.jpg.webp)

During the American Civil War, Philadelphia was an important source of troops, money, weapons, medical care, and supplies for the Union.

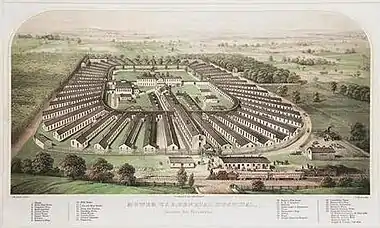

Before the Civil War, Philadelphia's economic connections with the South made much of the city sympathetic to South's grievances with the North. Once the war began, many Philadelphians' opinion shifted in support for the Union and the war against the Confederate States. More than 50 infantry and cavalry regiments were recruited fully or partly in Philadelphia. The city, the main source for uniforms for the Union Army, also manufactured weapons and built warships. Philadelphia also had the two largest military hospitals in the United States: Satterlee Hospital and Mower Hospital.

In 1863, Philadelphia was threatened by Confederate invasion during the Gettysburg Campaign. Entrenchments were built to defend the city, but the Confederate Army was turned back at Wrightsville, Pennsylvania, and at the Battle of Gettysburg. The Civil War's main legacy in Philadelphia was the rise of the Republican Party. Despised before the war because of its anti-slavery position, the party created a political machine that would dominate Philadelphia politics for almost a century.

Prewar

Antebellum Philadelphia was the second-largest city in the United States. Its strong economic ties with to the South fostered political sympathy; for example, political leaders in the city called for the repeal of laws that might be considered unfriendly to South. Meetings led to calls for Pennsylvania to decide which side the state was on in the case of Southern secession. Many blamed the Abolitionist movement for the crisis, and Abolitionists in the city were harassed and threatened.[1]

In the 1860 mayoral election, the Democratic Party candidate John Robbins challenged the People's Party candidate and incumbent mayor, Alexander Henry.[2] The People's Party in Pennsylvania was aligned with the national Republican Party but downplayed the issue of slavery and made tariff protection its main issue in the state. During the election, the Democrat attacked Henry's moderate position on slavery as virtual Abolitionism. He was reelected, but vote tampering was alleged. In the election for governor, Philadelphia gave the Democrats 51 percent of the vote, and in the presidential election, the Republicans' Abraham Lincoln won 52 percent of the city's vote.[1]

After the election, Philadelphia City Council voted to invite Lincoln to speak in the city with only one dissenting vote. He accepted and spoke twice, once at the Continental Hotel and once at the Pennsylvania State House. His speech marked a turning point in attitude for much of the Philadelphia elite.[3]

Civil War

After the American Civil War officially began with the attack on Fort Sumter in South Carolina, popular opinion in Philadelphia shifted. American flags and bunting appeared all over the city as Philadelphians moved their anger from Abolitionists to southern sympathizers. A mob threatened the home of the Palmetto Flag, a secessionist newspaper. The police and Mayor Henry were able to prevent the mob from causing damage, but the newspaper shut down shortly afterward. Other newspapers that had a pro-southern slant also suffered from a dwindling circulation.[4] When The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that the Union lost the First Battle of Bull Run, which contradicted initial government reports, a mob threatened to burn down its office.[5] Another personal appearance by Mayor Henry prevented a riot at the home of the prominent Democrat and grandson of Joseph Reed, William B. Reed. Other people with suspected pro-southern ties displayed American flags to avoid trouble.[4]

The initial enthusiasm at the beginning of the war soon diminished, but critics were still targeted. Around August 1861, federal authorities arrested eight people for expressing Confederate sympathies. Most of the people were released soon afterward, but one, the son of William H. Winder, was held for more than a year. Authorities also shut down a pro-southern weekly newspaper, the Christian Observer.[6] In 1862, after expressing antiwar sentiments, former Democratic Representative Charles Jared Ingersoll was arrested for discouraging enlistments. The arrest of the well-respected politician caused local Republicans embarrassment, and he was released after direct orders from the federal government.[7]

The city's Democrats used Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus and his Emancipation Proclamation as ammunition against Republicans. However, many in Philadelphia agreed with The Philadelphia Inquirer, which claimed in a July 1862 article that "in this war there can be but two parties, patriots and traitors."[7] Democrats did poorly in the 1862 election with Democratic Representative Charles John Biddle losing to Charles O'Neill, leaving only one Democrat from Philadelphia in the US House of Representatives. Samuel J. Randall, the only Democrat from Philadelphia in the House, was closer to Republicans than his own party.[8] Henry, running on the National Union Party ticket, was elected to a third term as Philadelphia mayor.[7]

Invasion threat

In June 1863, General Robert E. Lee invaded Pennsylvania in the Gettysburg Campaign. As word reached Philadelphia that the Confederate Army was marching on Harrisburg some 100 miles to the west, Philadelphians felt no urgency to prepare the city to defend itself. On June 26, Major-General Napoleon Jackson Tecumseh Dana took command of the military district of Philadelphia and began to build defensive entrenchments, with the help of volunteers recruited by Mayor Henry. At the beginning of July, Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Gregg Curtin came to the city in the hope to rally the city out of its lack of urgency.[9]

Philadelphia's Twentieth Pennsylvania Emergency Regiment and its First City Troop were among the militia that helped prevent the Confederate forces from crossing the Susquehanna River at Wrightsville by burning the Columbia-Wrightsville Bridge. The threat of invasion ended on July 3, when Lee's Army of Northern Virginia was defeated by the Army of the Potomac, commanded by George Meade, in the three-day Battle of Gettysburg.[9]

After Gettysburg

After the Gettysburg Campaign, support for the war grew, and hopes for antiwar elements to make headway in the city diminished. After the victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, patriotic feelings grew, more people enlisted in the army, and Philadelphia voted for the re-election of Republican Governor Curtin over the Peace Democrat George Washington Woodward. In July 1863 the draft began to be enforced in the city. Mayor Henry and General George Cadwalader, who replaced Major-General Dana as the commander of Philadelphia military district, quietly suppressed any disturbances to prevent riots similar to the draft riots in New York City.[10]

In June 1864, the Philadelphia division of the United States Sanitary Commission organized a large fair to raise money to buy bandages and medicine. The Great Central Fair lasted two weeks and was held in temporary buildings covering several acres of Logan Square. Thousands of works of art were lent for display, and many were donated for auction. Among the visitors was Lincoln.[10] The Sanitary Fair raised $1,046,859.[11]

In the 1864 election, most Philadelphians voted to re-elect Lincoln and the four representatives from Philadelphia. The National Union Party also gained majority in both houses of the Philadelphia City Council.[8]

In December 1864, Philadelphia's streetcar companies began either allowing African Americans on the streetcars or running streetcars specifically for African Americans. The companies capitulated after African Americans and others put pressure on the companies because African American soldiers were reporting late for duty and soldiers' wives experienced trouble visiting their wounded husbands in the hospitals. The city's streetcars were not fully integrated until 1867, when they were required by a law passed by the Pennsylvania General Assembly.[12]

Military contribution

Many soldiers from New England and New Jersey came through Philadelphia while they were heading south.[13] Many soldiers moved through New Jersey via the Camden and Amboy Railroad and then the Delaware River by ferry. The ferry would drop them off at Washington Avenue, where they would march to waiting trains of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad. Local residents formed two organizations, the Union Volunteer Refreshment Saloon and the Cooper Shop Refreshment Saloon, to greet the arriving soldiers with refreshments and letter-writing materials.[14]

The first Philadelphia regiment sent out of the city was a volunteer formation, the Washington Grays, which was dispatched to help defend Washington, DC. The unit made it to Baltimore, Maryland, where it was attacked by a secessionist mob in the Baltimore riot of 1861. The brigade retreated to Philadelphia, where George Leisenring, a German-born private, died and became Philadelphia's first war casualty.

The first Philadelphians to encounter Confederate forces were the Twenty-third Infantry Regiment and the First City Troop at the Battle of Hoke's Run in West Virginia. More than 50 infantry and cavalry regiments were eventually recruited fully or partly in Philadelphia.[13] They included the Philadelphia Brigade and the 118th Pennsylvania Infantry, recruited and sponsored by the Philadelphia Corn Exchange.[15] In addition, 11 United States Colored Troops were organized in Philadelphia. During the war, between 89,000 and 90,000 Philadelphians were on enlistment rolls. The number includes re-enlistments but not African American soldiers from Philadelphia, whose enlistment numbers are unknown.[13]

Philadelphia's Schuylkill Arsenal was the US Army's main source for uniforms. Hundreds of workers in Philadelphia made parts of the uniforms in their homes to be assembled at the arsenal.[13] The Frankford Arsenal manufactured munitions and the Sharp and Rankin's factory-made breech-loading rifles. The Philadelphia Navy Yard, employing 3,000 people, built 11 warships and outfitted many more. Philadelphia's private shipyards, including William Cramp & Sons, also constructed many ships, such as the USS New Ironsides.[14]

Over the course of the war, Philadelphia was the site of 24 military hospitals. Philadelphia had as many as 10,000 beds for soldiers, not including the beds in the 22 civilian hospitals, which sometimes cared for soldiers. The Union Refreshment Saloon created the first military hospital in the city. Its hospital had 15 beds for sick soldiers passing through the city. Smaller hospitals, such as the Haddington Hospital and the Citizens' Volunteer Hospital both with 400 beds, were among the earliest to be set up. They were eventually closed to allow more focus on Philadelphia's largest military hospitals. The hospitals, the largest military hospitals in the United States, were Satterlee Hospital with 3,124 beds and Mower Hospital with 4,000 beds. In total, around 157,000 soldiers and sailors were treated in Philadelphia hospitals.[14][16]

Legacy

The Civil War led to decades of dominance by the Republican Party in the city's politics. Antebellum Republicans had held little support in the city, mainly because of the party's anti-slavery position. However, the Democrats' opposition to the war transferred so much popular support to Republicans during and after the war that it allowed the creation of a powerful and eventually-corrupt political machine, which would dominate city politics for almost a century.[8][17]

In 1861, a group of prominent Philadelphians founded the Union Club in response to pro-southern support in another social club, the Wistar Club. The Union Club became the Union League in 1863 and abolished its membership limit of 50. With 1,000 members by the end of the war, the Union League became a center of Republican politics and still exists as one of Philadelphia's largest and most prestigious social clubs.[18][19]

The Civil War also helped create some of Philadelphia's upper class. The Philadelphia banker Jay Cooke made a fortune selling Union war bonds worth roughly $1 billion. The future streetcar magnate Peter Widener amassed his initial wealth by supplying meat to the Union Army; John and James Dobson made their fortune manufacturing blankets.[20]

Memorials

.jpg.webp)

The Civil War Library and Museum, now the Civil War Museum of Philadelphia, was founded in 1888. The oldest chartered American Civil War institution, the Civil War and Underground Railroad Museum of Philadelphia, was founded by the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States; it collects records, artifacts, and other items related to the Civil War and the Underground Railroad .[21]

On the Benjamin Franklin Parkway is the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Memorial. Designed by Hermon Atkins MacNeil and completed in 1927, the memorial comprises two 40 ft (12 m) pylons sitting on each side of the parkway.[22][23]

Across 20th Street, is the All Wars Memorial to Colored Soldiers and Sailors (1934) by J. Otto Schweizer. Originally erected in West Fairmount Park, it was moved to Logan Circle in 1994.[24]

Philadelphia's largest Civil War monument is the Smith Memorial Arch, built on the former grounds of the 1876 Centennial Exposition in West Fairmount Park. Designed by James H. Windrim, and completed in 1912, it includes sculptures by Herbert Adams, George Bissell, Alexander Stirling Calder, Daniel Chester French, Charles Grafly, Samuel Murray, Edward Clark Potter, John Massey Rhind, Bessie Potter Vonnoh, and John Quincy Adams Ward.[25]

Notable people from Philadelphia

The Philadelphia area was the birthplace or long-time residence of several Union army generals and naval admirals. The city's most celebrated war hero was Major General George G. Meade (1815-1872), whose fame in the city came from his success at the Battle of Gettysburg and as commander of the Army of the Potomac.[9][20] Philadelphia celebrated returning war heroes and Civil War veterans with parades. On June 10, 1865, the city held a grand review, with Meade leading veteran soldiers through the city in to a dinner at a volunteer refreshment saloon. Another grand review of Civil War veterans was held as part of the Independence Day celebration in 1866. The parade was led by another Philadelphian war hero, Winfield Scott Hancock (1824–1886).[26]

Others generals from Philadelphia included the filloy:

- George B. McClellan (1826–1885)

- Andrew A. Humphreys (1810–1883)

- David B. Birney (1825–1864)

- John Gibbon (1827–1896)

- George A. McCall (1802–1868)

- George Cadwalader (1806–1879)[10]

- Joseph Barnes (1817–1883)

- Robert Patterson (1792–1881)

- Charles F. Smith (1807–1862)

- Thomas L. Kane (1822–1883)

Fifty-four soldiers and sailors from Philadelphia received the Medal of Honor. Among them were Sergeant Richard Binder, Captain Henry H. Bingham, Captain John Gregory Bourke, Captain Cecil Clay, Private Richard Conner, Quartermaster Thomas Cripps, Captain Frank Furness, Sailor Richard Hamilton, Coal Heaver William Jackson Palmer, Captain Forrester L. Taylor, and Fireman Joseph E. Vantine.[27]

References

- 1 2 Weigley RF et al (eds) (1982). Philadelphia: A 300-Year History. New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 391–393. ISBN 0-393-01610-2.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ↑ "Mayors of the City of Philadelphia". The Philadelphia Information Locator System. City of Philadelphia. 1998-01-13. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ↑ Philadelphia: a 300 year history. Weigley, Russell Frank., Wainwright, Nicholas B., Wolf, Edwin, 1911-1991. (1st ed.). New York: W.W. Norton. 1982. ISBN 0393016102. OCLC 8532897.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - 1 2 Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, pp. 384, 394

- ↑ Williams, Edgar (June 20, 2003). "A history of The Inquirer". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on 2007-02-19. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ↑ Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, p. 403

- 1 2 3 Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, p. 405

- 1 2 3 Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, p. 413

- 1 2 3 Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, pp. 408–410

- 1 2 3 Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, pp. 411–412

- ↑ Frank H. Taylor, Philadelphia in the Civil War (Philadelphia: Dunlap Printing Co., 1913), p. 264.

- ↑ Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, pp. 415–416

- 1 2 3 4 Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, pp. 395–396

- 1 2 3 Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, pp. 398–399

- ↑ Gayley, Alice J. "118th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers". Pennsylvania in the Civil War. Alice J. Gayley. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- ↑ Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, page 402

- ↑ Avery, Ron (1999). A Concise History of Philadelphia. Philadelphia: Otis Books. pp. 66–68. ISBN 0-9658825-1-9.

- ↑ Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, p. 407

- ↑ A Concise History of Philadelphia, p. 60

- 1 2 A Concise History of Philadelphia, page 61

- ↑ "About Us". The Civil War and Underground Railroad Museum of Philadelphia. Archived from the original on 2008-07-25. Retrieved 2008-08-14.

- ↑ Brookes, Karin; John Gattuso; Lou Harry; Edward Jardim; Donald Kraybill; Susan Lewis; Dave Nelson; Carol Turkington (2005). Zoë Ross (ed.). Insight Guides: Philadelphia and Surroundings (Second Edition (Updated) ed.). APA Publications. p. 178. ISBN 1585730262.

- ↑ "Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Memorial". www.gophila.com. Greater Philadelphia Tourism Marketing Corporation. Retrieved 2008-08-14.

- ↑ All Wars Memorial

- ↑ Smith Memorial Arch from Philadelphia Public Art.

- ↑ Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, p. 418

- ↑ "PA Civil War Medal of Honor Recipients". Pennsylvania Civil War Volunteers. Retrieved 2008-08-16.

Further reading

- Dusinberre, William. Civil War Issues in Philadelphia, 1856–1865 (Philadelphia, 1965), the main scholarly study

- Neely Jr, Mark E. "Civil War Issues in Pennsylvania: A Review Essay." Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 135.4 (2011): 389–417. online

- Sauers, Richard A. Guide to Civil War Philadelphia (Da Capo Press, 2003).

- Taylor, Frank H. Philadelphia in the Civil War, 1861-1865 (1913) online

- Tremel, Andrew T. "The Union League, Black Leaders, and the Recruitment of Philadelphia's African American Civil War Regiments." Pennsylvania History 80.1 (2013): 13–36. in JSTOR