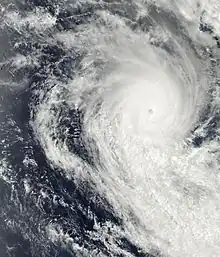

Cyclone Beni near its peak intensity on 29 January, between Vanuatu and New Caledonia | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 19 January 2003 |

| Dissipated | 5 February 2003 |

| Category 5 severe tropical cyclone | |

| 10-minute sustained (FMS) | |

| Highest winds | 205 km/h (125 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 920 hPa (mbar); 27.17 inHg |

| Category 4-equivalent tropical cyclone | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/JTWC) | |

| Highest winds | 230 km/h (145 mph) |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 1 total |

| Damage | $7 million (2003 USD) |

| Areas affected | Vanuatu, New Caledonia, Queensland |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 2002–03 South Pacific and Australian region cyclone seasons | |

Severe Tropical Cyclone Beni was an intense tropical cyclone that affected four countries, on its 18-day journey across the South Pacific Ocean during January and February 2003. The system originally developed during 19 January as a weak tropical disturbance within the monsoon trough, to the northeast of the Santa Cruz Islands. Over the next few days the system gradually developed further before it was classified as a tropical cyclone and named Beni during 24 January.

Originally, the storm moved slowly towards the west. Initially moving towards the west, the cyclone then made a clockwise loop, and turned south. Beni entered more conductive conditions and began to strengthen while moving southeast. After attaining winds of hurricane-force, Beni strengthened rather quickly. Traveling between Vanuatu and New Caledonia, Beni reached its peak intensity on January 29 with winds of 125 mph (205 km/h 10-minute sustained), and a peak pressure of 920 mbar (27 inHg) before rapidly weakening. The cyclone made its closest approach to the island of New Caledonia on January 30; shortly after that, Beni weakened into a tropical depression. In the Coral Sea, however, the storm once again entered more favorable conditions and it briefly re-intensified into. However, this trend was short-lived; wind shear took its toll on the cyclone, weakening it back down to a tropical depression. The remnants of Beni proceeded to make landfall near Mackay, Queensland and produce heavy rain over much of the drought stricken state of Queensland until finally dissipating on February 5.

The cyclone caused a food shortage and flooded portions of the Solomon Islands. Across the island group, about 2,000 people took shelter, some in caves. In addition, the storm brought storm surge and beach erosion to Vanuatu. New Caledonia faced power outages and heavy rains. In Queensland, Beni was responsible severe flooding. Two communities were isolated during the storm; a total of 160 people were also cut off by floodwater. The water level of one dam increased from 0.5% to 81%. The cyclone's heavy rains helped ease drought problems in Queensland; in fact, water reserves replenished five years worth of supply in one location. In all, one death was reported in Queensland and damages totaled to A$10 million (US$6 million, 2003 USD) in Queensland and US$1 million (A$2 million) in Vanuatu.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

Late on 19 January the Fiji Meteorological Service's Regional Specialized Meteorological Center in Nadi, Fiji (RSMC Nadi) started to monitor a tropical disturbance, that had developed within the monsoon trough to the northeast of the Santa Cruz Islands.[1] Over the next couple of days the disturbance developed into a tropical depression as it moved towards the west-southwest, within an area of favourable conditions for further development including low vertical wind shear and sea-surface temperatures of about 30 °C (86 °F).[1][2] As the system moved near the Solomon Island of San Cristóbal during 22 February, further development of the system had become suppressed by strengthening wind shear that exposed the systems low level circulation.[2][3] During 24 February as the system moved beneath an upper-level ridge of high pressure, the wind shear abated and convection developed over the systems consolidating low level circulation.[1][4][5] As a result, the United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center issued a Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert on the system later that day, before RSMC Nadi reported that the depression had developed into a category one tropical cyclone on the Australian tropical cyclone scale and named it Beni early on 24 January.[1][5] At around this time the JTWC initiated advisories on the system and designated it as Tropical Cyclone 12P, while it was located about 160 km (100 mi) to the south of the Solomon Island Rennell.[4][6]

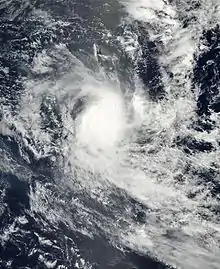

After being named Beni executed a small clockwise loop for two days to the southeast of Rennell, partially as a result of a strong surface ridge of high pressure to the south of the low level circulation center.[2] Environmental conditions surrounding the system also fluctuated during 25 January, as a result of Beni's position to the north of the strongly diffluent flow on the northern side of the upper-level ridge axis.[2] As a result, the systems low level circulation center became partially exposed with deep convection located to the west of the system before Beni's low-level circulation slipped back under the convection during 26 January, with spiral bands wrapping tightly around the centre.[1][2] As a result, RSMC Nadi reported that the system had developed into a category 2 tropical cyclone during that day.[1][3] Over the next two days conditions continued to fluctuate with shear playing a significant role in holding back further intensification of the system.[1] Early on 28 January as a ragged eye and cloud filled eye appeared on satellite imagery, the JTWC reported that the system had become equivalent to a category 1 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale (SSHWS).[1][7] When the data was reanalyzed, RSMC Nadi reported that Beni had become a category 3 severe tropical cyclone at this time, however, operationally it wasn't declared a category 3 severe tropical cyclone for another 18 hours.[1][4] Throughout 28 January Beni continued to intensify before the JTWC reported early the next day that the system had peaked, with 1-minute sustained wind speeds of 230 km/h (145 mph) which made it equivalent to a category 4 hurricane on the SSHS.[7] Later that day RSMC Nadi reported that Beni had explosively developed and peaked as a Category 5 severe tropical cyclone on the Australian scale, with 10-minute sustained winds of 205 km/h (125 mph).[1][4] At this time the system was moving to the southeast and was located about 400 km (250 mi) to the west of Port Vila, Vanuatu.[4]

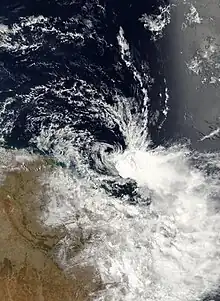

After peaking in intensity Beni subsequently started to weaken as a trough of low pressure increased vertical wind shear over the system, while an upper-level low started to develop to the west of New Caledonia.[2][4][8] However, a strengthening ridge slowed Beni down and allowed the cyclone to move towards the south and then southwest, moving it away from Vanuatu. Rapid dissipating due to wind shear, the cyclone's central dense overcast was soon completely separated from Beni's center of circulation. On 30 January, the storm passed south of New Caledonia and even closer to the commune of L'Île-des-Pins, but by this time, RSMC Nadi reported that Cyclone Beni was only a marginal Category 1 system with winds of 40 mph (65 km/h) and a pressure of 994 mbar (29.4 inHg). The system was further downgraded into a tropical depression the same day while located 240 nmi (445 km) southwest of New Caledonia. The depression continued to move towards the west, and subsequently northwest, across the Coral Sea, and on 1 February, the depression crossed 160°E and moved into the Australian region. In an area of once again increasing sea surface temperatures and warm air, convection developed over the center. TCWC Brisbane reported that the system was once again briefly upgraded into tropical cyclone status. At this time the pressure of the cyclone was 995 mbar (29.4 inHg). However, vertical wind shear once again took its toll on Beni, and the circulation center decoupled from the deep convection and the storm's strongest winds. Consequently, Beni was once again downgraded into a depression, just 12 hours after its re-classification as a tropical cyclone. The remnant low of Severe Tropical Cyclone Beni made landfall near Mackay on 5 February.

Preparations, impact, and aftermath

Solomon Islands

The cyclone impacted various Solomon Islands between 23 and 28 January, about a month after Cyclone Zoe had affected parts of the Temotu Province.[9][10] As Beni affected the islands various cyclone warnings were issued by the Solomon Island Meteorological Service, while inhabitants moved inland and sheltered in caves.[2][10]

Multiple crops in the Solomon Islands were damaged by the flooding rains, including coconut, papaya, banana, and sweet potato crops, causing a food shortage on the islands.[11] Saltwater inundation caused by strong waves damaged some garden plots, adding on further to the food shortage.[12] A freshwater lake was flooded by the heavy rain, damaging nearby taro crops.[13] The rough seas also forced patrol boats in Honiara to be moved to prevent them from drifting offshore.[14] In the village of Tingoa, some locals took shelter in caves while other moved into emergency shelters.[11] It is estimated that about 2,000 people took shelter nationwide.[15] Disaster management officials sent relief supplies to Rennell and Bellona Islands, the islands that worst affected by the storm.[16]

Vanuatu, and New Caledonia

Vanuatu experienced strong winds from Beni, with gusts of up to 95 km/h (59 mph).[12] In the capital of Port Vila, structures near the coast were damaged by storm surge. Damage in the islands totaled to US$1 million.[nb 1][17] In Mele, the tide caused by Beni was only measured as high as 0.3 m (0.98 ft). Beach erosion occurred along the coasts of Vanuatu as well.[18]

Due to the impending approach of Beni, authorities in New Caledonia issued a low-level alert for the island.[15] In the Nouméa area, school holiday camps were closed and military personnel were sent to the Loyalty Islands in advance.[19] However, the alert for New Caledonia was lifted after Beni weakened and moved away from the islands.[20] Several power outages and structural damage occurred during the passing of Beni in the Loyalty Islands, which were caused by trees collapsing on power lines.[21] Rain peaked at 160 mm (6.3 in) in a mountain spring.[20]

Australia

Severe weather warnings were issued for Southeast Queensland between February 1 and 3 due to the impending conditions, and in Central Queensland, warnings were issued between the February 3 and 5.[9] Across the Sunshine Coast and Gold Coast, beaches were closed, and 12 people were rescued from outrigger canoes in Moreton Bay.[9] Supermarkets in the area stocked up extra supplies and equipment to prepare for Beni to better support evacuees and those sheltering.[22] Because of the threat of rough seas and high winds forced the delay of the New Zealand International Sprint Car Series that was to take place at the Western Springs Stadium, after a ship carrying the cars had to wait for the storm the pass.[23]

Although far from Australia at that time, storm cells from Beni produced gale–force winds would periodically form and affect areas of southeastern Queensland on February 2.[24] Strong winds caused a power outage in both Agnes Water and 1770 late on 5 February. Both cities were also isolated by floodwater.[9] In Wowan, many buildings were flooded by the heavy rains, and a total of 160 people were also cut off by floodwater.[9] Near Gladstone, many placed recorded rain totals in excess of 500 mm (20 in), although some of the rain was caused by a nearby upper-level low that was also over Queensland at the time.[12] Other areas of Western Queensland recorded rain totals of up to 200 mm (7.9 in), including in Augathella, Queensland, where rain peaked at 203 mm (8.0 in).[25] Runoff on the Fitzroy River caused by Cyclone Beni resulted in a moderate flood with an estimated return period of four years at Rockhampton.[26] The cyclone's heavy rains helped ease drought problems in Queensland. Nine shires in Central Queensland were declared disaster areas. At the Kroombit Dam, the water level increased from 0.5% to 81% due to Beni.[27] Water reserves were said to have replenished to five years' supply due to the storm.[28]

Flooding rains caused by Beni resulted in damages of at least A$10 million (US$6 million) in Queensland [nb 2] One person drowned due to the flooding rains.[24][29] Furthermore, the name Beni was retired after the season.[30]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 RSMC Nadi — Tropical Cyclone Centre (29 August 2007). Tropical Cyclone Seasonal Summary 2002-2003 season (PDF) (Report). Fiji Meteorological Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Padgett, Gary; Clarke, Simon; Waqaicelua, Alipate; Callaghan, Jeff (27 December 2006). Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary January, 2003 (Report). Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- 1 2 "2002 Tropical Cyclone Beni (2003021S10163)". International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Courtney, Joe B (2 June 2005). "The South Pacific and southeast Indian Ocean tropical cyclone season 2002–03" (PDF). Australian Meteorological Magazine. Australian Bureau of Meteorology. 54: 137–150. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- 1 2 Joint Typhoon Warning Center (24 January 2003). "Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert 24 January, 2003 21z". United States Navy, United States Air Force. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ↑ Joint Typhoon Warning Center (25 January 2003). "Tropical Cyclone 12P (Beni) Warning 1: 25 January 2003 03z". United States Navy, United States Air Force. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- 1 2 Joint Typhoon Warning Center. "Tropical Cyclone 12P (Beni) best track analysis". United States Navy, United States Air Force. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ↑ Darwin Regional Specialised Meteorological Centre (2003). "January 2003" (PDF). Darwin Tropical Diagnostic Statement. Australian: Bureau of Meteorology. 22 (1): 2. ISSN 1321-4233. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 February 2003 (Monthly Significant Weather Summary). Australian Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- 1 2 Pacific Islands Report (27 January 2003). "Solomons under cyclone seige once again". Pacific Islands Development Program/Center for Pacific Islands Studies. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- 1 2 Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (29 January 2003). "Solomon Islands — Cyclone Beni OCHA Situation Report No. 1". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- 1 2 3 Padgett, Garry; Clarke, Simon; Waqaicelua, Alipate; Callaghan, Jeff (27 December 2006). January, 2006. Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary (Report). Australian Severe Weather. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ↑ Australian Agency for International Development (29 January 2003). "Pacific Cyclones Update 29 Jan 2003". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ↑ Australian Broadcasting Corporation (27 January 2003). "Solomons: Another cyclone lashes islands". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- 1 2 ReliefWeb (29 January 2003). "New Caledonia braces for Cyclone Beni". Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ↑ Australian Broadcasting Corporation; Panichi, James (28 January 2003). "Solomons: Cyclone relief on the way to Rennel and Bellona". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ↑ "Catastrophe Insurance Pilot Project, Port Villa, Vanuatu: Developing Risk-Management Options for Disasters in the Pacific Region" (PDF). Secretariat of the Pacific Community Applied Geoscience and Technology Division. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ↑ Shorten, G.G.; Goosby, S.; Granger, K.; Lindsay, K.; Naidu, P.; Oliver, S.; Stewart, K.; Titov, V.; Walker, G. "Catastrophe Insurance Pilot Study, Port Vila, Vanuatu: Developing Risk-Management Options for Disasters in the Pacific Region, Volume 2" (PDF). Secretariat of the Pacific Community Applied Geoscience and Technology Division. pp. 110–114. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ↑ "Parts of New Caledonia on high alert as Cyclone Beni approaches". Radio New Zealand International. 29 January 2003. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- 1 2 Agence France-Presse (31 January 2003). Alert lifted in New Caledonia as tropical depression (Report). ReliefWeb. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ↑ De 1880 à nos jours (Report) (in French). Météo-France. Archived from the original on 20 September 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ↑ Australian Associated Press (4 January 2003). "Cyclone Beni threatens to hit Queensland". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ↑ "Cyclone stalls international sprintcar races". New Zealand Herald. 5 February 2003. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- 1 2 Courtney, J.B.; Australian Meteorological Magazine (April 2005). "The South Pacific and southeast Indian Ocean tropical cyclone season 2002-03" (PDF). Perth: Bureau of Meteorology. pp. 145–146. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ↑ ABC Rural Broadcasting News (10 February 2003). "Ex-cyclone Beni delivers up to 200mm rain to Western QLD". Australian Broadcasting Company. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ↑ Robert, Packett; National Action Plan for Salinity and Water Quality; Queensland Department of Natural Resources and Water. "A mouthful of mud: the fate of contaminants from the Fitzroy River, Queensland, Australia and implications for reef water policy" (PDF). Charles Sturt University. pp. 296–297. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ↑ "Drought one day, then flood in Qld". The Age. Australian Associated Press. 7 February 2003. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ↑ Corder, G.D.; Moran, C.J. (2006). "The Importance of Water in the Gladstone Industrial Area" (PDF). University of Queensland. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 April 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ↑ "Beni flood costs $10m". The Age. Australian Associated Press. 7 February 2003. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ↑ RA V Tropical Cyclone Committee (2023). Tropical Cyclone Operational Plan for the South-East Indian Ocean and the Southern Pacific Ocean 2023 (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

Notes

- ↑ All damage totals are in their respective currency values in 2003

- ↑ In order to convert the value of 10 million AUD, the values of the currencies were taken from their respective values on 5 February 2003. For the value of 1 million USD, the values of the currencies were taken from their respective values on 30 January 2003.

External links

- World Meteorological Organization

- Australian Bureau of Meteorology

- Fiji Meteorological Service

- New Zealand MetService

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center