008.

- ↑ "Smith and Bybee Wetlands". Metro Regional Government. 2008. Archived from the original on August 8, 2015. Retrieved December 11, 2008.

- ↑ Parks and Recreation Department (2008). "Kelley Point Park". City of Portland. Archived from the original on August 10, 2015. Retrieved December 11, 2008.

- 1 2 "Main Map". 40-Mile Loop Land Trust. 2014. Archived from the original on August 9, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ↑ "History of the Loop". 40-Mile Loop Land Trust. 2004. Archived from the original on August 9, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Gresham/Fairview Trail Master Plan". City of Gresham. 2008. Archived from the original on August 7, 2015. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

Sources

- Bishop, Ellen Morris (2003). In Search of Ancient Oregon: A Geological and Natural History. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN 978-0-88192-789-4.

- Houck, Mike; Cody, M. J., eds. (2000). Wild in the City: A Guide to Portland's Natural Areas. Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87595-273-4.

- Little, Charles E. (1990). Greenways for America. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5140-7.

- Maben, Manley (1987). Vanport. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87595-118-8.

- McArthur, Lewis A.; McArthur, Lewis L. (2003) [1928]. Oregon Geographic Names (7th ed.). Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87595-277-2.

- Bureau of Environmental Services (2005a). "Columbia Slough: Current Characterization: Chapter 3: A Brief History". City of Portland. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- Bureau of Environmental Services (2005b). "Columbia Slough Watershed Current Characterization: Chapter 4: Land Use and Demographics". City of Portland. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- Bureau of Environmental Services (2005c). "Columbia Slough Watershed Current Characterization: Chapter 5: Stream Flow and Hydrology Characterization". City of Portland. Archived from the original on April 29, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- Bureau of Environmental Services (2005d). "Columbia Slough Watershed Current Characterization: Chapter 6: Water and Sediment Quality Characterization". City of Portland. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- Bureau of Environmental Services (2005e). "Columbia Slough Watershed Current Characterization: Chapter 7: Physical Habitat and Biological Communities Characterization". City of Portland. Archived from the original on October 2, 2012. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- Taylor, Barbara (1999). "Salmon and Steelhead Runs and Related Events of the Clackamas River Basin: A Historical Perspective" (PDF). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 12, 2006. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- Taylor, Barbara (1998). "Salmon and Steelhead Runs and Related Events of the Sandy River Basin – A Historical Perspective" (PDF). Portland General Electric. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 10, 2007. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- Taylor, George H.; Hannan, Chris (1999). The Climate of Oregon: From Rain Forest to Desert. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87071-468-9.

.jpg.webp)