| Coracoid process | |

|---|---|

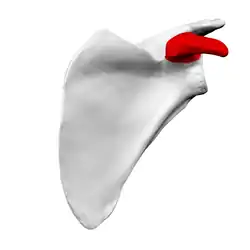

Left scapula. Anterior view. Coracoid process shown in red. | |

Anterior view. Coracoid process shown in red. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Processus coracoideus |

| MeSH | D000070597 |

| TA98 | A02.4.01.023 |

| TA2 | 1159 |

| FMA | 13455 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The coracoid process (from Greek κόραξ, raven[1]) is a small hook-like structure on the lateral edge of the superior anterior portion of the scapula (hence: coracoid, or "like a raven's beak"). Pointing laterally forward, it, together with the acromion, serves to stabilize the shoulder joint. It is palpable in the deltopectoral groove between the deltoid and pectoralis major muscles.

Structure

The coracoid process is a thick curved process attached by a broad base to the upper part of the neck of the scapula; it runs at first upward and medially; then, becoming smaller, it changes its direction, and projects forward and laterally.

The component parts of the process are the base; angle; shaft; and apex of the coracoid process, respectively. The coracoglenoid notch is an indentation localized between the coracoid process and the glenoid. As the coracoid process projects laterally, it defines the subcoracoid space beneath. [2]

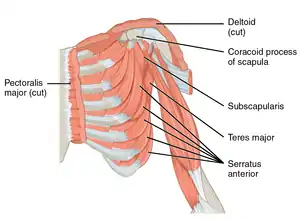

The ascending portion, flattened from the frontal aspect backward, presents in front a smooth concave surface, across which the subscapularis passes.

The horizontal portion appears flattened when viewed from above looking downward; its upper surface is convex and irregular, and gives attachment to the pectoralis minor; its under surface is smooth; its medial and lateral borders are rough; the former gives attachment to the pectoralis minor and the latter to the coracoacromial ligament; the apex is embraced by the Conjoint tendon of origin of the coracobrachialis and short head of the biceps brachii and gives attachment to the coracoclavicular fascia.

On the medial part of the root of the coracoid process is a rough impression for the attachment of the conoid ligament; and running from it obliquely forward and laterally, on to the upper surface of the horizontal portion, is an elevated ridge for the attachment of the trapezoid ligament.[3]

The coracoid process is a snare molded bone design projecting anterolaterally from the unrivaled(?) part of the scapular neck. Surgeons refer to this part of the body as the “lighthouse of the shoulder”[4] as it is close to the area where structures of veins and nerves (neurovascular) are bound together. The distances between the coracoid base and the neurovascular structures is like a 90 degree chair. The suprascapular ligament is right next to the coracoid process. The muscles that are attached are: Pectoralis Minor, Coracobrachialis, and Biceps Brachii.

In addition, this structure attaches all the tendons and ligaments together. There are two purposes for this structure: it is the primary hold by which the clavicle is joined to the scapula and alongside the acromion and coraco-acromial tendon, it shapes the curve over the glenoid. By having the coracoid process, this allows the scapula to not be attached to the skeletons by the bone so that it can only support the limbs. Although there are minor instances where the coracoid process can be damaged by itself, there can still be damage to the structure with an acute subscapularis tear. Usually a disruption in the coracoid process can indicate a shoulder injury such as dislocation and instability.

Attachments

It is the site of attachment for several structures:

Muscles

- The pectoralis minor muscle (insertion) – to 3rd, 4th, 5th and on some rare occasions, 6th rib.

- The short head of biceps brachii muscle (origin) – to radial tuberosity.

- The coracobrachialis muscle (origin) – to medial humerus.

Ligaments

- The coracoclavicular ligament – to the clavicle. (The ligament is formed by the conoid ligament and trapezoid ligament.)

- The coracoacromial ligament – to the acromion

- The coracohumeral ligament – to the humerus

- The superior transverse scapular ligament – from the base of the coracoid to the medial portion of the suprascapular notch

Clinical significance

The coracoid process is palpable just below the lateral end of the clavicle (collar bone). It is otherwise known as the "Surgeon's Lighthouse" because it serves as a landmark to avoid neurovascular damage.[5] Major neurovascular structures enter the upper limb medial to the coracoid process, so that surgical approaches to the shoulder region should always take place laterally to the coracoid process.

Other animals

In monotremes, the coracoid is a separate bone. Reptiles, birds, and frogs (but not salamanders) also possess a bone by this name, but is not homologous with the coracoid process of mammals.[6]

Analyses of the size and shape of the coracoid process in Australopithecus africanus (STS 7) have shown that, in this species, it displayed a prominent dorsolateral tubercle placed more laterally than in modern humans. This may reflect, according to one interpretation, a scapula positioned high on a funnel-shaped thorax with an obliquely-positioned clavicle, as in extant non-human great apes. [7]

Anthropologists examine the coracoid process when studying shoulder morphology to determine whether the upper limbs provided support for bipedalism in the early hominin ages.[8] The shoulder is an area of primate life structures that previous examinations have demonstrated to emphatically mirror the varying useful requests forced by contrasts in locomotor modes. Since the morphology of early hominin upper appendage components comprises a blend of derived traits, it is noted that these primitive features are of continuous usage throughout the evolution of hominins. When Australopithecus africanus (known as Sts 7 within the realms of Anthropology) was being examined, it was observed that the scapular orientation was higher as compared to modern day humans (Homo sapiens). However, Homo Sapiens do not have distinct features in terms of shape or size when it comes to the coracoid process.[9] Within the research of Elizabeth Vrbua, a paleoanthropologist who made a study called “A New Study of the Scapula of Australopithecus africanus from Sterkfontein”, it was seen that A. africanus had a higher scapular position which could infer that this position is likely to be seen in earlier hominins as well.[10]

According to the authors of “The human acromion viewed from an evolutionary perspective”, there were different shapes of surface of the coracoid process within the various hominins.[11] The gorillas had a wide shape, chimpanzees, orangutans and humans had an intermediate shape, and the gibbon had a small shape. This can further be analyzed as the different hominids have variability in their shape of the coracoid process. The latest contributions to the evolutionary coracoid process were from Doctor M. Hussan in 2016 where he added further insight on the significance of the subacromial impingement and coracoacromial arch’s importance with the aid of pathology.

Additional images

Left scapula. Coracoid process shown in red.

Left scapula. Coracoid process shown in red. Animation. Coracoid process shown in red.

Animation. Coracoid process shown in red. Left scapula. Lateral view. Coracoid process shown in red.

Left scapula. Lateral view. Coracoid process shown in red.

References

- ↑ Liddell, Scott, Jones Ancient Greek Lexicon (LSJ)

- ↑ Al-Redouan, Azzat; Kachlik, David (2022). "Scapula revisited: new features identified and denoted by terms using consensus method of Delphi and taxonomy panel to be implemented in radiologic and surgical practice". J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 31 (2): e68–e81. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2021.07.020. PMID 34454038. S2CID 237348158.

- ↑ Gray's Anatomy (1918), see infobox.

- ↑ Mohammed, Hussan; Skalski, Matthew R.; Patel, Dakshesh B.; Tomasian, Anderanik; Schein, Aaron J.; White, Eric A.; Hatch, George F. Rick; Matcuk, George R. (November 2016). "Coracoid Process: The Lighthouse of the Shoulder". RadioGraphics. 36 (7): 2084–2101. doi:10.1148/rg.2016160039. ISSN 0271-5333. PMID 27471875.

- ↑ Gallino, Mario; Santamaria, Eliana; Tiziana, Doro (1998). "Anthropometry of the scapula: Clinical and surgical considerations". Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 7 (3): 284–291. doi:10.1016/S1058-2746(98)90057-X. PMID 9658354.

"...defined by Matsen et al. as 'the lighthouse of the shoulder.'

- Matsen, Frederick A; Lippitt, Steven B; Sidles, John A; Douglas T, Harryman (1984). Practical Evaluation and Management of the Shoulder. Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-4819-4.

- ↑ Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 186–187. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ↑ Larson, Susan G. (2009). "Evolution of the Hominin Shoulder: Early Homo". In Grine, Frederick E.; Fleagle, John G.; Leakey, Richard E. (eds.). The First Humans - Origin and Early Evolution of the Genus Homo. Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology. Springer. pp. 65–6. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9980-9. ISBN 978-1-4020-9979-3.

- ↑ Larson, Susan (2013-03-16), "Shoulder Morphology in Early Hominin Evolution", The Paleobiology of Australopithecus, pp. 247–261, ISBN 978-94-007-5918-3, retrieved 2022-03-04

- ↑ Martin, C. P.; O'brien, H. D. (July 1939). "The coracoid process in the primates". Journal of Anatomy. 73 (Pt 4): 630–642. ISSN 0021-8782. PMC 1252469. PMID 17104786.

- ↑ Vrba, Elizabeth (1979). "A New Study of the Scapula of Australopithecus africanus from Sterkfontein". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 51: 117–129. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330510114.

- ↑ Voisin, J-L (2014). "The human acromion viewed from an evolutionary perspective". Orthopaedics & Traumatology, Surgery & Research. 100 (8 Suppl): S355-60. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2014.09.011. PMID 25454328.

External links

- Anatomy image: skel/scapula2 at Human Anatomy Lecture (Biology 129), Pennsylvania State University

- Coracoid Process - BlueLink Anatomy, University of Michigan Medical School