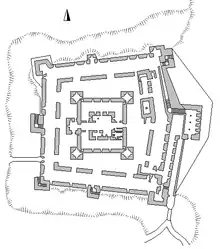

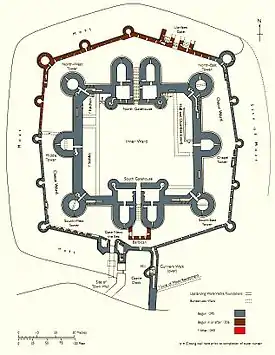

A concentric castle is a castle with two or more concentric curtain walls, such that the outer wall is lower than the inner and can be defended from it.[1] The layout was square (at Belvoir and Beaumaris) where the terrain permitted, or an irregular polygon (at Krak and Margat) where curtain walls of a spur castle followed the contours of a hill.

Concentric castles resemble one castle nested inside the other, thus creating an inner and outer ward. They are typically built without a central free-standing keep. Where the castle includes a particularly strong tower (donjon), such as at Krak or Margat, it projects from the inner enceinte.

Development

Surrounding fortresses or towns with a series of defensive walls where the outer walls are lower than the inner walls is something that has been found in fortifications going back thousands of years to cultures like the Assyrians, Persians, Ancient Egyptians and Babylonians. The ancient city of Lachish, a place in Israel, was excavated and found to consist of multiple walls that were illustrated in Assyrian art documenting their successful siege of the city. The Byzantines also famously constructed the Walls of Constantinople, which featured double layers of walls through most of its perimeter and a moat. The city of ancient Babylon also featured multiple layers of fortifications, famously seen in the Ishtar Gate. However, the relationship of the concentric castle to other forms of fortification is complex. An example of an early concentric castle is the Byzantine castle of Korykos in Turkey, built in the early 11th century AD.[2]

Historians (in particular Hugh Kennedy) have argued that the concentric defence arose as a response to advances in siege technology in the crusader states from the 12th to the 13th century. The outer wall protected the inner one from siege engines, while the inner wall and the projecting towers provided flanking fire from crossbows. Also, the strong towers may have served as platforms for trebuchets for shooting back at the besiegers. The walls typically include towers, arrowslits, and wall-head defences such as crenellation and, in more advanced cases, machicolations, all aimed at an active style of defence.[1] The Krak des Chevaliers in Syria is the best-preserved of the concentric crusader castles. By contrast, Château Pèlerin was not a concentric castle, as the side facing the sea did not require defensive walls. However, the two walls facing the land are built on the same defensive principles as other crusader castles in the same period, rivalling the defences at Krak.

While a concentric castle has double walls and towers on all sides, the defences need not be uniform in all directions. There can still be a concentration of defences at a vulnerable point. At Krak des Chevaliers, this is the case at the southern side, where the terrain permits an attacker to deploy siege engines. Also, the gate and posterns are typically strengthened using a bent entrance or flanking towers.

Concentric castles were expensive to build, so that only the powerful military orders, the Hospitallers and Templars, or powerful kings could afford to build and maintain them. It has also been pointed out that the concentric layout suited the requirements of military orders such as the Hospitallers in resembling a monastery and housing a large garrison. Such castles were beyond the means of feudal barons. Thus, concentric castles coexisted with simpler enclosure castles and tower keeps even in the crusader states.[3]

Concentric castles appeared in Europe in the 13th century, with the castles built in Wales by Edward I providing some outstanding examples, in particular Beaumaris Castle, a "perfect concentric castle",[4] albeit unfinished. As Beaumaris was built on flat terrain rather than a spur, it was both necessary and possible to build walls and towers facing in all directions, giving a very regular, almost square, floor plan to the castle. Some influence from crusader fortification has been conjectured, but the amount of technology transfer from the East and much earlier Byzantine examples remains controversial among historians.[1]

Similar structures

In the German-speaking states of the Holy Roman Empire, many castles had double curtain walls with a narrow ward between them, referred to as a Zwinger. These were added at vulnerable points like the gate but were rarely as fully developed as in the concentric castles in Wales or the Crusader castles.

The principle of an outer and inner wall was also used in fortified cities, such as the Theodosian Walls of Constantinople and the city wall of Carcassonne.

The concept of mutually reinforcing lines of defence with flanking fire was continued in later periods, such as the early modern fortifications of Vauban, where outer defence works were protected and overlooked by others and their capture did not destroy the integrity of the inner Citadel.

Citadels from before and during the Reconquista in Spain and Portugal also have fortifications similar to concentric castles found elsewhere in Europe. Castle of Almodóvar del Río is a good example of such a fortress along with Saint George Castle in Lisbon Portugal.

Examples of concentric castles

Castle of Margat (Syria), 1062–

Castle of Margat (Syria), 1062– Belvoir Castle (Israel), 1150

Belvoir Castle (Israel), 1150 Münzenberg Castle (Hesse), 1162

Münzenberg Castle (Hesse), 1162 Kidwelly Castle, south-west Wales, 13th century

Kidwelly Castle, south-west Wales, 13th century Rhuddlan Castle, north of Wales, 1277

Rhuddlan Castle, north of Wales, 1277 Harlech Castle, west of Wales, 1282–

Harlech Castle, west of Wales, 1282– Beaumaris Castle, on the island of Anglesey at the north-west of Wales, 1295

Beaumaris Castle, on the island of Anglesey at the north-west of Wales, 1295 The Byzantine castle of Korykos from the sea c.11th cent. AD. It featured fully concentric features a century before the first examples of concentric fortifications were seen in the West

The Byzantine castle of Korykos from the sea c.11th cent. AD. It featured fully concentric features a century before the first examples of concentric fortifications were seen in the West Caerphilly Castle, south of Wales, 13th century

Caerphilly Castle, south of Wales, 13th century

See also

- Buhen (ancient Egyptian stronghold)

References

- 1 2 3 Kennedy, Hugh (2000). Crusader Castles. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-79913-9.

- ↑ Foss, Clive (1986). Byzantine fortifications an introduction. Univ. of South Africa. ISBN 0869813218. OCLC 254999395.

- ↑ Nicolle, David (2008). Crusader Castles in the Holy Land: An Illustrated History of the Crusader Fortifications of the Middle East and Mediterranean. ISBN 978-1846033490.

- ↑ Reginald Allen Brown (1989). Castles from the air. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-32932-3.