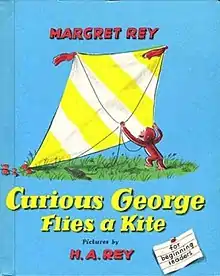

First edition | |

| Author | H. A. Rey Margret Rey |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Series | Curious George |

| Genre | Children's literature |

| Publisher | Houghton Mifflin |

Publication date | 1958[1] |

| Media type | |

| Preceded by | Curious George Gets a Medal |

| Followed by | Curious George Learns the Alphabet |

Curious George Flies a Kite is a children's book written for beginning readers by Margret Rey, illustrated by H. A. Rey, and published by Houghton Mifflin in 1958. It is the fifth book in the original Curious George series and the only one the Reys did not write together.

Plot

Curious George, left alone at home with his new ball, looks out the window and sees a small house. He jumps out the window, inside the house sees a lot of bunnies. He accidentally lets one out, plays hide and seek with the bunny, and lets it back in the house.

As George walks back home, he sees a fisherman fishing and is inspired to fish too. When he uses cake (for fishing bait), he catches no fish, even though the cake gets taken off the hook by the fish. After two failed attempts for catching the fish, he eats the rest of the cake (as he realized he loved cake too). Then, he tries another way to catch fish, but ends up falling into the water. The neighbor boy, Bill, helps him get out. He tells George that even though George did not catch any fish, the good news is that none of the fish ate him. Then Bill shows him his new kite. He lets George watch it while he gets his bicycle.

George flies the kite. At first, he thinks it would be okay to fly it. But when he tries that, the kite soon flies off with him. The Man with the Yellow Hat asks Bill if he saw George, and soon sees him up in the sky with the kite. The Man with the Yellow Hat (despite understanding Bill about the kite) did not wait to hear any more. In fact, he (thinking out loud) said he had to have George back, so the Man rescues him by helicopter. George returns the kite to Bill, who in return gives him the bunny.

Criticism and legacy

Daniel Greenstone, in an article published in the Journal of Social History, remarks on the book's placement in the series' publication history. It is the fifth in the series; the first three, in which George is kidnapped from Africa, taken to America, and engages in exciting and dangerous adventures, were written with an educational philosophy in which children (especially boys) were taught to be courageous and face dangers head-on, with "pluck". Given the authors' background (Margret and H. A. Rey were German Jews who fled the Nazis and escaped to Spain by bicycle, and then made their way to the United States), and the relatively old-fashioned educational attitudes of Europe in comparison to the US, this makes sense, according to Greenstone, but by the time of the fourth book (Curious George Gets a Medal, 1957), the authors were being more careful: George still has an adventure outside, but he only ventures out to clean up a mess he made, and his adventure prompts suspense, not fun and excitement. In the kite adventure, published the next year, Greenstone sees "a decisive turning point": he argues that "the Reys ceded important aspects of creative control to the experts who made up the pediatric and educational establishment". The following books have a more anxious central character who is more likely to stay at home. In Curious George Flies a Kite, the Man in the Yellow Hat warns George in the beginning of the story, and the adventures are "frightening, unsanctioned and unintentional": George is scared when the kite takes off with him. According to Greenstone, "the George stories have evolved from wild, vicarious thrills to a neutered, cautionary tale. Even something as innocuous as flying a kite turns out to be fraught with danger. The story ends with George returning the kite, which he exchanges for a baby bunny. The last page shows George playing tamely with the bunny indoors". From then on, in the book series, George plays indoors.[2]

Greenstone notes another set of events that influenced the content and the very language of the George series: by the late 1950s the Dr. Seuss books were being published, with their simplified vocabulary to aid the teaching of phonics; at that time also the Soviet launch of the Sputnik satellite promoted doubts about America's education system.[2] The Reys caught on, and the kite adventure has a vocabulary limited to 219 words. Margret Rey later acknowledged that this simplification had been a mistake.[3]

The book provided an image for the US Postal Service, which ran a series of stamps honoring children's books in 2013.[4]

References

- ↑ Dirda, Michael (September 6, 2016). "Curious George turns 75: Why the monkey and the Man in the Yellow Hat endure". The Washington Post.

- 1 2 Greenstone, Daniel (2005). "Frightened George: How the Pediatric-Educational Complex Ruined the Curious George". Journal of Social History. 39 (1): 221–28. doi:10.1353/jsh.2005.0103. JSTOR 3790536. S2CID 144081042.

- ↑ Jones, Dee (2010). "Retrospective Essay". The Curious George Complete Adventures: 70th Anniversary Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 401–14. ISBN 9780547346366.

- ↑ Springen, Karen (August 22, 2019). "U.S. Postal Service Celebrates Children's Books". Publishers Weekly.