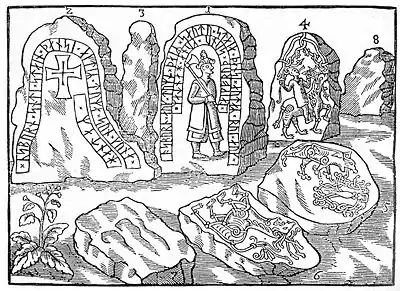

The Hunnestad Monument (Swedish: Hunnestadsmonumentet), listed as DR 282 through 286 in the Rundata catalog, was once located at Hunnestad at Marsvinsholm north-west of Ystad, Sweden. It was the largest and most famous of the Viking Age monuments in Scania, and in Denmark, only comparable to the Jelling stones. The monument was destroyed during the end of the 18th century by Eric Ruuth of Marsvinsholm, probably between 1782 and 1786 when the estate was undergoing sweeping modernization, though the monument survived long enough to be documented and depicted.

When the antiquary Ole Worm (1588–1654) explored the monument, it consisted of eight stones.[1] Five of them were image stones, and two of those image stones also had runic inscriptions. In the eighteenth century, all the stones were relocated or destroyed. Only three of the stones of the monument were recovered during the 19th century, and are today on display at the Kulturen museum in Lund. For a long time they were considered the only stones remaining, but on December 16, 2020 a fourth stone, DR 285 (number 6, in the picture), was discovered during excavations for a sewage line in Ystad municipality. Lying with its image facing up, it had been used in a bridge construction over the Hunnestad stream.[2]

Runestones

The first runestone (DR 282) was raised by Ásbjörn and Tumi in memory of Tumi's two brothers, whereas the last one (DR 283) was raised by Ásbjörn in memory of Tumi.

DR 282

The oldest of the two runestones depicts a large man dressed in a long coat and a pointed helmet. The man, who carries an axe on his right shoulder, is possibly a member of the Varangian Guard.

Latin transliteration:

- × osburn × (a)u(k) × tumi × þaiʀ × sautu × stain × þansi × a(f)[t]iʀ × rui × auk × ¶ laikfruþ × sunu × kuna × han[t]aʀ ×[3]

Old Norse transcription:

- Æsbiorn ok Tomi þeʀ sattu sten þænsi æftiʀ Roi ok Lekfrøþ, sunu Gunna Handaʀ.[3]

English translation:

- Ásbjôrn and Tumi they placed this stone in memory of Hróir and Leikfrøðr, Gunni Hand's sons.[3]

DR 283

The second runestone is decorated with a cross and was raised by Ásbjörn after Tumi.

Latin transliteration:

- × osburn × snti × stain × þansi × aftiʀ × tuma × sun × kuna × ¶ hantaʀ ×[4]

Old Norse transcription:

- Æsbiorn satti sten þænsi æftiʀ Toma, sun Gunna Handaʀ.[4]

English translation:

- Ásbjôrn placed this stone in memory of Tumi, Gunni Hand's son.[4]

Image stones DR 284 through DR 286

The three image stones, without any rune inscription, show three illustrations of a huge animal. One of them, DR 284 (Hunnestad 3), shows an animal ridden by a woman who has two snakes in her hands. She appears to be the wolf-riding giantess Hyrrokkin who helped the Æsir push Balder's ship into the sea during his funeral, and thus she would be an appropriate image for a funerary monument.[5] The wolf has a mane and pointed ears similar to the depiction of the wolf on the Tullstorp Runestone (DR 271) and the two wolves on the Lund 1 Runestone (DR 314).[6] The second image stone (the now lost DR 286), as depicted on Ole Worm's illustration, shows the animal beside a man's mask and the third image stone (the now found DR 285) shows the animal alone.

References

- 1 2 Ole, Worm (1643). Danicorum Monumentorum. Copenhagen. pp. 188–190. Archived from the original on 2011-07-19.

- ↑ "Sensationellt fynd från vikingatiden hittat vid grävning".

- 1 2 3 Project Samnordisk Runtextdatabas Svensk Archived 2011-08-07 at the Wayback Machine - Rundata entry for DR 282.

- 1 2 3 Project Samnordisk Runtextdatabas Svensk Archived 2011-08-07 at the Wayback Machine - Rundata entry for DR 283.

- ↑ Price, Neil (2006). "What's in a Name? An Archeological Identity Crisis for the Norse Gods (and Some of their Friends)". In Andrén, Anders; Jennbert, Kristina; et al. (eds.). Old Norse Religion in Long-Term Perspectives: Origins, Changes, and Interactions. Lund: Nordic Academic Press. p. 181. ISBN 91-89116-81-X.

- ↑ McKinnell, John (2005). Meeting the Other in Norse Myth and Legend. D. S. Brewer. p. 114. ISBN 1-84384-042-1.

Sources

- Djuret, an article in PDF format Archived 2009-09-14 at the Wayback Machine at the site of the Foteviken Museum, retrieved January 20, 2007.

- (in Swedish) Runstensmonument från 1000-talet, Hunnestad säteri och by i Ljunits härad i Malmöhus län.