Hijab in Iran, the traditional head covering worn by Muslim women for modesty for centuries, have been practiced as a compulsion supported by law in Iran after the 1979 revolution.[2] In the 1920s, a few women started to appear unveiled. Under Reza Shah, it was discouraged and then banned in 1936 for five years. Under Reza Shah's successor, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, hijab was considered "backward" and rarely worn by upper and middle-class people. Consequently, it became a symbol of opposition to the shah in 1970s, and was worn by women (educated, middle and upper class) who previously would have been unveiled.

After the 1979 Iranian Revolution and overthrow of the Pahlavi dynasty, veiling again was encouraged, and in 1981 the covering of hair and wearing of loose-fitting clothing covering all but hands and face was made legally mandatory for women.[3][4] Since the death of Mahsa Amini in 2022, hijab has again become a political symbol, this time of opposition to the Islamic Republic, and defiance of the law by younger women has been observed "in towns and cities" and been called "too widespread to contain and too pervasive to reverse".[5] As of April 2023, however, the Islamic Republic has vowed to enforce the "divine decree" of the hijab.[6]

Through the order of minister of industry, mining and commerce Hijab was made tax exempt in 2023, and IRGC Basij began permanent exhibition called "Hijab city" in Tehran and Isfahan cities.[7] In August 2023, Etemad reported veil Chador could have possibly become mandatory for women in the universities.[8][9]

The UN has called the Iranian government gender apartheid.[10] In September 2023, the Iranian government opened a public mobile app website for Monitors (ordinary people and/or its informant agents) to report women that don't wear full hijab.[11]

For university students, talking with the opposite sex was criminalized, as was wearing perfume.[12]

Subway trains were sex segregated in September 2023.[13]

Waves of Iranian women removing their Hijab has been likened to the fall of the Berlin wall.[14]

Wearing clothes that don't cover the neck or thigh or showing one's ankles or forearm is considered illegal.[15]

History

Leading up to the Islamic Revolution of 1979, the wearing of hijab by educated middle-class women began to become a political symbol—an indication of opposition to the Pahlavi modernization policy and thus of Pahlavi rule.[16] Many middle-class working women starting to use it as such.[16]

Not only simple hijab but the traditional Shi'i chador became popular among the middle class opposition, as a symbol of revolutionary advocacy for the poor, as protest of the treatment of women as sex objects, to show solidarity with the conservative women who always wore them, and as a nationalist rejection of foreign influence.

Hijab was considered by conservative traditionalists as a sign of virtue, and thus unveiled women as the opposite. Rather than a sign of backwardness, unveiled women came to be seen as a symbol of Western cultural colonialism; Westoxication" (Gharbzadegi) or infatuation with western culture, education, art, consumer products etc., "a super-consumer" of products of Imperialism, a propagator of "corrupt Western culture", undermining the traditionalist conception of "morals of society", and as overly dressed up "bourgeois dolls", who had lost their honor.[17]: 144

Feminist hijab advocates pointed out that traditionally women not only wore hijab but did not mix with men, but in the anti-shah demonstrations thousands of veiled women participated in religious processions alongside men, which showed hijab empowered women protecting women from sexual harassment (because conservative men regarded them as more respectable) and enabling access to public spheres.[18]

Islamic Republic

.jpg.webp)

After the Islamic Revolution and founding of the Islamic Republic, the Kashf-e hijab was reversed. Instead of prohibiting veils, the law now required them,[17] a process that worked in stages.[4] In spring of 1979 (shortly after the overthrow), leader of the revolution Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini announced that women should observe Islamic dress code.[19] He was supported in his by the conservative/traditionalists fraction of the revolutionaries who were hostile to unveiled women, as expressed in two slogans used during this time: "Wear a veil, or we will punch your head" and "Death to the unveiled".[19]

Non-conservative/traditionalist women, who had worn the veil as a symbol of opposition during the revolution, had not expected veiling to become mandatory. Almost immediately after, starting from 8 March 1979 (International Women's Day), thousands of liberal and leftist women began protesting against mandatory Hijab.[17][20] The protests lasted six days, until 14 March. The protests resulted in the (temporary) retraction of mandatory veiling,[17] and government assurances that Khomeini's statement was only a recommendation.[4][21]

Khomeini, denied that any non-hijab wearing women were part of the revolution, telling Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci in February 1979:

"the women who contributed to the revolution were and are women who wear modest clothes. ... these coquettish women, who wear makeup and put their necks, hair and bodies on display in the streets, did not fight the Shah. They have done nothing righteous. They do not know how to be useful, neither to society, nor politically or vocationally. And the reason is because they distract and anger people by exposing themselves."[19]

As the consolidation of power by Khomeini and his core supporters continued, left and liberal organizations, parties, figures, were suppressed and eliminated, and mandatory veiling for all women returned.[17] This began with the 'Islamification of offices' in July 1980, when unveiled women were refused entry to government offices and public buildings, and banned from appearing unveiled at their work places under the risk of being fired.[22] On the streets, unveiled women were attacked by revolutionaries.[19]

In July 1981 an edict of mandatory veiling in public was introduced (including for non-Muslims and non-citizens), women and girls over 9 must cover their hair, and hide the shape of their bodies under long, loose robes;[5] this was followed in 1983 by an Islamic Punishment Law, introducing a punishment of 74 lashes on women who failed to cover their hair in public.[20]: 67 [4]

Since 1995, unveiled women can also be imprisoned for up to 60 days.[19] Under Book 5, article 638 of the Islamic Penal Code, women in Iran who do not wear a hijab may be imprisoned from 10 days to two months, and/or required to pay fines from 50,000 up to 500,000 rials adjusted for inflation.[23][24] The law was enforced by members of the Morality Police who patrolled the streets—first the Islamic Revolution Committees, later by Guidance Patrols.

More than one source has emphasized the importance to the Islamic Republic of enforcing hijab in Iran, calling it "tantamount" to the Islamic Republic's "raison d'etat", a core pillar of Iranian state ideology,[19] Since the 1979 Islamic revolution, after all, the role of women in society constitutes "a core pillar" of "state ideology".[19] "a symbol" of the "success" of the Islamic Republic.[5] However, how diligently the law is enforced has varied over the years, "depending on which political faction" holds power.[5]

Enforcing the compulsion

There are several parts of the government that have the responsibility and eligibility to make laws and enforce them to people regarding the matter of compulsory hijab. First of all, the morality police or Gasht-e Ershad, which are units of the Iranian security forces that patrol the streets and public places to monitor the compliance of women with the hijab law.[25][26][27] Also, the Headquarters for Enjoining the Good and Forbidding the Evil, which is a state institution that oversees the implementation of the hijab law and coordinates with other agencies to control mal-veiling.[28] The judiciary, which is the branch of the government that prosecutes and punishes women who violate the hijab law, with penalties ranging from fines and lashes to imprisonment and Flagellation.[29][30][31] The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which is a paramilitary force that cooperates with the judiciary and the morality police to suppress women who protest against the hijab law.[32][33] The parliament, which is the legislative body that drafts and approves laws and regulations related to the hijab law and sets the criteria and indicators for proper veiling.[34][35]

In 2023, the Minister of Islamic Culture and Guidance announced they have a new The Bureau of Chastity Living, it is to parallel work to country's public culture council.[36][37]

Law enforcement command

Facial recognition cameras, a product of Bosch, were deployed for use.[38][39] In the 2023 law business places that are reported to not force women hijab receive fine up to %10 percent annual gross profit.[40] A uniform was issued for waitresses in entire city of Mashhad.[41]

The fines are withdrawn from the person's bank account by the government.[42]

In a move interpreted as a declaration of war against the people the government made it so doctors can't visit unveiled females.[43]

Municipality in Tehran city in August 2023 hired 400 hijab guards (hijabban) they report and then make arrest.[44] In August 2023, law minor girls who don't wear hijab can't go to school, aren't allowed to be hired in the future, can't get a passport, can't have a mobile phone, can't have a bank account, or internet access.[45]

In August 2023, Iranian MPs have voted to review a controversial hijab law behind closed doors, potentially avoiding public debate. The proposed "Hijab and Chastity Bill" would impose stricter penalties on women not wearing headscarves, prompted by protests over the death of a woman in custody. The decision to use Article 85 of Iran's constitution allows for a three to five-year trial period, pending approval from the powerful Council of Guardians.[46]

Penalties

| Crime | Highest Charge/Punishment | Fine |

|---|---|---|

| Foreigner without hijab |

|

Article 23 Islamic criminal code[48] |

| Not wearing hijab out on the street / Removing own hijab in public (kashf hijab) | 1st time 6th degree maximum punishment, second time fifth degree misdemeanor |

|

| public nudity (not wearing full hijab) or semi nude (improper clothes) |

|

|

| Not wearing hijab in car and on motor bike | 500 thousand toman traffic fine, 3 to 6 month car confiscation after second notice |

|

| Collaborating with enemy countries, media, foreign groups against hijab |

|

|

| Insulting hijab online or in real life and or advertising not wearing hijab |

|

|

| Working advertisings without/or against hijab wearing |

|

|

| Anti hijab wearing advertising action by businesses, workplaces and or employee |

|

|

| Celebrities without/ not wearing hijab |

|

|

| Selling / imported forbidden dresses and clothes |

|

|

| Production / distribution of banned dresses / clothes |

|

|

| Designing of banned dresses / clothes |

|

|

| Deleting/ hiding CCTV footage tape from FARAJA |

|

|

| Government worker/employees not wearing properly hijab | Fired and barred for up to 6 month- 2 years from government services | |

| Insulting / abusing hijabi wearing women |

|

|

| Insulting Muslims who attempted guide person to hijab | Sixth degree | 6-24 million toman |

| Extra insulting Muslims who attempted to guide person to hijab | Fifth degree | 24-50 million toman |

Types

_comprando_en_el_bazar.jpg.webp)

"Hijab" can mean Islamic modest dress in general. It can also mean covering of the head. Common styles for women in Iran that follow the law covering the head, the hair, arms, legs and ankles and hide the body shapes are:[49]

- chador—this is a traditionally black covering, a long piece of black cloth covering their whole body from head to ankles and "is generally used by the most religious women especially in rural areas or in the most devout cities";[49]

- Other hijab are:[49]

- shawl,

- foulard,

- pashmina,

- scarf,

- covering body shape,[49]

- manteau (a long coat),

- cardigan,

- long shirt.

Movements

Protest, White Wednesday

In May 2017, My Stealthy Freedom, an Iranian online movement advocating for women's freedom of choice, created the White Wednesday movement, a campaign that invites men and women to wear white veils, scarves, or bracelets to show their opposition to the mandatory forced veiling code.[50] The campaign resulted in Iranian women posting pictures and videos of themselves wearing pieces of white clothing to social media.[50] Masih Alinejad, the Iranian-born journalist and activist based in the UK and the US, who started the protest in 2017,[51] described it in Facebook, "This campaign is addressed to women who willingly wear the veil, but who remain opposed to the idea of imposing it on others. Many veiled women in Iran also find the compulsory imposition of the veil to be an insult. By taking videos of themselves wearing white, these women can also show their disagreement with compulsion."[51][52]

Protest, Vida Movahed

On 27 December 2017, a White Wednesday protester, 31-year-old Vida Movahed, also known as "The Girl of Enghelab Street" was arrested. A video of her silently waving her white hijab headscarf on a stick while unveiled for one hour on Enqelab Street in Tehran[53][54] went viral on social media.[54][55][56] On social media, footage of her protest was shared along with the hashtag "#Where_Is_She?" On 28 January 2018, human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh announced Movahed had been released,[57][58] In the following weeks, multiple people re-enacted Movahed's public display of removing their hijabs and waving them in the air.[54]

On 1 February 2018, the Iranian police released a statement saying that they had arrested 29 people, mostly women, for removing their headscarves.[54][59] One woman, Shima Babaei, was arrested after removing her headdress in front of a court.

On 23 February 2018, Iranian Police released an official statement saying that any women found protesting Iran's compulsory veiling code would be charged with "inciting corruption and prostitution," which carries a maximum sentence of 10 years in prison.[60] considerably harsher than regular sentences of two months imprisonment or up to 74 lashes; or a fine of five hundred to fifty thousand rials for being without hijab.[61]

Following the announcement, multiple women reported being physically abused by police following their arrests,[60] some sentenced to multiple years in prison.[62] In one video, an unveiled woman is tackled by a man in police uniform while standing atop a tall box, waving her white scarf at passers by.[63] On 8 March 2018, another video went viral, this one of three hijab-less Iranian women singing a feminist fight song in honor of International Women's Day and feminist issues in Tehran's subway .[64]

That same day, in response to the peaceful hijab protests, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, posted a series of tweets ,[65] defending the Islamic state's dress code, praising Islam for keeping women "modest" and in their "defined roles" such as educators and mothers, and chastising Western immodesty.[66] "The features of today's Iranian woman include modesty, chastity, eminence, protecting herself from abuse by men."[67]

Protest, Mahsa Amini

In 2021 a hard-line "Principalist", Ebrahim Raisi, was elected President of Iran, and enforcement of hijab regulations intensified.[68] September 2022, when new and more intense protests followed the killing of Mahsa Amini 22, while in the custody of the morality police after being arrested for "improper hijab".

As of April 2023 protests have fizzled out thanks to a violent crackdown, mass arrests and several executions, but obedience to mandatory hijab by younger women has also dropped markedly, despite harsh penalties. In the capital city of Tehran, it can still be observed in the Bazaar (home of tradition), but not "in places popular with younger women"—parks, cafes, restaurants and malls.[5]

Farnaz Fassihi of the New York Times quotes a 23 year old a graduate student in Sanandaj, in western Iran, "I have not worn a scarf for months ... Whether the government likes to admit it or not, the era of the forced hijab is over."[5]

Even many religious women who wear a hijab by choice have joined the campaign to repeal the law. A petition with thousands of names and photographs of women is circulating on Instagram and Twitter with the message, “I wear the hijab, but I am against the compulsory hijab.”[5]

However, as of 1 April 2023, there has been "unyielding rhetoric" from the Iranian Interior Ministry and head of the judiciary, promising "no retreat or tolerance" on enforcement of mandatory hijab.[6] and two weeks prior Iranian authorities proposed new measures to enforce hijab, replacing Guidance Patrols with surveillance cameras. These

will be used to monitor public spaces for women not wearing the hijab, and offenders will be punished subsequently with measures that include cutting off their mobile phone and Internet connections. Police and judicial authorities will be tasked with collecting evidence and identifying violators.[69]

See also

References

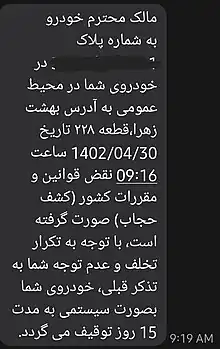

- ↑ "نحوه ارسال پیامک درصورت کشف حجاب در خودرو". خبرگزاری مهر | اخبار ایران و جهان | Mehr News Agency (in Persian). 18 April 2023. Archived from the original on 22 July 2023. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ↑ "Explained: Why the hijab is crucial to Iran's Islamic rulers". euronews. 18 July 2023. Retrieved 4 November 2023.

- ↑ Ramezani, Reza (2010). Hijab dar Iran az Enqelab-e Eslami ta payan Jang-e Tahmili [Hijab in Iran from the Islamic Revolution to the end of the Imposed war] (Persian), Faslnamah-e Takhassusi-ye Banuvan-e Shi’ah [Quarterly Journal of Shiite Women], Qom: Muassasah-e Shi’ah Shinasi, ISSN 1735-4730

- 1 2 3 4 Milani, Farzaneh (1992). Veils and Words: The Emerging Voices of Iranian Women Writers, Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, p. 19, 34–37, ISBN 9780815602668

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Fassihi, Farnaz (25 February 2023). "Their Hair Long and Flowing or in Ponytails, Women in Iran Flaunt Their Locks". The New York Times. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- 1 2 Usher, Sebastian (1 April 2023). "Iran signals determination to enforce hijab rules". BBC News. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ↑ "وزارت صمت: تولیدکنندگان لباسهای باحجاب و کالاهای فرهنگی از پرداخت مالیات معاف هستند". ایران اینترنشنال (in Persian). 15 August 2023. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- ↑ "رونمایی «اعتماد» از پیشنهادات اصلاحی برای لایحه «عفاف و حجاب»؛ از چادر اجباری تا مجازات والدین".

- ↑ "شهر حجاب در تهران و اصفهان احداث میشود". اعتمادآنلاین. 30 October 2023.

- ↑ "'Gender apartheid': UN experts denounce Iran's proposed hijab law". 2 September 2023.

- ↑ "Mobile App Designed by Iranian Regime for Reporting Unveiled Women". 30 October 2023.

- ↑ "شیوهنامه اجرایی عجیب پوشش دانشجویان علومپزشکی؛ از ممنوعیت استفاده از ادکلن تا تفکیک جنسیتی در کلاسهای درس و رعایت حدود شرعی در نگاه به نامحرم!". اعتمادآنلاین. 30 October 2023.

- ↑ "عکس| اقدام بیسابقه عوامل زاکانی برای تفکیک جنسیتی در مترو: بین واگن زنان و مردان جوشکاری شد".

- ↑ "نماینده خامنهای مخالفتها با حجاب اجباری را به فروریختن دیوار برلین تشبیه کرد". BBC News فارسی.

- ↑ "دیدهشدن پایینتر از گردن یا بالاتر از مچ یا ساعد مصایق «بدپوششی» برای زنان؛ تعریف «بدپوششی» برای مردان در قانون حجاب چیست؟". اعتمادآنلاین. 30 October 2023.

- 1 2 El Guindi, Fadwa (1999). Veil: Modesty, Privacy and Resistance, Oxford; New York: Berg Publishers; Bloomsbury Academic, p. 3, 13–16, 130, 174–176, ISBN 9781859739242

- 1 2 3 4 5 Foran, John (2003). Theorizing revolutions. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-77921-5. Archived from the original on 3 December 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ↑ Paidar, Parvin (1995). Women and the political process in twentieth-century Iran. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. pp. 213–215. ISBN 0-521-47340-3. OCLC 30400577. Archived from the original on 1 August 2023. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Why Iranian authorities force women to wear a veil". DW. 21 December 2020. Archived from the original on 8 November 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- 1 2 Vakil, Sanam (2011). Women and politics in the Islamic republic of Iran: Action and reaction. New York: Continnuum-3PL. ISBN 978-1441197344. Archived from the original on 3 December 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ↑ Algar, Hamid (2001). Roots of the Islamic Revolution in Iran: Four Lectures, Oneonta, New York: Islamic Publications International (IPI), p. 84, ISBN 9781889999265

- ↑ Justice for Iran (March 2014). Thirty-five Years of Forced Hijab: The Widespread and Systematic Violation of Women's Rights in Iran (PDF) (Report). www.Justiceforiran.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ↑ "638". Book #5 of the Islamic Penal Code (Sanctions and deterrent penalties) (in Persian).

- ↑ "The Islamic Penal Code of Iran, Book 5". Archived from the original on 17 August 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ↑ "Iran signals determination to enforce hijab rules". BBC News. 1 April 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ↑ "Iran establishes new base to enforce mandatory hijab". 24 May 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ↑ "Why is Iran bringing back its 'morality police'? – DW – 07/17/2023". dw.com. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ↑ "Iran establishes new base to enforce mandatory hijab". 24 May 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ↑ "Iran mullahs enforce compulsory Hijab via new "bases" and repressive laws - NCRI Women Committee". 17 June 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ↑ "irans-provincial-authorities-determined-to-enforce-hijab-rules".

- ↑ "Iran signals determination to enforce hijab rules". BBC News. 1 April 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ↑ "Iran mullahs enforce compulsory Hijab via new "bases" and repressive laws - NCRI Women Committee". 17 June 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ↑ "irans-provincial-authorities-determined-to-enforce-hijab-rules".

- ↑ "Iran establishes new base to enforce mandatory hijab". 24 May 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ↑ "Iran mullahs enforce compulsory Hijab via new "bases" and repressive laws - NCRI Women Committee". 17 June 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ↑ "عضو مجلس ایران خواستار محرومیت «بیحجابها» از خدمات اجتماعی شد". العربیه فارسی. 4 February 2023.

- ↑ "۱۵ طرح در طول چهار ماه با هدف کنترل و برخورد با اعتراض ها". دیدبان ایران. 16 August 2023.

- ↑ Luyken, Jörg (7 August 2023). "German-made cameras used to catch Iranian women defying hijab ban". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- ↑ "Germany's Bosch aided Iran's efforts targeting anti-hijab women and protesters: Report". WION. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- ↑ "جزئیاتی جدید از لایحه « عفاف و حجاب»؛ زنان، مرتبطین با رسانهها و کسبه در معرض اتهام". 26 July 2023. Archived from the original on 26 July 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ↑ "جبار برای پوشش متحدالشکل مقنعه و مانتو در فستفودهای مشهد". اعتمادآنلاین. 16 August 2023.

- ↑ "نماینده اصفهان: برای مقابله با بیحجابی، جریمه مستقیما از حساب افراد بیحجاب کسر میشود". ایران اینترنشنال (in Persian). 2 August 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ↑ "ندادن خدمات پزشکی به افراد بیحجاب رسما اعلام جنگ علیه قانون است؛ برای نظام حکمرانی هم بسیار خطرناک است". Archived from the original on 1 August 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ↑ "حجاب اجباری در ایران؛ تقلاهای حکومت و ادامه مقاومت زنان – DW – ۱۴۰۲/۵/۱۶". dw.com.

- ↑ "نماینده رفسنجان: بیحجابان زیر ۱۸ سال از تحصیل، پاسپورت و اینترنت محروم میشوند". ایران اینترنشنال. 16 August 2023.

- ↑ "Iran's politicians to debate hijab laws in secret". BBC. 13 August 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ↑ رویداد۲۴, پايگاه خبری تحلیلی (1 August 2023). "جریمههای لایحه حجاب و عفاف چقدر برای دولت درآمد دارد؟ +جدول | رویداد24". fa (in Persian). Retrieved 8 August 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "مجازات کشفحجابکننده غیرایرانی در قانون حجاب و عفاف چیست؟". اعتمادآنلاین (in Persian). 24 September 2023. Retrieved 24 September 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 "How to dress in Iran: a guide from head to toe". Easy Iran. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- 1 2 "The 'Girls of Revolution Street' Protest Iran's Compulsory Hijab Laws · Global Voices". Global Voices. 30 January 2018. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- 1 2 Kasana, Mehreen. "Why This One Video of a Woman Protesting in Iran Is Going Viral". Bustle. Archived from the original on 12 March 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ↑ "On Wednesday we wear white: Women in Iran challenge compulsory hijab". Newsweek. 14 June 2017. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ↑ "The high stakes of hijab protests in Iran". Axios. 17 February 2018. Archived from the original on 17 December 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Gerretsen, Isabelle (1 February 2018). "Iran: 29 women arrested over anti-hijab protests inspired by 'girl of Enghelab Street'". International Business Times UK. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ↑ "Vida Movahed, the woman who sparked anti-hijab protests in Iran | The Arab Weekly". The Arab Weekly. Archived from the original on 12 March 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ↑ Hatam, Nassim (14 June 2017). "Why Iranian women are wearing white on Wednesdays". BBC News. Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ↑ "Nasrin Sotoudeh نسرین ستوده". www.facebook.com. Archived from the original on 25 July 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ↑ "Iran lawyer raises concern over missing hijab protester". The Daily Star Newspaper – Lebanon. 22 January 2018. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ↑ "Iranian Police Arrest 29 Women Protesting Against Veiling Law". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- 1 2 "Iran: Dozens of women ill-treated and at risk of long jail terms for peacefully protesting compulsory veiling". www.amnesty.org. 26 February 2018. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ↑ "Iran Human Rights Documentation Center – Islamic Penal Code of the Islamic Republic of Iran – Book Five". www.iranhrdc.org. Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ↑ "Woman Who Removed Headscarf in Public Sentenced to Prison as Supreme Leader Tries to Diminish Hijab Protests – Center for Human Rights in Iran". www.iranhumanrights.org. 10 March 2018. Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ↑ "Iran Chides Police for Using Force Against Female Veil Protester". Bloomberg.com. 25 February 2018. Archived from the original on 13 March 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ↑ Esfandiari, Golnaz. "Feminist Trio Takes Defiant Song To Tehran's Subway, Video Goes Viral". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ↑ "Khamenei Claims Iran's 'Enemies' Behind Anti-Hijab Protests". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ↑ Cunningham, Erin (8 March 2018). "Iran's supreme leader in tweetstorm: Western countries lead women to 'deviant lifestyle'". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ↑ "Khamenei.ir (@khamenei_ir) | Twitter". twitter.com. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ↑ Krauss, Joseph (21 September 2022). "EXPLAINER: What kept Iran protests going after first spark?". AP NEWS. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ↑ "Iranian Government Proposes New Measures To Enforce Hijab Law, Including Surveillance". RFE/RL. 15 March 2023. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2023.