Commodore Nut | |

|---|---|

Commodore Nutt in uniform, c. 1865 | |

| Born | George Washington Morrison Nutt April 1, 1848 |

| Died | May 25, 1881 (aged 33) New York City, U.S. |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Entertainer |

| Employer | P. T. Barnum |

| Known for | Rivaling General Tom Thumb for the hand of Lavinia Warren |

| Height | 29–30 in (74–76 cm) (at his 1862 debut) 42 in (110 cm) (at his death) |

| Spouse | Lilian Elston of Redwood City, California |

George Washington Morrison Nutt (April 1, 1848 – May 25, 1881), better known by his stage name Commodore Nutt, was an American dwarf and an entertainer associated with P. T. Barnum. In 1861, Nutt was touring New England with a circus when Barnum hired him to appear at the American Museum in New York City. Barnum gave Nutt the stage name Commodore Nutt, a wardrobe that included naval uniforms, and a miniature carriage in the shape of an English walnut. Nutt became one of the Museum's major attractions.

Nutt was in love with Lavinia Warren, another dwarf at the American Museum. Lavinia was several years older than Nutt. She thought of him only as a "nice little boy". She married General Tom Thumb in a spectacular wedding masterminded by Barnum in 1863. Nutt went to the wedding as Thumb's best man, but resented his place in the show. He stayed away from women for a long time after the wedding. In 1879, he married Lilian Elston of Redwood City, California.

Nutt toured the world between 1869 and 1872 with the Thumbs and Minnie Warren, Lavinia's sister. They returned to America rich beyond their dreams after appearing before royalty around the world. Nutt left Barnum's employ after a disagreement with the showman. He toured with a comic opera company, put together a variety show on the United States West Coast, and operated western saloons in Oregon and California. He returned to New York City, and died there of Bright's disease in May 1881.

Birth and family

George Washington Morrison Nutt was born in Manchester, New Hampshire, to Major Rodnia Nutt (1810–1875), and his wife Maria (Dodge) Nutt (1807–1859) of Goffstown, New Hampshire.[1] Rodnia was a rich farmer,[2] a Manchester city marshal, and a Manchester city councilman.[3][4]

The Nutts had five children. The first, whose name and sex are not known, was born on 8 December 1837. James Dodge was born on 28 January 1838, and Rodnia Jr. on 11 October 1840. A daughter, Mary Ann, was born on 22 September 1844. According to Nutt family records, George Washington Morrison was born on 1 April 1848.[1][5]

Nutt and his wife were "large, hearty folk".[4] Mr. Nutt weighed over 250 pounds (110 kg).[4] Their sons Rodnia Jr. and George Washington Morrison were dwarfs. In 1861, Rodnia Jr. was about 49 inches (120 cm) tall, and George was about 29 inches (74 cm). George weighed about 25 pounds (11 kg).[6]

Ancestry

George's ancestors include William Nutt (1698–1751), a weaver of English ancestry. William left Derry, Ireland, for North America in the early 18th century. He started a family in colonial New England. A part of Manchester was called Nutfield in the early days of colonization. A pond and a road near the pond were named for early Nutt colonists.[1]

P. T. Barnum and the American Museum

Nutt's career as an entertainer may have started in 1854. He may have been a performer with a small circus in Manchester. The circus manager, William C. Walker, once wrote that he discovered Nutt. He also wrote that he was the first to show him.[7]

Nutt was being exhibited and touring the New England countryside with a manager named Lillie when P. T. Barnum learned of him. Lillie was charging as little as a nickel to see the boy whose education had been neglected. Barnum was disgusted. Lillie knew nothing about exhibiting the boy "in the proper style", as Barnum put it.[2][8]

Barnum met Nutt in 1861 when the boy went to the American Museum in New York City. In his autobiography, Barnum wrote that Nutt was "a most remarkable dwarf, who was a sharp, intelligent little fellow, with a deal of drollery and wit. He had a splendid head, was perfectly formed, and was very attractive, and, in short, for a 'showman' was a perfect treasure."[9]

Barnum knew Nutt could be a major museum attraction. He hired a lawyer to lure Nutt away from his manager. Following Barnum's orders, the lawyer offered Nutt's parents a large sum of money to sign their son to a five-year contract. He promised them that the boy would be taught to be "a genteel, accomplished attractive little man".[10]

A contract was signed on 12 December 1861. Barnum hired the 13-year-old, 29-inch (74 cm) George and his 21-year-old, 49-inch (120 cm) brother, Rodnia Jr. The contract required Barnum to give both young men food, clothing, a place to live, and the costs of travel and medical care. Barnum promised to take care of the moral and academic education of the brothers.[11]

Salaries would start at US$12 per week with increases every year. The two brothers would each get $30 per week in the fifth and last year of their contract. They would also get 10% from the sales of their souvenir books and photographs, with at least $240 the first year and $440 the last year. At the end of the fifth year, they would receive a carriage and a pair of ponies from Barnum.[11]

Publicity campaign

Once the contract was signed, Barnum started a publicity campaign to prepare the public for Nutt's debut. He let reporters think he was trying to hire the dwarf. When other showmen heard this rumor, they rushed in to offer Nutt's parents huge sums of money to be the first to sign their son.[12]

Barnum was pleased. The publicity created much excitement. In a letter he leaked to reporters, he wrote that he was forced to outbid the competition. The showman claimed to have paid $30,000 to hire the dwarf. The boy then became known as "The $30,000 Nutt".[12]

Barnum gave the dwarf the stage name Commodore Nutt. In addition, he provided Nutt with a wardrobe that included miniature naval uniforms.[13] For the Commodore's jaunts about town, the showman had a little carriage built for him. This carriage looked like an English walnut. The top of the vehicle was hinged. When the top was lifted, the little Commodore could be seen sitting inside.[12]

Nutt's carriage was pulled by Shetland ponies. It was driven around New York by Rodnia Jr. dressed in the uniform of a coachman.[14] Barnum thought these little trips about town the best form of advertisement.[15] Nutt's carriage is now in the Barnum Museum in Bridgeport, Connecticut.[12][16]

Debut

Commodore Nutt made his debut at Barnum's American Museum in February 1862. He was a great success.[12] Some museum-goers believed they were being "humbugged" by Barnum though. They thought that Nutt was really General Tom Thumb in disguise.[14]

Nutt did look like the Tom Thumb of the past, but Thumb had aged and put on weight over the years—a fact museum-goers either forgot or ignored.[17] Nutt was a scamp; he took pleasure in the public's confusion, and encouraged the error.[14]

When Nutt debuted, Thumb was touring the American South and West. Barnum wanted to silence those with doubts at the Museum. He asked Thumb to cut his tour short, return to New York, and perform on the same stage with Nutt. Thumb returned to New York.[14]

The little men were billed as "The Two Dromios"[18] and "The Two Smallest Men, and Greatest Curiosities Living." The exhibit opened on 11 August 1862.[17] Despite what their eyes witnessed, some museum-goers still said that Nutt was Tom Thumb in disguise. Barnum wrote, "It is very amusing to see how people will sometimes deceive themselves by being too incredulous."[14][19]

About two months after his debut, Nutt met with New York City Police Department officers. He applied for and was given a policeman's job. He ordered a uniform. Then he sent a telegram to the officers of the Ninth Precinct telling them that he had just gotten a job on the Broadway Squad—with "extraordinary powers to arrest" people outside the Museum and to "take [them] upstairs".[20]

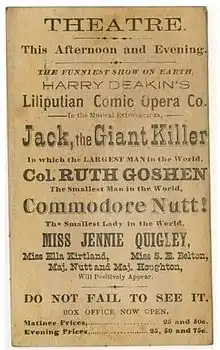

A playbill for Jack the Giant Killer

A playbill for Jack the Giant Killer Commodore Nutt as Ajax defying the thunder, 1864

Commodore Nutt as Ajax defying the thunder, 1864

President Lincoln

President Abraham Lincoln asked Barnum and Nutt to come to the White House in November 1862. When the two arrived, Lincoln left a cabinet meeting to welcome them. Nutt asked Salmon P. Chase, the Secretary of the Treasury, if he was the man who was spending so much of Uncle Sam's money. Edwin M. Stanton, Secretary of War, interrupted to say that he was the man. "Well," said Nutt, "It is in a good cause, anyhow, and I guess it will come out all right."[9][12]

As Barnum and Nutt were on their way out, President Lincoln shook Nutt's hand. He told the Commodore that he should "wade ashore" if his "fleet" was ever in danger. Nutt looked up and down Lincoln's long legs. "I guess, Mr. President", he said, "You could do that better than I could."[9][12]

Personal life

Lavinia Warren

Mercy Lavinia Warren Bump was a dwarf who taught school in her hometown of Middleborough, Massachusetts. She was traveling on a showboat-museum in the Midwest however when Barnum learned of her. He hired her in 1862. Her name was shortened to Lavinia Warren. She first appeared at the Museum in 1863. Warren was 21 years old, 32 inches (81 cm) tall, and weighed 29 pounds (13 kg). Barnum billed her as "The Queen of Beauty". Nutt developed an "adolescent crush" on her, but would be disappointed.[21]

Barnum gave Lavinia a diamond and emerald ring. It did not fit her finger properly, so he told her to give the ring to Nutt as a token of her friendship. Nutt regarded the ring as a token of her love instead. He fell more in love with her than ever. Lavinia was uncomfortable with his attentions. She thought of herself as "quite a woman", but regarded Nutt as just a "nice little boy".[22]

Thumb was not appearing in New York City when Lavinia was hired, but he met her when he visited the Museum in the autumn of 1862. He told Barnum the same day that he had fallen in love with her.[17] Thumb wanted Barnum on his side in this love affair (rather than on Nutt's side), so he quietly promised Barnum he would marry Lavinia in a public ceremony.[15] Barnum knew at once that such a spectacle would make him a fortune. He told Lavinia to take Thumb's romantic interest seriously. He reminded her that the little man was rich.[23]

Thumb's rival

Nutt knew that Thumb was in love with Lavinia. He was jealous. He had a fight with Thumb in a dressing room at the Museum. He threw him on the floor and beat him up. Nutt invited himself along when Lavinia was asked to Barnum's home for a weekend visit. Little did he know that Thumb and his mother would be there, too.[17]

Nutt left New York City on a train late Saturday night. He got to Barnum's house about 11 pm. He found Thumb and Lavinia alone in the downstairs parlor. Thumb had proposed, and Lavinia had accepted. Nutt only learned of their engagement a week later when Lavinia and Barnum told him.[17] Nutt had a hard time forgiving both Thumb and Barnum for (as he termed it) this "dastardly" offense.[15]

Preparations

Lavinia's younger sister Minnie was much smaller than she was. Barnum thought she would make a good match for Nutt. He asked Nutt to think about marrying Minnie. Nutt told Barnum he had little faith in women. He said that he would not marry "the best woman living".[17]

Barnum wanted Minnie and Nutt to go to the wedding as Lavinia and Thumb's bridesmaid and best man. Nutt refused. Later, Thumb himself asked Nutt to be his best man. Nutt accepted. He told Barnum, "It was not your business to ask me. When the proper person invited me, I consented."[17]

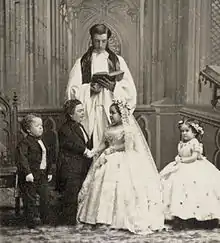

Barnum's "Fairy Wedding"

Thumb and Lavinia were married at Grace Episcopal Church, New York City, on Tuesday 10 February 1863. Nutt and Minnie were best man and bridesmaid at the "Fairy Wedding". Police stopped traffic as people gathered in the streets to see the arrival of the wedding party. The wedding was scheduled to start at noon, but the bride did not arrive until 12:30 pm.[24] Barnum led the wedding party down the center aisle.[25]

Two thousand people were invited to the wedding. Mrs. John Jacob Astor, Mrs. William H. Vanderbilt, Mrs. Horace Greeley, and General Ambrose Burnside were there.[17][26][27] Members of the church complained about the "marriage of mountebanks". They became irate when they were told they could not sit in their own pews. Much of the public curiosity about the marriage was based on an interest in the sexual mechanics of Thumb and Lavinia. Barnum did not encourage or discourage this interest.[26]

The wedding reception was held in the Metropolitan Hotel on Broadway at 3 pm.[24][25] The four little members of the wedding party stood on top of a grand piano so they could be seen by everyone.[25] Nutt gave Lavinia a diamond ring as a wedding present.[24] Americans loved the wedding. It was welcome relief from the horrors and sorrows of the war.[28]

World tour and aftermath

People around the world took great interest in the wedding. Barnum thought this was a chance to make a lot of money. He sent the members of the wedding party on long, successful tours of America and Europe. The four dwarfs were sent off again—this time on a grand tour of the world as The Tom Thumb Company.[6]

The four little people left the United States on 21 June 1869.[29] They travelled 60,000 miles (97,000 km) around the world, visited 587 cities and towns, and gave 1,471 performances of songs, speeches, and military drills. They returned to America in 1872. Nutt and Barnum argued after the tour. Nutt quit. He joined Harry Deakin's Lilliputian Comic Opera Company. This company toured America in an operetta called Jack, the Giant Killer.[30][31]

Nutt and his brother Rodnia put together a variety show. It played in Portland, Oregon. It was not a success. Nutt went to San Francisco, California, and put together another show. He tired of the life within a year and quit. Another show he put together about this time was not successful either.[31] Nutt ran a couple of saloons in Oregon and San Francisco, but these were not successes.[23]

Last years

Newspapers reported at least four times that Nutt and Minnie were married. They were close friends, but never husband and wife. Minnie married a song and dance man who performed on roller skates named Edmund Newell.[17] She died while having their baby in 1878.[32]

One day long after the wedding of the Thumbs, Barnum asked Nutt why he had not married. "Sir, my fruit is plucked", he said, "I have concluded not to marry until I'm thirty." His bride's height was of no concern, he said, but he did "prefer marrying a good, green country girl to anyone else."[17]

In 1879, Nutt married Miss Lilian Elston of Redwood City, California. He had met her while he was touring the American West. She was a bit shorter than most women, but not a dwarf.[15]

After his failures on the West Coast, Nutt went back to New York City. He bought a saloon. One day, he was caught selling liquor without a license. The New York City courts closed his saloon.[23] Nutt was in charge of an amusement area called Rockaway Pier for a time. He returned to performing with an act called "Tally-Ho".[31]

Death

Early in 1881, Nutt had an attack of Bright's disease (nephritis). He was sick for more than two months. He died on 25 May 1881 at the Anthony House in New York City. Nutt's wife cried over his coffin at the funeral. She called him her "dear little boy", and said that he was "so good".[15] Nutt was buried in Merrill Cemetery at Manchester, New Hampshire.[33]

His grave is unmarked. It is thought that he was buried in a spot either next to or possibly between his parents, or between the siblings that were also interred in the family plot.

Nutt had grown from his original 29 inches (74 cm) to 43 inches (110 cm), and weighed a little less than 70 pounds (32 kg) at his death.[15] In 1891, the editors of Appleton's Cyclopedia wrote, "Commodore Nutt was distinguished for large-hearted virtues that are often lacking in bigger men; his genial temper was allied to constancy and generosity that entitle his memory to the highest respect." The editors noted that Nutt was "for many years faithful to an early love."[34]

Notes

- 1 2 3 "The Nutt Family of Derryfield, New Hampshire, Family Tree (Genealogy)". History and Genealogy of Manchester, Hew Hampshire. Searchroots. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- 1 2 Ogden 1993, p. 259.

- ↑ Eastman 1897, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 Appleton's 1891, p. 686.

- ↑ Saxon 1989, p. 383.

- 1 2 Saxon 1989, p. 209.

- ↑ Saxon 1989, p. 382.

- ↑ Saxon 1989, p. 206.

- 1 2 3 Barnum 1888, p. 283.

- ↑ Saxon 1989, pp. 206–207.

- 1 2 Saxon 1989, p. 207.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Saxon 1989, p. 208.

- ↑ Ogden 1993, p. 360.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Barnum 1888, p. 280.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Commodore Nutt Dead: The History of the Well-Known Dwarf". The New York Times. May 26, 1881.

- ↑ "Barnum's New Lilliputian". The New York Times. January 16, 1862.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Ogden 1993, p. 261.

- ↑ A reference to characters in Shakespeare's The Comedy of Errors who are twins.

- ↑ Harris 1981, p. 162.

- ↑ "A Distinguished Visitor to Police Headquarters". New York Daily Tribune. April 18, 1862.

- ↑ Saxon 1989, pp. 208–209.

- ↑ Barnum 1888, p. 288.

- 1 2 3 Hartzman 2006.

- 1 2 3 Hornberger 2005, p. 24.

- 1 2 3 Wilson 2013, p. 152.

- 1 2 Harris 1981, p. 163.

- ↑ Wilson 2013, p. 151.

- ↑ Streissguth 2009, p. 84.

- ↑ Roberts 1899, p. 71.

- ↑ Western 1881, p. 609.

- 1 2 3 Appleton's 1891, p. 687.

- ↑ Blom 1983, p. 388.

- ↑ "Cemeteries". City of Manchester, New Hampshire. September 22, 2011. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ↑ Appleton's 1891, pp. 686–687.

References

- Appleton's Annual Cyclopædia and Register of Important Events of the Year 1881, vol. 6, D. Appleton and Company, 1891

- Barnum, Phineas Taylor (1888), How I Made Millions: the life of P. T. Barnum, New York: G. W. Dillingham

- Blom, Thomas E., ed. (1983), Canada Home: Juliana Horatia Ewing's Fredericton letters, 1867–1869, UBC Press, ISBN 978-077-485-768-0

- Roberts, Mary Shears (1899). Dodge, Mary Mapes (ed.). "General Tom Thumb". St. Nicholas. New York: Scribner & Co. 27 (1): 70–77.

- Eastman, Herbert W., ed. (1897), Semi-centennial of the City of Manchester, New Hampshire, John B. Clarke Company

- Harris, Neil (1981), Humbug: the art of P. T. Barnum, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-022-631-752-6

- Hartzman, Marc (2006), American Sideshow : an encyclopedia of history's most wondrous and curiously strange performers, Penguin, ISBN 978-1-440-64991-2

- Hornberger, Francine (2005), Carny Folk: The World's Weirdest Sideshow Acts, Citadel Press/Kensington Publishing Corporation, ISBN 978-080-652-661-4

- Ogden, Tom (1993), Two Hundred Years of the American Circus: from Aba-Daba to the Zoppe-Zavatta Troupe, Facts On File, Inc., ISBN 978-081-602-611-1

- Saxon, A. H. (1989), P. T. Barnum : the legend and the man, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-023-105-687-8

- Streissguth, Tom (2009), P. T. Barnum: Every Crowd Has a Silver Lining, Enslow Publishers, Inc., ISBN 978-076-603-022-0

- History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, The Western Historical Company, 1881

- Wilson, Robert (2013), Mathew Brady: portraits of a nation, Bloomsbury Publishing USA, ISBN 978-162-040-204-7