| Czech Philharmonic | |

|---|---|

| Orchestra | |

| Native name | Česká filharmonie |

| Founded | 1896 |

| Location | Prague |

| Concert hall | Rudolfinum |

| Principal conductor | Semyon Bychkov |

| Website | ceskafilharmonie |

The Czech Philharmonic (Czech: Česká filharmonie) is a symphony orchestra based in Prague.[1] It belongs to the oldest and most important world orchestras and is appreciated for its specific warm tone. The main stage of the orchestra is the Rudolfinum concert hall.

History

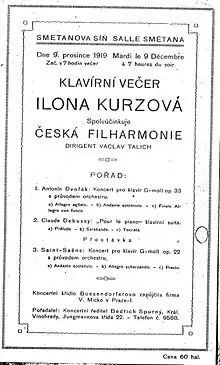

The name "Czech Philharmonic Orchestra" appeared for the first time in 1894, as the title of the orchestra of the Prague National Theatre.[1] It played its first concert under its current name on January 4, 1896 when Antonín Dvořák conducted his own compositions, but it did not become fully independent from the opera until 1901. The first representative concert took place on October 15, 1901 conducted by Ludvík Čelanský, the first artistic director of the orchestra.[1] In 1908, Gustav Mahler led the orchestra in the world premiere of his Symphony No. 7. The orchestra first became internationally known during the principal conductorship of Václav Talich, who held the post from 1919 to 1931, and again from 1933 to 1941. In 1941, Talich and the orchestra made a controversial journey to Germany, where they performed Bedřich Smetana's My Country in a concert enforced by the German offices.[1]

Subsequent chief conductors included Rafael Kubelík (1942–1948), Karel Ančerl (1950–1968), Václav Neumann (1968–1989), Jiří Bělohlávek (1990–1992), Gerd Albrecht (1993–1996), Vladimir Ashkenazy (1996–2003), Zdeněk Mácal (2003–2007),[2] and Eliahu Inbal (2009–2012). In the wake of the Velvet Revolution, under new conditions of financial insecurity, the orchestra reorganised in 1991 and controversially voted to appoint Gerd Albrecht its new chief conductor and to dismiss Bělohlávek. Instead of remaining until Albrecht's accession, Bělohlávek resigned from the orchestra in 1992.[3] In December 2010, the orchestra announced the reappointment of Bělohlávek as chief conductor, beginning in 2012,[4] with an initial contract of 4 years.[5] The orchestra's official English name changed from the "Czech Philharmonic Orchestra" to the "Czech Philharmonic" at the beginning of 2015. In January 2017, the orchestra announced the extension of Bělohlávek's contract through the 2021–2022 season.[6] Bělohlávek continued to serve as the orchestra's chief conductor until his death on 31 May 2017.[7]

In 2013, Semyon Bychkov first guest-conducted the orchestra, which subsequently named him director of its Tchaikovsky Project. In October 2017, the orchestra announced the appointment of Bychkov as its next chief conductor and music director, effective with the 2018–2019 season.[8] In September 2022, the orchestra announced the extension of Bychkov's contract through 2028.[9]

Past principal guest conductors of the orchestra have included Sir Charles Mackerras and Manfred Honeck. Jakub Hrůša is the orchestra's current 'permanent guest conductor', as of the 2015–2016 season. In October 2017, the orchestra announced the appointments of Hrůša and of Tomáš Netopil as joint principal guest conductors of the orchestra, effective with the 2018–2019 season.[8]

The Czech Philharmonic's first phonograph recording dates from 1929, when Václav Talich recorded My Country for His Master's Voice. The orchestra recordings are most often released on the Supraphon label.

Honours and awards

The Czech Philharmonic has won many awards, ten Grand Prix du Disque de l'Académie Charles Cros, five Grand Prix du disque de l'Académie française and several Cannes Classical Awards. The Czech Philharmonic was nominated for Grammy Awards in 2005, and also two Wiener Flötenuhr awards, with Pavel Štěpán, Zdeněk Mácal and Václav Neumann (1971 and 1982).[10] It was voted 20th place of the top 20 best orchestras in the world in a 2008 survey by Gramophone magazine.[11]

Chief conductors

- Ludvík Čelanský (1901–1903)

- Vilém Zemánek (1903–1918)

- Václav Talich (1919–1931, 1933–1941)

- Rafael Kubelík (1942–1948)

- Karel Šejna (1950)

- Karel Ančerl (1950–1968)

- Václav Neumann (1968–1989)

- Jiří Bělohlávek (1990–1992)

- Gerd Albrecht (1993–1996)

- Vladimir Ashkenazy (1996–2003)

- Zdeněk Mácal (2003–2007)

- Eliahu Inbal (2009–2012)

- Jiří Bělohlávek (2012–2017)

- Semyon Bychkov (2018–present)

References

- 1 2 3 4 Černušák, Gracián; Štědroň, Bohumír; Nováček, Zdenko, eds. (1963). Československý hudební slovník (in Czech). Vol. I. A–L. Prague: Státní hudební vydavatelství. p. 203.

- ↑ Matthew Westphal (2007-09-11). "Angry Over Bad Review, Conductor Zdenek Mácal Abruptly Quits Czech Philharmonic". Playbill Arts. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ↑ John Rockwell (1992-12-30). "Czech Philharmonic Faces Perilous Times in Dividing Country". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-03-24.

- ↑ "Šéfdirigentem České filharmonie bude Jiří Bělohlávek". ČTK (in Czech). ČeskéNoviny.cz. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ↑ "Bělohlávek to become Czech Philharmonic's chief conductor in 2012". Prague Daily Monitor. 2010-12-23. Retrieved 2012-03-24.

- ↑ Daniel Konrád (2017-01-01). "Šéfdirigent Bělohlávek prodloužil smlouvu, Českou filharmonii povede do roku 2022". Hospodářské Noviny. Retrieved 2017-01-05.

- ↑ David Nice (2017-06-01). "Jiří Bělohlávek obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 2017-06-02.

- 1 2 Martin Cullingford (2017-10-16). "Semyon Bychkov to take top job at Czech Philharmonic". Gramophone. Retrieved 2017-10-17.

- ↑ "Šéfdirigent Semjon Byčkov prodlužuje smlouvu s Českou filharmonií" (Press release). Czech Philharmonic. 28 September 2022. Retrieved 2022-09-30.

- ↑ "Mozart: Koncerty pro klavír a orchestr (Pavel Štěpán, Česká filharmonie, Zdeněk Mácal)", Supraphonline

- ↑ "The world's greatest orchestras". Gramophone. London. 2008.

Further reading

- Václav Holzknecht. Česká filharmonie. Příběh orchestru (in Czech). Prague: SHN.

- Karel Mlejnek (1996). Česká filharmonie (in Czech). Prague: Paseka.

- Vladimír Šefl (1971). Česká filharmonie (in Czech). Prague: Czech Philharmonic.

- Sláma, František (2001). Z Herálce do Šangrilá a zase nazpátek [From Heralec to Shangrila and Back Again] (in Czech). Říčany: Orego. ISBN 80-86117-61-8.

External links

- Official website

- František Sláma: Archive Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine: More on the History of the Czech Philharmonic between the 1940s and the 1980s

- Film of Czech Philharmonic in rehearsal on YouTube

- Václav Talich recording Dvořák's Slavonic Dances with the Czech Philharmonic in 1955 on YouTube, more about this recording Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine