51°25′3″N 0°4′2″W / 51.41750°N 0.06722°W

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs are a series of sculptures of dinosaurs and other extinct animals, inaccurate by modern standards, in the London borough of Bromley's Crystal Palace Park. Commissioned in 1852 to accompany the Crystal Palace after its move from the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park, they were unveiled in 1854 as the first dinosaur sculptures in the world. The models were designed and sculpted by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins under the scientific direction of Sir Richard Owen, representing the latest scientific knowledge at the time. The models, also known as the Geological Court or Dinosaur Court, were classed as Grade II listed buildings from 1973, extensively restored in 2002, and upgraded to Grade I listed in 2007.

The models represent 15 genera of extinct animals, only three of which are true dinosaurs. They are from a wide range of geological ages, and include true dinosaurs, ichthyosaurs, and plesiosaurs mainly from the Mesozoic era, and some mammals from the more recent Cenozoic era. Today, the models are notable for representing the scientific inaccuracies of early palaeontology, the result of improperly reconstructed fossils and the nascent nature of the science in the 19th century,[1][2] with the Iguanodon and Megalosaurus models being particularly singled out.[3]

History

Following the closure of the Great Exhibition in October 1851, Joseph Paxton's Crystal Palace was bought and moved to Penge Place atop Sydenham Hill, South London, by the newly formed Crystal Palace Company.[lower-alpha 1] The grounds that surrounded it were then extensively renovated and turned into a public park with ornamental gardens, replicas of statues and two new man-made lakes. As part of this renovation, Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins was commissioned to build the first-ever life-sized models of extinct animals. He had originally planned to just re-create extinct mammals before deciding on building dinosaurs as well, which he did with advice from Sir Richard Owen, a celebrated anatomist and palaeontologist of the time.[5][6]

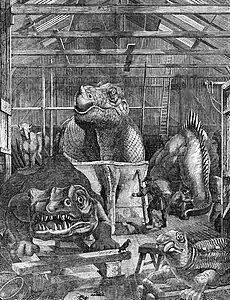

Hawkins set up a workshop on site at the park and built the models there. The dinosaurs were built full-size in clay, from which a mould was taken allowing cement sections to be cast. The larger sculptures are hollow with a brickwork interior.[7] There was also a limestone cliff to illustrate different geological strata.[8] The sculptures and the geological displays were originally referred to as "the Geological Court", since it was an extension of other exhibits made for the park that reconstructed historic art, including the Renaissance, Assyrian, and Egyptian Courts.[9][10]

The models were displayed on three islands acting as a rough timeline, the first island for the Palaeozoic era, a second for the Mesozoic, and a third for the Cenozoic. The models were given more realism by making the water level in the lake rise and fall, revealing different amounts of the dinosaurs.[11] To mark the launch of the models, Hawkins held a dinner on New Year's Eve 1853 inside the mould of one of the Iguanodon models.[12][13]

Hawkins benefited greatly from the public's reaction to the dinosaurs, which was so strong it allowed for the sale of sets of small versions of the dinosaur models, priced at £30 for educational use. But the building of the models was costly (having cost around £13,729) and in 1855, the Crystal Palace Company cut Hawkins's funding.[14] Several planned models were never made, while those half finished were scrapped, despite protest from sources including the Sunday newspaper, The Observer.[15]

Hawkins later worked on a "Palaeozoic Museum" in New York's Central Park, an American equivalent to the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs. In May 1871 many of the exhibits in Hawkins' workshop were destroyed by vandals and their fragments buried, possibly including elements of the original Elasmosaurus skeleton, which the American palaeontologist Edward Drinker Cope had loaned to Hawkins for preparation at the time.[16][17]

With progress in palaeontology, the reputation of the Crystal Palace models declined. In 1895, the American fossil hunter Othniel Charles Marsh scorned the dinosaurs' friends as doing them a great injustice, and spoke angrily of the models.[18] The models and the park fell into disrepair as the years went by, a process aided by the fire that destroyed the Crystal Palace itself in 1936, and the models became obscured by overgrown foliage. A full restoration of the animals was carried out in 1952 by Victor H.C. Martin,[19][20] at which time the mammals on the third island were moved to less well-protected locations in the park, where they were exposed to wear and tear. The limestone cliff was blown up in the 1960s.[21]

In 2001, the display was totally renovated. The destroyed limestone cliff was completely replaced using 130 large blocks of Derbyshire limestone, many weighing over 1 tonne (0.98 long tons; 1.1 short tons), rebuilt according to a small model made from the same number of polystyrene blocks.[21] Fibreglass replacements were created for the missing sculptures, and badly damaged parts of the surviving models were recast. For example, some of the animals' legs had been modelled in lead, fixed to the bodies with iron rods; the iron had rusted, splitting the lead open.[21]

The models and other elements of Crystal Palace Park were classed as Grade II listed buildings from 1973. The models were extensively restored in 2001, and upgraded to Grade I listed in 2007.[22][23]

In 2018, the Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs ran a crowd funding campaign, endorsed by the guitarist Slash, to build a permanent bridge to Dinosaur Island.[24][25] The bridge was designed by Tonkin Liu with engineering by Arup. The bridge swings on a pivot so it can be parked when not in use, to prevent unauthorised access. It was installed in January 2021.[26]

In May 2021, the nose and mouth of the Megalosaurus sculpture was given an emergency renovation, after it had fallen off the previous year.[27] Twenty-two new teeth and a 'prosthetic jaw' were installed on the sculpture. The renovation was funded by a grant from the Cultural Recovery Fund and fundraising from Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs.

The Dinosaur Park

Fifteen genera of extinct animals, not all dinosaurs, are represented in the park. At least three other genera (Dinornis, a mastodon, and Glyptodon) were planned, and Hawkins began to build at least the mastodon before the Crystal Palace Company cut his funding in 1855. An inaccurate map of the time shows planned locations of the Dinornis and mastodon.[28]

Palaeozoic era

The Palaeozoic era is represented in the park by the model rock exposure showing a succession of beds, namely the Carboniferous (including Coal Measures and limestone) and Permian.[29]

Crystal Palace's two Dicynodon models are based on incomplete Permian fossils found in South Africa, along with Owen's guess that they were similar to turtles, no evidence has been found to suggest Dicynodon had protective shells.[30]

Mesozoic era

The Mesozoic era is represented in the park by the model rock exposure showing a succession of beds, namely the Jurassic and Cretaceous, by models of dinosaurs and other animals known from mesozoic fossils, and by suitable vegetation – both living plants and models.[29]

Curiously, it is Hylaeosaurus, from the Cretaceous of England, not Iguanodon, that most resembles the giant iguana stereotype of early ideas of dinosaurs. The Hylaeosaurus in reality is much like Ankylosaurus – smallish quadrupedal herbivore with a knobbled armoured back, and spines along its sides. Hawkins's depiction is of a large Iguana-like beast with long sharp spines along its back, which Owen noted were "accurately given in the restoration [by Hawkins, to Owen's instructions, but] necessarily at present conjectural".[31]

The Ichthyosaurus models are based on Triassic or Jurassic fossils from Europe. Though the three ichthyosaurs are partly in water, they are implausibly shown basking on land like seals. Owen supposed they resembled crocodiles or plesiosaurs. Better fossil evidence shows that they have more in common with sharks and dolphins, having a dorsal fin and fish-like tail, whereas in Hawkins's models the tail is a flat protuberance from a straight backbone. A further discrepancy is that the models' eyes have exposed bony sclerotic plates, Owen conjecturing that with such large eyes they had "great powers of vision, especially in the dusk".[32] They became one of the three mascots of Crystal Palace Park, along with the Iguanodon and Megalosaurus (although ichthyosaurs are not dinosaurs). Coincidentally, the models more closely resemble more basic ichthyosaurs such as Cymbospondylus.[33]

The Iguanodon models represent fossils from the Jurassic and Cretaceous of Europe. Gideon Mantell sketched the original fossil, found in Sussex in 1822 by his wife, Mary Ann Mantell, as like a long slender lizard climbing a branch (on four legs), balancing with a whiplike tail; lacking a skull, he conjectured that the thumb bone was a nose horn.[34] The nose horn in particular is used repeatedly in popular textbooks and documentaries about dinosaurs to make fun of Victorian inaccuracies;[3] actually, even in 1854, Owen commented "the horn [is] more than doubtful".[35]

Three Labyrinthodon models were made for Crystal Palace, based on Owen's guess that, being amphibian in lifestyle, the Triassic animals might have resembled frogs; he named them Batrachia, from the Greek 'Batrachios', frog. One is smooth skinned and is based on the species "Labyrinthodon salamandroides" (Mastodonsaurus jaegeri); the other two were based on "Labyrinthodon pachygnathus" (Cyclotosaurus pachygnathus). Casts of Chirotherium footprints that Owen thought were made by the animals[36] were included in the ground around the models.[37]

Gigantic and visually impressive, the Megalosaurus became one of the park's three 'mascot dinosaurs' along with the Iguanodon and (less so) the Ichthyosaurs. Working from fragmentary evidence from Jurassic fossils found in England, consisting mainly of a hip and femur (thigh bone), with a rib and a few vertebrae, Owen conjectured the animal was quadrupedal; palaeontologists now believe it to have been bipedal (standing like Tyrannosaurus rex). The first suggestion that some dinosaurs might have been bipedal came in 1858, just too late to influence the model.[38]

When the models were built, only skulls of the Cretaceous fossil Mosasaurus had been discovered in the Netherlands, so Hawkins only built the head and back of the animal. He submerged the model deep in the lake, leaving the body unseen and undefined.[39] The Mosasaurus at Crystal Palace is positioned in an odd place near the secondary island that was originally a waterfall, and much of it is not visible from the lakeside path.

The three Plesiosaurus models represents three species of marine reptile, P. macrocephalus, P. dolichoderius and P. hawkinsii, from the Jurassic of England. Two of them have implausibly-flexible necks.[40]

Owen noted that the Pterodactylus fossils from the Jurassic of Germany had scales, not feathers, and while "somewhat bird-like" they had conical teeth, suggesting they were predatory. The two surviving models are perched on a rock outcrop; there were originally two more 'pterodactyls of the Oolite'.[41] The surviving models represent Pterodactylus cuvieri (= Cimoliopterus cuvieri), whereas the two other lost pterodactyl models represent Pterodactylus bucklandi (= Dolicorhamphus bucklandi). The latter species was poorly known based on fossil remains and explains why their designs were more based on Pterodactylus antiquus.[42][43]

Owen correctly identified Teleosaurus as similar to gharials, being slender Jurassic Crocodilians with very long thin jaws and small eyes, inferring from the sediment in which they were found that they were "more strictly marine than the crocodile of the Ganges [the gharial]."[44]

Cenozoic era

Anoplotherium commune is an extinct mammal species from the late Eocene to earliest Oligocene epochs, first found near Paris. Hawkins's models draw on Owen's speculation about its camel-like appearance. Three models were made, forming a small herd.[45] Hawkins seemingly closely followed George Cuvier's reconstructions of A. commune, giving it short or naked hair following Cuvier's view that its anatomy implied an aquatic lifestyle. Hawkins deviated from Cuvier by making it look more camel-like with small lips, small and rounded ears, a sloping skull, and four toes on each foot. These errors are the result of Hawkins' overreliance on camelids as an analogue for anoplotheriids. Anoplotherium is today thought to have used its robust build and long tail for bipedal browsing.[46]

Confusion between whether the A. commune sculptures were of A. gracile (= Xiphodon gracilis) is common, resulting from 19th-century guidebooks listing both species as present on the Tertiary Island. A. gracile was another fossil species studied by Cuvier; it was later determined to be of a distinct genus Xiphodon. Today, the sculptures of the three animals are confirmed to be of A. commune, but the "Megaloceros" fawn has been identified as a misplaced statue of A. gracile. An 1854 illustration reveals that there were once four A. gracile sculptures, three of which were lost and one of which remains. The body of the sculpture appears more heavily inspired by camelids than A. commune with a gracile muscle build.[46]

Megaloceros giganteus or Irish Elk is a species from the Pliocene to Pleistocene epochs in Eurasia. Hawkins built four Megaloceros sculptures, two male and two female. One sculpture of a doe was lost, leaving just three sculptures today. The adult male's antlers were made from actual fossil antlers, long since replaced. Moved from the third island, they had fallen into disrepair as they were easily reached by vandals. With their original but fragile antlers, the Irish Elks were the most accurate of the Cenozoic models; since they are of recent geological age (dying out 11,000 years ago), Hawkins was able to model them on living deer.[47][46]

The giant ground sloth Megatherium is from the Pliocene to Pleistocene epochs in South America, where Charles Darwin had excavated some fossils in 1835. The model was built hugging a live tree which subsequently grew and broke the model's arm. The arm was replaced and later the tree died. The model depicts the sloth as having a short trunk like a tapir, something the real animal never had. This model used to be in the children's zoo which has now been demolished.[48]

The models of Palaeotherium represent an extinct Eocene mammal thought by Georges Cuvier to be tapir-like. Three species were represented by each individual sculpture: the small-size P. minor (= Plagiolophus minor), the medium-size P. medium, and the largest and most robust-appearing P. magnum, all of which were studied by Cuvier. They have suffered the most wear and tear of all of the models, and the standing model no longer looked much like the original made by Hawkins. During the 1960s these models were lying discarded in the bushes about fifty yards from the original site and, prior to the 2002 restoration, they were in such bad shape that they were removed and put into store.[46][49] Some sources state that these models were added at a later date, but an Illustrated London News illustration of Hawkins's workshop shows them in the background.[50] A replica of P. magnum was commissioned by the Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs and built by palaeoartist Bob Nicholls, and unveiled to the public on 2 July 2023.[51]

Models of the "fearfully great bird" Dinornis of New Zealand (extinct by 1500 AD), and of the extinct elephant-like Mastodon (or Deinotherium of the Miocene and Pliocene of Eurasia and Africa), were planned for the 'Tertiary Islands' but not completed.[52]

In culture

Charles Dickens's 1853 novel, Bleak House, begins with a description of muddy streets, whose primordial character is emphasized by a dinosaur in the streets of London:

"Implacable November weather. As much mud in the streets as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling[lower-alpha 2] like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill."[53]

In H. G. Wells's 1905 novel Kipps, Kipps and Ann visit Crystal Palace and sit "in the presence of the green and gold Labyrinthodon that looms so splendidly above the lake" to discuss their future. There is a brief description of the dinosaurs and their surroundings and the impact they have on the characters.[54] Several of E. Nesbit's children's books feature the Crystal Palace dinosaur sculptures coming to life, including The Enchanted Castle (1907). The 1932 novel Have His Carcase, by Dorothy L. Sayers, has the character Lord Peter Wimsey mention the "antediluvian monsters" of the Crystal Palace.[55] Ann Coates's 1970 children's book Dinosaurs Don't Die, illustrated by John Vernon Lord, tells the story of a young boy who lives near Crystal Palace Park and discovers that Hawkins' models come to life; he befriends one of the Iguanodon and names it 'Rock' and they visit the Natural History Museum.[56]

The travel writer Paul Theroux mentions the dinosaurs in his 1989 novel My Secret History. The novel's narrator, Andre Parent, accidentally learns of his wife's infidelity when his young son, Jack, reveals that he has visited the dinosaurs in the company of his mother's 'friend' during Andre's prolonged absence gathering material for a travel book.[57] The title story in Penelope Lively's 1991 novel Fanny and the Monsters is about a Victorian girl who visits the Crystal Palace dinosaurs and becomes fascinated by prehistoric creatures.[58]

George Baxter, a pioneer of colour printing, made a well-known engraving which imagines Crystal Palace, set in its landscaped grounds with tall fountains and the dinosaurs in the foreground, before the 1854 opening.[59] In 2023, Historic England created three-dimensional photogrammetric models of the 29 sculptures.[60] The models can be viewed online.[61]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ An audio guide is available for visitors.[4] The nearest entrance to the audio trail start is the Penge entrance, close to Penge West station.

- ↑ The Megalosaurus was at that time thought to be quadrupedal, and was modelled that way by Hawkins.

References

- ↑ PaperTiger. "Crystal Palace Dinosaurs". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ↑ Roswell, Faith (3 January 2018). "The Victorian Dinosaur Park that Survived National Ridicule". Messy Nessy Chic. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- 1 2 Smith, Dan (26 February 2001). "A site for saur eyes". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ↑ "Darwin and the Dinosaurs audio trail". Audio Trails.

- ↑ "Natural History Pioneers: Richard Owen". Natural History Museum. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ↑ Hawkins, B. Waterhouse (1854). "On visual education as applied to geology". The Journal of the Society of Arts. 2 (78): 443–458. ISSN 2049-7865.

- ↑ Ireland, Libby (13 May 2016). "How were the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs made? – Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs". Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ↑ "Dinosaurs at Crystal Palace: Welcome to Victorian Park". YouTube.

- ↑ Witton & Michel, 2022. pp. 8–20

- ↑ Witton & Michel, 2022. pp. 21–38

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, pp. 13–17.

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, pp. 19–24.

- ↑ "Clift, Darwin, Owen and the Dinosauria...(2)". The Linnean. 7 (1): 8–14. January 1991.

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, pp. 25–31.

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Sachs, S. (2005). "Redescription of Elasmosaurus platyurus, Cope 1868 (Plesiosauria: Elasmosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous (lower Campanian) of Kansas, U.S.A". Paludicola. 5 (3): 92–106.

- ↑ Everhart, M. J. (2017). "Captain Theophilus H. Turner and the Unlikely Discovery of Elasmosaurus platyurus". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 120 (3–4): 233–246. doi:10.1660/062.120.0414. S2CID 89988230.

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, p. 85.

- ↑ Wyncoll, Keith (2011). LondonGAP Feb 2011 update.

- ↑ "Conservation of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs". Crystal Palace Matters. Summer 2013 (69). 2013.

- 1 2 3 Morton, Edward (July 2002). "Supporting Columns: Dinosaurs at Crystal Palace Park". Institute of Historic Building Conservation (IHBC). Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ↑ "Dinosaurs given protected status". BBC. 7 August 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ↑ Vaughan, Richard (7 August 2007). "Hodge upgrades Crystal Palace Park dinosaurs to Grade I status". Architects Journal. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ↑ O'Byrne Mulligan, Euan (2018). "Rock legend Slash backs Crystal Palace dinosaur campaign". Your Local Guardian. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ↑ "£30,000 Funding Boost brings South London's own 'Jurassic Park' one step closer!". Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs.

- ↑ Ravenscroft, Tom (31 March 2021). "Tonkin Liu creates swing bridge to access Crystal Palace's Dinosaur Island". De Zeen. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ↑ "Famous Crystal Palace dinosaur given emergency facelift". BBC News. 18 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, pp. 32, 85.

- 1 2 McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, p. 55.

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Bowden, A.J.; Tresise, G.R.; Simkiss, W. (2010). "Chirotherium, the Liverpool footprint hunters and their interpretation of the Middle Trias environment". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 343 (1): 209–228. Bibcode:2010GSLSP.343..209B. doi:10.1144/SP343.12. S2CID 128598979.

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, pp. 70, 74–75.

- ↑ Witton & Michel, 2022. pp. 96–103

- ↑ O'Sullivan, Michael; Martill, David (2018). "Pterosauria of the Great Oolite Group (Middle Jurassic, Bathonian) of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, England". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 63. doi:10.4202/app.00490.2018.

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, p. 79.

- 1 2 3 4 Witton & Michel, 2022. pp. 68–91

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, pp. 82–83.

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ "Plate 10: Mammals under repair (1999)". Nyder. 2003. Archived from the original on 24 November 2006. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, pp. 12, 78, citing the Illustrated London News, January 1854.

- ↑ https://cpdinosaurs.org/projects/palaeotherium-magnum

- ↑ McCarthy & Gilbert 1994, p. 32.

- ↑ Dickens, Charles (1853). Bleak House. Bradbury & Evans. p. 1. ISBN 1-85326-082-7.

- ↑ Wells, H. G. (1905). Kipps: The Story of a Simple Soul. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 384.

- ↑ Sayers, Dorothy L. "4". Have His Carcase. Victor Gollancz.

- ↑ Coates, Ann (1970). Dinosaurs Don't Die. Viking Children's Books. ISBN 0-7226-5757-9.

- ↑ Theroux, Paul (1989). My Secret History. Penguin. ISBN 9780241950494.

- ↑ Lively, Penelope (1991). Fanny and the Monsters. Mammoth. ISBN 978-0749706005.

- ↑ "Original Baxter Oil Print". Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ↑ "Crystal Palace Park dinosaurs turned into interactive 3D models". BBC. 18 September 2023. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ↑ "Crystal Palace Dinosaurs". Historic England. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

Sources

- McCarthy, Steve; Gilbert, Mick (1994). The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs: The Story of the World's First Prehistoric Sculptures. Crystal Palace Foundation. ISBN 978-1-897754-03-0.

- Witton, Mark P.; Michel, Ellinor (2022). The Art and Science of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs. The Crowood Press. ISBN 9780719840494.

Further reading

- Owen, R. (1854). Geology and Inhabitants of the Ancient World. Vol. 8. London: Crystal Palace library. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-166-91304-5.

- Kerley, Barbara (2001). The Dinosaurs of Waterhouse Hawkins: An Illuminating History of Mr. Waterhouse Hawkins, Artist and Lecturer. Caldecott Honor Book. Illustrated by Brian Selznick. Scholastic Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-439-11494-3.

External links

- Gibbs, Barry (8 August 2004). "The Dinosaurs". BBC.

- Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs – charity group which helps maintain the sculptures

- Crystal Palace Dinosaurs on YouTube, after the 2016 conservation work

.JPG.webp)