| Sneinton | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Sneinton Dale, the area's high street | |

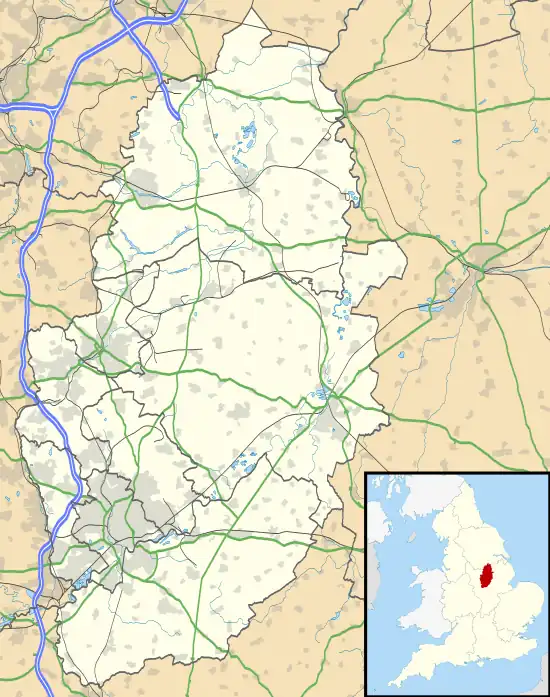

Sneinton Location within Nottinghamshire | |

| Population | 12,689 (2011)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SK 58848 39685 |

| Unitary authority | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | NOTTINGHAM |

| Postcode district | NG2 |

| Dialling code | 0115 |

| Police | Nottinghamshire |

| Fire | Nottinghamshire |

| Ambulance | East Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

Sneinton (pronounced "Snenton") is a suburb of Nottingham and former civil parish in the Nottingham district, in the ceremonial county of Nottinghamshire, England. The area is bounded by Nottingham city centre to the west, Bakersfield to the north, Colwick to the east, and the River Trent to the south. Sneinton lies within the unitary authority of Nottingham City, having been part of the borough of Nottingham since 1877.

Sneinton existed as a village since at least 1086, but remained relatively unchanged until the industrial era, when the population dramatically expanded. Further social change in the post-war period left Sneinton with a multicultural character. Sneinton residents of note include William Booth, founder of The Salvation Army, and mathematician George Green, who worked Green's Mill at the top of Belvoir Hill.

In modern times, regeneration has seen most of the old telephone exchange converted into student accommodation, the market place replaced by a pedestrian plaza and the wholesale fruit and fish market units in the traditional avenue layout re-used for artisan small businesses.[2][3][4]

History

The history of Sneinton is inextricably tied to that of its near neighbour, the City of Nottingham. When the area that is now Nottingham was settled by the Anglo-Saxon chieftain "Snot", he named the settlement "Snottingham" (the homestead of Snot's people, where inga = the people of; ham = homestead),[5] and the area east of the city, also settled by Saxons, was called "Snottington" (the suffix ton = farmstead settlement).[6] Sneinton is mentioned in the Domesday Book, where is referred to as "Notintone", which represents the Norman pronunciation of an Anglo-Saxon placename, with the "Sn" dropped in favour of "N", which was easier to say in the Norman language.[7] The Norman pronunciation of "Nottingham" stuck, whereas their pronunciation of "Notintone" did not.[6] In the years between 1086 and 1599, "Sneinton" became the agreed way of spelling the village name.[7]

In 1891 the parish had a population of 17,439.[8] On 26 March 1897 the parish was abolished and merged with Nottingham.[9]

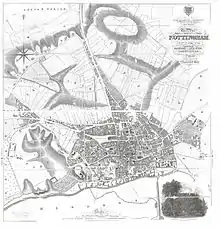

Industrial era

Until the 19th century Sneinton was no more than a village, standing on a high ridge about a mile east of Nottingham town centre overlooking the valley of the River Trent. The village was to change dramatically when the principal landowner of the time, the First Earl Manvers, sold off the land between Nottingham and Sneinton to developers. Housing was built on the land in which Nottingham's factory workers lived. Building regulations at that time were somewhat lax, and so the new landscape was to become a slum. Poverty and poor sanitation were facts of life for those living in these cramped tenements.

Green's Mill, a red brick tower mill, was built around 1807 on the site of a previous smaller post mill.[10] When the founder of the mill died, his son, renowned mathematician George Green, inherited and operated it until his death in 1841.[11] Near Green's Mill stood the imposing Nottingham Lunatic Asylum, the first County Asylum to open in England, which existed from 1812 to 1902.[12] It was later converted into a boarding school named King Edward's, governed by the infamous head master Alfred Tanner and his wife Mary. Children were killed in industrial accidents at the school.[13] It has since been demolished and is now the location of King Edward Park. At the end of the Nineteenth century, the Third Earl Manvers sold off the remainder of the Pierrepont family land to developers, who subsequently build all of the Victorian housing on the slopes of Sneinton Dale. This housing was of a higher standard than the previous development, and still stands to this day. The population then grew to a peak of 23,093 in 1901,[14] as lace and textile manufacturing expanded along with heavy industry.

Modern period

In the 1930s, Nottingham began to address the problem of overcrowding. Many people in Sneinton at the time were living in the older, cramped, unfit-for-purpose damp Victorian housing.[15] These homes were generally rented, so it was a trivial process use clearance orders to evict tenants. Unfit houses were demolished, and the land redeveloped under the "Carter Gate" redevelopment.[15] Further development was put on hold due to World War II, during which Sneinton was heavily bombed.[15] A map produced by the local Civil Defence Departments showed that many of the industrial units on Meadow Lane received direct hits.[16]

Later in the 1950s came the "Chedworth Estate" redevelopment. A large amount of modern housing was built during this period, as well as five multi-story tower blocks, all of which stand to the present day. Around this time, economic migrants began to settle in Sneinton, drawn by affordable housing near to places of work.

In the 21st century, Sneinton has retained a sense of community, giving it a village-like feel, which has so far resisted gentrification.[17] As of 2014, Sneinton has the 11th lowest crime rate out of the 25 Nottingham districts, beating all other comparable inner city areas (such as St Ann's, the Meadows, and Radford).[18] House prices have risen over the past few decades but housing remains cheaper in Sneinton than in other Nottingham suburbs. This may change when the planned "Eastside" urban renewal projects beside Sneinton are completed.[19]

Regeneration

In the 1930s, the wholesale fruit and vegetable market moved from Slab Square in the city centre to a new location on the edge of Sneinton. This was soon expanded by demolition of decaying dwellings to establish individual brick units arranged in rows for the traders, together with a new market place for stallholders. The area fell into dis-use during the 1980s, and after investment secured from Europe and Nottingham City Council, the area was rejuvenated by conversion of the units into start-up locations for artisan retailers and hospitality. Conversion of the old Brook Street multi-storey telephone exchange into student accommodation brought a greater population with longer trading days,[2][4] and the area gained a nickname of 'Creative Quarter'. Further nearby student accommodation projects are planned.[20]

The old market place was converted into a pedestrian plaza, with the Victoria Baths being extended in 2012 into a larger multi-function leisure facility.[21][22]

Nearby areas under regeneration include Broadmarsh, Hockley and the Lace Market.

Governance

Sneinton was officially incorporated into the borough of Nottingham in 1877. It now lies within the unitary authority of Nottingham, and so is governed by Nottingham City Council. Nottingham has been sending MPs to Westminster since 1295; the constituency was split up in 1885 and Sneinton has been part of Nottingham East ever since. Within the Nottingham East constituency, Sneinton mostly lies within the Dales electoral ward,[23] though the Sneinton Elements estate is included in the St. Anns ward instead.[24]

Geography

Sneinton is the area around Sneinton Dale road, which runs for about two miles east of Nottingham city centre until it turns into Oakdale at a roundabout marking the boundary with the 1930s suburb of Bakersfield to the east. Otherwise the boundaries are blurred - Carlton Road and the A612 Newark road are generally regarded as the northern and southern boundaries of the residential area, but the Dales electoral ward, which includes Sneinton and Bakersfield, extends south of the Newark road down to the river. Thus the ward includes riverside industrial areas, the racecourse, Colwick Woods and Colwick Country Park as they are within the city boundary and Colwick is outside it in Gedling borough. The ward boundary mostly runs south of Carlton Road but some estate agents may describe property north of it around Victoria Park as being in Sneinton rather than the troubled area of St Ann's.[25] The western boundary of the ward comes up from Lady Bay Bridge along the A6011 Meadow Lane which turns into the A612 Manvers Road.

Sneinton sits on soft Bunter sandstone (of the Sherwood Sandstone Group type), overlaid on top of Keuper marls (of the Mercia Mudstone Group).[7][26] Nottinghamshire's sandstone ridges can easily be dug with simple hand tools to create artificial cave dwellings. The general area around what is now Nottingham was once known in the Brythonic language as "Tigguo Cobauc" meaning "The Place of Caves" and was referred to as such by the Bishop of Sherborne Asser in 893 AD in The Life of King Alfred.[27][28] Cave dwellings extended out into Sneinton, wherein they were referred to as the "Hermitage", being as they were occupied by members of a reclusive religious order.[29] When Manvers Road was first constructed, brick buildings were built facing into the sandstone, using the caves as back rooms.[29] In 1829 a rock collapse destroyed these buildings, and in 1897 a railway expansion forced Manvers Road to divert, cutting away much of the rockface, erasing most of Sneinton's remaining caves.[29] What little remains can still be seen along the edge of Sneinton Hermitage.[30]

Demography

In 1801 the population of Sneinton stood at just 558,[31] but by 1851, it had grown to 8,440.[31] The population peaked at 23,093 in 1901.[14]

People from the West Indies, Southern Asia, East Asia, Southeast Asia, The Middle East, Eastern Europe, Southern Europe, Western Europe, Africa, South America and North America are all represented in Sneinton, but the greatest single population comes from Pakistan.[1] As result of this mixed migrant population, the area has a multicultural character, and has a diverse range of restaurants and stores. In 2011, the population stood at 12,689 people, of which 60% was white, 20% Asian, 8% black, 9% mixed, 2% other.[1]

Economy

In the 19th century the local industries were lace and textile manufacturing, like most of Nottingham.[32] In Sneinton, heavier industries were also represented, such as the iron foundry, engineering works, and brickworks, sited at the eastern end of Sneinton Dale.[32] Most of the existing red brick terraced houses were built in the nineteenth century, and many of the factories and warehouses of that era have long since been demolished to make way for additional housing.

Sneinton had a traditional open-air public market situated at the north-western end of Sneinton, where the district meets the city centre. The Market struggled in recent years.[33]

Sneinton Market was substantially altered into a pedestrian plaza for the student quarter.[22] This urban regeneration project has been called "Nottingham Eastside" by developers, and the start date was pushed back numerous times due to a lack of funding during the Great Recession. The Eastside development ties in with Nottingham City Council's ambitions to develop the south eastern part of the city centre into a "Creative Quarter". The area includes the Lace Market, Hockley, Broadmarsh East, the Eastside Island site and BioCity, the project aims at creating growth and jobs. In July 2012, the government contributed £25 million towards a £45 million venture capital fund, mainly targeted at the Creative Quarter.[34]

Sneinton Dale and Sneinton Boulevard, the two main high streets through the village, have weathered the recession. The Sneinton Business Forum represents over 160 local businesses.[35]

Culture

The art gallery Trade is one of a number of projects at One Thoresby St, listed as one of "the world's best secret art galleries" by Alexander Farquharson of Nottingham Contemporary.[36] Sneinton Dale was previously the site of an art deco film house called Dale Cinema, which operated from 1932 to 1957.[37] There are around a dozen public houses in Sneinton, the oldest of which is The Lord Nelson, sited in a 500-year-old building which was originally a coaching inn called The Hornbuckles.[38] The studios of regional radio station Gem 106 are nearby on the City Link.

Festival

Every July, Sneinton holds a festival organised around a different theme. The first festival was held in 1995, and is run by a volunteer group made up of local residents, representatives of local organisations, community groups, schools, church, youth and play groups, artists, musicians, performers and local project workers. Since 2002, the group has been supported and coordinated by the Sneinton Community Project.

The Sneinton Festival has three elements: initial workshops, a week-long festival, and the final carnival. Workshops organised by The Festival Group take place in the run-up to the festival, and bring young people together to be creative around the year's theme, building the artwork, decorations and costumes, as well as holding dance and performance workshops. The Festival Week begins on a Saturday, and involves seven days of arts-based free and open events held in and around Sneinton. Festival Week culminates in a parade held on Carnival Day, on the next Saturday. The Carnival Parade includes floats, fancy dress, costumes, samba bands, jazz bands, youth bands, dancers, and a variety of other event performers. The festival then continues in the Hermitage Square when the parade arrives, and features an afternoon of free and diverse entertainment.

Sites of interest

There are several parks and allotments within Sneinton, such as Belvoir Park and the Dale Allotments, but by far the largest green space is Colwick Woods. Colwick Woods lies to the east of Sneinton, and, at 50 hectares or 123 acres, is almost as large as Sneinton itself. It is a mixture of grassland and ancient woodland, and forms a Local Nature Reserve and a Site of Special Scientific Interest.[39] The ancient woodland is a habitat for indicator species such as dogs mercury and ramsons. The site is rich in mammal species including both species of pipistrelle and noctule bat.[39] Public rights of way are marked out across the site, along with desire paths that run throughout the woods. The woods and meadows, unusually close to a city centre, are very popular with local people for outdoor activities including walking, mountain biking, and other activities.

Steep hills are a characteristic feature of most of the site, and wheelchair access is only from Greenwood Road into the open grassland. Greenwood Dale High School shares a boundary with the reserve and educational events have been held in partnership with the school including photographic scavenger hunts and sapling collection. Open days are held in the summer allowing the public to be actively involved with the reserve. Colwick Woods has an active Friends Group who meet regularly to discuss the condition of the site and carry out wildlife conservation activities in the woods.[39]

Green's Mill is a restored and working 19th century tower windmill, located at the top of Belvoir Hill, overlooking the city of Nottingham. Built in the early 1800s for the milling of wheat into flour, it remained in use until the 1860s. It was renovated in the 1980s and is now part of a science centre, which together have become a local tourist attraction.

The Sneinton Dragon is a large sculpture that stands at the junction of Colwick Loop Road and Sneinton Hermitage. Made from stainless steel, it was created by local craftsman Robert Stubley after residents of Sneinton were asked by the Renewal Trust what they would like to see as a piece of public art to represent their area.[40] It was commissioned by Nottingham City Council and was unveiled on 21 November 2006. The dragon stands 7 feet tall, has a wingspan of 15 feet and took 3 months to finish. During the Christmas period the dragon receives a Santa hat, which often disappears within days. There are also three other sculptures in Sneinton.

Transport

The main High Street through the village is Sneinton Dale. Many of the residential streets in Sneinton are named after battles and generals of the Second Boer War.[41] Sneinton is bounded to the north by the B686 (Carlton Road), and to the west and south by the A612 road (Manvers Street and Colwick Loop Road) which runs from Nottingham to Newark-on-Trent. The railway to Netherfield and Grantham runs through Sneinton but it has not had a station since the Racecourse station shut in 1959. The Nottingham Suburban Railway connected Trent Lane junction in Sneinton with Daybrook, but bomb damage closed the Sneinton end in 1941 and the line ceased operations completely in 1954. Tramlines once ran down Carlton Road.

Buses

- 43: Nottingham - Sneinton Dale - Bakersfield

- 44: Nottingham - Sneinton - Colwick - Netherfield - Gedling

Education

Sneinton has six primary school providers, William Booth Primary School, Edale Rise Primary and Nursery School, Sneinton St Stephen's CofE Primary School, Windmill L.E.A.D. Academy, the Iona School, and The Nottingham Academy (operating from the former Jesse Boot Primary School). Nottingham Academy also runs the only secondary school in the area, on the sites of the former Greenwood Dale and Elliot Durham Schools. Sneinton has a public library, which can be found on Sneinton Dale (at the former Sneinton Police Station site).

Religion

The religious life of Sneinton reflects the diversity of its inhabitants. The main religious denomination has traditionally been the Church of England, which is represented by four churches: St. Christopher's, St. Cyprian's, St. Matthias' and St. Stephen's. St. Stephen's is the parish church at the centre of the parish of "St Stephen with St Matthias".[43] Two former Church of England sites have been taken over by other denominations, namely St Alban's, which is now Catholic, and St. Luke's which is now the Congregation of Yahweh. The former Albion United Reformed Church also lies within Sneinton. St Mary's and St. George's is the local Coptic Christian place of worship, and Bethesda represents the Pentacostal faith. Beyond Christianity, there is also a Hindu Temple & Community Centre on Carlton Road, and the Jamia Masjid Sultania mosque was recently built on Sneinton Dale, giving the Muslim community a place to worship.[44]

Sport

Gyms in the village include the award-winning Victoria Leisure Centre.[45] Carlton Town F.C. is a local football team, that was founded as Sneinton F.C. in 1904.[46] There are two local basketball teams; the men's team is the Beeston Tropics, and the women's is the Nottingham Wildcats.

Notable people

- Sneinton was the birthplace of mathematician George Green (born 1793) who lived in a house beside one of the village windmills, one of which he owned and ran.[47]

- William Booth (born 1829), founder of The Salvation Army, was born in the house which is now The William Booth Birthplace Museum, located on Notintone Place.[48]

- Another famous son of Sneinton was bare knuckle boxing champion, William Thompson, better known as Bendigo. A former pub in the area still bears a statue of the figure above its door.[49] It was later renamed as The Hermitage, then it closed.[50][51]

- Lydia Beardsall, mother of D.H. Lawrence, came from Sneinton and married Arthur Lawrence in St Stephen's on 27 December 1875.[52]

- A more recent Sneinton celebrity is the film director Shane Meadows who lived in Sneinton and filmed some of his early works partly in Sneinton, including Small Time in 1996.

Statue of William Booth, on Notintone Place

Statue of William Booth, on Notintone Place Statue of Bendigo on the former Hermitage pub

Statue of Bendigo on the former Hermitage pub

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Census 2011: Key and Quick Statistics (Census Communities - Nottingham City)". Nottingham City Council. 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- 1 2 Controversial student accommodation extension approved, despite multiple objectionsNottinghamshire Live, 24 September 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2022

- ↑ Sneinton businesses face worry over plans to demolish buildings for student flats Nottinghamshire Live, 22 April 2022. Retrieved 10 November 2022

- 1 2 Our history Sneinton Market Avenues. Retrieved 10 November 2022

- ↑ David Mills (20 October 2011). A Dictionary of British Place-Names. Oxford University Press. p. 350. ISBN 978-0-19-960908-6.

- 1 2 Percy Whatnall (1928). "Ancient woodwork in Sneinton parish church". Nottinghamshire History. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 Robert Mellors (1914). "Sneinton then and now: Name". Nottinghamshire History. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ↑ "Population statistics Sneinton Ch/CP through time". A Vision of Britain through Time. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ↑ "Relationships and changes Sneinton Ch/CP through time". A Vision of Britain through Time. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ↑ Denny Plowman (December 1993). Green's Mill, Its History and Working. Department of Leisure and Community Services, City of Nottingham. ISBN 978-0-905634-31-9.

- ↑ Susan Friedlander; Powell, Anton (Fall 1989). "The mathematical Miller of Nottingham". The Mathematical Intelligencer. 11 (4): 38–40. doi:10.1007/bf03025884.

- ↑ Terry Fry (20 July 2008). "The General Lunatic Asylum, Nottingham, 1812–1902 (also known as Sneinton Asylum)". Thoroton Society. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ↑ "St Ann's and Sneinton Area Home Page". Notts Watch. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- 1 2 Barry Bruff (1990). The Village atlas: the growth of Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire, 1834–1904. Alderman. ISBN 978-1-85540-026-9.

- 1 2 3 "How the past 300 years have brought many changes to the small village near brickworks". Nottingham Post. 17 April 2013. Archived from the original on 10 March 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ↑ Giga Nottstalgian (28 April 2009). "I found the map showing all the bombs dropped on Nottingham during WW2, it's quite interesting, but tragic when you study it". nottstalgia.com. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ↑ "Neighbourhood Design Vision: Sneinton" (PDF). Sneinton Alchemy and OPUN. 23 April 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ↑ "Neighbourhood crime league table". UKCrimeStats.com. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ↑ Tom Hughes (14 March 2013). "Gentrification- not our problem?". Sneinton Alchemy. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ↑ Bendigo Building, 1 Brook Street Nottingham City. Retrieved 11 November 2022

- ↑ The dark past of the Nottingham leisure centre once used as a morgue during 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic Nottinghamshire Live, 21 November 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2022

- 1 2 10 Years of Skateboarding at Sneinton Market creativequarter.com, 20 April 2022. Retrieved 10 November 2022

- ↑ "Nottingham City Council: Dales Ward" (PDF). Nottingham Insight. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ "Nottingham City Council: St Anns Ward" (PDF). Nottingham Insight. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ "1 bedroom apartment for sale in Bath Street, Sneinton, Nottingham NG1". Rightmove. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- ↑ F.G. Bell and M.G. Culshaw (February 1998). "Petrographic and engineering properties of sandstones from the Sneinton Formation, Nottinghamshire, England". Quarterly Journal of Engineering Geology and Hydrogeology. 31: 5–19. doi:10.1144/GSL.QJEG.1998.031.P1.02. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ↑ "A tour of the caves underneath the city of Nottingham". Demotix. Archived from the original on 6 May 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ↑ H H Swinnerton (1910). "Meaning and Origin of the Words. Shire and County". Nottinghamshire History. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 Robert Mellors (1914). "Sneinton then and now: The Hermitage". Nottinghamshire History. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ↑ "Nottingham Miscellany: Sneinton Hermitage". Nottingham 21. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- 1 2 Roy A. Church (5 November 2013). Economic and Social Change in a Midland Town: Victorian Nottingham 1815–1900. Routledge. p. 166. ISBN 978-1-136-61695-2. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- 1 2 Robert Mellors (1914). "Old Nottingham suburbs: then and now: Manufactures". Nottinghamshire History. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ↑ Peter Blackburn (31 July 2013). "Dead rats, burglars and rubbish: why is Sneinton Market in freefall?". Nottingham Post. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ↑ "Nottingham plans creative hub with 'City Deal' cash". BBC. 5 July 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ↑ "About Sneinton Business Forum". Archived from the original on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ↑ "The world's best secret art galleries". The Independent. 8 October 2011.

- ↑ "Film lovers in Nottingham had choice of 50 cinemas during screen industry heyday". Nottingham Post. 26 June 2014. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ↑ Aaron Bulley (12 July 2013). "A Survey of Sneinton". Trails of Ales & Tales. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Friends of Colwick Woods: About". Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ↑ Alan Lodge (28 November 2006). "Dragon discovered in Sneinton". UK Indymedia. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ↑ Amos, Denise. "The Boer War". Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ↑ "Dales Nottingham 2011 Census Data". Nottingham City Council. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ↑ "Sneinton: St Stephen". Southwell & Nottingham Church History Project. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ↑ Ben Ireland (25 February 2014). "Joy as Notts' first minaret installed at Sneinton mosque". Nottingham Post. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ↑ "Victoria Leisure Centre wins architecture award". BBC News. 22 June 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ↑ "Carlton Town History". Pitchero football network. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ↑ "George Green". School of Mathematics and Statistics: University of St Andrews. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ↑ Roy Hattersley (1999). Blood and Fire: William and Catherine Booth and the Salvation Army. Little Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-85161-9.

- ↑ Old 'eyesore' pub with Bendigo statue could be turned into flats Nottinghamshire Live, 8 September 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2022

- ↑ Richard Studeny. "Nottinghamshire legends: Bendigo". BBC. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ↑ Time called on plans to turn former pub into flats thebusinessdesk.com, % November, 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2022

- ↑ Worthen, John (1991). D. H. Lawrence: The Early Years 1885-1912: The Cambridge Biography of D. H. Lawrence. Cambridge University Press. p. 16. ISBN 9780521254199.