The Culture of ancient Illyria or Illyrian culture begins to be distinguished by increasingly clear features during the Middle Bronze Age and especially at the end of the Late Bronze Age. Ceramics as a typical element is characterized by the extensive use of shapes with two handles protruding from the edge as well as decoration with geometric motifs. At this time the first fortified settlements were established. The local metallurgy produced various types of weapons on the basis of Aegean prototypes with an elaboration of artistic forms. The main tools were the axes of the local types "Dalmato-Albanian" and "Shkodran", as well as the southern type of double ax. Spiritual culture is also expressed by a burial rite with mounds (tumuli) in which a rich material of archaeological artifacts has been found.[1][2][3][4]

Overview

Illyrian language

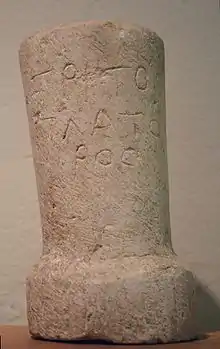

The Illyrian language was an Indo-European language or group of languages spoken by the Illyrians in Southeast Europe during antiquity. The language is unattested with the exception of personal names and placenames. Just enough information can be drawn from these to allow the conclusion that it belonged to the Indo-European language family. In ancient sources, the term "Illyrian" is applied to a wide range of tribes settling in a large area of southeastern Europe, including Ardiaei, Autariatae, Delmatae, Dassareti, Enchelei, Labeatae, Pannonii, Parthini, Taulantii and others (see list of ancient tribes in Illyria). It is not known to what extent all of these tribes formed a homogeneous linguistic group, but the study of the attested eponyms has led to the identification of a linguistic core area in the south of this zone, roughly around what is now Albania and Montenegro, where Illyrian proper is believed to have been spoken.

Little is known about the relationships between Illyrian and its neighboring languages. For lack of more information, Illyrian is typically described as occupying its own branch in the Indo-European family tree. A close relationship with Messapic, once spoken in southern Italy, has been suggested but remains unproven. A relationship with Venetic and Liburnian has also been discussed but is now rejected by most scholars. Among modern languages, Albanian is often conjectured to be a surviving descendant of Illyrian, although this too remains unproven.

In the early modern era and up to the 19th century, the term "Illyrian" was also applied to the modern South Slavic language of Dalmatia, today identified as Serbo-Croatian. This language is only tangentially related to ancient Illyrian as they share the theorized common ancestor, Proto-Indo-European; the two languages were never in contact as Illyrian had become extinct before the Slavic migrations to Southeastern Europe with possible exception to the ancestor of Albanian.[6][7][8][9][10]

Illyrian religion

The Illyrians, as most ancient civilizations, were polytheistic and worshipped many gods and deities developed of the powers of nature. The most numerous traces—still insufficiently studied—of religious practices of the pre-Roman era are those relating to religious symbolism. Symbols are depicted in every variety of ornament and reveal that the chief object of the prehistoric cult of the Illyrians was the Sun,[11][12] worshipped in a widespread and complex religious system.[11] The solar deity was depicted as a geometrical figure such as the spiral, the concentric circle and the swastika, or as an animal figure the likes of the birds, serpents and horses.[13][12] The symbols of water-fowl and horses were more common in the north, while the serpent was more common in the south.[12] Illyrian deities were mentioned in inscriptions on statues, monuments, and coins of the Roman period, and some interpreted by Ancient writers through comparative religion.[14][15] There appears to be no single most prominent god for all the Illyrian tribes, and a number of deities evidently appear only in specific regions.[14]

In Illyris, Dei-pátrous was a god worshiped as the Sky Father, Prende was the love-goddess and the consort of the thunder-god Perendi, En or Enji was the fire-god, Jupiter Parthinus was a chief deity of the Parthini, Redon was a tutelary deity of sailors appearing on many inscriptions in the coastal towns of Lissus, Daorson, Scodra and Dyrrhachium, while Medaurus was the protector deity of Risinium, with a monumental equestrian statue dominating the city from the acropolis. In Dalmatia and Pannonia one of the most popular ritual traditions during the Roman period was the cult of the Roman tutelary deity of the wild, woods and fields Silvanus, depicted with iconography of Pan. The Roman deity of wine, fertility and freedom Liber was worshipped with the attributes of Silvanus, and those of Terminus, the god protector of boundaries. Tadenus was a Dalmatian deity bearing the identity or epithet of Apollo in inscriptions found near the source of the Bosna river. The Delmatae also had Armatus as a war god in Delminium. The Silvanae, a feminine plural of Silvanus, were featured on many dedications across Pannonia. In the hot springs of Topusko (Pannonia Superior), sacrificial altars were dedicated to Vidasus and Thana (identified with Silvanus and Diana), whose names invariably stand side by side as companions. Aecorna or Arquornia was a lake or river tutelary goddess worshipped exclusively in the cities of Nauportus and Emona, where she was the most important deity next to Jupiter. Laburus was also a local deity worshipped in Emona, perhaps a deity protecting the boatmen sailing.[16]

It seems that the Illyrians did not develop a uniform cosmology on which to center their religious practices.[12] A number of Illyrian toponyms and anthroponyms derived from animal names and reflected the beliefs in animals as mythological ancestors and protectors.[17] The serpent was one of the most important animal totems.[18] Illyrians believed in the force of spells and the evil eye, in the magic power of protective and beneficial amulets which could avert the evil eye or the bad intentions of enemies.[11][14] Human sacrifice also played a role in the lives of the Illyrians.[19] Arrian records the chieftain Cleitus the Illyrian as sacrificing three boys, three girls and three rams just before his battle with Alexander the Great.[20] The most common type of burial among the Iron Age Illyrians was tumulus or mound burial. The kin of the first tumuli was buried around that, and the higher the status of those in these burials the higher the mound. Archaeology has found many artifacts placed within these tumuli such as weapons, ornaments, garments and clay vessels. The rich spectrum in religious beliefs and burial rituals that emerged in Illyria, especially during the Roman period, may reflect the variation in cultural identities in this region.[21]

Nicetas of Remesiana

Nicetas (c. 335–414) was Bishop of Remesiana, (present-day Bela Palanka, Serbia), which was then in the Roman province of Dacia Mediterranea.[22] According to reliable sources of archaeo-musicology, including those British, French and Italian, Nicetas has written, “I am Dardanian” (Latin: “Dardanus sum”).[23]

Nicetas promoted Latin sacred music for use during the Eucharistic worship and reputedly composed a number of liturgical hymns, among which some twentieth-century scholars number the major Latin Christian hymn of praise, Te Deum, traditionally attributed to Ambrose and Augustine. He is presumed to be the missionary to the barbarian Thracian tribe of the Bessi.[24]

Lengthy excerpts survive of his principal doctrinal work, Instructions for Candidates for Baptism, in six books. They show that he stressed the orthodox position in trinitarian doctrine. They contain the expression "communion of saints" about the belief in a mystical bond uniting both the living and the dead in a certain hope and love. No evidence survives of previous use of this expression, which has since played a central role in formulations of the Christian creed. His feast day as a saint is on 22 June.[25]

Jerome

Jerome (/dʒəˈroʊm/; Latin: Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; Greek: Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; c. 342 – c. 347 – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian priest, confessor, theologian, and historian; he is commonly known as Saint Jerome.

Jerome was born at Stridon (Illyricum), a village near Emona on the border of Dalmatia and Pannonia.[26][27] He is best known for his translation of most of the Bible into Latin (the translation that became known as the Vulgate) and his commentaries on the whole Bible. Jerome attempted to create a translation of the Old Testament based on a Hebrew version, rather than the Septuagint, as Latin Bible translations used to be performed before him. His list of writings is extensive, and beside his Biblical works, he wrote polemical and historical essays, always from a theologian's perspective.[28]

Jerome was known for his teachings on Christian moral life, especially to those living in cosmopolitan centers such as Rome. In many cases, he focused his attention on the lives of women and identified how a woman devoted to Jesus should live her life. This focus stemmed from his close patron relationships with several prominent female ascetics who were members of affluent senatorial families.[29]

Due to Jerome's work, he is recognised as a saint and Doctor of the Church by the Catholic Church, and as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church,[30] the Lutheran Church, and the Anglican Communion. His feast day is 30 September (Gregorian calendar).

Saint Hieronymus, also contributed in the field of education, pedagogy and culture.[31][32] As a Christian scholar he detailed his pedagogy of girls in numerous letters throughout his life. He did not believe the body in need of training, and thus advocated for fasting and mortification to subdue the body.[32] He only recommends the Bible as reading material, with limited exposure, and cautions against musical instruments. He advocates against letting girls interact with society, and of having "affections for one of her companions than for others."[32] He does recommend teaching the alphabet by ivory blocks instead of memorization so "She will thus learn by playing."[32] He is an advocate of positive reinforcement, stating "Do not chide her for the difficulty she may have in learning. On the contrary, encourage her by commendation..."[32]

Drilon-Mati-Glasinac culture

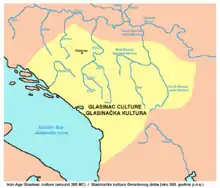

The Drilon-Mati-Glasinac culture is an archaeological culture, which first developed during the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age in the western Balkan Peninsula in an area which encompassed much of modern Albania to the south, Kosovo to the east, Montenegro, southeastern Bosnia and Herzegovina and parts of western Serbia to the north. It is named after the Glasinac and Mati type site areas, located in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Albania respectively.

The Glasinac-Mati culture represents both continuity of middle Bronze Age practices in the western Balkans and innovations specifically related to the early Iron Age. Its appearance coincides with a population boom in the region as attested in numerous new sites which developed in that era. One of the defining elements of Glasinac-Mati is the use of tumuli burial mounds as a method of inhumation. Iron axes and other weapons are typical items found in the tumuli of all subregional variations of Glasinac-Mati. As it expanded and fused with other similar material cultures it came to encompass the area which was known in classical antiquity as Illyria.[33]

Komani-Kruja culture

The Komani-Kruja culture is an archaeological culture attested from late antiquity to the Middle Ages in central and northern Albania, southern Montenegro and similar sites in the western parts of North Macedonia. It consists of settlements usually built below hillforts along the Lezhë (Praevalitana)-Dardania and Via Egnatia road networks which connected the Adriatic coastline with the central Balkan Roman provinces. Its type site is Komani and its fort on the nearby Dalmace hill in the Drin river valley. Kruja and Lezha represent significant sites of the culture. The population of Komani-Kruja represents a local, western Balkan people which was linked to the Roman Justinianic military system of forts. The development of Komani-Kruja is significant for the study of the transition between the classical antiquity population of Albania to the medieval Albanians who were attested in historical records in the 11th century.[34][35][36]

Illyrian art

During the Bronze Age, a number of Illyrian and Ancient Greek tribes started to emerge itself on the territory of Albania and established several artistic centers at the same time. Terracotta was widely used by both cultures most notably for reliefs and other architectural purposes. Quite a number of terracotta figures, among others from the Illyrians, were found near Belsh but besides that as well throughout Albania.[37][38][39]

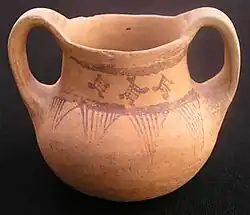

The art of pottery flourished also during that period and is considered amongst the most distinctive art produced from antiquity.[40] Various symbols, rituals, language and folklore were embodied in pottery art. Devollian pottery, named after the Devoll Valley, was made by the Illyrians.[41] Pottery of Illyrians consisted initially of geometric patterns like circles, squares, diamonds and other similar motifs and was nonetheless later influenced by Ancient Greek pottery.[42][43]

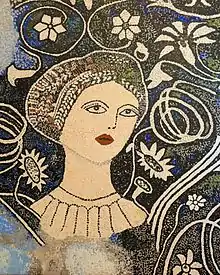

From earliest times mosaics have been used to cover floors in principal rooms of buildings, palaces, and tombs, as well as in the formal rooms of private houses. The use of mosaic became widespread in Illyria and Ancient Greek colonies within the Illyrian coast on the Adriatic and the Ionian Sea. The earliest examples of mosaic flooring date to the ancient period are housed in Apollonia, Butrint, Tirana, Lin, and Durrës.[44][45]

The Beauty of Durrës, the earliest mosaic discovered in Albania, is a polychromatic mosaic of the 4th century BC mainly made of multicolored pebbles.[46] It has a marvelous grace of its figure and great excellence of artistic creativity.[47][46] The 9 m2 (97 sq ft) mosaic is elliptical in shape and depicts a woman's head on a black background, surrounded by flowers and other floral elements.[46] It was discovered in 1918 in Durrës, and since 1982 has been on display at the National Historical Museum of Albania in Tirana.

The Roman period is marked by the production of sculptures presented as symbolic art. Roman sculpture was largely influenced by the sculptures of Greece and the Etruscan civilization whereas impressive examples can be mostly found in the cities of Apollonia and Butrint, which flourished during that period.

Daunian pottery

Daunian pottery was produced in the Daunia, today's Italian provinces of Barletta and Foggia. It was created by the Daunians, a tribe of the Iapygian civilization who had come from Illyria. Daunian pottery was mainly produced in the regional production centers of Ordona and Canosa di Puglia, beginning around 700 BC. The early paintings on the pottery show the vessels with geometric patterns. The ceramics were hand-formed, rather than thrown on a potter's wheel. They consisted of red, brown or black earth color applied with the decor. Diamonds, triangles, circles, crosses, squares, arcs, swastika and other forms of art were painted on them. The development of Daunian pottery forms is independent of the first Greek ceramics. Typical Daunian pottery include the Askos, hopper vessels and bowls with loop handles. Striking are often manual, or anthropomorphic Protomen to the sides and handles of the ceramics attached to or reproduced graphically.[48]

Messapian pottery

Messapian pottery is a type of Messapian ceramic, produced between the 7th century BC until the 3rd century BC on the Italian region of southern Apulia. Messapian pottery was made by the Messapii, an ancient people inhabiting the heel of Italy since around 1000 BC, who migrated from Crete and Illyria. Messapian pottery consisted first primarily, with geometric patterns like circles, squares, diamonds, horizontal dash patterns, swastika and other similar motifs. Late through Greek influence the meander was added.

Peucetian pottery

Peucetian pottery was a type of pottery made in the Apulian region of southern Italy by the Peucetians from the beginning of the 7th to the 6th centuries BC. It is an indigenous type. Its production area occupied the space between Bari and Gnathia. The pottery was painted only in brown and black and was characterized by geometrical ornaments, swastikas, diamonds, and horizontal and vertical lines.[49] These samples were mainly in the Late Geometric phase of ceramics (before 600 BC) with a close ornamental pattern. The second phase of the pottery since the 6th century BC is influenced strongly by the Corinthian vase painting.[50] This is reflected both in the ornaments, decorations in the form of radiation, as well as a change to figurative representation. The third and final phase brings a shift in production methods. The pottery was hand-formed before the arrival of the Greeks in the southernmost tip of Italy, when the potter's wheel was introduced. The painting became purely ornamental. Shown on them are decorative plants like ivy and laurel vines and palmettes. Rare images included figurative and mythological figures.

Devollian pottery

Devollian pottery, named after the Devoll Valley, was made by the Illyrians.[41] Pottery of Illyrians consisted initially of geometric patterns like circles, squares, diamonds and other similar motifs and was nonetheless later influenced by Ancient Greek pottery.[42][51]

Illyrian architecture

The beginnings of architecture in ancient Illyria dates back to the middle Neolithic Age with the discovery of prehistoric dwellings in Dunavec and Maliq.[52] They were built on a wooden platform that rested on stakes stuck vertically into the soil.[52] Prehistoric dwellings of Illyrians consist of three types such as houses enclosed either completely on the ground or half underground, both found in Cakran near Fier and houses constructed above ground.

During the Bronze Age, the Illyrians started to organize itself in their territory. Cities within Illyria were mainly built on the tops of high mountains surrounded by heavily fortified walls. Few monuments from the Illyrians are still preserved such as in Amantia, Antigonia, Byllis, Scodra, Lissus and Selca e Poshtme.[53]

During classical antiquity, cities and towns in Illyria have evolved from within the castle to include dwellings, religious and commercial structures, with constant redesigning of town squares and evolution of building techniques. Although there are prehistoric and classical structures, which effectively begins with constructions from the Illyrians such as in Byllis, Amantia, Phoenice, Apollonia, Butrint and Shkodër.[54][55] With the extension of the Roman Empire in the Balkans, impressive Roman architecture was built throughout the country whereas it is best exemplified in Durrës, Tirana and Butrint.

Following the Illyrian Wars, the architecture developed significantly in the 2nd century BC with the arrival of the Romans. The conquered settlements and villages such as Apollonia, Butrint, Byllis, Dyrrachium and Hadrianopolis were notably modernised following Roman models, with the building of a forum, roads, theatres, promenades, temples, aqueducts and other social buildings. The period also marks the construction of stadiums and thermal baths that were of social importance as places of gathering.

Dyrrachium thrived during the Roman period and became a protectorate after the Illyrian Wars. The Amphitheatre of Durrës, which the Romans built, was at that time the largest amphitheatre in the Balkan Peninsula.[56] It is the only Roman monument that survived up to the present.

The Via Egnatia, built by Roman Senator Gnaeus Egnatius, functioned for two millennia as a multi-purpose highway, which once connected the cities of Durrës on the Adriatic Sea in the west to Constantinople on the Marmara Sea in the east.[57] Further, the route gave the Roman colonies of the Balkans a direct connection to Rome.

Ships

The Illyrians were notorious sailors in the ancient world. They were great ship builders and seafarers. The most skillful Illyrian sailors were the Liburnians, Japodes, Delmatae and Ardiaei. The greatest navy was built by Agron in the 3rd century BC. There were different types of Illyrian ships, built for various uses. The main types of Illyrian ships were the Lembus, the Liburna, the Serilia liburnica and the Pristis.[58]

See also

Bibliography

- "Bashkia Belsh". qarkuelbasan.gov.al (in Albanian). Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- Beauchamp, Walters H. History of Ancient Pottery, Greek, Etruscan, and Roman, Volume 2 Publisher READ BOOKS, 2010 ISBN 1-4455-8060-8, ISBN 978-1-4455-8060-9

- Boederman, John, ed. (1924). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press, 1997. p. 230. ISBN 9780521224963.

- Bowden, William (2004). "Balkan Ghosts? Nationalism and the Question of Rural Continuity in Albania". In Christie, Neil (ed.). Landscapes of Change: Rural Evolutions in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1840146172.

- Brandt, J. Rasmus; Ingvaldsen, HÎkon; Prusac, Marina (2014). Death and Changing Rituals: Function and meaning in ancient funerary practices. Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-78297-639-4.

- Bury, John Bagnell; Cook, Stanley Arthur; Adcock, Frank Ezra (1996). The Cambridge Ancient History: The Augustan Empire, 43 B.C.-A.D. 69, 2nd ed., 1996 - Band 10 von The Cambridge Ancient History, Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen Edwards. University Press, 1996.

- Ceka, Neritan (2005), The Illyrians to the Albanians, Publ. House Migjeni, ISBN 99943-672-2-6

- Ceka, Neritan (2005). Apollonia: History and Monuments. Migjeni. p. 19. ISBN 9789994367252.

- Civici, N. (2007). "Analysis of Illyrian terracotta figurines of Aphroditeand other ceramic objects using EDXRF spectrometry†". X-Ray Spectrometry. 36 (2): 1. Bibcode:2007XRS....36...92C. doi:10.1002/xrs.945.

- Compayré, Gabriel (1892). The History of Pedagogy. D.C. Heath & Company.

- Demiraj, Shaban (1988). Gjuha shqipe dhe historia e saj. Shtëpia Botuese e Librit Universitar.

- Demiraj, Shaban (1996). Fonologjia historike e gjuhës shqipe. Akademia e Shkencave e Republikës së Shqipërisë.

- Demiraj, Shaban (1999). Prejardhja e shqiptarëve në dritën e dëshmive të gjuhës shqipe. Tiranë: Shtëpia Botuese "Shkenca". ISBN 99927-654-7-X.

- "Die Ekklesiale Geographie Albaniens bis zum Ende des 6. Jahrhunderts –Beiträge der Christlichen Archäologie auf dem Territorium der Heutigen Republik Albanien". kulturserver-hamburg.de (in German).

Die Bischofsstädte und ihre Einflussbereiche

- F. A. Wright (1934). ALEXANDER THE GREAT. London: GEORGE ROUTLEDGE SONS, LTD. pp. 63–64.

- Gloyer, Gillian (2015-01-07). Albania. Bradt Travel Guides, 2015. p. 87. ISBN 9781841628554.

- Hamp, Eric Pratt; Ismajli, Rexhep (2007). Comparative Studies on Albanian. Akademia e Shkencave dhe e Arteve e Kosovës. ISBN 978-9951-413-62-6.

- Hurschmann, Rolf Daunische Vasen. In: Der Neue Pauly (DNP). Band 3, Metzler, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-476-01473-8

- Ismajli, Rexhep (2015). Eqrem Basha (ed.). Studime për historinë e shqipes në kontekst ballkanik [Studies on the History of Albanian in the Balkan context] (PDF) (in Albanian). Prishtinë: Kosova Academy of Sciences and Arts, special editions CLII, Section of Linguistics and Literature.

- J. M. Coles; A. F. Harding (2014-10-30). Meine Bücher Mein Verlauf Bücher bei Google Play The Bronze Age in Europe: An Introduction to the Prehistory of Europe C.2000-700 B.C. Routledge, 2014. pp. 448–470. ISBN 9781317606000.

- Lafe, Emil, ed. (2008). "Fjalor Enciklopedik Shqiptar". (Encyclopedic Dictionary of Albania) (in Albanian). Vol. 2. Tiranë: Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë. pp. 977–978. ISBN 9789995610272. OCLC 426069353.

- Malkin, Irad (1998-11-30). The Returns of Odysseus: Colonization and Ethnicity. University of California Press, 1998. p. 77. ISBN 9780520920262.

- Maraval, Pierre (1998), Éditions Desclée de Brouwer (ed.), Petite vie de Saint Jérôme (in French), Paris (France), p. 66, ISBN 2-220-03572-7

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Nallbani, Etleva (1999–2000). "Disa objekte të hershme në kulturën e Komanit". Iliria (in Albanian). 29 (1–2): 297–305. doi:10.3406/iliri.1999.1718.

- Nallbani, Etleva (2017). "Early Medieval North Albania: New Discoveries, Remodeling Connections: The Case of Medieval Komani". In Gelichi, Sauro; Negrelli, Claudio (eds.). Adriatico altomedievale (VI-XI secolo) Scambi, porti, produzioni (PDF). Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia. ISBN 978-88-6969-115-7.

- "POLITISCHE ORGANISATIONSFORMEN IM VORRÖMISCHEN SÜDILLYRIEN" (PDF). fondazionecanussio.org (in German). p. 58.

Die Urbanisierung Illyriens begann im späten 5. Jh. mit den Stadtanlagen von Amantia, Klos und Kalivo und nahm im 4. Jh. mit Byllis, Lissos, Zgerdesh und Scodra großen Aufschwung

- Sear, Frank (1983). Roman Architecture - Cornell paperbacks. Cornell University Press, 1983. p. 270. ISBN 9780801492457.

- Stipčević, Aleksandar (1976). "Simbolismo illirico e simbolismo albanese: appunti introduttivi". Iliria (in Italian). 5: 233–236. doi:10.3406/iliri.1976.1234.

- Stipčević, Aleksandar (1977). The Illyrians: history and culture. Noyes Press, 1977. ISBN 9780815550525.

- Scheck, Thomas P. (2008). Commentary on Matthew. The Fathers of the Church. Vol. 117. ISBN 978-0-8132-0117-7.

- Šašel - Kos, M. 1997, The Roman Inscriptions in the National Museum of Slovenia, Situla 35.

- Ward, Maisie (1950). Saint Jerome. London: Sheed & Ward.

- West, Martin L. (2007). Indo-European Poetry and Myth. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199280759.

- Williams, Megan Hale (2006). The Monk and the Book: Jerome and the Making of Christian Scholarship. Chicago: U of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-89900-8.

- Wilkes, John J. (1992). The Illyrians. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-19807-5.

- United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization. "Archaeology and art of Albania, Ecuador, China, Bulgaria" (PDF). unesdoc.unesco.org. pp. 4–6.

References

- ↑ Lafe, Emil, ed. (2008). "Fjalor Enciklopedik Shqiptar". (Encyclopedic Dictionary of Albania) (in Albanian). Vol. 2. Tiranë: Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë. pp. 977–978. ISBN 9789995610272. OCLC 426069353.

- ↑ Ceka, Neritan (2005), The Illyrians to the Albanians, Publ. House Migjeni, ISBN 99943-672-2-6

- ↑ Jaupaj, Lavdosh (2019). Etudes des interactions culturelles en aire Illyro-épirote du VII au III siècle av. J.-C (Thesis). Université de Lyon; Instituti i Arkeologjisë (Albanie).

- ↑ Kurti, Rovena (2017). "On some aspects of the Late Bronze Age burial costume from north Albania". Proceedings of the International Conference "New Archaeological Discoveries in the Albanian Regions" 30-31, January, Tirana 2017.

- ↑ Ceka, Neritan (2005). Apollonia: History and Monuments. Migjeni. p. 19. ISBN 9789994367252. "In the third-second centuries BC, a number of Illyrians, including Abrus, Bato, and Epicardus, rose to the highest position in the city administration, that of prytanis. Other Illyrians such as Niken, son of Agron, Tritus, son of Plator, or Genthius, are found on graves belonging to ordinary families (fig.7)."

- ↑ Demiraj, Shaban (1988). Gjuha shqipe dhe historia e saj. Shtëpia Botuese e Librit Universitar.

- ↑ Demiraj, Shaban (1996). Fonologjia historike e gjuhës shqipe. Akademia e Shkencave e Republikës së Shqipërisë.

- ↑ Demiraj, Shaban (1999). Prejardhja e shqiptarëve në dritën e dëshmive të gjuhës shqipe. Tiranë: Shtëpia Botuese "Shkenca". ISBN 99927-654-7-X.

- ↑ Hamp, Eric Pratt; Ismajli, Rexhep (2007). Comparative Studies on Albanian. Akademia e Shkencave dhe e Arteve e Kosovës. ISBN 978-9951-413-62-6.

- ↑ Ismajli, Rexhep (2015). Eqrem Basha (ed.). Studime për historinë e shqipes në kontekst ballkanik [Studies on the History of Albanian in the Balkan context] (PDF) (in Albanian). Prishtinë: Kosova Academy of Sciences and Arts, special editions CLII, Section of Linguistics and Literature.

- 1 2 3 Stipčević 1977, p. 182.

- 1 2 3 4 Wilkes 1992, p. 244.

- ↑ Stipčević 1977, pp. 182, 186.

- 1 2 3 Wilkes 1992, p. 245.

- ↑ West 2007, p. 15.

- ↑ Šašel - Kos, M. 1997, The Roman Inscriptions in the National Museum of Slovenia, Situla 35. pages 127 - 131

- ↑ Stipčević 1977, p. 197.

- ↑ Stipčević, Aleksandar (1976). "Simbolismo illirico e simbolismo albanese: appunti introduttivi". Iliria (in Italian). 5: 233–236. doi:10.3406/iliri.1976.1234.

- ↑ Wilkes 1992, p. 123.

- ↑ F. A. Wright (1934). ALEXANDER THE GREAT. London: GEORGE ROUTLEDGE SONS, LTD. pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Brandt, Ingvaldsen & Prusac 2014, p. 249.

- ↑ "Letter of Pope John Paul II for the third centenary of the union of the Greek-Catholic Church of Romania with the Church of Rome".

- ↑ Dr Shaban Sinani & Eduard Zaloshnja (2004) Albanski kodeksi - The Codices of Albania. pages 161 - 170 in International Conference "Church Archives & Libraries" Collection of works from International conference Kotor 17th – 18th April 2002. Kotor 2004 (English & Montenegrin)

- ↑ "1994 | Gottfried Schramm: A New Approach to Albanian History". www.albanianhistory.net. Retrieved 2020-02-29.

- ↑ Martyrologium Romanum. Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2001. ISBN 88-209-7210-7; Gross, Ernie. This Day In Religion. New York:Neal-Schuman Publications, 1990. ISBN 1-55570-045-4.

- ↑ Scheck 2008, p. 5.

- ↑ Ward 1950, p. 7: "It may be taken as certain that Jerome was an Italian, coming from that wedge of Italy which seems on the old maps to be driven between Dalmatia and Pannonia."

- ↑ Schaff, Philip, ed. (1893). A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church. 2nd series. Vol. VI. Henry Wace. New York: The Christian Literature Company. Archived from the original on 11 July 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ↑ Williams 2006.

- ↑ In the Eastern Orthodox Church he is known as Saint Jerome of Stridonium or Blessed Jerome. "Blessed" in this context does not have the sense of being less than a saint, as it does in the West.

- ↑ Pierre Maraval (1998), Éditions Desclée de Brouwer (ed.), Petite vie de Saint Jérôme (in French), Paris (France), p. 66, ISBN 2-220-03572-7

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - 1 2 3 4 5 Compayré, Gabriel (1892). The History of Pedagogy. D.C. Heath & Company.

- ↑ Stipčević 1977, p. 108.

- ↑ Nallbani, Etleva (2017). "Early Medieval North Albania: New Discoveries, Remodeling Connections: The Case of Medieval Komani". In Gelichi, Sauro; Negrelli, Claudio (eds.). Adriatico altomedievale (VI-XI secolo) Scambi, porti, produzioni (PDF). Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia. ISBN 978-88-6969-115-7.

- ↑ Nallbani, Etleva (1999–2000). "Disa objekte të hershme në kulturën e Komanit". Iliria (in Albanian). 29 (1–2): 297–305. doi:10.3406/iliri.1999.1718.

- ↑ Bowden 2004, pp. 61, 220

- ↑ Civici, N. (2007). "Analysis of Illyrian terracotta figurines of Aphroditeand other ceramic objects using EDXRF spectrometry†". X-Ray Spectrometry. 36 (2): 1. Bibcode:2007XRS....36...92C. doi:10.1002/xrs.945.

- ↑ John Bagnell Bury; Stanley Arthur Cook; Frank Ezra Adcock (1996). The Cambridge Ancient History: The Augustan Empire, 43 B.C.-A.D. 69, 2nd ed., 1996 - Band 10 von The Cambridge Ancient History, Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen Edwards. University Press, 1996. ISBN 9780521264303.

- ↑ "Bashkia Belsh". qarkuelbasan.gov.al (in Albanian). Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- ↑ Aleksandar Stipčević (1977). The Illyrians: history and culture (Aleksandar Stipčević ed.). Noyes Press, 1977. ISBN 9780815550525.

- 1 2 Irad Malkin (1998-11-30). The Returns of Odysseus: Colonization and Ethnicity. University of California Press, 1998. p. 77. ISBN 9780520920262.

- 1 2 The Cambridge Ancient History (John Boederman ed.). Cambridge University Press, 1997. 1924. p. 230. ISBN 9780521224963.

- ↑ J. M. Coles; A. F. Harding (2014-10-30). Meine Bücher Mein Verlauf Bücher bei Google Play The Bronze Age in Europe: An Introduction to the Prehistory of Europe C.2000-700 B.C. Routledge, 2014. pp. 448–470. ISBN 9781317606000.

- ↑ Ferra, Ferik (2011). 4 shekuj para Krishtit. Tirana, Albania: Naimi. p. 64. ISBN 978-9928109101.

- ↑ Ferid Hudhri (2003). Albania Through Art. Tirana: Onufri. ISBN 978-9992753675.

- 1 2 3 Fjalori Enciklopedik Shqiptar, Akademia e Shkencave - Tiranë, 1984 (MOZAIKU I DURRËSIT ME PORTRETIN E NJE GRUAJE, page 726)

- ↑ BANK OF ALBANIA Coin with “The Beauty of Durrës” Archived 2012-03-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Rolf Hurschmann: Daunische Vasen. In: Der Neue Pauly (DNP). Band 3, Metzler, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-476-01473-8, pages. 335–336.

- ↑ History of Ancient Pottery, Greek, Etruscan, and Roman, Volume 2 Author H B Walters Publisher READ BOOKS, 2010 ISBN 1-4455-8060-8, ISBN 978-1-4455-8060-9 p. 328-329

- ↑ The Foundations of Roman Italy Publisher Ardent Media 1937 p.315

- ↑ J. M. Coles; A. F. Harding (2014-10-30). Meine Bücher Mein Verlauf Bücher bei Google Play The Bronze Age in Europe: An Introduction to the Prehistory of Europe C.2000-700 B.C. Routledge, 2014. pp. 448–470. ISBN 9781317606000.

- 1 2 United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization. "Archaeology and art of Albania, Ecuador, China, Bulgaria" (PDF). unesdoc.unesco.org. pp. 4–6.

- ↑ Gilkes, O., Albania An Archaeological Guide, I.B.Tauris 2012, ISBN 1780760698, p263

- ↑ "POLITISCHE ORGANISATIONSFORMEN IM VORRÖMISCHEN SÜDILLYRIEN" (PDF). fondazionecanussio.org (in German). p. 58.

Die Urbanisierung Illyriens begann im späten 5. Jh. mit den Stadtanlagen von Amantia, Klos und Kalivo und nahm im 4. Jh. mit Byllis, Lissos, Zgerdesh und Scodra großen Aufschwung

- ↑ "Die Ekklesiale Geographie Albaniens bis zum Ende des 6. Jahrhunderts –Beiträge der Christlichen Archäologie auf dem Territorium der Heutigen Republik Albanien". kulturserver-hamburg.de (in German).

Die Bischofsstädte und ihre Einflussbereiche

- ↑ Albania. Bradt Travel Guides, 2015. 2015-01-07. p. 87. ISBN 9781841628554.

- ↑ Frank Sear (1983). Roman Architecture - Cornell paperbacks. Cornell University Press, 1983. p. 270. ISBN 9780801492457.

- ↑ The Greek State at War, William Kendrick Pritchett, ISBN 0-520-07374-6, 1991, page 76, "Similarly the pirates on the Illyrian coast are said to have developed vessels that were named after their tribes, the lembus, pristis and liburna"