| Culgaith | |

|---|---|

An old Cumbrian farmhouse in Culgaith | |

| Population | 826 (2011)[1] |

| OS grid reference | NY6129 |

| Civil parish |

|

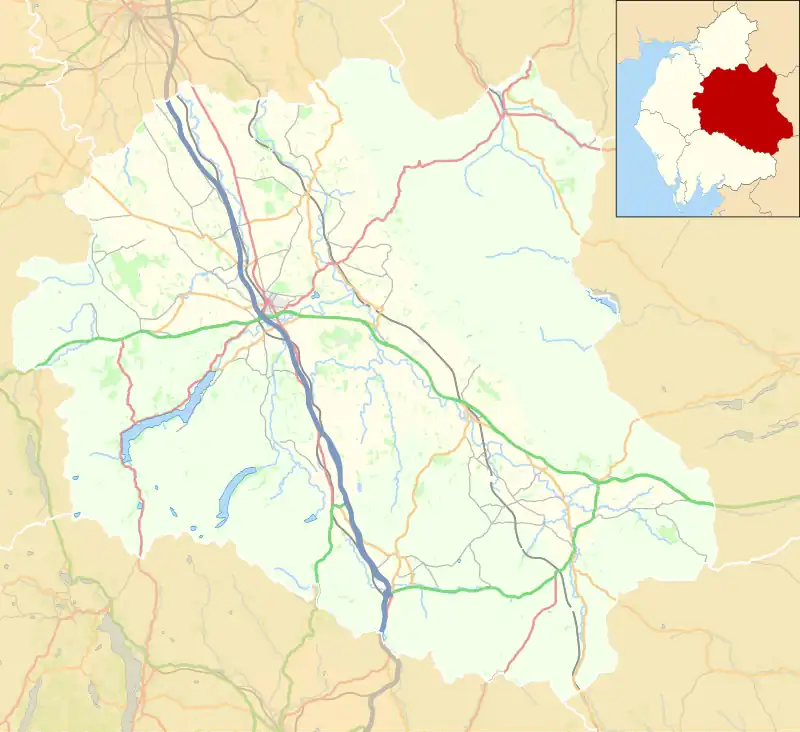

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | PENRITH |

| Postcode district | CA10 |

| Dialling code | 01768 |

| Police | Cumbria |

| Fire | Cumbria |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

Culgaith is a village and civil parish in the Eden district of Cumbria, England. It is located on the River Eden, between Temple Sowerby and Langwathby. At the 2001 census the parish had a population of 721,[2] increasing to 826 at the 2011 Census.[1]

Amenities include All Saints Church,[3] and its associated primary school,[4] as well as a pub. The village had a railway station, which closed in 1970.

Etymology

"This name is of most likely Brythonic origin. It is formed from an Old Celtic base *cūl, which has developed into Welsh 'cil', 'corner, retreat,' and British *koid, Welsh coed, 'wood'. The Old English form of the name would have been Cȳlcēt."[5] The first element might also be *cǖl, 'narrow', which would give Culgaith the same etymology as Culcheth.[6]

Culgaith is less likely to be derived from Gaelic *cid gaoit or *cil gaoit, meaning 'at the back of the wind' and 'windy nook', respectively.[7]

History

_geograph-3117548-by-Ben-Brooksbank.jpg.webp)

The village probably took its name from Henry de Culgaith, Clerk, who received a grant of lands in Carlisle, the local see, in vico Francorum. In circa 1296, his widow Alice de Culgaith quitclaimed the dower held of Holm Abbey which included her late husband's fee farm for rents.[8]

There was originally a chapel of Latin Christendom, attached to a mother church at Kirkland.[9][10] However, at the time, the Lord of the Manor in Moieties of Land was Sir Michael de Hercla, later Earl of Carlisle. He fought alongside King Edward I in the Scottish wars of independence, and was present at the siege of Caerlaverock Castle in 1300. The Earl fell foul of the King, and was attained and sent to the dungeon at Carlisle. The Manor was alienated to Sir Hugh Monceby, a brave knight.

Lady Knyvett inherited the estates of the Morricebys and Pickerings at Culgaith. Sir Michael's son and heir Sir Andrew de Hercla further angered the new King Edward II, who ordered his execution at Carlisle in 1327, supposedly the year of his own demise.[11] Nonetheless, the wood, Kirklandres, at Culgaith Manor, was conveyed to the monks at York. During the Wars of the Roses, the Manor was transferred to the Priory of Carlisle, with the church and chapel of ease.[12]

A grammar school was founded at the heart of the village opposite the parish church, for the parishes of Culgaith and Blencarn. Lands at Culgaith was used to found the Barton Grammar School. Before his death in 1443 he conveyed the manor to Hugh Salkeld.[13] By the census of 1811, the population of the area was grouped within the parish with the townships of Kirkland, Blencarn, and Skirwith.

There were 141 houses and 608 inhabitants in the chapelry, under the superior township of Skirwith. The population did not grow significantly until the 1960s. During the previous hundred years, Culgaith increased by only four people. During the industrial revolution the parish was distinctly agricultural, of which 3,052 acres were arable, 4625 were grazing pasture, and unbelievably, only 16 acres were woods in the whole of Kirk to Linton.[14]

Railway

Culgaith was served by a railway station, which opened in 1880 and closed down in May 1970.

Notable people

- Canadian politician Matthew Kendal Richardson, was born in Culgaith.[15]

- The former head coach for the England Rugby Football Union, Stuart Lancaster, was born in Culgaith.

See also

References

- 1 2 UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Culgaith Parish (E04002529)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ↑ UK Census (2001). "Local Area Report – Culgaith Parish (16UF020)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ↑ "Culgaith All Saints Church".

- ↑ "Culgaith School".

- ↑ Armstrong, A. M.; Mawer, A.; Stenton, F. M.; Dickens, B. (1950–52). The place-names of Cumberland. English Place-Name Society, vol.xx. Vol. Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 185.

- ↑ "The Brittonic Language in the Old North" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- ↑ James B., Johnston. The Place-Names of England and Wales. p. 225.

- ↑ Bishop of Carlisle, Register

- ↑ Daniel Lysons and Samuel Lysons, 'General history: Civil and ecclesiastical divisions', in Magna Britannia: Volume 4, Cumberland (London, 1816), pp. xxviii-xxxi. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/magna-britannia/vol4/xxviii-xxxi.

- ↑ T.Cadell & W.Davies (eds.), Magna Britannia, vol.IV, Cumberland (London, 1816)

- ↑ the fate of this family is told in the Chronicle of Lanercost Abbey.

- ↑ C139/112/61; Cumberland and Westmorland. Antiquarian and Archaeological Society n.s. xxxiii. 53; Calendar of Pipe Rolls, 1429-36, p. 116.

- ↑ C139/112/61; Cumberland and Westmoreland. Antique and Archaeological Society n.s. xxxiii. 53; Calendar Pipe Rolls, 1429-36, p. 116.

- ↑ 'Kirkdale - Kirk-Linton', in A Topographical Dictionary of England, ed. Samuel Lewis (London, 1848), pp. 697-701. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/topographical-dict/england/pp697-701.

- ↑ "PARLINFO - Parliamentarian File - Federal Experience - RICHARDSON, Matthew Kendal". Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2011.

- Sources

Quick, Michael (2009) [2001]. Railway passenger stations in Great Britain: a chronology (4th ed.). Oxford: Railway & Canal Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-901461-57-5. OCLC 612226077.

External links

- Cumbria County History Trust: Culgaith (nb: provisional research only – see Talk page)

- Listed Buildings of Cumbria