| Cornwall Railway | |

|---|---|

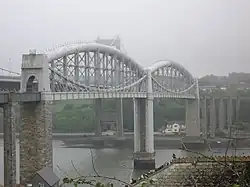

The Royal Albert Bridge that carries the route of the Cornwall Railway across the River Tamar | |

| History | |

| 1835 | Proposal for a railway from London to Falmouth |

| 1839 | Proposal for the Cornwall Railway |

| 1846 | Cornwall Railway Act |

| 1848–52 | Construction suspended |

| 1859 | Opened from Plymouth to Truro |

| 1863 | Opened Truro to Falmouth |

| 1867 | Branch opened to Keyham Dockyard |

| 1876 | Cornwall Loop line opened in Plymouth |

| 1889 | Line sold to the Great Western Railway |

| Engineering | |

| Engineer | Isambard Kingdom Brunel |

| Gauge | 7 ft 1⁄4 in (2,140 mm) Brunel gauge converted to 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge in 1892 |

| Successor organisation | |

| 1889 | Great Western Railway |

| 1948 | British Railways |

| Key locations | |

| Headquarters | Truro, Cornwall |

| Workshops | Lostwithiel |

| Major stations | St Austell Truro Falmouth |

| Key structures | Royal Albert Bridge and numerous timber trestle viaducts |

| Route mileage | |

| 1859 | 53.50 miles (86.10 km) |

| 1863 | 65.34 miles (105.15 km) |

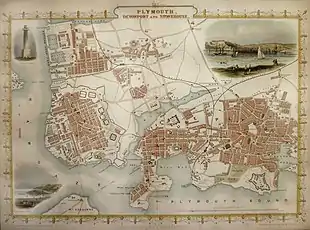

The Cornwall Railway was a 7 ft 1⁄4 in (2,140 mm) broad gauge railway from Plymouth in Devon to Falmouth in Cornwall, England, built in the second half of the nineteenth century. It was constantly beset with shortage of capital for the construction, and was eventually forced to sell its line to the dominant Great Western Railway.

The Cornwall Railway was famous for building the majestic Royal Albert Bridge over the River Tamar and, because of the difficult terrain it traversed, it had a large number of viaducts, built as timber trestles because of the shortage of money. They proved to be iconic structures, but were a source of heavy maintenance costs, eventually needing to be reconstructed in more durable materials.

Its main line was the key route to many of the holiday destinations of Cornwall, and in the first half of the 20th century it carried holidaymakers in summer, as well as vegetables, fish and cut flowers from Cornwall to markets in London and elsewhere in England. The section from Truro to Falmouth, originally part of its main line, never fulfilled its potential and soon became a branch line. Nonetheless the entire route (with some minor modifications) remains open, forming part of the Cornish Main Line from Plymouth to Penzance. The Truro to Falmouth branch continues: the passenger service on it is branded the Maritime Line.

General description

The Cornwall Railway was conceived because of fears that Falmouth would lose out, as a port, to Southampton. Falmouth had for many years had nearly all of the packet trade: dispatches from the Colonies and overseas territories arrived by ship and were conveyed to London by road coach. The primitive roads of those days made this a slow business and Southampton was developing in importance. The completion of the London and Southampton Railway in 1840 meant that dispatches could be taken on to London swiftly by train.[1][2]

Controversy over the route

At first the promoters wanted the most direct route to London, even if that meant building a line all the way there, bypassing important towns in Cornwall and Devon. Before the interested parties could raise the money and get parliamentary authority for their line, the Government actually removed the bulk of the packet trade to Southampton,[1] so that most of the income for any new line was removed. Some interests continued to press for the best line to London, hoping that the packet trade would return; if necessary they would link with another new railway, but the huge cost of this proved impossible to raise. A more practical scheme running to Plymouth gradually took priority, and at first the trains were to cross the Hamoaze, the body of water at the mouth of the River Tamar on a steam ferry. This was shown to be unrealistic, and Isambard Kingdom Brunel was called in to resolve the difficulty. He designed the bridge over the River Tamar at Saltash, the Royal Albert Bridge: when it was built it was the most prodigious engineering feat in the world.[3] He also improved the details of the route elsewhere. By reaching Plymouth, the company could connect with the South Devon Railway and on to London over the Bristol and Exeter railway and the Great Western Railway. The line was built on the broad gauge.[1]

Deprived of the lucrative packet trade, the promoters now discovered that it was impossible to raise the money needed to build the line, and there was considerable delay until the economy of the country improved. The object of linking Falmouth to London was quietly dropped, and the line was built from Truro to Plymouth. At Truro another railway, the West Cornwall Railway, fed in, linking Penzance to the network. Falmouth was much later connected too, but only by a branch line.

Brunel designs a practical route

The terrain crossed by the railway was exceptionally difficult because of the number of north-south valleys intersecting the route. Because of the extreme shortage of money when the railway was being built, Brunel designed timber trestle viaducts; these were much cheaper but they incurred heavy maintenance costs and were eventually reconstructed in masonry or brick, or in a few cases made into embankments. The spindly appearance of these high viaducts made passengers nervous, but they provided a marked impression associated with the line (although Brunel did use the form of construction elsewhere). The shortage of money at construction also forced the company to install single track only.[1][4]

Once in operation, the line was still short of money, but it made some progress in converting the viaducts to more durable materials, and in doubling some sections of the route, but the need to convert to standard gauge in addition was too much and the company was obliged to sell out to the Great Western Railway.

If the original plan had been to carry the packet trade, the railway as built developed a considerable agricultural business when it emerged that horticultural produce could be got to London markets quickly. In addition, holiday trade developed as Cornwall became a desirable holiday destination, and as numerous resorts served directly by the railway found favour. The area became branded as "the Cornish Riviera", rivalling the French Riviera for the well to do and the middle classes. Many branch lines were built to coastal resorts, nearly all by independent companies or later by the Great Western Railway.[4]

The twentieth century

In the twentieth century the Great Western Railway encouraged these two traffics by running fast goods trains from the area to London and other population centres, and by heavily marketing the holiday opportunities of Cornwall and providing imaginative train services for the purpose. Mineral traffic developed too.

Having been built cheaply, the route was difficult to operate as speeds and traffic density increased, as many sharp curves and very steep gradients militated against efficient operation. On summer Saturdays in later years serious delay due to congestion. Although the Great Western Railway made some improvements in capital schemes in Cornwall, the constructed topography of the main line made large scale improvement prohibitively expensive.

From the mid-1960s when holidaymakers began to look abroad for holidays in the sun, the Cornish Riviera inevitably declined, although a significant residual traffic remains. The mineral traffic also continues. Through passenger trains from London continue to operate and the original Cornwall railway route remains the backbone of rail business in the County.[5]

Origins

At the time of the accession of Victoria to the throne in 1837, Falmouth (with Penryn) was the largest population centre in Cornwall, at 12,000.[1] It had been an important victualling station for merchant shipping during the Napoleonic Wars, but Southampton was increasingly favoured for the continuing packet traffic,[note 1] due to its more convenient road and coastal shipping connection to London. Although official assurances had been given about the retention of certain traffics, the construction of the London and Southampton Railway, seriously proposed in 1830 and completed in 1840, alarmed interested businessmen in Falmouth, and it was generally agreed that a railway connection to London was urgently needed. (In fact the Government announced the transfer of all but the South American packet traffic to Southampton in 1842.)[1]

Early proposals, in 1835 and 1836, for the railway favoured a route broadly following the Old Road through Launceston and Okehampton, and on to Basingstoke or Reading. This huge undertaking failed for lack of funds, but it established the presumption that the part of this route west of Exeter, the Central Route, was the natural choice, and that the coastal route was not. The Central Route had the principal advantage of providing the shortest route to London, as the object was to secure the packet traffic. The intermediate terrain was largely unpopulated; the route traversed high altitudes, but the topography was easier than a route following the south coast because of the multiple valleys and river inlets near the coast.

Later proposals were put forward, now reduced to joining the London and South Western Railway (L&SWR) near Exeter; the L&SWR was very gradually extending westward, but these proposals all failed for lack of financial support. Nonetheless a Committee to form a Cornwall Railway had been formed and Captain William Moorsom had prepared detailed plans for a route.[1]

False starts in Parliament

On 29 May 1842 the Government announced that nearly all the packet traffic would be transferred to Southampton. The traffic forecast for the Cornwall Railway had assumed an income of £123,913 out of total income of £160,548. Thus the Central Route, by-passing the south Cornwall population centres, had lost 80% of its potential income at a stroke.[1] At the same time, the Bristol and Exeter Railway had reached Exeter, and the South Devon Railway to connect to Plymouth was definitely planned. A southerly route for the Cornwall Railway, to reach Plymouth, would secure considerable intermediate traffic, and shorten the route that the company would need to construct.

In August 1843 W. Tweedy, Chairman of the Cornwall Railway provisional committee, and William H. Bond, its secretary, approached the Great Western Railway (GWR) and found that the GWR was favourable to the idea of a connection between the Cornwall Railway and the South Devon line (with which the GWR was on friendly terms), but only if the Cornwall Railway adopted the southern route.

Crossing the Hamoaze

Moorsom's route to the "Steam Ferry" is shown as "New Passage Branch" (not actually built).

The South Devon Railway was originally going to build a branch to Devonport, and the Cornwall Railway was to start from there

Direct assistance was refused, but they were encouraged to promote an independent scheme, and in the autumn of 1844 the prospectus of the Cornwall Railway was produced. The Committee had firmly favoured the southern route, but many interested parties continued to support the northern alignment. Indeed this controversy dogged the company for years, even extending to supporters of the northern route opposing the Cornwall Railway bill in parliament. Moorsom designed a route with constant sharp curves and exceptionally steep gradients, which exposed him to criticism by respected railway engineers.[1]

The line was put forward for the 1845 session of Parliament. Captain Moorsom was again the Engineer. The line was to run from Eldad in Plymouth, the intended western terminus of the South Devon Railway, to Falmouth. From Eldad it was to descend at 1 in 30 (close to the present-day Ferry Road) to reach the steam chain ferry (described at the time as a "floating bridge" or "steam bridge") at Torpoint, or "New Passage", and run westwards, south of the River Lynher, climbing to cross Polbathick Creek by a wooden drawbridge, to St Germans. From a few miles west of that point, it would follow the course of the present-day route, but with more numerous and sharper curves and steeper gradients, via Liskeard, near Bodmin and Lostwithiel, then Par and St Austell to near Probus. From that point the line would have diverged (from the present-day route) to Tresillian, crossing the Truro River by a 600 feet viaduct south of the city, to Penryn, crossing the Penryn River from the north by embankment and drawbridge to enter Falmouth.

The Torpoint ferry had been in operation since at least 1834, having been developed by J M Rendel. Moorsom appears not to have given much thought to the practicalities of using the crossing, which would have involved through trains being divided and each portion then being propelled down a very steep gradient[note 2] onto the ferry boat; and each portion being hauled up a steep gradient and re-formed on the other side.

The supporters of the Central Route were able to point out the practical difficulties; Rendel himself gave evidence:

Mr Rendell [sic], engineer, deposed that he constructed the present steam ferry boats or bridges at the Hamoaze. These were worked by chains, which extended to either shore; and when wind and tide was strong, the chains formed a species of arc, and the platform [the deck of the boat] was not at right angles with the landing place. Considerable difficulty would therefore arise in bringing the rails of the bridge so immediately in contact with the rails of the landing place, [in order] that the trains might easily and safely run on and off the bridge; besides that, a difficulty arose from the great fall in the tide, which at spring was no less than 18 feet [5 m]. [He] was of opinion that by a train being stopped, divided, and placed upon the steam bridge, and landed on the opposite side of the Hamoaze, tackled together, and put in motion, a great delay would be occasioned, independent of the seven or eight minutes in crossing, of from eight to twelve minutes on each side.[7]

Penryn

The embankment across Penryn Creek was similarly ill thought through. There was to be an embankment (or viaduct) with a drawbridge to pass ships to Penryn Harbour; the waterway was tidal, of course, and the sailing ships needed sea room to beat up the channel, and needed to do so at the top of the tide. Steep railway gradients were necessary either side of the crossing. Evidence was given that the obstruction by Moorsom's embankment made it quite unacceptable, and several "memorials" had been submitted to that effect. In his evidence at the Lords Committee, Moorsom seemed to know little of the formal objections to the scheme.[8]

The atmospheric system

Moorsom planned to use the atmospheric system of traction. In this system a tube was laid between the rails, and a wagon with a piston running in the tube led the train. No steam locomotive was required; stationary steam engines at intervals evacuated air from the tube. The advantages seemed considerable: there was no need to convey the weight of the engine, and its fuel and water, on the train; more tractive power could be applied than the early locomotives could provide; and head-on collisions were considered to be impossible. The system had been operating, apparently successfully, on a 1+3⁄4-mile (2.8 km) section of the Dublin and Kingstown Railway (D&KR) and, less successfully, on the London and Croydon Railway. It appeared particularly appropriate for steeply graded lines like the Cornwall Railway, and it was planned for use on the South Devon Railway.

After an inspection of the Dalkey section of the D&KR, Moorsom reported to the Provisional Committee:

I am of opinion that the system is applicable with certainty and efficiency to the Cornwall Railway. That a sufficient power may be obtained so as to work the trains, which I think your traffic will require, at an average speed of 30 miles an hour for passenger trains, and from 15 to 20 miles an hour for goods, including stoppages in both cases, and that special trains may be despatched at greater speed if necessary.

The capital cost including the laying of the tube and building the engine houses would apparently be no more expensive than a locomotive line without them:

I am inclined to believe that ... we may find the original or prime cost not to exceed that which we have all along contemplated for establishing the locomotive line, £800,000. ... The annual cost will, probably, be reduced by 20 per cent below what we have heretofore contemplated, and the public will have the convenience of more frequent trains, which will again re-act in an increase of traffic.[9]

The newspaper report continues:

Captain Moorsom was then instructed to survey the line between Falmouth and Plymouth, the distance of which he found to be about 66 miles over the line selected. By using the atmospheric traction on this line, the trains may run from Falmouth to Plymouth in 2+1⁄2 hours, the Tamar being crossed without change of carriage by means of the steam-bridge.[10]

The 1845 Bill accordingly included the intention to use the atmospheric system. However, a Parliamentary report[11] on the application of the atmospheric system on railways in general was inconclusive, and only muddied the waters.[1]

The 1845 Bill rejected

The result of the 1845 Bill submission was that the preamble was proved but that the Committee stage in the House of Lords rejected the Bill: this meant that the desirability of the line was accepted, but that the detail of Moorsom's design was considered unsafe.[1]

A practical scheme at last

Despite the setback, the supporters of the line knew that they were close to getting approval. As a result Moorsom was dismissed and Isambard Kingdom Brunel was asked to design a new scheme for the 1846 session. Brunel brought in William Johnson, whom he fully trusted, to survey and redesign the line. This was a full fresh survey and not simply a tidying up of Moorsom's work. It was ready within three months and was lodged in Parliament with a new Bill on 30 November 1845.[1]

Starting from Eldad, the route would curve to the north and cross the River Tamar about two miles above Torpoint, by a fixed bridge, running close to the north bank of the Lynher to St Germans. West of that place, following the general course of Moorsom's design, he considerably improved the curves and gradients. From Probus the line would now run to the northern margin of Truro and then south to Falmouth. This avoided the crossing of the Truro River and the objectionable crossing at Penryn. By now the shortcomings in the atmospheric system were becoming apparent, and nothing more was heard of that system for the Cornwall Railway.

Although the magnitude of the Tamar crossing was daunting, Brunel was persuasive in giving evidence supporting it. In fact the Bill admitted the possibility of using the Hamoaze ferry but Parliament mandated the bridge[12] Detail of how the bridge at Saltash was to be made was vague at this stage, and it may be that Brunel's powers of persuasion deflected detailed examination of this.[13]

The line was to be 63 miles 45 chains (102.29 km). The authorised share capital was £1,600,000 with borrowing powers of £533,333, and the Associated Companies (the GWR, the B&ER and the SDR as a bloc) were authorised to subscribe. There were to be branches to Padstow, to the Liskeard and Caradon Railway, and to the quays at Truro and Penryn, and the Company was authorised to purchase the Bodmin and Wadebridge Railway, the Liskeard and Caradon Railway and the Liskeard and Looe Union Canal. (None of the branches and purchases were activated in the form envisaged in the Act.) The line was to be of the same track gauge as the GWR.

The scheme obtained royal assent on 3 August 1846.[1]

Work starts

At this time the general financial depression following the railway mania had set in, and apart from a small amount of work near St Austell, little progress in constructing the line was made, except for an investigation of the river bed for the Saltash crossing; this was completed by March 1848.

The railway mania was a phenomenon in which a huge number of railway schemes were put forward, when investors imagined that huge gains on investment were certain. Investors overcommitted themselves, and many lost substantial sums; money became scarce even for respectable schemes as subscribers simply had no money to pay calls on their shares. At the same time labour and material prices escalated substantially.

At a meeting in February 1851, Brunel informed the directors that if the scheme were reduced to a single line, the whole route could be constructed for £800,000, including the Tamar crossing and all stations. In April 1852 the directors proposed a capital reconstruction that reduced the commitment of subscribers. Many subscribers defaulted on their commitment nonetheless, but the financial reconstruction enabled the directors to proceed with construction between Truro (from the West Cornwall Railway near Penwithers Junction) and St Austell, and shortly after to Liskeard, about 37 miles (60 km) in total, as well as, in January 1853, the letting of a £162,000 contract for construction of the bridge over the Tamar.

However the severe shortage of money further inhibited progress, with shareholders failing to respond to calls (in which they should have paid for their shares in instalments) and by summer of 1854 more than half the company's shares had been forfeited from this cause. The directors now approached the Associated Companies (a consortium of the Great Western Railway, the Bristol & Exeter Railway and the South Devon Railway) for financial help, and in June 1855 a lease of the line was agreed, by which the Associated Companies guaranteed the Cornwall company's debentures (bank borrowings). This considerably eased the financial difficulties, enabling further contracts to be let.

Construction of the Saltash bridge started in May 1854 with the floating out of the "Great Cylinder"—the caisson to be used for founding the central pier in the tideway. In October 1855 the contractor, Charles John Mare, building the Tamar bridge failed, and after a delay, the company started undertaking the continuation of the work itself, under the supervision of Brunel's assistant, Robert Pearson Brereton. The huge undertaking proceeded slowly, but it was completed in 1859. The bridge is about 730 yards (670 m) long, with the two great main spans each of 455 feet (139 m) and numerous side spans. The total cost was £225,000 (equivalent to £23,977,266 in 2021).[14] A fuller description of the bridge and its construction is in the article Royal Albert Bridge.

East of the bridge, the South Devon Railway had planned a Devonport branch from its Plymouth station at Millbay, opened with their line in April 1849. The Cornwall company purchased the branch from them in 1854, and extended it by 1858 to join with the Tamar bridge. The South Devon company extended their station to handle the Cornwall's traffic, and agreed to use of the first half-mile of their railway from Millbay to the divergence of the Cornwall Railway. A Joint Committee with the South Devon company was established to oversee the operation of the Mill Bay[note 3] station.[15]

Construction of the section of route between Truro and Falmouth had been let to a contractor, Sam Garratt, but he had become bankrupt, and the Falmouth section was not pursued at this stage.[16]

Opening at last

All was practically ready now, and a train had run from Plymouth to Truro on 12 April 1859.[15] in a ceremony on 2 May 1859 the Prince Consort opened the new bridge, giving consent to naming it the Royal Albert Bridge. The line was opened throughout from Plymouth to Truro for passenger trains on 4 May 1859, and goods trains started on 3 October 1859. Passenger trains were limited to 30 mph (48 km/h) throughout and goods trains to 15 mph (24 km/h); due to the shortage of money, the rolling stock fleet was very small and the train service sparse, with correspondingly low income.

There was a difficulty about the construction of the Bodmin station (now Bodmin Parkway); it was planned to be at a place called Glynn, but the landowner "had originally pressed for the railway to be concealed in a tunnel, a luxury that the company would not be able to afford." There was accordingly a temporary station at Respryn, a little to the west; until the proper station could be completed, "the Bodmin traffic will be accommodated at a temporary wooden shed erected near [Respryn]".[17] The proper station was "completed shortly after the opening [of the railway"].[15]

After a slow start commercially, by August 1861 the directors of the company recorded their pleasure that large volumes of fish, potatoes and broccoli had been carried from West Cornwall. This had been transported to Truro by the West Cornwall Railway which had a line from Penzance to Truro; the West Cornwall company was a standard gauge line, and all goods had to be transshipped into different wagons at Truro due to the break of gauge there.

Extension to Falmouth but loss of control

The directors wished to extend their line to Falmouth, the original objective of the line, but money was still very difficult to obtain, and once again the company had to resort to asking the Associated Companies for finance. This was forthcoming in return for a 1000 year lease of the line to the Associated Companies, an arrangement that was authorised by Act of Parliament in 1861. A Joint Committee of Management was set up, consisting of four Cornwall Railway directors, three from the South Devon company, three from the Bristol & Exeter and two from the Great Western.

A new start was made on constructing the Falmouth extension, and this was opened on 24 August 1863 (and for goods trains on 5 October). A new dock had been opened at Falmouth since the original plans for the railway, and despite the decline in the significance of Falmouth docks to the railway company, an extension to that location was made, and a connection to the Dock Company's own rail network was made in January 1864.[4][15]

The West Cornwall Railway had been opened as a standard gauge line but there was a legal provision that enabled the Cornwall Railway to demand that they install broad gauge rails. Since this was obviously conducive to more efficient operation, the Cornwall company activated the requirement in 1864.[15] The West Cornwall company was in the same severe financial difficulty as the Cornwall Railway, and had to surrender its line to the Associated Companies, who themselves installed the broad gauge rails. The takeover took effect from 1 July 1865, and broad gauge goods trains started running on 6 November 1866, with passenger trains from 1 March 1867. This significantly improved operations, and with through passenger trains running from Penzance to London, the subordinate status of the Falmouth line was emphasised: it was now simply a branch line, thought of recapturing the packet traffic having long since been forgotten.

The Associated Companies amalgamated as the Great Western Railway early in 1876, and that company was now the only lessee of the Cornwall line, and the Joint Committee of Management now consisted of eight Great Western directors and four Cornwall directors.

Income creeps up but expenditure accelerates

Some small improvement in the financial situation of the company took place over the ensuing years, but the timber viaducts had always been a liability due to their very high maintenance cost, at about £10,000 annually. Replacement of some of them on the grounds of urgent technical need had started in 1871 and was continuing progressively; they were being built of a width suitable for a double standard gauge line, although for the time being the line was a single broad gauge line. The work was being ordered by the Joint Committee of Management, but in November 1883, the minority Cornwall Railway directors asserted themselves and pointed out that authorising such major works was a matter for the board of directors instead; and the original Cornwall Railway directors were a majority there. The impasse went to arbitration and the arbitrator ruled that under the terms of the lease, the railway was to be maintained as a broad gauge line. As the ultimate cessation of broad gauge operation was by now plain, this frustrated any practical progress on the reconstructions, and in fact no new viaduct reconstructions were started as long as the Cornwall company remained in existence.[18]

In the year ending June 1879, the gross receipts were £125,034 (equivalent to £13,525,089 in 2021),[14] compared with an average of £130,000 per annum in previous years. Accumulated losses since June, 1866 amounted to £149,384 (equivalent to £16,159,060 in 2021);[14] an average of £11,000 per year. A meeting in September 1879 optimistically concluded that it may be some years before there is a surplus for the paying out of dividends, but there was still an ultimate value in Cornwall shares.[19] In fact the separate existence of the company was nearing its end, and in 1888 ordinary shareholders accepted a cash purchase of their shares, and the Cornwall Railway Company was dissolved on 1 July 1889, the line passing fully into Great Western Railway ownership.

Now part of the Great Western Railway

The train service during the Cornwall Railway years had been of five passenger trains each way daily, calling at all stations; there was an additional train each way in the summer months. As well as the stations themselves there were stops at ticket platforms at Truro and Falmouth, and the journey time was two hours 30 minutes Plymouth to Truro (53 miles, 85 km) and a further half-hour to Falmouth (13 miles, 21 km). (The service from Penzance to London was by through carriage, shunted from one train on to another.) For the time being, the Great Western Railway made no effort to improve the train service, and other issues dominated.

The decision had been taken to convert the gauge to standard, and preparations for this culminated in the prodigious task of the actual conversion of the Cornwall Railway route in common with the rest of the broad gauge parts of the route over a single weekend, opening as a standard gauge line with a full train service on the morning of Monday 23 May 1892.

The line was single track throughout except for a little over a mile from near Millbay to Devonport, but in 1893 further sections of the line were progressively opened in double track, and by early 1904 only the Royal Albert Bridge and a section of about five miles from there to St Germans remained single. Similar work was being undertaken on the line of the former West Cornwall Railway, the route from Plymouth to Penzance now being treated as a unit.

The Saltash to St Germans section was by-passed by an inland deviation which was opened for goods trains on 23 March 1908 and for passenger trains on 19 May; the former route section was then closed and abandoned. This left only the Royal Albert Bridge as the only single line section on the main line to Truro (Penwithers Junction). The Falmouth branch was never doubled.

Following the amalgamation, plans were put in place for the gauge conversion, which took place over the weekend of 21 May 1892.

The replacement of the timber viaducts, started by the Cornwall Railway itself and then suspended, was resumed and between 1896 and 1904 all the remaining timber viaducts on the Plymouth to Truro line were replaced by masonry, or masonry and iron, structures. However, the structures on the lightly trafficked Falmouth branch continued for some years, finally being replaced by 1927.[4][15][20]

Remaining Cornwall Railway structures

Of the structures built by the Cornwall Railway, the most impressive is the Royal Albert Bridge, still fully operational.

Many of the piers of Brunel's original timber viaducts remain today, having been left in place when the replacement viaduct was built alongside. The original viaducts are fully discussed in the article Cornwall Railway viaducts.

Many smaller masonry bridges, and the stations at Liskeard and St Germans remain in use. The stations standing at Par and Saltash were also built by the Cornwall Railway, although these were later constructions. The footbridge at St Austell is a rare example of a Great Western Railway footbridge that still retains a roof. On the Falmouth extension there is an original goods shed at Perranwell and a group of 20 workers' cottages at Falmouth.

Branches

Apart from a short branch at Keyham opened on 20 June 1867 to serve the naval dockyards, no branches were ever built by the Cornwall Railway. Independent railways did however form junctions: the West Cornwall Railway to Penzance (1859), Lostwithiel and Fowey Railway (1869), and the Newquay and Cornwall Junction Railway (1869).

Other independent lines were proposed but failed during the economic depression following the collapse of the Overend, Gurney and Company bank, notably the Saltash and Callington Railway, and the Bodmin and Cornwall Junction Railway.

The Cornwall Loop was opened at Plymouth on 17 May 1876, forming the north chord of a triangle there, to avoid reversing trains in the terminus at Millbay. It was mainly used by London and South Western Railway trains at first but later found use for fast passenger and perishable goods trains, and is now the main line.

Stations

See Cornish Main Line and Maritime Line for stations opened after 1889 by the Great Western Railway or its successors.

- At Plymouth, Cornwall Railway trains used the South Devon Railway station at Millbay (closed 1941)

- Devonport

- Saltash

- St Germans

- Menheniot

- Liskeard

- Doublebois (1860–1964)

- Bodmin Road (Temporarily located at Respryn, a little to the west of the present station, for seven weeks in 1859 until the permanent station was completed; renamed Bodmin Parkway in 1983)

- Lostwithiel

- Par

- St Austell

- Burngullow (opened 1863; relocated somewhat to the west in 1901; closed 1931)

- Grampound Road (closed in 1964)

- Truro

- Perranwell (1863, originally Perran until 1864)

- Penryn (1863)

- Falmouth (1863-1970; reopened 1975 and renamed Falmouth Docks in 1989)

Rolling stock

Locomotives

The locomotives were provided under a contract with Messrs Evans, Walker and Gooch. This enabled the expensive equipment to be provided without a huge capital outlay.[21]

The South Devon Railway took over the contract in 1867 and worked both of the companies' lines and also that of the West Cornwall Railway with one common pool of engines, although throughout both contracts the Cornwall Railway was responsible for ordering its own engines and was charged for their costs. The locomotives bought for the Cornwall Railway were:

- Eagle class 4-4-0ST passenger locomotives

- Castor (1865–1882) GWR no. 2121, originally intended to be named Fal

- Cato (1863–1877) GWR no. 2118

- Eagle (1859–1876) GWR no. 2106

- Elk (1859–1877) GWR no. 2107

- Gazelle (1859–1865) GWR no. 2110

- Lynx (1859–1876) GWR no. 2109

- Mazeppa (1859–1885) GWR no. 2111

- Pollux (1865–1892) GWR no. 2120, originally intended to be named Tamar

- Wolf (1859–1878) GWR no. 2115

- ex-Carmarthen and Cardigan Railway 4-4-0ST passenger locomotive

- Magpie (1872–1889) GWR no. 2135

- Dido class 0-6-0ST goods locomotives

- Argo (1863–1892) GWR no. 2151

- Atlas (1863–1885) GWR no. 2152

- Dido (1860–1877) GWR no. 2143

- Hero (1860–1887) GWR no. 2144

- ex-Great Western Railway Sir Watkin class 0-6-0ST goods locomotives

- Bulkeley (1872–1890) GWR no. 2157

- Fowler (1872–1887) GWR no. 2158

- Buffalo class 0-6-0ST goods locomotives

- Dragon (1873–1892) GWR no. 2164

- Emperor (1873–1892) GWR no. 2167

- Hercules (1872–1889) GWR no. 2163

Carriages and wagons

Carriages and wagons were bought by the Cornwall Railway and maintained at workshops established at Lostwithiel. These workshops also had equipment for preparing timber for the viaducts and permanent way.[22]

At the opening of the line there was provided 8 first class, 18 second, 16 third, and 4 composite carriages; in 1861 a post office sorting carriage was provided. These were all six-wheel vehicles. By 1889 there was 1 less second class but 3 more third class carriages plus 6 luggage vans. Initially 30 mineral and 20 cattle trucks were provided, along with 8 brake vans, 10 carriage trucks, 8 ballast trucks, and 2 timber trucks. By 1889 this fleet had grown to 421 vehicles. There were also 15 vans for carrying meat, and 9 horse boxes.[15]

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Howes 2012.

- ↑ Williams, Ronald Alfred (1968). The London & South Western Railway. Vol. 1. Newton Abbot: David & Charles.

- ↑ Binding, John (1997). Brunel's Royal Albert Bridge. Truro: Twelveheads Press. ISBN 0-906294-39-8.

- 1 2 3 4 MacDermot, E.T. (1931). History of the Great Western Railway, vol II. London: Great Western Railway Company.

- ↑ Semmens, P.W.B. (1990). The Heyday of GWR Train Services. Newton Abbot: David & Charles Publisher plc. ISBN 0-7153-9109-7.

- ↑ Howes 2012, p. 127.

- ↑ Evidence of Rendel in Lords Committee hearing, reported in Woolmer's Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 10 July 1845

- ↑ Moorsom's evidence before the Lords Committee, 29 May 1845, quoted in Howes pp 94–95

- ↑ Captain Moorsom to the Provisional Committee of the Cornwall Railway at a meeting "recently" held at Truro, reported in the Taunton Courier, 11 September 1844; original orthography retained.

- ↑ Editorial in the Taunton Courier 11 September 1844

- ↑ Report from the Select Committee on Atmospheric Railways, House of Commons, 24 April 1845, quoted in Howes

- ↑ Howes 2012, p. 133.

- ↑ Howes 2012, pp. 134–135.

- 1 2 3 UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Woodfin, R.J. (1972). The Cornwall Railway to its centenary in 1959. Truro: Bradford Barton. ISBN 0-85153-085-0.

- ↑ Howes 2012, p. 159.

- ↑ West Briton newspaper, quoted in Howes. Howes cites the date of the newspaper as 5 September 1845, but this seems to be far too early.

- ↑ Binding, John (1993). Brunel's Cornish Viaducts. Penryn: Atlantic Transport Publishers. ISBN 0-906899-56-7.

- ↑ "The Cornwall Railway". The Cornishman. No. 61. 11 September 1879. p. 6.

- ↑ Osler, Edward (1982). History of the Cornwall Railway 1835–1846. Weston-super-Mare: Avon-Anglia Publications. ISBN 0-905466-48-9.

- ↑ Reed, P.J.T. (February 1953). White, D.E. (ed.). The Locomotives of the Great Western Railway, Part 2: Broad Gauge. Kenilworth: The Railway Correspondence and Travel Society. ISBN 0-901115-32-0. OCLC 650490992.

- ↑ Bennett, Alan (1988). The Great Western Railway in Mid Cornwall. Southampton: Kingfisher Railway Publications. ISBN 0-946184-53-4.

- Howes, Hugh (2012). The Struggle for the Cornwall Railway—Fated Decisions. Truro: Twelveheads Press. ISBN 978-0-906294-74-1.

Further reading

- Mosley, Brian (February 2013). "Cornwall Railway". Encyclopaedia of Plymouth History. Plymouth Data. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Cornwall Railway Company and other records at The National Archives

- Measom, George (1860), Official Illustrated Guide to the Bristol and Exeter, North and South Devon, Cornwall, and South Wales Railways, London: Richard Griffin and Co.

- Kittridge, Alan (4 January 2024). Rendel's Floating Bridges. Truro: Twelveheads Press. ISBN 978-0-906294-67-3.