| Corneal dystrophy | |

|---|---|

| |

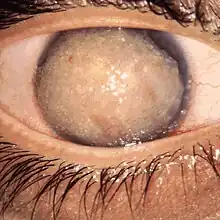

| Corneal dystrophy, Gelatinous drop-like | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

Corneal dystrophy is a group of rare hereditary disorders characterised by bilateral abnormal deposition of substances in the transparent front part of the eye called the cornea.[1][2][3]

Signs and symptoms

Corneal dystrophy may not significantly affect vision in the early stages. However, it does require proper evaluation and treatment for restoration of optimal vision. Corneal dystrophies usually manifest themselves during the first or second decade but sometimes later. It appears as grayish white lines, circles, or clouding of the cornea. Corneal dystrophy can also have a crystalline appearance.

There are over 20 corneal dystrophies that affect all parts of the cornea. These diseases share many traits:

- They are usually inherited.

- They affect the right and left eyes equally.

- They are not caused by outside factors, such as injury or diet.

- Most progress gradually.

- Most usually begin in one of the five corneal layers and may later spread to nearby layers.

- Most do not affect other parts of the body, nor are they related to diseases affecting other parts of the eye or body.

- Most can occur in otherwise totally healthy people, male or female.

Corneal dystrophies affect vision in widely differing ways. Some cause severe visual impairment, while a few cause no vision problems and are diagnosed during a specialized eye examination by an ophthalmologist. Other dystrophies may cause repeated episodes of pain without leading to permanent loss of vision.[4]

Genetics

Different corneal dystrophies are caused by mutations in the CHST6, KRT3, KRT12, PIP5K3, SLC4A11, TACSTD2, TGFBI, and UBIAD1 genes. Mutations in TGFBI which encodes transforming growth factor beta induced cause several forms of corneal dystrophies including granular corneal dystrophy, lattice corneal dystrophy, epithelial basement membrane dystrophy, Reis-Bucklers corneal dystrophy, and Thiel–Behnke dystrophy.

Corneal dystrophies may have a simple autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive or rarely X-linked recessive Mendelian mode of inheritance:

| Name | Inheritance | Gene locus | Gene |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superficial corneal dystrophies | |||

| Meesmann corneal dystrophy | AD | 12q13, 17q12 | KRT3, KRT12 |

| Reis-Bücklers corneal dystrophy | AD | 5q31 | TGFBI |

| Gelatinous drop-like corneal dystrophy | AR | 1p32 | TACSTD2 |

| Stromal corneal dystrophies | |||

| Macular dystrophy | AR | 16q22 | CHST6 |

| Granular dystrophy | AD | 5q31 | TGFBI |

| Lattice dystrophy | AD | 5q31, 9q34 | TGFBI, GSN (gene) |

| Schnyder corneal dystrophy | AD | 1p34.1–p36 | UBIAD1 |

| Congenital stromal corneal dystrophy | AD | 12q13.2 | DCN |

| Fleck corneal dystrophy | AD | 2q35 | PIP5K3 |

| Posterior dystrophies | |||

| Fuchs' dystrophy | AD | 1p34.3,13pTel-13q12.13, 18q21.2–q21.32, 20p13-p12, 10p11.2 | COL8A, SLC4A11, TCF8, TCF4 |

| Posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy | AD | 20p11.2, 1p34.3-p32.3, 10p11.2 | COL8A2, TCF8,OVOL2, GRHL2 |

| Congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy | AR | 20p13-p12 | SLC4A11 |

Pathophysiology

A corneal dystrophy can be caused by an accumulation of extraneous material in the cornea, including lipids and cholesterol crystals.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis can be established on clinical grounds and this may be enhanced with studies on surgically excised corneal tissue and in some cases with molecular genetic analyses. As clinical manifestations widely vary with the different entities, corneal dystrophies should be suspected when corneal transparency is lost or corneal opacities occur spontaneously, particularly in both corneas, and especially in the presence of a positive family history or in the offspring of consanguineous parents.

Superficial corneal dystrophies – Meesmann dystrophy is characterized by distinct tiny bubble-like, punctate opacities that form in the central corneal epithelium and to a lesser extent in the peripheral cornea of both eyes during infancy that persists throughout life. Symmetrical reticular opacities form in the superficial central cornea of both eyes at about 4–5 years of age in Reis-Bücklers corneal dystrophy. Patient remains asymptomatic until epithelial erosions precipitate acute episodes of ocular hyperemia, pain, and photophobia. Visual acuity eventually becomes reduced during the second and third decades of life following a progressive superficial haze and an irregular corneal surface. In Thiel–Behnke dystrophy, sub-epithelial corneal opacities form a honeycomb-shaped pattern in the superficial cornea. Multiple prominent gelatinous mulberry-shaped nodules form beneath the corneal epithelium during the first decade of life in gelatinous drop-like corneal dystrophy which cause photophobia, tearing, corneal foreign body sensation and severe progressive loss of vision. Lisch epithelial corneal dystrophy is characterized by feather shaped opacities and microcysts in the corneal epithelium that are arranged in a band-shaped and sometimes whorled pattern. Painless blurred vision sometimes begins after sixty years of life.

Corneal stromal dystrophies – Macular corneal dystrophy is manifested by a progressive dense cloudiness of the entire corneal stroma that usually first appears during adolescence and eventually causing severe visual impairment. In granular corneal dystrophy multiple small white discrete irregular spots that resemble bread crumbs or snowflakes become apparent beneath Bowman zone in the superficial central corneal stroma. They initially appear within the first decade of life. Visual acuity is more or less normal. Lattice dystrophy starts as fine branching linear opacities in Bowman's layer in the central area and spreads to the periphery. Recurrent corneal erosions may occur. The hallmark of Schnyder corneal dystrophy is the accumulation of crystals within the corneal stroma which cause corneal clouding typically in a ring-shaped fashion.

Posterior corneal dystrophies – Fuchs corneal dystrophy presents during the fifth or sixth decade of life. The characteristic clinical findings are excrescences on a thickened Descemet membrane (cornea guttae), generalized corneal edema and decreased visual acuity. In advanced cases, abnormalities are found in all the layers of the cornea. In posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy small vesicles appear at the level of Descemet membrane. Most patients remain asymptomatic and corneal edema is usually absent. Congenital hereditary endothelial corneal dystrophy is characterized by a diffuse ground-glass appearance of both corneas and markedly thickened (2–3 times thicker than normal) corneas from birth or infancy.

Differential diagnosis

Main differential diagnosis include various causes of monoclonal gammopathy, lecithin-cholesterol-acyltransferase deficiency, Fabry disease, cystinosis, tyrosine transaminase deficiency, systemic lysosomal storage diseases, and several skin diseases (X-linked ichthyosis, keratosis follicularis spinolosa decalvans).

Historically, an accumulation of small gray variable shaped punctate opacities of variable shape in the central deep corneal stroma immediately anterior to Descemet membrane were designated deep filiform dystrophy and cornea farinata because of their resemblance to commas, circles, lines, threads (filiform), flour (farina) or dots. These abnormalities are now known to accompany X-linked ichthyosis, steroid sulfatase deficiency, caused by steroid sulfatase gene mutations and are currently usually not included under the rubric of the corneal dystrophies.

In the past, the designation vortex corneal dystrophy (corneal verticillata) was applied to a corneal disorder characterized by the presence of innumerable tiny brown spots arranged in curved whirlpool-like lines in the superficial cornea. An autosomal dominant mode of transmission was initially suspected, but later it was realized that these individuals were affected hemizygous males and asymptomatic female carriers of an X-linked systemic metabolic disease caused by a deficiency of α-galactosidase, known as Fabry disease.[3]

Classification

Corneal dystrophies were commonly subdivided depending on its specific location within the cornea into anterior, stromal, or posterior according to the layer of the cornea affected by the dystrophy.

In 2015 the ICD3 classification was published.[5] and has classified disease into four groups as follows:

Epithelial and subepithelial dystrophies

- Epithelial basement membrane dystrophy

- Epithelial recurrent erosion dystrophies (Franceschetti corneal dystrophy, Dystrophia Smolandiensis, and Dystrophia Helsinglandica)

- Subepithelial mucinous corneal dystrophy

- Meesmann corneal dystrophy

- Lisch epithelial corneal dystrophy

- Gelatinous drop-like corneal dystrophy

Bowman Layer dystrophies

- Reis–Bücklers corneal dystrophy

- Thiel–Behnke corneal dystrophy

- Stromal dystrophies-

- TGFB1 corneal dystrophies

- Lattice corneal dystrophy, type 1 variants (III, IIIA, I/IIIA, IV) of lattice corneal dystrophy

- Granular corneal dystrophy, type 1

- Granular corneal dystrophy, type 2

Stromal dystrophies

- Macular corneal dystrophy

- Schnyder crystalline corneal dystrophy

- Congenital stromal corneal dystrophy

- Fleck corneal dystrophy

- Posterior amorphous corneal dystrophy

- Central cloudy dystrophy of François

- Pre-Descemet corneal dystrophy

Endothelial dystrophies

- Fuchs' dystrophy

- Posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy

- Congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy

- X-linked endothelial corneal dystrophy

The following (now historic) classification was by Klintworth:[3]

Superficial dystrophies:

- Epithelial basement membrane dystrophy

- Meesmann juvenile epithelial corneal dystrophy

- Gelatinous drop-like corneal dystrophy

- Lisch epithelial corneal dystrophy

- Subepithelial mucinous corneal dystrophy

- Reis-Bucklers corneal dystrophy

- Thiel–Behnke dystrophy

Stromal dystrophies:

- Lattice corneal dystrophy

- Granular corneal dystrophy

- Macular corneal dystrophy

- Schnyder crystalline corneal dystrophy

- Congenital stromal corneal dystrophy

- Fleck corneal dystrophy

Posterior dystrophies:

- Fuchs' dystrophy

- Posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy

- Congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy

Treatment

Early stages may be asymptomatic and may not require any intervention. Initial treatment may include hypertonic eyedrops and ointment to reduce the corneal edema and may offer symptomatic improvement prior to surgical intervention.

Suboptimal vision caused by corneal dystrophy may be helped with scleral contact lenses but eventually usually requires surgical intervention in the form of corneal transplantation. Penetrating keratoplasty, a common type of corneal transplantation, is commonly performed for extensive corneal dystrophy.

With penetrating keratoplasty (corneal transplant), the long-term results are good to excellent. Recent surgical improvements have been made which have increased the success rate for this procedure. However, recurrence of the disease in the donor graft may happen. Superficial corneal dystrophies do not need a penetrating keratoplasty as the deeper corneal tissue is unaffected, therefore a lamellar keratoplasty may be used instead.

Phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK) can be used to excise or ablate the abnormal corneal tissue. Patients with superficial corneal opacities are suitable candidates for this procedure.[3]

See also

References

- ↑ Basic&Clinical Science Course; External disease and cornea (2011-2012 ed.). American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2012. ISBN 9781615251155.

- ↑ Weiss JS, Møller HU, Lisch W, Kinoshita S, Aldave AJ, Belin MW, Kivelä T, Busin M, Munier FL, Seitz B, Sutphin J, Bredrup C, Mannis MJ, Rapuano CJ, Van Rij G, Kim EK, Klintworth GK (December 2008). "The IC3D classification of the corneal dystrophies". Cornea. 27 (Suppl 2): S1–83. doi:10.1097/ICO.0b013e31817780fb. PMC 2866169. PMID 19337156.

- 1 2 3 4 Klintworth GK (2009). "Corneal dystrophies". Orphanet J Rare Dis. 4 (1): 7. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-4-7. PMC 2695576. PMID 19236704.

- ↑ "Facts About the Cornea and Corneal Disease". National Eye Institute. Archived from the original on 2005-03-27.

- ↑ Weis JS (2015). "IC3D Classification of Corneal Dystrophies—Edition 2". Cornea. 34 (2): 117–159. doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000000307. hdl:11392/2380137. PMID 25564336.