| Arcus senilis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | arcus adiposus, arcus juvenilis, arcus lipoides corneae, arcus cornealis |

| |

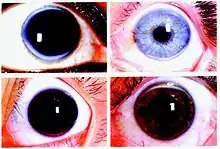

| Arcus senilis deposits tend to start at 6 and 12 o'clock and progress until becoming completely circumferential. The thin clear section separating the arcus from the limbus is known as the clear interval of Vogt. | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

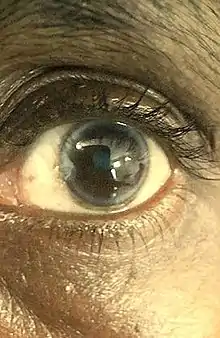

| Symptoms | Opaque ring in the peripheral cornea |

| Causes | Normal aging, Hyperlipidemia |

| Differential diagnosis | Limbus sign, limbal ring |

| Treatment | None |

| Prognosis | Benign condition in elderly, associated with cardiovascular disease for <50 yrs old |

Arcus senilis (AS), also known as gerontoxon, arcus lipoides, arcus corneae, corneal arcus, arcus adiposus, or arcus cornealis, are rings in the peripheral cornea. It is usually caused by cholesterol deposits, so it may be a sign of high cholesterol. It is the most common peripheral corneal opacity, and is usually found in the elderly where it is considered a benign condition. When AS is found in patients less than 50 years old it is termed arcus juvenilis. The finding of arcus juvenilis in combination with hyperlipidemia in younger men represents an increased risk for cardiovascular disease.

Pathophysiology

AS is caused by leakage of lipoproteins from limbal capillaries into the corneal stroma. Deposits have been found to consist mostly of low-density lipoprotein (LDL). Deposition of lipids into the cornea begins at the superior and inferior aspects, and progresses to encircle the entire peripheral cornea. The interior border of AS has a diffuse appearance, while the exterior border is well demarcated. The clear space between the exterior border and the limbus is called the interval of Vogt.[1]

Bilateral AS is a benign finding in the elderly, but it can be associated with hyperlipidemia in patients less than 50 years old. Bilateral AS may also be caused by increased levels of free fatty acids in the circulation secondary to alcohol use.[2]

Unilateral AS can be associated with contralateral carotid artery stenosis or decreased intraocular pressure in the affected eye. As these are serious medical conditions, unilateral AS should be examined by a physician.[3]

Diagnosis

AS is usually diagnosed through visual inspection by an ophthalmologist or optometrist using a slit lamp.

Differential diagnoses

Several conditions can have a similar color and appearance.

- Limbus sign is caused by dystrophic calcification at the corneal limbus, and can be confused with AS in geriatric populations.[4]

- Anterior embryotoxon is a congenital widening of the corneal limbus.[1]

- Posterior embryotoxon is a congenital thickening and anterior displacement of schwalbe's line.[1]

Other conditions with similar appearance, but differing in color are limbal ring, and Kayser–Fleischer ring.

Treatment

In the elderly, arcus senilis is a benign condition that does not require treatment. The presence of an arcus senilis in males under the age of 50 may represent a risk factor for cardiovascular disease,[5] and these individuals should be screened for an underlying lipid disorder. The opaque ring in the cornea does not resolve with treatment of a causative disease process, and can create cosmetic concerns.[5]

Epidemiology

In men, AS is increasingly found starting at age 40, and is present in nearly 100% of men over the age of 80. For women, onset of AS begins at age 50 and is present in nearly all females by age 90.[1]

Risk factor for cardiovascular disease

AS is not an independent predictor of cardiovascular disease, as demonstrated by a prospective cohort study of 12,745 Danes aged 20-93 followed up for an average of 22 years.[6]

The presence of AS in men less than 50 years old(arcus juvenilis) in combination with an underlying condition causing hyperlipidemia has been shown to significantly increase the relative risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease and coronary artery disease, as demonstrated by a study following 6,069 Americans aged 30-69 for an average of 8.4 years.[7]

The presence of AS in men less than 50 years old (arcus juvenilis) in conjunction with xanthomas on the achilles tendon has been linked to the presence of atherosclerosis in the coronary arteries and aorta by computed tomography.[8]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Duker JS, Yanof M (2013-12-16). Ophthalmology: Expert Consult: Online and Print. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-4557-3984-4.

- ↑ Hickey N, Maurer B, Mulcahy R (July 1970). "Arcus senilis: its relation to certain attributes and risk factors in patients with coronary heart disease". British Heart Journal. 32 (4): 449–52. doi:10.1136/hrt.32.4.449. PMC 487351. PMID 5433305.

- ↑ Naumann GO, Küchle M (November 1993). "Unilateral corneal arcus lipoides". Lancet. 342 (8880): 1185. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(93)92170-x. PMID 7901520. S2CID 5395741.

- ↑ Williams ME (2010-06-21). Geriatric Physical Diagnosis: A Guide to Observation and Assessment. McFarland. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-7864-5160-9.

- 1 2 Munjal A, Kaufman EJ (2021). "Arcus Senilis". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32119257. Retrieved 2021-03-23.

- ↑ Christoffersen M, Frikke-Schmidt R, Schnohr P, Jensen GB, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjærg-Hansen A (September 2011). "Xanthelasmata, arcus corneae, and ischaemic vascular disease and death in general population: prospective cohort study". BMJ. 343: d5497. doi:10.1136/bmj.d5497. PMC 3174271. PMID 21920887.

- ↑ Chambless LE, Fuchs FD, Linn S, Kritchevsky SB, Larosa JC, Segal P, Rifkind BM (October 1990). "The association of corneal arcus with coronary heart disease and cardiovascular disease mortality in the Lipid Research Clinics Mortality Follow-up Study". American Journal of Public Health. 80 (10): 1200–4. doi:10.2105/ajph.80.10.1200. PMC 1404822. PMID 2400030.

- ↑ Zech LA, Hoeg JM (March 2008). "Correlating corneal arcus with atherosclerosis in familial hypercholesterolemia". Lipids in Health and Disease. 7: 7. doi:10.1186/1476-511X-7-7. PMC 2279133. PMID 18331643.