Cortain (also spelled Courtain, Cortana, Curtana, Cortaine or Corte) is a legendary short sword in the legend of Ogier the Dane. This name is the accusative case declension of Old French corte, meaning "short".[1]

Attestations

The tradition that Ogier had a short sword is quite old. There is an entry for "Oggero spata curta" ("Ogier of the short sword") in the Nota Emilianense (c. 1065–1075),[2] and this is taken as a nickname derived from his sword-name Cortain.[3] The sword name does not appear in the oldest extant copy of The Song of Roland (Oxford manuscript), only in versions postdating the Nota.[4][lower-alpha 1]

The sword and its early provenance is described in the chanson de geste Le Chevalerie Ogier.[6][7] The sword has appeared in other chansons de geste somewhat predating Chevalerie Ogier, or composed around the same time as it, such as Aspremont (before 1190) and Renaut de Montauban (aka Quatre fils Aymon, c. 1200).[8]

Provenance

Generally according to traditional French sources, Cortain was previously owned by the courteous Saracen knight Karaheut, and given to Ogier.[9][11]

According to the first branch (enfances) of Le Chevalerie Ogier, Ogier was still unknighted and sent as hostage to King Charlemagne. Thus when the French began to fight Saracens invading Rome, the unarmed Ogier only spectated. Eventually however he entered the fray, wresting the arms of the standard-bearer Alori who fled in retreat.[12][13] His deeds were rewarded by knighthood, and Charlemagne girt him with his own sword.[14][15]

In the continued conflict, the Saracen Karaheut of India[lower-alpha 2][lower-alpha 3] who owned Cortain challenged Ogier to duel. Karaheut's weapon, "the sword Brumadant the Savage"[22][lower-alpha 4] was remade more than twenty times by the swordsmith Escurable; when it was tested on a block of marble it broke about a palm's length, and had to be reforged shorter-bladed; hence it was [re]named Corte or Cortain,[29] meaning "Short".[6][7] This became the weapon of a chivalric-minded Karaheut,[30] who gave his destrier and arms (including Cortain) to Ogier so he could now fight the new opponent, Brunamont, in single combat.[lower-alpha 5][lower-alpha 6][35][36][37]

Renaud de Montauban

Ogier tested the sword on a perron (stone block[lower-alpha 7]) and the sword got chipped (a "half a foot"; Old French: demi pié"[40][42]), giving rise to the name "Cortain (Short)", or so it has been told in the poem Renaud de Montauban (aka Quatre Fils Aymon).[43][44][lower-alpha 8]

Saga I version

According to the Old Norse version Karlamagnús saga Part I (c. 1240[45]), Karlamagnús (Charlemagne) tested three swords at Aix-la-Chapelle, and the first that only made a notch in the steel mound or block[lower-alpha 9] received the name "Kurt" (Cortain), the second that cut a hand-width "Almacia", and the third chopped off a chunk more than a half a foot" (possibly 1/2 foot measure (6 in (150 mm)), or "half leng-lenth"), earning the name Dyrumdali".[51][lower-alpha 10][53] Thus this Scandinavian account fails to explain how the sword got its name, unlike the French text which reveals that the sword was curtailed when tested.[54] The meaning of "Kurt" in Old Norse would be "courtesy" or "chivalry".[55]

All three swords were received as ransom from a Jew[58] named "Malakin of Ivin", and all made by Galant of England,[59] namely Wayland the Smith,[60] not the sword-maker named in Chevalerie.[39]

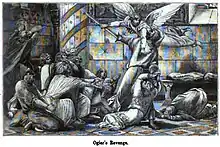

Blocked by angel

Ogier turned rebel (after Prince Charlot murders his son Bauduin/Baldwinet over chess[63][64]), and eventually was made prisoner in later branches of Le Chevalerie Ogier. In the ninth branch, he was offered reprieve in exchange for cooperating with fighting a new wave of Saracens, but refused unless he could exact vengeance against Charlot.[65][66] Ogier was about to strike Courtain upon Charlot, when the archangel Michael interceded, holding the sword by its blade or edge,[67] and staying the execution.[68][69]

Post-13th century

The sword recurs in the later poems in the decasyllabic (c. 1310[70]) and Alexandrine (c. 1335[71]) versions, and the 15th century[72] prose romance of Ogier, e.g., the scenes of Karaheu (Caraheu) using it in single combat with Ogier.[73] The prose redactor retained the episode of an angel (though he was an anonymous "ung ange de paradis", not specifically St. Michael) who "holds back the stroke of Ogier's sword and took the sword by the point (retint le coup de l'espee d'Ogier et print l'espee par la pointe)" to stop Ogier from killing Charlot with the sword Courtain.[74] Later printed editions have further altered this to stating (in chapter summary) that the angel held back Ogier's arm.[75]

Various accounts of the sword, Kortone, are also given in the Danish Olger Danskes krønike (1534), adapted from the French prose. The work notes that the sword could still be viewed at the "cloister of St. Bent (=Benedict[76])'s order" at Meaux (near Paris) in France.[77][78] It also records the episode of Olger's sword Kortone being stopped by the angel (see fig. right).[79]

Arthurian cycle

The Prose Tristan (1230–1235, expanded in 1240[80]) also names Ogier as eventual owner of the sword, though claiming it to have been a relic of the Arthurian knight Tristan (Tristram). Since the sword was originally too long and too heavy, Ogier shortened it and named it Cortaine.[lower-alpha 11][81][82][83] According to this French narrative, Charlemagne brought discovered the swords of Tristan and Palamedes in an abbey in England, giving the Tristan sword to Ogier, and girt Palamedes' sword on himself, which was judged to be a superior sword.[81]

In the La Tavola Ritonda (mid-14th to 15th century) based largely on the Italian translation of the Prose Tristan, Tristan's sword is named Vistamara, considered the best and sharpest in the world.[84][85] In this version Charlemagne (Carlo Magno) comes to Verzeppe Castle (presumably Leverzep/Louvezerp) in Logres[87] and finds the statues of five eminent Arthurian knights, each wearing their original sword.[88] Tristan's sword was given to Ogier (Ugieri) who was the only one capable of wielding the heavy sword, but the sword was clipped short upon its first use, and so was named Cortana.[89][82]

The English monarchy also laid claim to owning "Tristram's sword",[lower-alpha 12] and this according to Roger Sherman Loomis was the "Curtana" ("short") used in the coronation of the British monarch. Loomis also argues that Curtana's origins as Tristram's sword was known to the author of this passage in Prose Tristan, but the tradition was forgotten in England.[83] The English royal Curtana had been once been jagged at its broken tip, and in the Tristan/Tristram romances, the hero's sword broke off, with its tip lodged in Morholt's head.[90]

Notes

- ↑ Cortein (Roland, Chateauroux ms., laisses CCCCXXI, CCCCXXXV),[5] Corten (Roland, Venice ms. VII, laisses CCCCXVIII, CCCCXXXII).[5]

- ↑ "Karaheut" in Ludlow (1865) and Voretzsch (1931), p. 209. Langlois, lists "Caraheu, Craheut, Karaheu, Karaheut, Karaheult, Kareeu".[16] "Karahues" and "Karahuel" are also used.

- ↑ Karaheut of India was son of King Gloriant (var. Quinquenant), brother of Marsile and cousin(relative) of Baligant and ([lacuna] fiancée of) Gloriande, daughter of the amiral.[17][15][18] Karaheut is described as "lover of Glorianda",[15] but she is more appropriately characterized as the fiancée.[19][20]

- ↑ Alternately it may have been "the sword [of] Brumadant the Savage". This Brumadant the sword-owner supposedly differs from the "maker of which" sword, according to one view,[23] but others thought this Brumadant was in fact the giant-smith who forged it.[24][25] The latter case conflicts with Langlois's reading which names Escurable as the sword-maker.[21]

- ↑ Brunamont de Maiolgre. Brunamont's homeland Maiolgre is not specified by Langlois,[31] and thogh Ludlow guesses it to be Majorca [32] in Spain, the variant reading "Calabre" (Calabria, Italy)[31] may suggest somewhere in Italy.

- ↑ The circumstances were that Karaheu persuaded Ogier to fight in single combat, but his comrades in large numbers interrupted and took Ogier hostage. Karaheu, failing to secure Ogier's release, surrendered himself to the French. Meanwhile the Amiral broke the engagement of his daughter Gloriande to Karaheu, awarding her to Brunamont. Gloriande then named Ogier her champion to fight Brunamont.[33][34]

- ↑ Cf. next note for commentary on possible meaning of perron besides "boulder block". Hieatt calls it "testing mound",[38] similar to "steel mound" used for sword-testing in the saga version.

- ↑ Leon Gautier concedes that in the context of the Chanson de Roland and Renaud here, the perron ought taken to mean a "massive rock construction" (as per Paul Meyer), though probably earlier the word referred to a natural rock formation. He claims moreover that perron was also interchangeably called plancher at an earlier time and was "nothing more than a wooden staircase", though he will refrain from discussing the lore of the steel staircase at the Aix Palace, where the knights tried out their swords (Cf. "steel staircase" used by Ogier to test his sword, mentioned in L. Gautier's reconstructed life of a French noble,Gautier (1884), p. 271, cited below).

- ↑ The original Old Norse phrase is stálhaugr, which Fritzner's dictionary merely defines verbatim as "steel mound" in Norwegian.[46] Hieatt's English translation thus give "steel mound", but the French side-by-side translation gives "mass of steel (masse d'acier)",[47] while Aebisher gave "steel block (bloc d'acier)"[48] In the French source Ogier's sword was tested on a perron (usually considered a stone block)[49][41] But in Leon Gautier's narrative, Ogier's sword was tested on the "steel staircase" at Aix.[50]

- ↑ Or "half a leg-length", since ON fótr} could mean "foot" or "leg".[52] Note that although Hieatt's English tr. gives "rent more than half the length of a man's foot" the French side-by-side tr. gives "moitié de la jambe d'un homme (half of human leg)" and Aebischer (1972), p. 131: "la troisième , et il tomba [de la masse] plus de la moitié d'une jambe d'homme" similarly states that a chunk that size "fell".

- ↑ This passage is not included in Curtis tr. (1994)'s English translation.

- ↑ King Johan received "duos enses scilicet ensem Tristrami.. (two swords, namely Tristram's sword.. )", Patent Rolls for 1207.

References

- Citations

- ↑ Togeby (1969), p. 17.

- ↑ Sholod, Barton (1966). Charlemagne in Spain: The Cultural Legacy of Roncesvalles. Librairie Droz. p. 189. ISBN 9782600034784.

- ↑ Togeby (1969), p. 112.

- ↑ Togeby (1969), p. 112 and Togeby (1969), p. 17

- 1 2 Foerster ed. (1883), pp. 383, 393.

- 1 2 Barrois ed. (1842) vv. 1647–1664. 1: 69.

- 1 2 Ludlow (1865), p. 256.

- ↑ Togeby (1969), p. 52.

- ↑ Barrois ed. (1842) Chevalerie Ogier, vv. 2700ff. Cf. Analyze, p. lxxij "Caraheu donne son épée a Ogier".

- ↑ Benoist Rigaud ed. (1579), p. 94: "Le Roy Caraheu parla à Ogier le Dannois &.. kuy donna courtain sa bon espee".

- ↑ Cf. also the printed French prose romance of 1579.[10]

- ↑ Barrois ed. (1842), pp. lxxi, 1–23, vv. 1ff; vv. 500–590ff

- ↑ Ludlow (1865), pp. 249–251.

- ↑ Barrois ed. (1842), pp. lxxij, 29–31, vv. 690ff, 747ff

- 1 2 3 Ludlow (1865), p. 252.

- ↑ Langlois (1904), Table des noms s.v. "Caraheu, etc., etc..

- ↑ Barrois ed. (1842) vv. 787–792 "C'est Kareeus fix le roi Gloriant (Quinquenant),/Frère Marsille et cosin Baligant, Drus Gloriande, la fille l'amirant.. gent/D'Ynde la fière dessi en Orient"

- ↑ Togeby (1969), p. 51.

- ↑ Barrois ed. (1842), p. lxxij: "Gloriande 1021; promise à Caraheu 1063"

- ↑ Cf.Farrier (2019), p. 64, Adenet le Roi, Enfances Ogier, summary

- 1 2 Langlois (1904), Table des noms s.v. "Brumadant: "Épée de Caraheux, forgée par Escurable".

- ↑ Old French: l'espée Brumadant le sauvage, v. 1647. Langlois describes Brumandant as the name of the sword forged by Escurable.[21]

- ↑ Dickens, Charles (17 February 1877). "Swords". All the Year Round. New Series. 17 (429): 535.

- ↑ Baron de Cosson (1891). "The Conyers Falchion". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle Upon Tyne. 5 (6): 43.

- ↑ Baldwin, James (1884). "Adventure VIII. How Ogier won Sword and Horse". La chevalerie. Paris: V. Palmé. pp. 81–96.

- ↑ Barrois ed. (1842), p. lxxiij, 69.

- ↑ Langlois (1904) Table des noms, s.v. "Corte, Cortain, Cortein, Courte, Courtain"

- ↑ Barrois ed. (1842), p. lxxiij, 77.

- ↑ This sword name first occurs as Corte at v. 1663,[26][27] but is spelt Courtain at v.1860[28] and most other occurrences in the poem.

- ↑ The courtois "Karaheu" in Togeby (1969), p. 51

- 1 2 Langlois (1904) Table des noms, s.v. "Maiogre, Maiogres (1)"

- ↑ Ludlow (1865), p. 259.

- ↑ Ludlow (1865), pp. 257–260.

- ↑ Barrois ed. (1842), p. 99 and n4, vv. 2395–2397

- ↑ Barrois ed. (1842) vv. 2633–2644. 1: 109.

- ↑ Ludlow (1865), p. 260.

- ↑ van Dijk, Hans (2000). "Ogier the Dane". In Gerritsen, Willem Pieter; Van Melle, Anthony G. (eds.). A Dictionary of Medieval Heroes: Characters in Medieval Narrative Traditions and Their Afterlife in Literature, Theatre and the Visual Arts. A Dictionary of Medieval Heroes. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 186–188. ISBN 978-0-85115-780-1.

- ↑ Hieatt tr. (1975a), note to Ch. 44, citing Renaud de Montauban, Michelant ed. (1862), p. 210.

- 1 2 3 Gehrt, Paul (1899). "Zwei altfranzösische Bruchstücke des Floovant". Romanische Forschungen. 10: 265.

- ↑ ""[39]

- 1 2 3 Paris, Gaston (1865). La chevalerie. Paris: A. Franck. p. 370.

- ↑ Gautier (1872), p. 169: "Courtain, l'épée d'Ogier.. fut écourtée d'un demi-pied, (V. Renaus de Montauban, éd. Michelant, p. 210, et la Karlamagnus Saga, i, 20, cité par G. Paris [Hist. Poet. Ch.], 370[41])

- ↑ Michelant ed. (1862), p. 210.

- ↑ Gautier (1884), p. 522, note

- ↑ Togeby (1969), p. 82.

- ↑ Fritzner (1867) Ordbog s.v. "stálhaugr"

- ↑ Togeby et al. (1980).

- ↑ Aebischer (1972), p. 25.

- ↑ Gautier (1872), p. 169 and Gautier (1884), p. 522, note

- ↑ Gautier (1891), p. 271.

- ↑ As for 1/2 foot unit measurement, Gehrt (1899) says Durendal "hewed off 1/2 ft." in the saga, and it can be corroborated he meant 1/2 ft., since he uses the same expression for Courtain "striking off 1/2 ft." in the chanson of Renaud, where the original reads "demi pié(pied)" ("drei von Galant.. den dritten, besten, der einen halben Fuss Stahl herunterhaut" (Karlamagnussaga) vs. "drei Helden, zuerst Roland, dann Olivier, dann Ogier. Der letztere.. einen halben Fuss herunterschlug").[39]

- ↑ Lindow, John (2002). Norse Mythology: A Guide to Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford University Press. p. 242. ISBN 9780198034995.

- ↑ Karlamagnús saga I. Kap. 44, Unger (1860), p. 40; Hieatt tr. (1975a), Part I, Ch. 44, p. 133; Togeby et al. (1980) (ON and Fr. side-by-side) Chapitre 41, p. 89

- ↑ Togeby (1969), p. 91.

- ↑ Hieatt tr. (1975a), Ch. 44 note 1

- ↑ Gautier (1872), p. 169.

- ↑ Aebischer (1972), p. 48: "Si Abraham est un inconnu , sans doute un Juif , Malakin , nom porté presque uniquement par des Sarrasins.."

- ↑ Not explicit in original text. Hieatt glosses Malakin as "usurer" in index; but the character is assumed to be a Jew (juif) by French scholars.[41][56][57]

- ↑ Karlamagnús saga I. Kap. 43, Unger (1860), p. 40; Hieatt tr. (1975a), Part I, Ch. 43, p. 132; Togeby et al. (1980) (ON and Fr. side-by-side) Chapitre 40, pp. 88–89

- ↑ Hieatt tr. (1975a), Ch. 43 note 2: "Weland, ..smith of Germanic legend"

- ↑ Gautier, Léon (1884). La chevalerie. Paris: Victor Palmé. pp. 608–609.

- ↑ Gautier, Léon (1891). Chivalry. G. Routledge and sons. pp. 429, 432, 21.

- ↑ Barrois ed. (1842) Branch II.

- ↑ Ludlow (1865), p. 262.

- ↑ Barrois ed. (1842) vv.10010ff. 2: 409.

- ↑ Ludlow (1865), pp. 292–296.

- ↑ Godefroy, Dictionnaire de l'ancienne langue. Tome 1. s.v. "Amore, -ure, -eure". '. s.f., lame d'épée, fil de l'épée'. Barrois ed., v. 10966 is given as an example.

- ↑ Barrois ed. (1842) vv.10979–11009. 2: 457–458. "Ch'iert sains Mikex, ce trovons-nos lisant: L'ameure tint del espée trenchant". "

- ↑ Ludlow (1865), p. 296.

- ↑ Togeby (1969), p. 134.

- ↑ Togeby (1969), pp. 148.

- ↑ Togeby (1969), p. 221: "XVIII. Le Roman d'Ogier en Prose (1496)"

- ↑ Poulain-Gautret (2005), pp. 91–92.

- ↑ Poulain-Gautret (2005), p. 228.

- ↑ Benoist Rigaud ed. (1579), p. 233 "Comment Charlemagne partit de Laon, etc., .. & comment l'Ange ainsi qu'il vouloit coupper lateste de Charlot luy retint le bras & des parolles qu'il luy dist". p. 245: "Dieu.. envoya un Ange de Paradis, qui retint le coup del'espee d'Ogier & luy dist.."

- ↑ Togeby (1969), p. 233.

- ↑ Hanssen (1842), p. 51.

- ↑ This is probably the reference to the effigies on the sarcophagi of "Ogier" and "St. Benedict" at Meaux.

- ↑ Hanssen (1842), pp. 138–139: "Men som han nu havd Svaerdet oppe i Veiret, da kom en Guds Engel af Himmelen ganske skinnende og hodt om Odden af Sværet, at Alle saae det stinbarlingen. Engelen sagte til Olger.

- ↑ The Romance of Tristan, translated by Curtis, Renée L., Oxford University Press, 1994, p. xvi ISBN 0-19-282792-8.

- 1 2 Löseth, Eilert [in Norwegian] (1890), Analyse critique du Roman de Tristan en prose française, Paris: Bouillon, p. 302 (in French)

- 1 2 3 Bruce, Christopher W. (1999). "Cortaine ("Shortened")". The Arthurian Name Dictionary. Garland. p. 131. ISBN 9780815328650.

- 1 2 Loomis, Roger Sherman (January 1922a), "Tristram and the House of Anjou", The Modern Language Review, 17 (1): 29, doi:10.2307/3714327, JSTOR 3714327

- ↑ Polidori, Filippo Luigi [in Italian], ed. (1864), La Tavola ritonda o l'istoria di Tristano: testo di lingua, Bologna: presso Gaetano Romagnoli, p. 192

- ↑ Tristan and the Round Table: A Translation of La Tavola Ritonda. Translated by Shaver, Anne. State University of New York at Binghamton. 1983. p. 125. ISBN 9780866980531.

- ↑ Bruce (1999) Arthurian name Dictionary, s.v. "Leverzep (Leverzerp, Lonazep, Lonezep, Louvezeph, Lovezerp, Verzeppe)"

- ↑ Bruce[82][86] Cf. Curtis tr. (1994), p. 313: "Castle Louvezerp" where a tournament takes place.

- ↑ Bruce (1999) Arthurian name Dictionary, s.v. "Charlemagne"

- ↑ Polidori ed. (1864), pp. 391–392

- ↑ Loomis, Roger Sherman (July–September 1922b), "Vestiges of Tristram in London", The Burlington Magazine, 41: 56–59

- Bibliograp

- (primary sources)

- Barrois, Joseph, ed. (1842). La chevalerie Ogier de Danemarche. Paris: Techener. Tome 1, Tome 2.

- Rigaud, Benoist [in French], ed. (1579). L'Histoire d'Ogier le Dannoys Duc de Dannemarche, Qui fut l'un des douze Pers de France. Lyon: Benoist Rigaud.

- Foerster, Wendelin, ed. (1883). Das altfranzösische Rolandslied. Text von Châteauroux und Venedig VII. Altfranzösisehe Bibliothek, VI. Helbronn: Verlag von Gebr[üder] Henniger.

- Michelant, Henri, ed. (1862). Renaus de Montauban oder die Haimonskinder, altfranzösisches Gedicht, nach den Handschriften zum Erstenmal herausgegeben. Bibliothek des Litterarischen Vereins in Stuttgart, 67. Stuttgart: Litterarischer Verein in Stuttgart.

- (primary sources—Scandinavian)

- Aebischer, Paul [in French] (1972). Textes norrois et littérature française du Moyen Age: La première branche de la Karlamagnus saga. Traduction complète du texte en narrois, pécédée d'une intruduction et suivie d'un index des noms propres. Textes norrois et littérature française du Moyen Age. Vol 2. (in Old Norse and French). Genève: Droz. ISBN 9782600028196.

- Hanssen, Nis, ed. (1842), Olger Danskes Krønike (in Danish), Fortale af C. Molbech, Kjöbenhavn: Louis Klein

- Karlamagnús saga: The Saga of Charlemagne and his heroes. Vol. 1. Translated by Hieatt, Constance B. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. 1975a. ISBN 0-88844-262-9.

- Togeby, Knud [in Danish]; Halleux, Pierre; Loth, Agnete, eds. (1880). Karlamagnús saga: branches I, III, VII et IX (in Old Norse and French). Traduction française par Annette Patron-Godefroit. Société pour l'étude de langue et de la littérature danoises. ISBN 9788774212614. (side-by-side edition and translation)

- Unger, Carl Richard, ed. (1860). Karlamagnús saga ok kappa hans (in Old Norse). Christiania: Trykt hos H.J. Jensen. (IArchive版; heimskringla.no版)

- (secondary sources)

- Farrier, Susan E., ed. (2019), The Medieval Charlemagne Legend: An Annotated Bibliography, Routledge, pp. 262–271, ISBN 9780429523922

- Gautier, Léon, ed. (1872). La Chanson de Roland. Vol. 2: Notes et variantes. Tours: Alfred Mame et Fils. pp. 114, 169.

- Langlois, Ernest (1904). Table des noms propres de toute nature compris dans les chansons de geste. Parils: Émille Bouillon.

- Ludlow, John Malcolm Forbes (1865), "V. Sub-cycle of the Peers: Ogier of Denmark", Popular epics of the middle ages of the Norse-German and Carlovingian Cycles, vol. 2, London: Macmillan, pp. 247–303

- Poulain-Gautret, Emmanuelle (2005). La tradition littéraire d'Ogier le Danois après le XIIIe siècle: permanence et renouvellement du genre épique médiéval. Paris: H. Champion. ISBN 9782745312082.

- Togeby, Knud (1969), Ogier le Danois dans les littérratures européennes, Munksgaard

- Voretzsch, Karl [in German] (1976) [1931]. Introduction to the Study of Old French Literature. Genève: Slatkine. pp. 208–210.