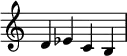

DSCH is a musical motif used by the composer Dmitri Shostakovich to represent himself. It is a musical cryptogram in the manner of the BACH motif, consisting of the notes D, E-flat, C, B natural, or in German musical notation D, Es, C, H (pronounced as "De-Es-Ce-Ha"), thus standing for the composer's initials in German transliteration: D. Sch. (Dmitri Schostakowitsch).

Usage

By Shostakovich

The motif occurs in many of his works, including:

- Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op. 77

- Fugue No. 15 in D-flat major, Op. 87 (only once, in the stretto)

- String Quartet No. 5 in B-flat major, Op. 92

- Symphony No. 10 in E minor, Op. 93

- String Quartet No. 6 in G major, Op. 101 (Played all at once by the four instruments at the end of each movement)

- String Quartet No. 8 in C minor, Op. 110 (appears in every single movement)

- Symphony No. 15 in A major, Op. 141.

- Piano Sonata No. 2 in B minor, Op. 61 (questionable)

By others

Many homages to Shostakovich (such as Schnittke's Prelude in memory of Dmitri Shostakovich or Tsintsadze's 9th String Quartet) make extensive use of the motif. The British composer Ronald Stevenson composed a large Passacaglia on it. Also Edison Denisov dedicated some works (1969 DSCH for clarinet, trombone, cello and piano, and his 1970 saxophone sonata) to Shostakovich, by quoting the motif several times and using it as the first four notes of a twelve-tone series. Denisov was Shostakovich's protégé for a long time.[1]

Sergei Prokofiev's Sinfonia Concertante, Op. 125 Symphony-Concerto (Prokofiev) contains the DSCH motif spelled at pitch in the second movement, measures 452-453, the point of maximum dissonance. Benjamin Britten's Rejoice in the Lamb (1943) contains the DSCH motif - but never at that pitch - repeated several times in the accompaniment, progressively getting louder each time, finally at fortissimo over the chords accompanying "And the watchman strikes me with his staff". The vocal text given to the motif is "silly fellow, silly fellow, is against me". A further reference appears in Britten's The Rape of Lucretia (1946), where the DSCH motif acts as the main structural component of Lucretia's aria "Give him this orchid."

The DSCH motif also appears in the orchestral accompaniment of Viola Concerto (Walton) - (1929) in bars 115-116 (up a minor 6th - 'B', 'C', 'A', 'G#') and in 122-123 (at the original pitch - 'D', 'Eb', 'C', 'B') of the First Movement (Andante Comodo) and, during the orchestral tutti before the Recapitulation of the same movement. This was never confirmed by William Walton (a contemporary of Shostakovich) himself, although he did refer to Dmitri Shostakovich as "the greatest composer of the 20th century".[2] Therefore, it is entirely possible that this was an intentional reference to the motif.

The contemporary Italian composer Lorenzo Ferrero made use of it in DEsCH, a composition for oboe, bassoon, piano and orchestra written in 2006 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Shostakovich's birth, and in Op.111 – Bagatella su Beethoven (2009), which blends themes from the Piano Sonata No. 32 in C minor, Op. 111 by Ludwig van Beethoven with the Shostakovich musical monogram.

The motif was also incorporated by Chumbawamba in "Hammer, Stirrup and Anvil" (2009), their song about Shostakovich's career under Stalin.

Danny Elfman, in his Russian influenced score for the 1995 film Dolores Claiborne, opened the film with the DSCH motif and, subsequently, used it throughout as a nod to Shostakovich's 8th String Quartet (which he cites on his Oct 10, 2006 Apple iTunes playlist as "Simply one of the most beautiful, exquisitely sad, and soulful pieces of music I've ever heard").

Tigran Hamasyan incorporated this motif in his song "Ara Resurrected", from his latest album The Call Within.

DSCH Journal, the standard journal of Shostakovich studies, takes its name from the motif. "DSCH" is sometimes used as an abbreviation of Shostakovich's name. DSCH Publishers Archived 2020-06-04 at the Wayback Machine is a Moscow publishing house that published the 150-volume New Collected Works of Dmitri Shostakovich in 2005, 25% of which contained previously unpublished works.

The motif is used by classical music comedians TwoSetViolin on their recent “Duh Duh Duh Dumm” music video. Shostakovich (played by Brett Yang ) appears, talking about his struggle against Soviet censorship. Shostakovich’s String Quartet No. 8 can be heard in the background.

Media

See also

References

- ↑ Taruskin, Richard (2010). Music in the Late Twentieth Century: The Oxford History of Western Music. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 463. ISBN 9780195384857.

- ↑ "British Composers in Interview" by R Murray Schafer (Faber 1960)

Bibliography

- Brown, Stephen C., “Tracing the Origins of Shostakovich’s Musical Motto,” Intégral 20 (2006): 69–103.

- Gasser, Mark. "Ronald Stevenson, Composer-Pianist: An Exegetical Critique from a Pianistic Perspective". PhD diss. [Western Australia]: Edith Cowan University, 2013.

External links

- "DSCH – Shostakovich's Motto", DSCH journal

- "DSCH Quotation Examples", DSCH journal