| The Battle of Gettysburg (detail) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Paul Philippoteaux |

| Year | 1883 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 13 m × 115 m (42 ft × 377 ft) |

| Location | Museum and Visitor Center, Gettysburg National Military Park, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania |

The Battle of Gettysburg, also known as the Gettysburg Cyclorama, is a cyclorama painting by the French artist Paul Philippoteaux depicting Pickett's Charge, the climactic Confederate attack on the Union forces during the Battle of Gettysburg on July 3, 1863.[1]

Description

The painting is the work of French artist Paul Dominique Philippoteaux. It depicts Pickett's Charge, the failed infantry assault that was the climax of the Battle of Gettysburg. The painting is a cyclorama, a type of 360° cylindrical painting. The intended effect is to immerse the viewer in the scene being depicted, often with the addition of foreground models and life-sized replicas to enhance the illusion. Among the sites documented in the painting are Cemetery Ridge, the Angle, and the "High-water mark of the Confederacy".[1] The completed original painting was 22 feet (6.7 m) high and 279 feet (85 m) in circumference.[2] The version that hangs in Gettysburg, a recent (2005) restoration of the version created for Boston, is 42 feet (13 m) high and 377 feet (115 m) in circumference.[1]

Details of the painting:

Pickett's Charge up Cemetery Ridge.

Pickett's Charge up Cemetery Ridge._Cyclorama_2012.jpg.webp) Confederate General Lewis Armistead at The Angle (an artist's mistake, as Armistead was not on horseback and ran the last yards with his sword over his head holding his hat on its tip. He was shot three times, and died, probably of sepsis, two days later in a Union field hospital).

Confederate General Lewis Armistead at The Angle (an artist's mistake, as Armistead was not on horseback and ran the last yards with his sword over his head holding his hat on its tip. He was shot three times, and died, probably of sepsis, two days later in a Union field hospital).

Caisson exploding

Caisson exploding_Cyclorama_2012.jpg.webp) General George Meade and staff advancing toward Cemetery Ridge

General George Meade and staff advancing toward Cemetery Ridge_Cyclorama_2012.jpg.webp) General Winfield Scott Hancock

General Winfield Scott Hancock_Cyclorama_2012.jpg.webp) Union infantry and artillery advancing Toward The Angle

Union infantry and artillery advancing Toward The Angle_Cyclorama_2012.jpg.webp) Union Line on Cemetery Ridge

Union Line on Cemetery Ridge_Alonzo_Cushing_at_The_Angle_July_3%252C_1863_--_Gettysburg_(PA)_Cyclorama_2012.jpg.webp) Union Major Alonzo Cushing at The Angle

Union Major Alonzo Cushing at The Angle

Development

Philippoteaux became interested in cycloramas and, in collaboration with his father, created The Defence of the Fort d'Issy in 1871. Other successful works included Taking of Plevna (Turko-Russian War), the Passage of the Balkans, The Belgian Revolution of 1830, Attack in the Park, The Battle of Kars, The Battle of Tel-el-Kebir, and the Derniere Sortie.[5] He was commissioned by a group of Chicago investors in 1879 to create the Gettysburg Cyclorama. He spent several weeks in April 1882 at the site of the Gettysburg Battlefield to sketch and photograph the scene, and extensively researched the battle and its events over several months. He erected a wooden platform along present-day Hancock Avenue and drew a circle around it, eighty feet in diameter, driving stakes into the ground to divide it into ten sections. Local photographer William H. Tipton took three photographs of each section, focusing in turn on the foreground, the land behind it, and the horizon. The photos, pasted together, formed the basis of the composition.[6] Philippoteaux also interviewed several survivors of the battle, including Union generals Winfield S. Hancock, Abner Doubleday, Oliver O. Howard, and Alexander S. Webb, and based his work partly on their recollections.[5]

Philippoteaux enlisted a team of five assistants, including his father until his death, to create the final work.[5] It took over a year and a half to complete.[1] The finished painting was nearly 100 yards long and weighed six tons.[2] When completed for display, the full work included not just the painting, but numerous artifacts and sculptures, including stone walls, trees, and fences.[1] The effect of the painting has been likened to the nineteenth century equivalent of an IMAX theater.[2]

Chicago version

In 1879, the National Panorama Company, led by Charles Louis Willoughby and supported by Marshall Field, Judge Treat, Jefferson Printing Company and an assortment of other capitalists commissioned the artist Paul Dominique Philippoteaux to begin works on a cyclorama of the Battle of Gettysburg. Preparation began in 1880 and by 1883 the National Panorama Company had taken possession of the monumental cyclorama painting which became known as the Gettysburg Cyclorama, Chicago version (so-named for the city in which it was first exhibited).

The work opened to the public in Chicago on October 22, 1883, to critical acclaim.[5] General John Gibbon, one of the commanders of the Union forces who repelled Pickett's Charge, was among the veterans of the battle who gave it favorable reviews.[1] So realistic was the painting that many veterans of the war were reported to have wept upon seeing it.[7]

| Year | Location |

|---|---|

| 1883 | Panorama Building, Hubbard Court, Chicago, Illinois |

| 1893 | World's Fair, Chicago, Illinois |

Wake Forest University/ Joe King Version (hereinafter WFU version) It was originally believed that Joe King, a Winston-Salem artist tracked down this Chicago version and later donated it to Wake Forest University, where it was then sold to three NC investors before it was donated in 6/2019 to the Civil War and Reconstruction History Center.

However, The authors of Gettysburg Cyclorama, The Turning Point of the Civil War on Canvas, Boardman and Brenneman present extensive historical research that concludes that the WFU version is not one of the original four done directly under Philippoteaux's direction, but is rather one done under the direction of Austen, using Philippoteaux's drawings, and with many artists from Philippoteaux's studio. Furthermore, they cite newspaper articles showing that what they believe to be the Chicago version was destroyed in a storm in Omaha in 1894, and they also present evidence that Austen directed the production of the WFU cyclorama in 1905. This WFU version was recently featured on WRAL's Tarheel Traveler program.[8]

Boston version

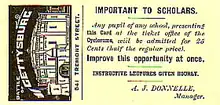

The Chicago exhibition was sufficiently successful to prompt businessman Charles L. Willoughby to commission a second version, which opened in Boston, Massachusetts, on December 22, 1884. From its opening until 1892, approximately 200,000 people viewed the painting.[5] The Boston version was housed in a specially designed building, the Cyclorama Building, on Tremont Street,[9] and was the site of popular public lectures on the battle.[1] Two additional copies of the cyclorama were made: the third was first exhibited in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, beginning in February 1886 and a fourth debuted in Brooklyn, New York, in October 1886.[5]

Many reviewers and visitors agreed with the Boston Daily Advertiser that "it is impossible to tell where reality ends and the painting begins." One veteran, pointing at the painting, said to his friend: "You see that puff of smoke? Just wait a moment till that clears away, and I'll show you just where I stood." In New York, police responding to a report of a nighttime burglary and disoriented by the illusion twice seized dummies representing dead soldiers, convinced that they were live burglars.[6][7]

In 1891, the Boston cyclorama, housed in the Cyclorama Building, was exchanged temporarily with the cyclorama Crucifixion of Christ, also one of Philippoteaux's works[10] When it returned in 1892, it was stored in a 50-foot (15 m) crate behind the exhibition hall, where it was subjected to damage from weather, vandals removing boards from the crate, and two fires. It was eventually purchased in its deteriorated state by Albert J. Hahne of Newark, New Jersey, in 1910. Hahne displayed sections of the cyclorama in his department store in Newark beginning in 1911, and sections were also shown in government buildings in New York City, Baltimore, Maryland, and Washington, D.C. In the Baltimore exhibition, George E. Pickett's widow, "Sallie" Pickett, lectured on her husband's experiences and found herself very moved by the experience.[5]

In 1894, Chase & Everhart displayed their Cyclorama of the Battle of Gettysburg during a National Guard encampment at Gettysburg.[11]

On September 3, 1912, ground was broken for a new cyclorama building on Baltimore Street in Gettysburg, on Cemetery Hill (on the site of the present day Holiday Inn), near the entrance to the Soldiers' National Cemetery. It opened to the public in 1913, in time for the 50th anniversary of the battle, once again displayed as a full circular painting, rather than in sections. The unheated, leaky brick building took a further toll on the condition of the painting. The Boston cyclorama was purchased by the National Park Service in 1942, and moved to a site on Ziegler's Grove near the new Visitor's Center in 1961, after a second round of restoration.[5]

The exhibition remained open to the public until 2005, when it was closed for a third restoration.[1] The $12-million restoration, by Olin Conservation, Inc., of Great Falls, Virginia, started with the 26 sections of the painting and recreated its original shape of 14 panels hung from a circular railing, slightly flared out at the bottom. In the process, some original pieces were found of the 12 circumferential feet that had been cut away. Fourteen vertical feet of sky was also restored.[9]

The painting restoration was accompanied by the construction of a facility to house the painting, the new Gettysburg Museum and Visitor Center on Hunt Avenue, located away from any areas in which fighting occurred in 1863. The restored Cyclorama exhibition was reopened to the public in September 2008. The proposed demolition of the old Cyclorama building in Ziegler's Grove was a source of some controversy among history and architecture buffs, with some opposing the destruction of the modernist structure designed by architect Richard Neutra.[14] Nevertheless, it was razed in early 2013, and the site restored to its wartime appearance.[15]

The Benedict "Buck-eye"

A buck-eye cyclorama is a cyclorama painting of the same or roughly the same dimensions as an original, which is a very slavish copy. These were often created cheaply by painters of little skill and almost always with sub-standard materials. Several buck-eye cycloramas were exhibited in the United States during the time when cyclorama paintings were popular attractions, including several copies of the Gettysburg Cyclorama. Once an individual had seen a particular cyclorama, it was unlikely that they would purchase a ticket to revisit it. This meant that the low-quality copies could be exhibited with a very low risk that a ticket holder would request a refund, as they would likely never have seen the original. Tickets could be sold at the same price as the admission to see an original and the exhibitor of a buck-eye could visit the original themselves, obtain copies of all of the pamphlets and promotional materials, and have them cheaply copied for sale alongside the attraction. In fact, copy houses were formed in order to meet the demand for such paintings, one being the Milwaukee Panorama Painters.

In 1885 the Milwaukee Panorama Painters were commissioned by Mr. Myron Herrick (at that time a banker, who later twice served as the U.S. Ambassador to France) to create a copy of the Gettysburg Cyclorama, which was later purchased by E. W. McConnell (the "Cyclorama King") and exhibited by McConnell at: the Cotton States Exposition, Atlanta, Georgia in 1895; the Tennessee Centennial Exposition, Nashville, Tennessee in 1897; before moving to Louisville, Kentucky; and finally, to Nashville, Tennessee in 1898 before it was placed in storage in that city. During the time of McConnell's ownership, McConnell sold a share of the painting to a Mr. Benedict who, in turn, sold a share of his share to a Mr. Graves.

In 1920, more than 20 years after the buck-eye had been placed into storage, Benedict informed McConnell that a flood had ruined the buck-eye painting, but failed to inform Graves. Graves was not available to be consulted when questions from his family arose regarding the whereabouts of the buck-eye (in 1957) and the beneficiaries of Graves' Estate later made the assumption that the painting purchased by Mr. Joseph Wallace King (the Chicago Version) in 1964 was this 'missing' buck-eye painting. The estate then launched a legal action against King, claiming that a share of the painting King had purchased was theirs. This case was settled in arbitration by the comparison of photographs of the buck-eye with the painting King had purchased and the matters were resolved in King's favour, as the buck-eye was obviously of inferior quality to the Chicago Version which King had in his possession.

In 1957 the Milwaukee County Historical Society contacted the firm of lawyers who had been acting for McConnell and asked if they could purchase the painting and were informed that it had been destroyed.

See also

Notes and references

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Heiser, John. "The Gettysburg Cyclorama". Gettysburg National Military Park. National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 Jarvis, Craig (May 2, 2007). "Triangle trio buys massive painting". The News & Observer (Raleigh, NC). The News and Observer Publishing Company. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-03.

- ↑ Kalina-Metzger, Stephanie (April 24, 2014). "Gettysburg event takes residents back in time with cyclorama". The Sentinel Newspaper. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ↑ Chris Brenneman; Sue Boardman (19 May 2015). The Gettysburg Cyclorama: The Turning Point of the Civil War on Canvas. Savas Beatie. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-61121-264-8. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Thomas, Dean S. (1989). The Gettysburg Cyclorama: A Portrayal of the High Tide of the Confederacy. Gettysburg, Pennsylvania: Thomas Publications. pp. 17–19. ISBN 0-939631-14-8.

- 1 2 Appelbaum, Yoni (8 February 2012). "The Half-Life of Illusion: On the Brief and Glorious Heyday of the Cyclorama". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- 1 2 Appelbaum, Yoni (5 February 2012). "The Great Illusion of Gettysburg". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ↑ "[Homepage]". Heirloom Estates. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- 1 2 Morton, Margaret (July 2007). "Work in Progress". Civil War Times. pp. 28–35.

- ↑ Also one of Philippoteaux's works, Crucifixion is now on display at Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré, Quebec

- ↑ "Cyclorama" (Google News Archive). Gettysburg Compiler. July 31, 1894. p. 2 col. 3. Retrieved 2011-01-23.

- ↑ Worden, Amy (March 12, 2013). "Gettysburg's Cyclorama building is no more". Philadelphia Inquirer.

- ↑ Stansbury, Amy (9 March 2013). "The death of the Gettysburg Cyclorama building". The Evening Sun. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ "The Latest: Recent Past Preservation Network Sues National Park Service to Prevent Demolition of Historic Building at Gettysburg". CYCLORAMA: Richard Neutra's 1961 Lincoln Memorial at Gettysburg. Mission66.com. Archived from the original on 2013-01-29. Retrieved 2007-05-08.

- ↑ Burnett, Jim (4 April 2013). "Gettysburg National Military Park's Old Cyclorama Building Is No More". National Parks Traveler.